Lifestyle

The Quest to Ban the Best Raincoats in the World

Why Patagonia, REI, and just about every other gear retailer are going PFAS-free.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Why Patagonia, REI, and just about every other gear retailer are going PFAS-free.

On the solar siege, New York’s climate law, and radioactive data center

On nuclear tax credits, BLM controversy, and a fusion maverick’s fundraise

On Cybertruck deaths, Texas wind waste, and American aluminum

On the California atom, Russian nuclear theft, and Taiwan’s geothermal hope

On geothermal’s heat, Exxon Mobil’s CCS push, and Maine’s solar

Current conditions: More than a foot of snow is blanketing the California mountains • With thousands already displaced by flooding, Papua New Guinea is facing more days of thunderstorms ahead • It’s snowing in Ulaanbaatar today, and temperatures in the Mongolian capital will plunge from 31 degrees Fahrenheit to as low as 2 degrees by Sunday.

We all know the truisms of market logic 101. Precious metals surge when political volatility threatens economic instability. Gun stocks pop when a mass shooting stirs calls for firearm restrictions. And — as anyone who’s been paying attention to the world over the past year knows — oil prices spike when war with Iran looks imminent. Sure enough, the price of crude hit a six-month high Wednesday before inching upward still on Thursday after President Donald Trump publicly gave Tehran 10 to 15 days to agree to a peace deal or face “bad things.” Despite the largest U.S. troop buildup in the Middle East since 2003, the American military action won’t feature a ground invasion, said Gregory Brew, the Eurasia Group analyst who tracks Iran and energy issues. “It will be air strikes, possibly commando raids,” he wrote Thursday in a series of posts on X. Comparisons to Iraq “miss the mark,” he said, because whatever Trump does will likely wrap up in days. The bigger issue is that the conflict likely won’t resolve any of the issues that make Iran such a flashpoint. “There will be no deal, the regime will still be there, the missile and nuclear programs will remain and will be slowly rebuilt,” Brew wrote. “In six months, we could be back in the same situation.”

California, Colorado, and Washington led 10 other states in suing the Trump administration this week over the Department of Energy’s termination of billions in federal funding for clean energy and infrastructure projects. In a lawsuit filed in federal court in San Francisco, the states accuse the agency of using a “nebulous and opaque” review process to justify slashing billions in funding that was already awarded. “These aren’t optional programs — these are investments approved by bipartisan majorities in Congress,” California Attorney General Rob Bonta said at a press conference announcing the lawsuit, according to Courthouse News Service. “The president doesn’t get to cancel them simply because he disagrees with them. California won’t allow President Trump and his administration to play politics with our economy, our energy grid and our jobs.”

Get Heatmap AM directly in your inbox every morning:

