Coal plant retirement presents a two-pronged problem: Utilities have to figure out how to replace lost power generation, and the surrounding community must reckon with the lost tax revenue and jobs from the power plants and the coal mines that supplied them.

From the beginning, Biden has

promised to help revitalize the economies of the communities left in coal’s wake. “We’re never going to forget the men and women who dug the coal and built the nation,” he said when he laid out his energy transition plan just a week after entering office. “We’re going to do right by them.”

Economic revitalization doesn’t happen overnight, of course, or even in the span of a four-year term. But money is already

rolling out in the form of targeted investments in new energy sources, businesses, and jobs in coal communities, and there’s more to come.

It’s the proactive planning aspect, however, that remains underresourced and scattershot.

Emily Grubert, a civil engineer and sociologist at the University of Notre Dame, told me there are few plants that are expected to make it past 2039 regardless, due to their age and the economics of operating them. The emissions rule’s real potential, then, is to bring about a more orderly — and potentially less painful — exit.

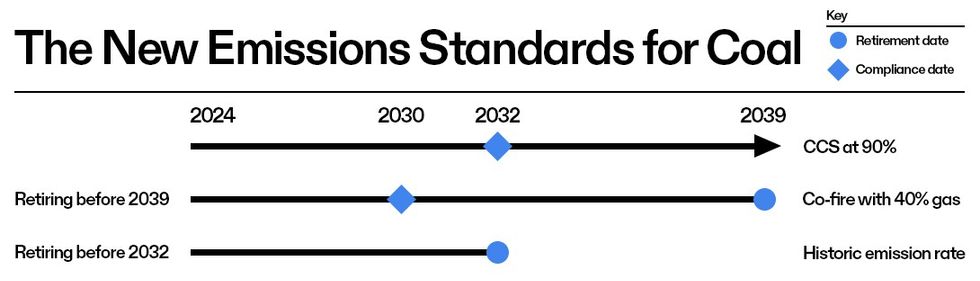

A Heatmap analysis of Energy Information Administration data found that of the nation’s roughly 230 remaining coal plants, 38 are scheduled to fully shut down by 2032. These plants won’t have to make any changes under the new rule. An additional five will shutter by 2039. These will be required to reduce their emissions in the interim, beginning in 2030, by replacing some of the coal they burn with natural gas. That leaves about 190 plants with either partial retirement plans or no plans at all that will be forced to make a decision between carbon capture and shutting down.

Grubert told me that many of these plants have, in fact, communicated informal plans to shut down that are not recorded in the federal data. That aside, she called it “amazing” how many have no retirement plans at all.

For surrounding communities, an impending coal transition can look really different in different places, depending on geography and how diverse the local economy is. Still, the first step should be the same everywhere. “What you need to do, really practically, is figure out what that plant is supporting,” Grubert told me. “What needs to be replaced, for whom, and by when?

It’s a lot more concrete than it seems: It’s some specific number of people, it’s some specific amount of tax revenue. It’s much easier to move forward once you actually know what those are.”

How much of that work has been done so far depends, in part, on the state. Some, like Colorado, New Mexico, and Illinois, have established new positions or entirely new offices dedicated to helping communities transition off fossil fuels. But other states, like Wyoming and Ohio, have advanced measures to keep coal plants open as long as possible.

Successful planning also depends on how clearly a retirement date is articulated and stuck to, Jeffrey Jacquet, an associate professor of rural sociology at Ohio State University who leads a multidisciplinary research project on coal communities there, told me. Some communities have been told one date and then been

blindsided when a plant has been forced to shut down years earlier for economic reasons. He noted one success story in Shadyside, Ohio, where the local school board was able to negotiate a deal to slowly step down its tax collections over four years after learning the RE Burger coal plant was going to close. “Had they not weaned us off losing that tax revenue, we would have been in terrible shape,” a school board administrator told a student on Jacquet’s project. “Fiscally we’re pretty good on solid ground now, but at one point it was an extremely bleak time.”

The new power plant rule could help address some of these problems by putting the entire country on the same set timeline, forcing plant operators to put retirement dates in writing. There’s still a risk some will fail early, in unforeseen ways, but at least communities will have been put on notice.

Those who go looking for help will find ample resources. When I started looking into all of the programs that exist to bring investment into coal communities, or otherwise help them diversify their economies, I was surprised at how much investment in coal communities had already been set in motion:

- The $750 million advanced manufacturing program under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law sent $50 million to a company called Boston Metal to build a factory producing critical minerals key to many clean energy technologies in Weirton, West Virginia, near the recently closed WH Sammis coal-fired power plant. It’s expected to create 200 jobs.

