You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

A conversation with essayist Emily Raboteau about hope and her new book, Lessons for Survival.

It was another Emily who wrote, “‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers,” but Emily Raboteau’s Lessons for Survival: Mothering Against “the Apocalypse” builds on that notion in a fresh and literal fashion. The collection of essays, out March 12, is loosely structured around Raboteau’s attempt to see and photograph all of the paintings in the Audubon Mural Project in her New York City neighborhood, Washington Heights. In practice, though, the book is an honest look at the overlapping injustices of our current age and an inspiring suggestion — by way of example — of how to move forward and survive.

Optimism, though, is not easy. Scrutinizing the idea of “resilience” in the face of climate change, Raboteau notes that the word means something different to communities of color who’ve managed retreats for decades — including her grandmother, Mabel, who fled her home of Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, after Raboteau’s grandfather was shot and killed by a white man who faced no legal repercussions. Visiting the territory of Palestine, Raboteau witnesses the water crisis in the Middle East being weaponized against the region’s poorest communities; in Alaska, she sees traditional ways of living in the Arctic slipping out of reach for the survivors and descendants of residential schools, government-run institutions that aimed to forcefully assimilate Indigenous children.

Present in every essay is Raboteau’s perspective as a mother, which is fierce in demanding a better world while also necessarily believing that one is within reach. Even the bird murals — the tundra swan, the burrowing owls — become messengers of hope.

I spoke with Raboteau ahead of the book’s release about the adjective “mothering,” learning resilience from one’s community, and why “apocalypse” doesn’t have to be a bad word. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

I wanted to ask about the change in preposition from the title essay, “Lessons in Survival,” to Lessons for Survival, the book’s title. There’s an ever-so-slight change in meaning with that switch. Was it something you were thinking about?

What I like about the essay title from which the book title grows is that “Lessons in Survival” implies I’m the one who’s receiving lessons. To me, this is not a book that is offering — well, I don’t want to say it’s not offering guidance, but I hope it’s offering a feeling of camaraderie in the confusing and distressing times of the polycrisis we find ourselves in. It’s an acknowledgment of the bewilderment many of us are feeling and includes examples from people I think are wiser than myself about how to move through times like this.

Rather than being the author who’s offering lessons, I think of myself as more of a narrator who is interested in receiving lessons and witnessing examples of survival, and then sharing those with the reader.

You wrote the essays in this collection between 2015 and 2023. What was it like going back and revisiting your older essays? Is there anything that particularly strikes you about how your worldview has shifted over the years?

One of the earliest essays included in this collection, from 2015, is about playgrounds. In New York City, playgrounds are common spaces where all kinds of classes and races mix. Yet they are also spaces where a lot of parents encounter conversations about school choice that often are really coded conversations about race and class. And that can feel distressing. The concern that drove that essay, which is about imbalances of power, is a concern that drives all of the essays in this book. It’s not a coincidence that the less desirable school districts overlap with poor neighborhoods, which are also the areas with the highest rates of pollution and asthma. I’m really interested in staring grim asymmetries of power in the face, trying to dismantle them, and figuring out my position within them.

Another early essay was the Palestine one, about Israeli settler colonialism plus the installation of renewable energy and clean-water systems in the terrorized Arab communities of the West Bank's South Hebron Hills, which was actually my first explicit piece of environmental writing. Another thing that unites all these essays is the narrative perspective of a mother: How do I raise ethical and safe human beings in a world that feels in many ways like it’s unraveling? I had no idea when I was revising and expanding that essay for this collection that the war between Gaza and Israel would be unfolding, yet I hope that it offers readers some context about the decades of conflict that led to this war and that it gives a sense of apartheid — a sense of a literal imbalance of power vis a vis electricity, but also water access. I wasn’t in Gaza, I was in the West Bank. But still, you get a sense of what life is like for Palestinians there, and it’s only grown worse since the time I did the investigative reporting for that piece.

I really loved that essay — there’s a line when you’re going through border control in Israel that describes motherhood as “invisibility and power.” I was underlining and highlighting and circling that.

Motherhood confers a kind of moral authority, but there’s also the sort of thinking like, “Oh, but you can’t be too much of a threat. You’re just a mom.” In this context, I was using motherhood as a way to pass more easily through customs and then through a checkpoint. But I’ve been thinking lately about how radical a perspective and a stance motherhood is. To say, “You know, what I want more than anything is for all of our kids to live.” That’s my political stance: I want all of them to live.

