AM Briefing

Headwinds Blowing

On Tesla’s sunny picture, Chinese nuclear, and Bad Bunny’s electric halftime show

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

On Tesla’s sunny picture, Chinese nuclear, and Bad Bunny’s electric halftime show

These are the 10 most important clean energy transition projects struggling to get off the ground

Rob talks with the lawmaker from New Mexico (and one-time mechanical engineer) about the present and future of climate policy.

And it’s blocking America’s economic growth, argues a former White House climate advisor.

On the FREEDOM Act, Siemens’ bet, and space data centers

Current conditions: After a brief reprieve of temperatures hovering around freezing, the Northeast is bracing for a return to Arctic air and potential snow squalls at the end of the week • Cyclone Fytia’s death toll more than doubled to seven people in Madagascar as flooding continues • Temperatures in Mongolia are plunging below 0 degrees Fahrenheit for the rest of the workweek.

Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum suggested the Supreme Court could step in to overturn the Trump administration’s unbroken string of losses in all five cases where offshore wind developers challenged its attempts to halt construction on turbines. “I believe President Trump wants to kill the wind industry in America,” Fox Business News host Stuart Varney asked during Burgum’s appearance on Tuesday morning. “How are you going to do that when the courts are blocking it?” Burgum dismissed the rulings by what he called “court judges” who “were all at the district level,” and said “there’s always the possibility to keep moving that up through the chain.” Burgum — who, as my colleague Robinson Meyer noted last month, has been thrust into an ideological crisis over Trump’s actions toward Greenland — went on to reiterate the claims made in a Department of Defense report in December that sought to justify the halt to all construction on offshore turbines on the grounds that their operation could “create radar interference that could represent a tremendous threat off our highly populated northeast coast.” The issue isn’t new. The Obama administration put together a task force in 2011 to examine the problem of “radar clutter” from wind turbines. The Department of Energy found that there were ways to mitigate the issue, and promoted the development of next-generation radar that could see past turbines.

The Trump administration, meanwhile, is facing accusations of violating the Constitution with its orders to keep coal-fired power stations operating past planned retirement. By mandating their coal plants stay open, two electrical cooperatives in Colorado said the Energy Department’s directive “constitutes both a physical taking and a regulatory taking” of property by the government without just compensation or due process, Utility Dive reported.

Back in December, the promise of a bipartisan deal on permitting reform seemed possible as the SPEED Act came up for a vote in the House. At the last minute, however, far-right Republicans and opponents of offshore wind leveraged their votes to win an amendment specifically allowing President Donald Trump to continue his attempts to kill off the projects to build turbines off the Eastern Seaboard. With key Democrats in the Senate telling Heatmap’s Jael Holzman that their support hinged on legislation that did the opposite of that, the SPEED Act stalled out. Now a new bipartisan bill aims to rectify what went wrong. The FREEDOM Act — an acronym for “Fighting for Reliable Energy and Ending Doubt for Open Markets” — would prevent a Republican administration from yanking permits from offshore wind or a Democratic one from going after already-licensed oil and gas projects, while setting new deadlines for agencies to speed up application reviews. I got an advanced copy of the bill Monday night, so you can read the full piece on it here on Heatmap.

One element I didn’t touch on in my story is what the legislation would do for geothermal. Next-generation geothermal giant Fervo Energy pulled off its breakthrough in using fracking technology to harness the Earth’s heat in more places than ever before just after the Biden administration completed work on its landmark clean energy bills. As a result, geothermal lost out on key policy boosts that, for example, the next-generation nuclear industry received. The FREEDOM Act would require the government to hold twice as many lease sales on federal lands for geothermal projects. It would also extend the regulatory shortcuts the oil and gas industry enjoys to geothermal companies.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