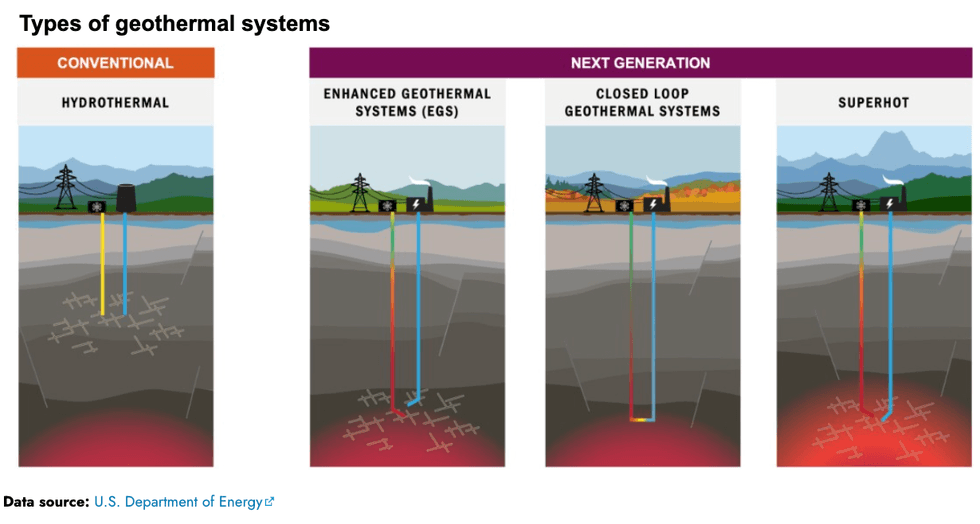

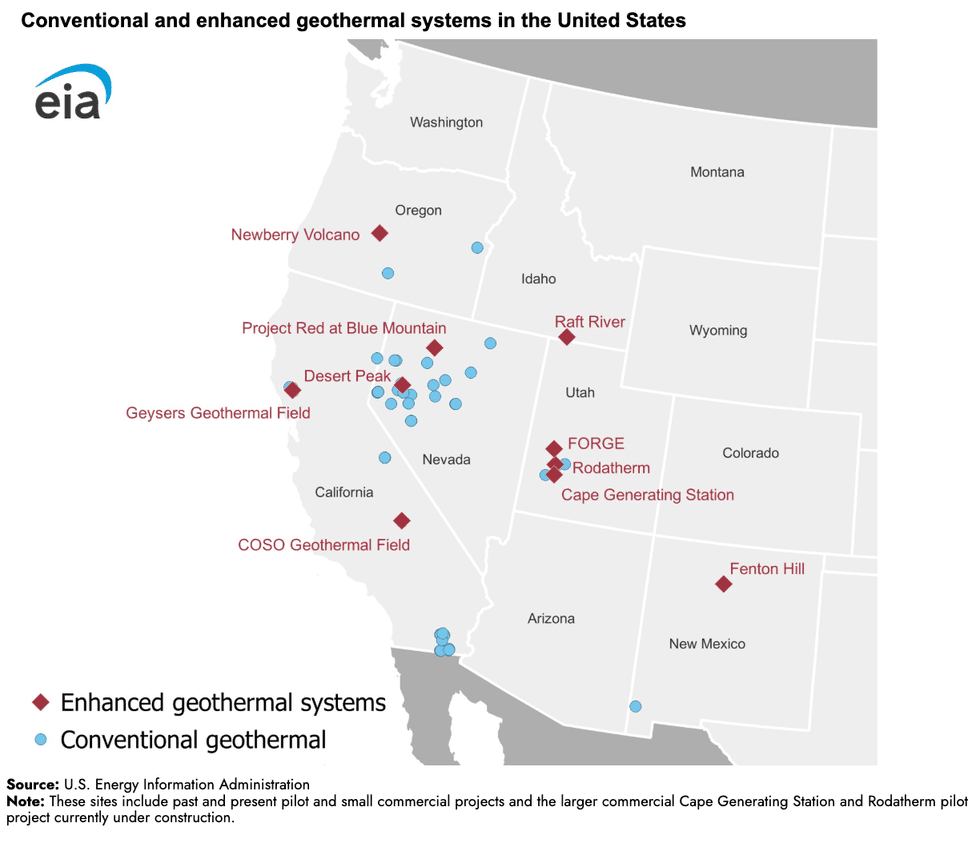

If you’re looking for a sign of the coming geothermal energy boom in the U.S., consider this: There is now a double-digit number of next-generation projects underway, according to an overview the Energy Information Administration published Thursday. For the past century, geothermal energy has relied upon finding and tapping into suitably hot underground reservoirs of water. But a new generation of “enhanced” geothermal companies is using modern drilling techniques to harness heat from dry rocks.

If you’re looking for a thorough overview of the technology, Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote the definitive 101 explainer here. But a few represent some of the earliest experiments in enhanced geothermal, including the Fenton Hill in New Mexico, established in the 1970s, which was the world’s first successful project to use the technology.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

When Exxon Mobil announced plans in December to scale back its spending on low-carbon investments, the oil giant justified the move in part on all the carbon capture and storage projects poised to come online this year that would vault the company ahead of its rivals. This week, Exxon Mobil started transporting and storing captured carbon dioxide at its latest facility in Louisiana. The New Generation Gas Gathering facility on the western edge of the state’s Gulf Coast is the company’s second CCS project in Louisiana. Known as NG3, the project is set to remove 1.2 million tons of CO2 per year from gas streams headed to export markets on the coast. The Carbon Herald reported that two additional CCS projects are set to start up operations this year.

CCS got a big boost in October when Google agreed to back construction of a gas-fired power plant built with carbon capture tech from the ground up. The plant, which Matthew noted at the time would be the first of its kind at a commercial scale, is sited near a well where captured carbon can be injected. Senate Democrats, meanwhile, are reportedly probing the Trump administration’s decision to redirect CCS funding to coal plants.

