AM Briefing

Trump’s Reactor Realism

On the solar siege, New York’s climate law, and radioactive data center

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

On the solar siege, New York’s climate law, and radioactive data center

On nuclear tax credits, BLM controversy, and a fusion maverick’s fundraise

That doesn’t mean it plans to produce electricity anytime soon.

On Cybertruck deaths, Texas wind waste, and American aluminum

The long-duration energy storage startup is scaling up fast, but as Form CEO Mateo Jaramillo told Heatmap, “There aren’t any shortcuts.”

On the California atom, Russian nuclear theft, and Taiwan’s geothermal hope

Current conditions: A blockbuster blizzard blanketed the Northeast in up to 2 feet of snow, trigger outages for nearly 500,000 households • Hot, dry Harmattan conditions are blowing into Nigeria out of the Sahara, leaving the capital, Abuja, and the largest city, Lagos, roasting in nearly 100 degrees Fahrenheit • Much of South Australia, the Northern Territory, and Victoria are bracing for severe thunderstorms and flooding.

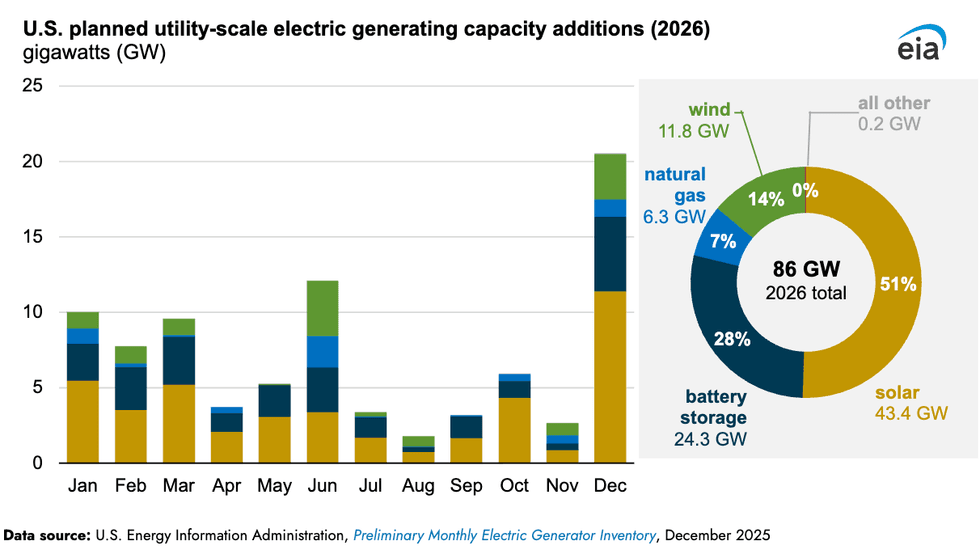

By the end of this year, U.S. developers are on pace to add 86 gigawatts of new utility-scale generating capacity to the American grid. Just 7% of that will come from natural gas. The other 93%? Solar, batteries, and wind, according to the latest inventory by the Energy Information Administration. Utility-scale solar projects alone will provide 51% of the new generating capacity, followed by batteries at 28%, and wind at 14%. Critics of renewables, such as Secretary of Energy Chris Wright, would point out that generating capacity does not equal generation, and that as has happened recently, gas, coal, and nuclear power may well end up pumping out a lot of the electricity this year. But rapid expansion of renewables and batteries comes largely despite the Trump administration’s efforts to curb the growth of what top officials dismiss as “unreliable” sources of power. Surging electricity demand from data centers has left gas turbines backordered; geothermal plants are still at an early stage; and new nuclear reactors are still years away. That makes solar and wind, already some of the cheapest sources to build, the only obvious options to bring new generation online as quickly as possible. In a sense, Trump may have helped nudge 2026’s boom into existence by phasing off federal tax credits for renewables this year, spurring a rush to get projects started and lock in the writeoffs.

That doesn’t mean the solar, battery, and wind sectors aren’t facing steep challenges. Just last week, Heatmap’s Jael Holzman rounded up four local fights on opposite coasts, including over a big solar farm in Oregon.

California could consider building anything from a large-scale Westinghouse AP1000 to a next-generation microreactor if a new bill to clarify the state’s ban on new nuclear power plants passes into law. On Friday, Assemblymember Lisa Calderon, a Democrat from Southern California, introduced AB2647 to modify the state moratorium put in place in 1976, three years before the Three Mile Island accident, to allow for construction of modern nuclear reactors. The legislation would exempt all reactor designs certified by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission after January 1, 2005. That clears the way for an AP1000, which was approved in 2006, and today is the only new design in commercial operation in the U.S., or any of the new small modular reactors and microreactors now racing to come to market. The bill is bringing together disparate factions in the California legislature. Progressive Assemblymember Alex Lee co-sponsored the legislation, while Senator Brian Jones, the highest ranking Republican in the state’s upper chamber, is backing a Senate version of the legislation.