The book’s subtitle, “Mothering against ‘the Apocalypse,’” seems like a call to arms — that fighting the apocalypse requires mothers. How do you see the role of mothers as different or set apart from the role of fathers or people without children when it comes to standing against the polycrisis?

Mothering is a very powerful way of thinking about the nurture and care that I feel is required to meet the moment. I also want to be sensitive to the fact that people who are not biological parents can also be mothering. We all have the power to be that; it’s why we also understand you can’t get between a mama bear and her cubs. You’re going to get torn apart. There’s great power in that role: Whether we are mothers or not, we may be mothering, and so — how did you just put it, that maybe mothers are required in the fight? It’s more like the fight requires the action of mothering.

It was also important to me to add scare quotes around “the apocalypse” in the subtitle because I felt it would be offensive to activists to suggest that the future is foreclosed. I wanted to suggest we’re in an apocalyptic mode, but I didn’t want that term to stop people from action.

Something else about the term apocalypse: I have a friend, Ayana Mathis, who is writing about the apocalypse in literature right now, and she reminded me that the ancient Greek term means literally “to unveil.”

I didn’t know that!

The way we use it so often is about the end times, the end game. We have a lot of biblical imagery we associate with it: fire and floods and locusts. But what the root word means is “unveiling,” which I find really exciting to think about. Yes, we’re in an apocalyptic moment and let’s actually accept that. It’s an opportunity for waking up.

There’s a tension in the book between the outdoors as being a kind of haven — it’s where your kids play, it’s where you go on walks and see the bird murals, it’s where you have your garden — and the outdoors as a source of danger, from the air pollution from car exhaust to the rivers rising. How do you manage to reconcile those two things?

I don’t want to suggest I feel the perils come from nature. The perils come from what is being done to specific communities, like the Black and brown communities that we’ve chosen to live in. My family lives in a frontline community, and so the solace that we get nevertheless from being outdoors, especially in parks in New York City, is crucial and restorative. In this book, I’m interested in holding cognitive dissonance. Nature is both a space that is imperiled, a place that has been plundered and abused, but it can also be a place of joy, a place that is home, and a place that is worth protecting and trying to alter to make safer for more people. I wanted to write about what it feels like for all those things to be true at once.

The sense of community in this book really struck me, particularly in some of the essays in the section “At the Risk of Spoiling Dinner.” Do you think of community-building as being one of your lessons for survival?

Absolutely. I’m really glad you picked up on that because I think it’s the number one thing. It’s driven by the feelings of care and love that I also associate with mothering. Ancillary to that is thinking about relationships not merely between parent and child but also in my extended and beloved community. That section that you’re referring to is an admission: “I can’t handle my degree of anxiety over how bad and scary things are by myself.” If I can’t talk about it among the people I love and trust and also listen to what they’re saying, I’m at risk of being stuck in this feeling, and that’s not helpful to anybody. It was a mobilizing gesture for me.

For a year, I committed to asking people in my social network both online and in person how they were feeling the effects of climate change in their bodies and in their local habitat. I did that because climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe has said one of the best ways we can combat climate change is to bridge the gap between the number of us who are appropriately fearful and the number of us who actually talk about it. I was like, “Well, that’s an interesting idea. Let me try to put that into practice.” Was it an uncomfortable subject at dinner tables? Sometimes. But mostly everybody had it at the tip of their tongue; they were just so ready and grateful for the question.

I wanted to ask about the photos in the book, particularly the ones of the Audubon Mural Project. You use the word “document,” but the pictures are also intentional and creative — there are almost always people in your frames, and the photos seem to be as much about capturing a small part of Washington Heights as they are about recording the mural. Was there a moment when photography became a creative endeavor for you in addition to being a log, or were those two things always the same?

I think they’re really interrelated. There’s also a third thing: a therapeutic hobby. Some people find repetitive gestures like running or knitting to be ways of calming down their brain, and for me, especially during the Trump years, that’s when I began photographing the birds. It was a way I understood I could relax. It was a repetitive gesture, a thing I knew I could do to make myself feel better because I was getting outside.