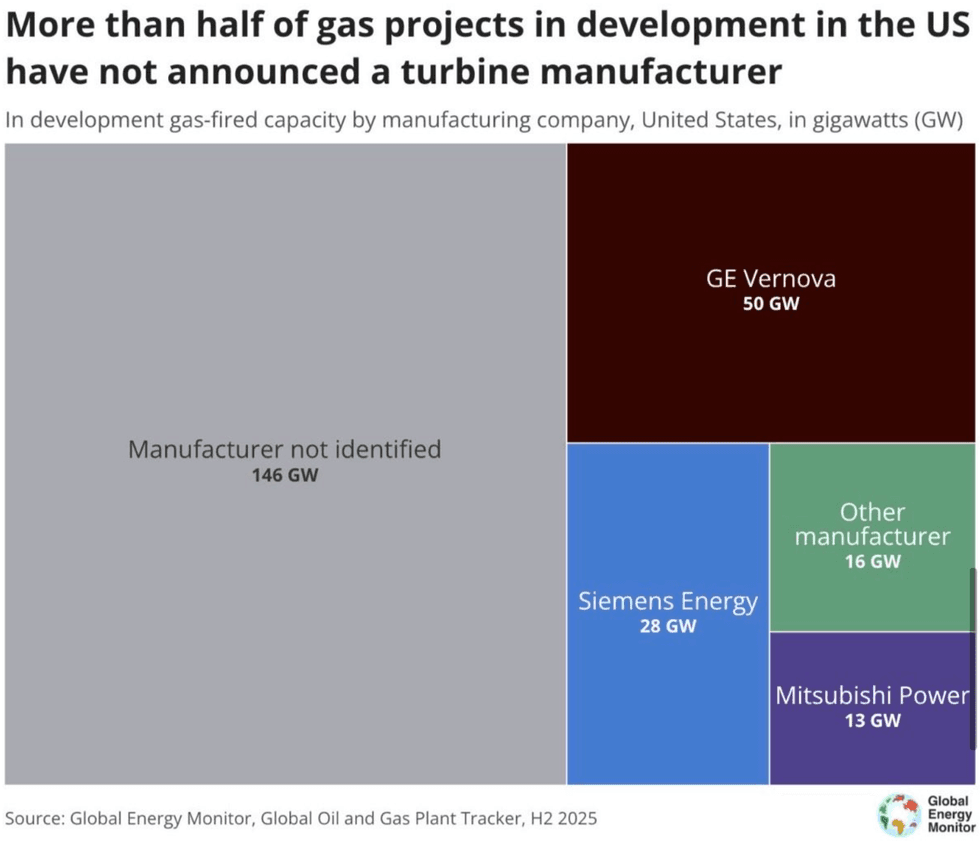

Take a look at the above chart. In the United States, new gas power plants are surging to meet soaring electricity demand. At last count, two thirds of projects currently underway haven’t publicly identified which manufacturer is making their gas turbines. With the backlog for turbines now stretching to the end of the decade, Siemens Energy wants to grow its share of booming demand. The German company, which already boasts the second-largest order book in the U.S. market, is investing $1 billion to produce more turbines and grid equipment. “The models need to be trained,” Christian Bruch, the chief executive of Siemens Energy, told The New York Times. “The electricity need is going to be there.”

While most of the spending is set to go through existing plants in Florida and North Carolina, Siemens Energy plans to build a new factory in Mississippi to produce electric switchgear, the equipment that manages power flows on the grid. It’s hardly alone. In September, Mitsubishi announced plans to double its manufacturing capacity for gas turbines over the next two years. After the announcement, the Japanese company’s share price surged. Until then, investors’ willingness to fund manufacturing expansions seemed limited. As Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin put it, “Wall Street has been happy to see developers get in line for whatever turbines can be made from the industry’s existing facilities. But what happens when the pressure to build doesn’t come from customers but from competitors?” Siemens just gave its answer.

At his annual budget address in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro touted Amazon’s plans to invest $20 billion into building two data center campuses in his state. But he said it’s time for the state to become “selective about the projects that get built here.” To narrow the criteria, he said developers “must bring their own power generation online or fully fund new generation to meet their needs — without driving up costs for homeowners or businesses.” He insisted that data centers conserve more water. “I know Pennsylvanians have real concerns about these data centers and the impact they could have on our communities, our utility bills, and our environment,” he said, according to WHYY. “And so do I.” The Democrat, who is running for reelection, also called on utilities to find ways to slash electricity rates by 20%.

For the first time, every vehicle on Consumer Reports’ list of top picks for the year is a hybrid (or available as one) or an electric vehicle. The magazine cautioned that its endorsement extended to every version of the winning vehicles in each category. “For example, our pick of the Honda Civic means we think the gas-only Civic, the hybrid, and the sporty Si are all excellent. But for some models, we emphasize the version that we think will work best for most people.” But the publication said “the hybrid option is often quieter and more refined at speed, and its improved fuel efficiency usually saves you money in the long term.”

Elon Musk wants to put data centers in space. In an application to the Federal Communications Commission, SpaceX laid out plans to launch a constellation of a million solar-powered data centers to ease the strain the artificial intelligence boom is placing on the Earth’s grids. Each data center, according to E&E News, would be 31 miles long and operate more than 310 miles above the planet’s surface. “By harnessing the Sun’s abundant, clean energy in orbit — cutting emissions, minimizing land disruption, and reducing the overall environmental costs of grid expansion — SpaceX’s proposed system will enable sustainable AI advancement,” the company said in the filing.

The FREEDOM Act aims to protect energy developments from changing political winds.

A specter is haunting permitting reform talks — the specter of regulatory uncertainty. That seemingly anodyne two-word term has become Beltway shorthand for President Donald Trump’s unrelenting campaign to rescind federal permits for offshore wind projects. The repeated failure of the administration’s anti-wind policies to hold up in court aside, the precedent the president is setting has spooked oil and gas executives, who warn that a future Democratic government could try to yank back fossil fuel projects’ permits.