Since Friday, I can report exclusively in this newsletter, the bill has two new supporters. Patrick Ahrens, a Silicon Valley-area Democrat, has signed on as a backer, and the Sheet Metal Workers union has said it would support the bill. “Pinching myself,” Ryan Pickering — a reactor developer and Berkeley-based activist who helped lead the successful campaign to cancel the closure of the state’s last plant, the Diablo Canyon nuclear station — responded when I texted him to ask about the bill. “California has an epic history in nuclear energy. We built 11 reactors across this state and once envisioned up to 14 gigawatts of nuclear electricity. This technology is part of our inheritance as Californians,” he said. “Assembly Bill 2647 gives California the opportunity to begin building nuclear energy again.”

If you have ever crossed the Queensboro Bridge from Manhattan’s 59th Street over to Long Island City in Queens, you have no doubt seen the Ravenswood Generating Station. The four candycane-colored smokestacks of New York City’s largest power plant, a more than 2-gigawatt facility equipped to burn both fuel oil and natural gas, rise on the lefthand side of the bridge, looming over the East River. Just a few years ago, its owner, LS Power, envisioned transforming the plant through a subsidiary called Rise Light and Power, which aimed to build a large-scale battery hub fed by new transmission lines connecting the facility to nearby offshore wind farms and onshore turbines upstate. Now, as Heatmap’s Emily Pontecorvo reported in a Friday scoop, the company is selling Ravenswood to the Texas energy giant NRG. It’s not yet clear what the sale means for the so-called Renewable Ravenswood plan, which Emily wrote was already “hanging by a thread.”

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

Since the start of its invasion of Ukraine, Russia has maintained clear designs on the Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant. Europe’s largest atomic generating station, located in an occupied province of eastern Ukraine, has been offline for the past four years. But, in a bid to shore up on the Kremlin’s desired war prizes as peace negotiations sputter, Russia’s nuclear regulator Rostekhnadzor has issued a 10-year operating license for Unit 2 of the plant. In its announcement, NucNet reported Friday, Rostekhnadzor said the move would open the door to building more Russian nuclear plants in the region. Rosatom, Moscow’s state-owned nuclear company, has submitted an application for an operating license for Unit 6, and aims to do the same for units 3, 4, and 5 by the end of this year.

The neighboring country most eager to contain Russia, meanwhile, took a big step toward building its first nuclear plant. The Supreme Administrative Court in Poland, whose debut facility is going with American technology, rejected an environmental complaint aimed at halting construction of AP1000 reactors at the site on the Baltic sea.

Earlier this month, I told you about Equinor’s plans to scale back its investments in carbon capture and sequestration, despite Norway’s world-leading progress on pumping captured CO2 back underground. Now the Norwegian energy giant is quitting on one of the European Union’s landmark projects to prove hydrogen fuel can be produced at scale using natural gas equipped with CCS. The company last week abandoned a gigawatt-sized blue hydrogen plant in the Netherlands as demand for the fuel stalls. Some may welcome the blue hydrogen recession. As Heatmap’s Katie Brigham wrote last year, a major blue hydrogen plant in Louisiana had been poised to add more emissions than it saved.

Things are looking sunnier in South America for green hydrogen, the carbon-free version of the fuel made from blasting freshwater with enough renewable electricity to separate out H from H2O. Colombia just completed a feasibility study on the country’s first industrial-scale green hydrogen project, set to generate 120,000 metric tons of green ammonia per year at a remarkably low price, according to Hydrogen Insight. At the opposite end of the continent, Uruguay’s 1.1-gigawatt green hydrogen-fueled methanol plant last week lined up a major offtaker that plans to buy the chemical to make lower-carbon gasoline. The purchaser? A fuel company based in a major artery of European trade, Germany’s Port of Hamburg.

Taiwan is in an energy crisis. The self-governing island, whose “silicon shield” against China is predicated on its capacity to manufacture enough energy-intensive semiconductors to be invaluable to the global economy, shut down its last nuclear reactor last year. By exiting atomic energy while struggling to build offshore wind turbines, the government in Taipei has rendered Taiwan almost entirely dependent on imported fuels. In an age when, as Russia has shown in Ukraine, blackouts are key weapons, the People’s Liberation Army need only make liquified natural gas dangerous to ship through the Taiwan Strait to cause blackouts. But geothermal power, development of which stalled out after the 1970s, offers a unique tool for Taiwan. Located on the Pacific Rim, the island has lots of hot rocks. Now it finally has a growing geothermal industry again, too. The CPC Corporation Taiwan said just before Lunar New Year started last week that it had just started generating power from the 5.4-megawatt Yilan Tuchang Geothermal plant. While small, it’s now the largest geothermal plant in Taiwan.