These bird murals are sites of beauty and also memorials. Some of these birds are expected to be extinct by 2080 if we continue our current trajectory. So photographing was a way of paying attention and being in community and, you’re right, it was also an artistic project. Including people on the same plane as the birds was important even in thinking about endangerment: When we think about conservation, we often think about wildlife and wild places, but I also really wanted to be intentional in thinking about who’s endangered in the community I live in and the nation I live in.

What do you do, now, to survive?

One thing that I do to survive is name that there are so many feelings involved. Knowing that some of the feelings are in the space of fear, despair, anger, rage, bewilderment, and confusion — dark feelings, for lack of a better term — and understanding that I don’t linger in any of those feelings, that there are strategies to get out of them.

For me, it’s photographing birds in my neighborhood and gardening, getting my hands in the soil and contemplating and engaging with the most basic miracle that out of a seed comes a plant. That helps me to move into the space of those other feelings of being in this time, which are more in the space of hopefulness and gratitude. The feelings that come from being in a community with others, working through the hard stuff. Feelings of purpose and a deep sense of meaning. What I’m trying to say is: Understanding you don’t have to linger in the dark side; there are strategies to move into the space of action and unity.

Normally I end these interviews by asking if you feel optimistic, but I actually left that question off this time because your book feels so hopeful that it would have been redundant of me to ask.

I’m really glad that you shared that with me. It’s a hard balance to strike in writing because we want to be honest. I was thinking about that, but I almost always tried to end my essays in a place of hope — even if it’s an image, even if it’s tinged by ambiguity, to still lean toward hopefulness. That was important to me because who am I to linger in the opposite of hope when there are so many people working?

I want to amplify, also, the people and peoples who’ve lived through existential threats before and to highlight their resilience. Because that’s how we get through this — with lessons. I’m not the one who’s offering them; I’m trying really hard to learn them so I can offer them to my children.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

On a late-night House vote, Tesla’s slump, and carbon credits

Current conditions: Tropical storm Chantal has a 40% chance of developing this weekend and may threaten Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas • French far-right leader Marine Le Pen is campaigning on a “grand plan for air conditioning” amid the ongoing record-breaking heatwave in Europe • Great fireworks-watching weather is in store tomorrow for much of the East and West Coasts.

The House moved closer to a final vote on President Trump’s “big, beautiful bill” after passing a key procedural vote around 3 a.m. ET on Thursday morning. “We have the votes,” House Speaker Mike Johnson told reporters after the rule vote, adding, “We’re still going to meet” Trump’s self-imposed July 4 deadline to pass the megabill. A floor vote on the legislation is expected as soon as Thursday morning.

GOP leadership had worked through the evening to convince holdouts, with my colleagues Katie Brigham and Jael Holzman reporting last night that House Freedom Caucus member Ralph Norman of North Carolina said he planned to advance the legislation after receiving assurances that Trump would “deal” with the Inflation Reduction Act’s clean energy tax credits, particularly for wind and solar energy projects, which the Senate version phases out more slowly than House Republicans wanted. “It’s not entirely clear what the president could do to unilaterally ‘deal with’ tax credits already codified into law,” Brigham and Holzman write, although another Republican holdout, Representative Chip Roy of Texas, made similar allusions to reporters on Wednesday.

Tesla delivered just 384,122 cars in the second quarter of 2025, a 13.5% slump from the 444,000 delivered in the same quarter of 2024, marking the worst quarterly decline in the company’s history, Barron’s reports. The slump follows a similarly disappointing Q1, down 13% year-over-year, after the company’s sales had “flatlined for the first time in over a decade” in 2024, InsideEVs adds.

Despite the drop, Tesla stock rose 5% on Wednesday, with Wedbush analyst Dan Ives calling the Q2 results better than some had expected. “Fireworks came early for Tesla,” he wrote, although Barron’s notes that “estimates for the second quarter of 2025 started at about 500,000 vehicles. They started to drop precipitously after first-quarter deliveries fell 13% year over year, missing Wall Street estimates by some 40,000 vehicles.”