In 2019, Maine expanded its Net Energy Billing program to subsidize construction of commercial-scale solar farms across the state. “And it worked,” Maine Public Radio reported last July when the state passed a law to phase out the funding, “too well, some argue.” In 2025 alone, ratepayers in the state were on the hook for $234 million to support the program. Solar companies sued, arguing that the abrupt cut to state support had unfairly deprived them of funding. But this week U.S. District Judge Stacey Neumann denied a motion the owners of dozens of solar farms filed requesting an injunction.

That isn’t to say things aren’t looking sunny for solar in Maine. On the contrary, just yesterday the developer Swift Current Energy secured $248 million in project financing for a 122-megawatt solar farm and the Poland Spring water company went on statewide TV to show off the new panels on its bottling plant. The federal outlook isn’t as bright at the moment. As Heatmap’s Jael Holzman reported in December, the solar industry was begging Congress for help to end the Trump administration’s permitting blockade on new projects on federal lands.

The Trump-stumping country music star John Rich is continuing his crusade against the Tennessee Valley Authority. Months after blocking construction of a gas plant in his neighborhood, Rich personally pressed TVA CEO Don Moul to reroute a transmission line, posting a video Thursday of farmers who opposed the federal utility’s use of the right of way process to push through the project. Rich said Moul “personally told me as of this morning” TVA will put the effort on hold. The left-wing energy writer and Heatmap contributor Fred Stafford summed it up this way on X: “MAGA NIMBY rises, Dark Abundance falls. TVA ratepayers will be paying more for a rerouted transmission project because this country music star threw his support behind a local farmer who refuses to allow the transmission line to cross his land.”

On the real copper gap, Illinois’ atomic mojo, and offshore headwinds

Current conditions: The deadliest avalanche in modern California history killed at least eight skiers near Lake Tahoe • Strong winds are raising the wildfire risk across vast swaths of the northern Plains, from Montana to the Dakotas, and the Southwest, especially New Mexico, Texas, and Oklahoma • Nairobi is bracing for days more of rain as the Kenyan capital battles severe flooding.

Last week, the Environmental Protection Agency repealed the “endangerment finding” that undergirds all federal greenhouse gas regulations, effectively eliminating the justification for curbs on carbon dioxide from tailpipes or smokestacks. That was great news for the nation’s shrinking fleet of coal-fired power plants. Now there’s even more help on the way from the Trump administration. The agency plans to curb rules on how much hazard pollutants, including mercury, coal plants are allowed to emit, The New York Times reported Wednesday, citing leaked internal documents. Senior EPA officials are reportedly expected to announce the regulatory change during a trip to Louisville, Kentucky on Friday. While coal plant owners will no doubt welcome less restrictive regulations, the effort may not do much to keep some of the nation’s dirtiest stations running. Despite the Trump administration’s orders to keep coal generators open past retirement, as Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote in November, the plants keep breaking down.

At the same time, the blowback to the so-called climate killshot the EPA took by rescinding the endangerment finding has just begun. Environmental groups just filed a lawsuit challenging the agency’s interpretation of the Clean Air Act to cover only the effects of regional pollution, not global emissions, according to Landmark, a newsletter tracking climate litigation.

Copper prices — as readers of this newsletter are surely well aware — are booming as demand for the metal needed for virtually every electrical application skyrockets. Just last month, Amazon inked a deal with Rio Tinto to buy America’s first new copper output for its data center buildout. But new research from a leading mineral supply chain analyst suggests the U.S. can meet 145% of its annual demand using raw copper from overseas and domestic mines and from scrap. By contrast, China — the world’s largest consumer — can source just 40% of its copper that way. What the U.S. lacks, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, is the downstream processing capacity to turn raw copper into the copper cathode manufacturers need. “The U.S. is producing more copper than it uses, and is far more self-reliant than China in terms of raw materials,” Benchmark analyst Albert Mackenzie told the Financial Times. The research calls into question the Trump administration’s mineral policy, which includes stockpiling copper from jointly-owned ventures in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and domestically. “Stockpiling metal ores doesn’t help if you don’t have midstream processing,” Stephen Empedocles, chief executive of US lobbying firm Clark Street Associates, told the newspaper.