A new bipartisan bill set to be introduced in the House Tuesday morning seeks to curb the executive branch’s power to claw back previously-granted permits, protecting energy projects of all kinds from whiplash every time the political winds change.

Dubbed the FREEDOM Act, the legislation — a copy of which Heatmap obtained exclusively — is the latest attempt by Congress to speed up construction of major energy and mining projects as the United States’ electricity demand rapidly eclipses new supply and Chinese export controls send the price of key critical minerals skyrocketing.

Two California Democrats, Representatives Josh Harder and Adam Gray, joined three Republicans, Representatives Mike Lawler of New York, Don Bacon of Nebraska, and Chuck Edwards of North Carolina, to sponsor the bill.

While green groups have criticized past proposals to reform federal permitting as a way to further entrench fossil fuels by allowing oil and gas to qualify for the new shortcuts, Harder pitched the bill as relief to ratepayers who “are facing soaring energy prices because we’ve made it too hard to build new energy projects.”

“The FREEDOM Act delivers the smart, pro-growth certainty that critical energy projects desperately need by cutting delays, fast-tracking approvals, and holding federal agencies accountable,” he told me in a statement. “This is a common sense solution that will mean more energy projects being brought online in the short term and lower energy costs for our families for the long run.”

The most significant clause in the 77-page proposal lands on page 59. The legislation prohibits federal agencies and officials from issuing “any order or directive terminating the construction or operation of a fully permitted project, revoke any permit or authorization for a fully permitted project, or take any other action to halt, suspend, delay, or terminate an authorized activity carried out to support a fully permitted project.”

There are, of course, exceptions. Permits could still be pulled if a project poses “a clear, immediate, and substantiated harm for which the federal order, directive, or action is required to prevent, mitigate, or repair.” But there must be “no other viable alternative.”

Such a law on the books would not have prevented the Trump administration from de-designating millions of acres of federal waters to offshore wind development, to pick just one example. But the legislation would explicitly bar Trump’s various attempts to halt individual projects with stop work orders. Even the sweeping order the Department of the Interior issued in December that tried to stop work on all offshore wind turbines currently under construction on the grounds of national security would have needed to prove that the administration exhausted all other avenues first before taking such a step.

Had the administration attempted something similar anyway, the legislation has a mechanism to compensate companies for the costs racked up by delays. The so-called De-Risking Compensation Fund, which the bill would establish at the Treasury Department, would kick in if the government revoked a permit, canceled a project, failed to meet deadlines set out in the law for timely responses to applications, or ran out the clock on a project such that it’s rendered commercially unviable.

The maximum payout is equal to the company’s capital contribution, with a $5 million minimum threshold, according to a fact-sheet summarizing the bill for other lawmakers who might consider joining as co-sponsors. “Claims cannot be denied based on project permits or energy technology type,” the document reads. A company that would have benefited from a payout, for example, would be TC Energy, the developer behind the Keystone XL oil pipeline the Biden administration canceled shortly after taking office.

Like other permitting reform legislation, the FREEDOM Act sets new rules to keep applications moving through the federal bureaucracy. Specifically, it gives courts the right to decide whether agencies that miss deadlines should have to pay for companies to hire qualified contractors to complete review work.

The FREEDOM Act also learned an important lesson from the SPEED Act, another bipartisan bill to overhaul federal permitting that passed the House in December but has since become mired in the Senate. The SPEED Act lost Democratic support — ultimately passing the House with just 11 Democratic votes — after far-right Republicans and opponents of offshore wind leveraged a special carveout to continue allowing the administration to commence its attacks on seaborne turbine projects.

The amendment was a poison pill. In the Senate, a trio of key Democrats pushing for permitting reform, Senate Energy and Natural Resources ranking member Martin Heinrich, Environment and Public Works ranking member Sheldon Whitehouse, and Hawaii senator Brian Schatz, previously told Heatmap’s Jael Holzman that their support hinged on curbing Trump’s offshore wind blitz.

Those Senate Democrats “have made it clear that they expect protections against permitting abuses as part of this deal — the FREEDOM Act looks to provide that protection,” Thomas Hochman, the director of energy and infrastructure policy at the Foundation for American Innovation, told me. A go-to policy expert on clearing permitting blockages for energy projects, Hochman and his center-right think tank have been in talks with the lawmakers who drafted the bill.

A handful of clean-energy trade groups I contacted did not get back to me before publication time. But American Clean Power, one of the industry’s dominant associations, withdrew its support for the SPEED Act after Republicans won their carveout. The FREEDOM Act would solve for that objection.

The proponents of the FREEDOM Act aim for the bill to restart the debate and potentially merge with parts of the previous legislation.

“The FREEDOM Act has all the critical elements you’d hope to see in a permitting certainty bill,” Hochman said. “It’s tech-neutral, it covers both fully permitted projects and projects still in the pipeline, and it provides for monetary compensation to help cover losses for developers who have been subject to permitting abuses.”