The European Commission proposed its 2040 climate target on Wednesday, which, for the first time, would allow some countries to use carbon credits to meet their emissions goals. EU Commissioner for Climate, Net Zero, and Clean Growth Wopke Hoekstra defended the decision during an appearance on Euronews on Wednesday, saying the plan — which allows developing nations to meet a limited portion of their emissions goals with the credits — was a chance to “build bridges” with countries in Africa and Latin America. “The planet doesn’t care about where we take emissions out of the air,” he separately told The Guardian. “You need to take action everywhere.” Green groups, which are critical of the use of carbon credits, slammed the proposal, which “if agreed [to] by member states and passed by the EU parliament … is then supposed to be translated into an international target,” The Guardian writes.

Around half of oil executives say they expect to drill fewer wells in 2025 than they’d planned for at the start of the year, according to a Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas survey. Of the respondents at firms producing more than 10,000 barrels a day, 42% said they expected a “significant decrease in the number of wells drilled,” Bloomberg adds. The survey further indicates that Republican policy has been at odds with President Trump’s “drill, baby, drill” rhetoric, as tariffs have increased the cost of completing a new well by more than 4%. “It’s hard to imagine how much worse policies and D.C. rhetoric could have been for U.S. E&P companies,” one anonymous executive said in the report. “We were promised by the administration a better environment for producers, but were delivered a world that has benefited OPEC to the detriment of our domestic industry.”

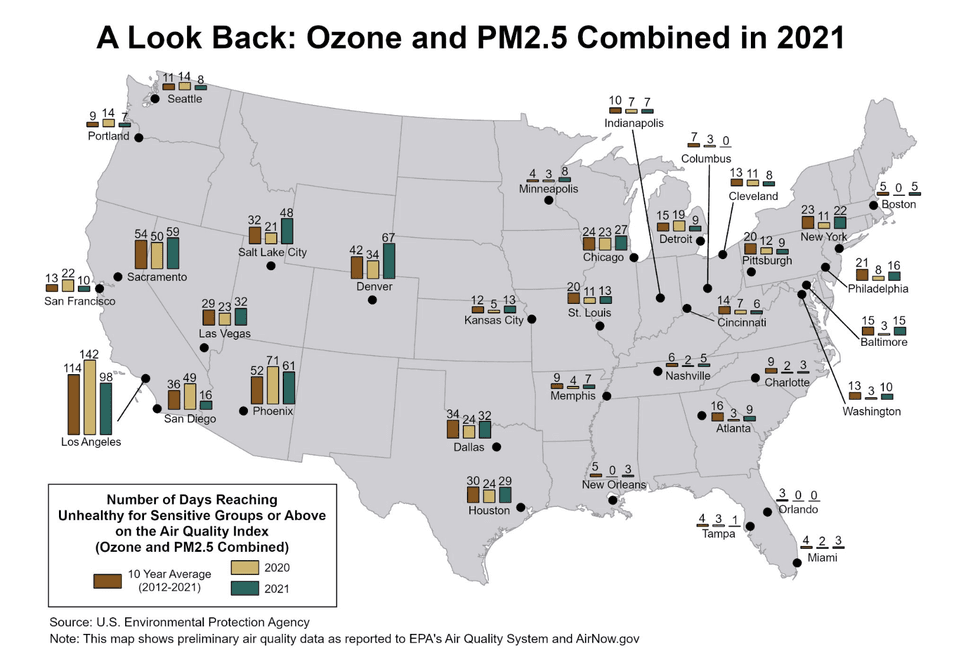

Fine-particulate air pollution is strongly associated with lung cancer-causing DNA mutations that are more traditionally linked to smoking tobacco, a new study by researchers at the University of California, San Diego, and the National Cancer Institute has found. The researchers looked at the genetic code of 871 non-smokers’ lung tumors in 28 regions across Europe, Africa, and Asia and found that higher levels of local air pollution correlated with more cancer-driving mutations in the respective tumors.

Surprisingly, the researchers did not find a similar genetic correlation among non-smokers exposed to secondhand smoke. George Thurston, a professor of medicine and population health at New York University, told Inside Climate News that a potential reason for this result is that fine-particulate air pollution — which is emitted by cars, industrial activities, and wildfires — is more widespread than exposure to secondhand smoke. “We are engulfed in fossil-fuel-burning pollution every single day of our lives, all day long, night and day,” he said, adding, “I feel like I’m in the Matrix, and I’m the only one that took the red pill. I know what’s going on, and everybody else is walking around thinking, ‘This stuff isn’t bad for your health.’” Today, non-smokers account for up to 25% of lung cancer cases globally, with the worst air quality pollution in the United States primarily concentrated in the Southwest.