Heron Power and DG Matrix each score big funding rounds, plus news for heat pumps and sustainable fashion.

While industries with major administrative tailwinds such as nuclear and geothermal have been hogging the funding headlines lately, this week brings some variety with news featuring the unassuming but ever-powerful transformer. Two solid-state transformer startups just announced back-to-back funding rounds, promising to bring greater efficiency and smarter services to the grid and data centers alike. Throw in capital supporting heat pump adoption and a new fund for sustainable fashion, and it looks like a week for celebrating some of the quieter climate tech solutions.

Transformers are the silent workhorses of the energy transition. These often-underappreciated devices step up voltage for long-distance electricity transmission and step it back down so that it can be safely delivered to homes and businesses. As electrification accelerates and data centers race to come online, demand for transformers has surged — more than doubling since 2019 — creating a supply crunch in the U.S. that’s slowing the deployment of clean energy projects.

Against this backdrop, startup Heron Power just raised a $140 million Series B round co-led by Andreessen Horowitz and Breakthrough Energy Ventures to build next-generation solid state transformers. The company said its tech will be able to replace or consolidate much of today’s bulky transformer infrastructure, enabling electricity to move more efficiently between low-voltage technologies like solar, batteries, and data centers and medium-voltage grids. Heron’s transformers also promise greater control than conventional equipment, using power electronics and software to actively manage electricity flows, whereas traditional transformers are largely passive devices designed to change voltage.

This new funding will allow Heron to build a U.S.manufacturing facility designed to produce around 40 gigawatts of transformer equipment annually; it expects to begin production there next year. This latest raise follows quickly on the heels of its $38 million Series A round last May, reflecting hunger among customers for more efficient and quicker to deploy grid infrastructure solutions. Early announced customers include the clean energy developer Intersect Power and the data center developer Crusoe.

It’s a good time to be a transformer startup. DG Matrix, which also develops solid-state transformers, closed a $60 million Series A this week, led by Engine Ventures. The company plans to use the funding to scale its manufacturing and supply chain as it looks to supply data centers with its power-conversion systems.

Solid-state transformers — which use semiconductors to convert and control electricity — have been in the research and development phase for decades. Now they’re finally reaching the stage of technical maturity needed for commercial deployment, driving a surge in activity across the industry. DG Matrix’s emphasis is on creating flexible power conversion solutions, marketing its product as the world’s first “multi-port” solid-state transformer capable of managing and balancing electricity from multiple different sources at once.

“This Series A marks our transition from breakthrough technology to scaled infrastructure deployment,” Haroon Inam, DG Matrix’s CEO, said in a statement. “We are working with hyperscalers, energy companies, and industrial customers across North America and globally, with multiple gigawatt-class datacenters in the pipeline.” According to TechCrunch, data centers make up roughly 90% of DG Matrix’s current customer base, as its transformers can significantly reduce the space data centers require for power conversion.

Zero Homes, a digital platform and marketplace that helps homeowners manage the heat pump installation process, just announced a $16.8 million Series A round led by climate tech investor Prelude Ventures. The company’s free smartphone app lets customers create a “digital twin” of their home — a virtual model that mirrors the real-world version, built from photos, videos, and utility data. This allows homeowners to get quotes, purchase, and plan for their HVAC upgrade without the need for a traditional in-person inspection. The company says this will cut overall project costs by 20% on average.

Zero works with a network of vetted independent installers across the U.S., with active projects in California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Illinois. As the startup plans for national expansion, it’s already gained traction with some local governments, partnering with Chicago on its Green Homes initiative and netting $745,000 from Colorado’s Office of Economic Development to grow its operations in Denver.

Climactic, an early-stage climate tech VC, launched a new hybrid fund called Material Scale, aimed at helping sustainable materials and apparel startups navigate the so-called “valley of death” — the gap between early-stage funding and the later-stage capital needed to commercialize. As Climactic’s cofounder Josh Fesler explained on LinkedIn, the fund is designed to cover the extra costs involved with sustainable production, bridging the gap between the market price of conventional materials and the higher price of sustainable materials.

Structured as a “hybrid debt-equity platform,” the fund allows Climactic’s investors to either take a traditional equity stake in materials startups or provide them with capital in the form of loans. TechCrunch reports that the fund’s initial investments will come from an $11 million special purpose vehicle, a separate entity created to fund a small set of initial investments that sits outside Material Scale’s main investing pool.

The fashion industry accounts for roughly 10% of global emissions. “These days there are many alt materials startups that have moved through science and structural risk, have venture funding, credible supply chains and most importantly can achieve market price and positive gross margins just with scale,” Fesler wrote in his LinkedIn post. “They just need the capital to grow into their rightful commercial place.”