- The $1 billion Distressed Area Recompete Program from the CHIPS and Science Act named a group on the Crow Reservation in Montana as a finalist for a $20 million to $50 million grant for a new vocational training center and business incubator. The Crow Tribe is economically dependent on the Absaloka coal mine, and has been experiencing severe job and revenue loss as the mine’s revenue declines.

- The $9.7 billion Empowering Rural America Program included in the Inflation Reduction Act will give rural electric cooperatives — which include the most coal-dependent and cash-strapped utilities in the country — funding to purchase carbon-free electricity. The program was quickly oversubscribed, with applications totaling $46 billion.

This list is far from comprehensive. In fact, there are so many programs, it’s kind of a problem.

“So much of it comes down to the local capacity to take advantage of these opportunities,” Jacquet told me. “A lot of these communities are losing population, they’re facing out-migration. Community leaders are already overworked and overstressed.” (Possible case in point: I reached out to several local groups doing coal transition work in West Virginia and Kentucky for this story, and wasn’t able to get anyone on the phone.)

This isn’t a new problem, per se. The federal government had dozens of programs and pots of money set aside for rural economic development before the Biden administration came into the White House, but they were scattered across different agencies and departments within those agencies, making it difficult for any overworked, overstressed town manager to know where to start.

Jeremy Richardson, a manager of the carbon-free electricity program at the think tank RMI, told me he was involved in a group that pitched policies to the incoming president that would help ease the process. “It shouldn’t be on the community to navigate the entire federal bureaucracy to figure out what they qualify for,” he said.

Biden took the note. In his first climate executive order, he established the Interagency Working Group on Coal and Power Plant Communities and Economic Revitalization, which is building tools to help companies and local governments identify funding opportunities. Its “getting started guide,” which Richardson called a “fantastic piece of work,” walks communities and workers through 10 concrete steps, from identifying needs to developing a transition strategy to finding funding and implementing a project, with curated resources for each step. The group also established four “rapid response” teams to provide more targeted assistance to communities in areas with the highest loss of coal assets.

Jacquet summed up the group’s work as “hand holding,” stressing that it still required people at the local level that were willing and able to take advantage of these services. “I think we’re sort of seeing this phenomenon where the communities that are already best positioned to take advantage of these are going to be the ones that take advantage of it,” he said.

There are other limitations to the broader suite of federal assistance programs. For instance, even if a community is able to attract a big manufacturing project, there may be a several-years gap between the coal plant closing and the new job opportunities and local tax revenue manifesting.

That’s why the coordination efforts in states like Colorado, which was the first to establish an Office of Just Transition in 2019, are so promising. The office has a small staff of six, and a meager budget of $15 million, but is making progress by focusing on highly targeted assistance. In the town of Craig, two nearby coal-fired power plants are scheduled to retire over the next four years and four coal mines will shutter by 2030, taking with them 900 jobs and about 45% of the county’s tax revenue. A new “transition navigator” hired in January will help match the town’s needs with federal and state funding opportunities and serve as a central point of contact for coal workers and their families seeking connection to services.

“I think it’s been really helpful,” said Richardson. “They’ve had long conversations — several years of conversations — with those communities in northwest Colorado that are facing closures soon.” The office was controversial at first. Republicans called it “Orwellian” and unanimously opposed it. But in the years since, some of its staunchest critics have become its

biggest champions. “To me that says that they’re doing some good work and they’re making some inroads.”

There’s progress on the energy side, too. RMI is pushing a model called “clean repowering,” enabled by a suite of IRA incentives that offer tax credits and loan guarantees for clean energy projects in fossil fuel communities. The idea is that renewable energy projects can get around the yearslong bottleneck of connecting to the grid by building in close proximity to existing fossil fuel plants. A lot of these plants have “spare” interconnection rights that a solar or wind farm could use to connect a lot sooner.

RMI found 250 gigawatts of spare rights available — which is more than the capacity of the entire existing coal fleet. “If you can build a renewable facility alongside where that fossil plant is, maybe you use the fossil plant a little less because it’s cheaper to generate from the renewables, but you know, you don’t have to close it immediately,” said Richardson.

As Daniel Raimi, a senior research associate at Resources for the Future, told me, even though the coal transition has been in motion for decades, it’s still early. There hasn’t been enough research. Much of the funding and programs are new. No one really knows yet what’s working, or what could work better.

The only thing that’s clear, he said, is that if these communities are going to develop alternative economic futures, they really need to begin that process now.

People walk along an flooded highway on April 18, 2024 in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Photo by Francois Nel/Getty Images

People walk along an flooded highway on April 18, 2024 in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Photo by Francois Nel/Getty Images