National TV news networks aired a combined 4 hours and 20 minutes of coverage about the record-breaking late-June temperatures in the Midwest and East Coast — but only 4% of those segments mentioned the heat dome’s connection to climate change, a new report by Media Matters found.

“We had enough assurance that the president was going to deal with them.”

A member of the House Freedom Caucus said Wednesday that he voted to advance President Trump’s “big, beautiful bill” after receiving assurances that Trump would “deal” with the Inflation Reduction Act’s clean energy tax credits – raising the specter that Trump could try to go further than the megabill to stop usage of the credits.

Representative Ralph Norman, a Republican of North Carolina, said that while IRA tax credits were once a sticking point for him, after meeting with Trump “we had enough assurance that the president was going to deal with them in his own way,” he told Eric Garcia, the Washington bureau chief of The Independent. Norman specifically cited tax credits for wind and solar energy projects, which the Senate version would phase out more slowly than House Republicans had wanted.

It’s not entirely clear what the president could do to unilaterally “deal with” tax credits already codified into law. Norman declined to answer direct questions from reporters about whether GOP holdouts like himself were seeking an executive order on the matter. But another Republican holdout on the bill, Representative Chip Roy of Texas, told reporters Wednesday that his vote was also conditional on blocking IRA “subsidies.”

“If the subsidies will flow, we’re not gonna be able to get there. If the subsidies are not gonna flow, then there might be a path," he said, according to Jake Sherman of Punchbowl News.

As of publication, Roy has still not voted on the rule that would allow the bill to proceed to the floor — one of only eight Republicans yet to formally weigh in. House Speaker Mike Johnson says he’ll, “keep the vote open for as long as it takes,” as President Trump aims to sign the giant tax package by the July 4th holiday. Norman voted to let the bill proceed to debate, and will reportedly now vote yes on it too.

Earlier Wednesday, Norman said he was “getting a handle on” whether his various misgivings could be handled by Trump via executive orders or through promises of future legislation. According to CNN, the congressman later said, “We got clarification on what’s going to be enforced. We got clarification on how the IRAs were going to be dealt with. We got clarification on the tax cuts — and still we’ll be meeting tomorrow on the specifics of it.”

Neither Norman nor Roy’s press offices responded to a request for comment.

The foreign entities of concern rules in the One Big Beautiful Bill would place gigantic new burdens on developers.

Trump campaigned on cutting red tape for energy development. At the start of his second term, he signed an executive order titled, “Unleashing Prosperity Through Deregulation,” promising to kill 10 regulations for each new one he enacted.

The order deems federal regulations an “ever-expanding morass” that “imposes massive costs on the lives of millions of Americans, creates a substantial restraint on our economic growth and ability to build and innovate, and hampers our global competitiveness.” It goes on to say that these regulations “are often difficult for the average person or business to understand,” that they are so complicated that they ultimately increase the cost of compliance, as well as the risks of non-compliance.

Reading this now, the passage echoes the comments I’ve heard from industry groups and tax law experts describing the incredibly complex foreign entities of concern rules that Congress — with the full-throated backing of the Trump administration — is about to impose on clean energy projects and manufacturers. Under the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, wind and solar, as well as utility-scale energy storage, geothermal, nuclear, and all kinds of manufacturing projects will have to abide by restrictions on their Chinese material inputs and contractual or financial ties with Chinese entities in order to qualify for tax credits.

“Foreign entity of concern” is a U.S. government term referring to entities that are “owned by, controlled by, or subject to the jurisdiction or direction of” any of four countries — Russia, Iran, North Korea, and most importantly for clean energy technology, China.

Trump’s tax bill requires companies to meet increasingly strict limits on the amount of material from China they use in their projects and products. A battery factory starting production next year, for example, would have to ensure that 60% of the value of the materials that make up its products have no connection to China. By 2030, the threshold would rise to 85%. The bill lays out similar benchmarks and timelines for clean electricity projects, as well as other kinds of manufacturing.

But how companies should calculate these percentages is not self-evident. The bill also forbids companies from collecting the tax credits if they have business relationships with “specified foreign entities” or “foreign-influenced entities,” terms with complicated definitions that will likely require guidance from the Treasury for companies to be sure they pass the test.