Illinois generates more of its power from nuclear energy than any other state. Yet for years the state has banned construction of new reactors. Governor JB Pritzker, a Democrat, partially lifted the prohibition in 2023, allowing for development of as-yet-nonexistent small modular reactors. With excitement about deploying large reactors with time-tested designs now building, Pritzker last month signed legislation fully repealing the ban. In his state of the state address on Wednesday, the governor listed the expansion of atomic energy among his administration’s top priorities. “Illinois is already No. 1 in clean nuclear energy production,” he said. “That is a leadership mantle that we must hold onto.” Shortly afterward, he issued an executive order directing state agencies to help speed up siting and construction of new reactors. Asked what he thought of the governor’s move, Emmet Penney, a native Chicagoan and nuclear expert at the right-leaning Foundation for American Innovation, told me the state’s nuclear lead is “an advantage that Pritzker wisely wants to maintain.” He pointed out that the policy change seems to be copying New York Governor Kathy Hochul’s playbook. “The governor’s nuclear leadership in the Land of Lincoln — first repealing the moratorium and now this Hochul-inspired executive order — signal that the nuclear renaissance is a new bipartisan commitment.”

The U.S. is even taking an interest in building nuclear reactors in the nation that, until 1946, was the nascent American empire’s largest overseas territory. The Philippines built an American-made nuclear reactor in the 1980s, but abandoned the single-reactor project on the Bataan peninsula after the Chernobyl accident and the fall of the Ferdinand Marcos dictatorship that considered the plant a key state project. For years now, there’s been a growing push in Manila to meet the country’s soaring electricity needs by restarting work on the plant or building new reactors. But Washington has largely ignored those efforts, even as the Russians, Canadians, and Koreans eyed taking on the project. Now the Trump administration is lending its hand for deploying small modular reactors. The U.S. Trade and Development Agency just announced funding to help the utility MGEN conduct a technical review of U.S. SMR designs, NucNet reported Wednesday.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

Despite the American government’s crusade against the sector, Europe is going all in on offshore wind. For a glimpse of what an industry not thrust into legal turmoil by the federal government looks like, consider that just on Wednesday the homepage of the trade publication OffshoreWIND.biz featured stories about major advancements on at least three projects totaling nearly 5 gigawatts:

That’s not to say everything is — forgive me — breezy for the industry. Germany currently gives renewables priority when connecting to the grid, but a new draft law would give grid operators more discretion when it comes to offshore wind, according to a leaked document seen by Windpower Monthly.

American clean energy manufacturing is in retreat as the Trump administration’s attacks on consumer incentives have forced companies to reorient their strategies. But there is at least one company setting up its factories in the U.S. The sodium-ion battery startup Syntropic Power announced plans to build 2 gigawatts of storage projects in 2026. While the North Carolina-based company “does not reveal where it manufactures its battery systems,” Solar Power World reported, it “does say” it’s establishing manufacturing capacity in the U.S. “We’re making this move now because the U.S. market needs storage that can be deployed with confidence, supported by certification, insurance acceptance, and a secure domestic supply chain,” said Phillip Martin, Syntropic’s chief executive.

For years now, U.S. manufacturers have touted sodium-ion batteries as the next big thing, given that the minerals needed to store energy are more abundant and don’t afford China the same supply-chain advantage that lithium-ion packs do. But as my colleague Katie Brigham covered last April, it’s been difficult building a business around dethroning lithium. New entrants are trying proprietary chemistries to avoid the mistakes other companies made, as Katie wrote in October when the startup Alsym launched a new stationary battery product.

Last spring, Heron Power, the next-generation transformer manufacturer led by a former Tesla executive, raised $38 million in a Series A round. Weeks later, Spain’s entire grid collapsed from voltage fluctuations spurred by a shortage of thermal power and not enough inverters to handle the country’s vast output of solar power — the exact kind of problem Heron Power’s equipment is meant to solve. That real-life evidence, coupled with the general boom in electrical equipment, has clearly helped the sales pitch. On Wednesday, the company closed a $140 million Series B round co-led by the venture giants Andreessen Horowitz and Breakthrough Energy Ventures. “We need new, more capable solutions to keep pace with accelerating energy demand and the rapid growth of gigascale compute,” Drew Baglino, Heron’s founder and chief executive, said in a statement. “Too much of today’s electrical infrastructure is passive, clunky equipment designed decades ago. At Heron we are manifesting an alternative future, where modern power electronics enable projects to come online faster, the grid to operate more reliably, and scale affordably.”