Regulatory uncertainty could stifle development until further guidance is released, but how long that takes will depend on if and when the Trump administration prioritizes getting it done. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act contains a lot of other new tax-related provisions that were central to the Trump campaign, including a tax exemption for tips, which are likely much higher on the department’s to-do list.

Tax credit implementation was a top priority for the Biden administration, and even with much higher staffing levels than the department currently has, it took the Treasury 18 months to publish initial guidance on foreign entities of concern rules for the Inflation Reduction Act’s electric vehicle tax credit. “These things are so unbelievably complicated,” Rachel McCleery, a former senior advisor at the Treasury under Biden, told me.

McCleery questioned whether larger, publicly-owned companies would be able to proceed with major investments in things like battery manufacturing plants until that guidance is out. She gave the example of a company planning to pump out 100,000 batteries per year and claim the per-kilowatt-hour advanced manufacturing tax credit. “That’s going to look like a pretty big number in claims, so you have to be able to confidently and assuredly tell your shareholder, Yep, we’re good, we qualify, and that requires a certification” by a tax counsel, she said. To McCleery, there’s an open question as to whether any tax counsel “would even provide a tax opinion for publicly-traded companies to claim credits of this size without guidance.”

John Cornwell, the director of policy at the Good Energy Collective, which conducts research and advocacy for nuclear power, echoed McCleery’s concerns. “Without very clear guidelines from the Treasury and IRS, until those guidelines are in place, that is going to restrict financing and investment,” Cornwell told me.

Understanding what the law requires will be the first challenge. But following it will involve tracking down supply chain data that may not exist, finding alternative suppliers that may not be able to fill the demand, and establishing extensive documentation of the origins of components sourced through webs of suppliers, sub-suppliers, and materials processors.

The Good Energy Collective put out an issue brief this week describing the myriad hurdles nuclear developers will face in trying to adhere to the tax credit rules. Nuclear plants contain thousands of components, and documenting the origin of everything from “steam generators to smaller items like specialized fasteners, gaskets, and electronic components will introduce substantial and costly administrative burdens,” it says. Additionally the critical minerals used in nuclear projects “often pass through multiple processing stages across different countries before final assembly,” and there are no established industry standards for supply chain documentation.

Beyond the documentation headache, even just finding the materials could be an issue. China dominates the market for specialized nuclear-grade materials manufacturing and precision component fabrication, the report says, and alternative suppliers are likely to charge premiums. Establishing new supply chains will take years, but Trump’s bill will begin enforcing the sourcing rules in 2026. The rules will prove even more difficult for companies trying to build first-of-a-kind advanced nuclear projects, as those rely on more highly specialized supply chains dominated by China.

These challenges may be surmountable, but that will depend, again, on what the Treasury decides, and when. The Department’s guidance could limit the types of components companies have to account for and simplify the documentation process, or it could not. But while companies wait for certainty, they may also be racking up interest. “The longer there are delays, that can have a substantial risk of project success,” Cornwell said.

And companies don’t have forever. Each of the credits comes with a phase-out schedule. Wind manufacturers can only claim the credits until 2028. Other manufacturers have until 2030. Credits for clean power projects will start to phase down in 2034. “Given the fact that a lot of these credits start lapsing in the next few years, there’s a very good chance that, because guidance has not yet come out, you’re actually looking at a much smaller time frame than than what is listed in the bill,” Skip Estes, the government affairs director for Securing America’s Energy Future, or SAFE, told me.

Another issue SAFE has raised is that the way these rules are set up, the foreign sourcing requirements will get more expensive and difficult to comply with as the value of the tax credits goes down. “Our concern is that that’s going to encourage companies to forego the credit altogether and just continue buying from the lowest common denominator, which is typically a Chinese state-owned or -influenced monopoly,” Estes said.

McCleery had another prediction — the regulations will be so burdensome that companies will simply set up shop elsewhere. “I think every industry will certainly be rethinking their future U.S. investments, right? They’ll go overseas, they’ll go to Canada, which dumped a ton of carrots and sticks into industry after we passed the IRA,” she said.

“The irony is that Republicans have historically been the party of deregulation, creating business friendly environments. This is completely opposite, right?”