This article is exclusively

for Heatmap Plus subscribers.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Why farmers are becoming the new nemeses of the solar and wind industries

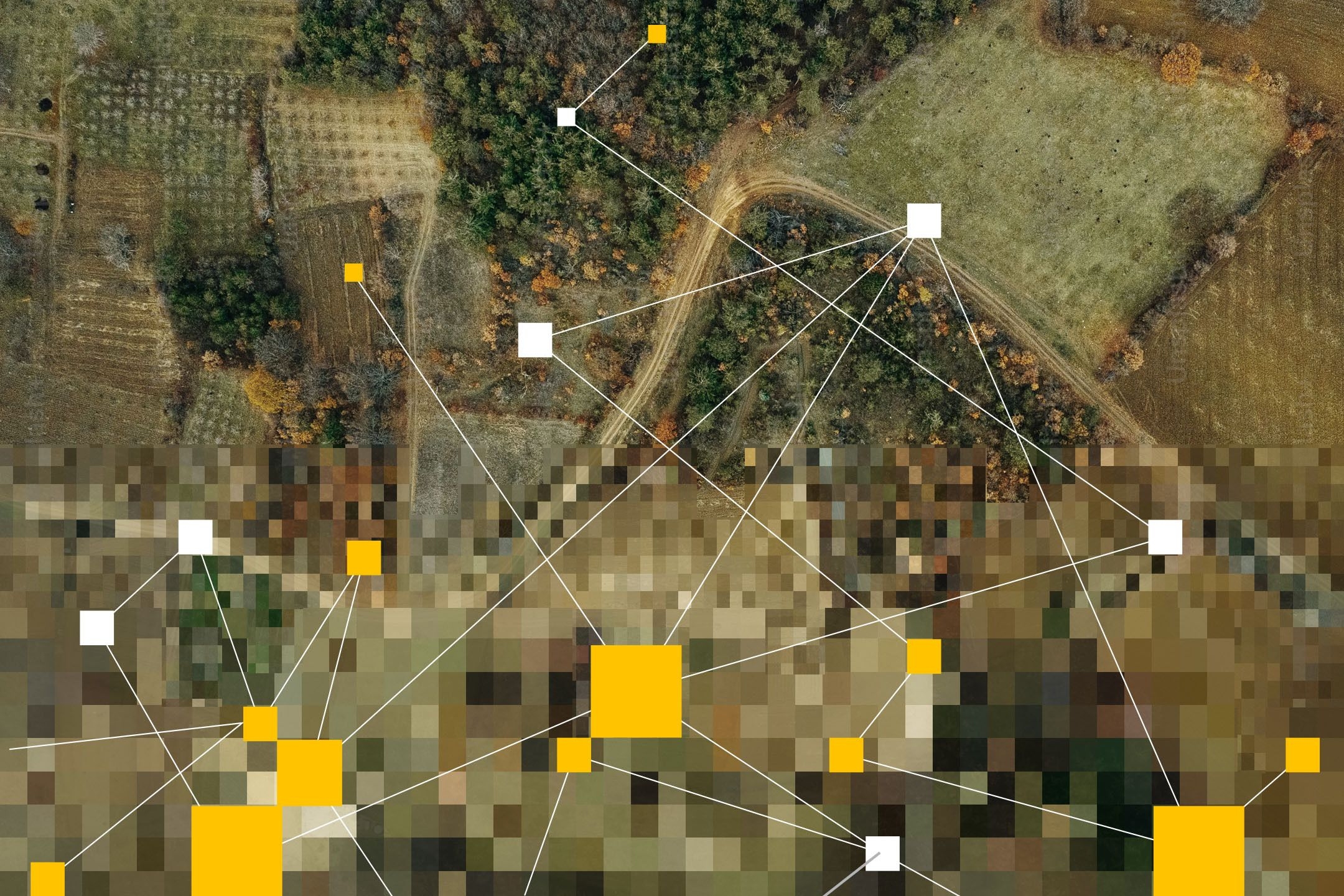

Farms are fast becoming one of the most powerful opponents to renewable energy in the United States, second perhaps only to the fossil fuel industry. And it’s frighteningly unclear how developers will resolve this problem – or if they even can.

As solar and wind has grown rapidly across the country, so too have protests against solar and wind power on “prime farmland,” a loose term used by industry and government officials to describe property best suited for growing lots of crops. Towns and counties are banning the construction of solar and wind farms on prime farmland. State regulators – including those run by Democrats – are restricting renewable development on prime farmland, and members of Congress are looking at cutting off or restricting federal funds to projects on prime farmland.

In theory, meeting our country’s climate goals and industry needs should require very little farmland. But those same wide expanses flush with sunlight and gusts of wind sought after by developers happen to often be used by farmers: A USDA study released this year found more than 90% of wind turbines and 70% of solar farms in rural areas were sited on agricultural land.

It would be easy for an activist or energy nerd to presume this farmland free-for-all is being driven by outside actors or adverse incentives (and there’s a little bit of that going on, as we’ll get to).

However, weeks of reporting – and internal Heatmap News datasets – have revealed to me that farmland opposition actually has a devilishly simple explanation: many large farm owners are just plain hostile to land use changes that could potentially, or even just hypothetically, impact their capacity to grow more crops.

This means there is no easy solution and as I’ll explain, it is unclear whether the renewables sector’s efforts to appear more accommodating to agricultural businesses – most notably agri-voltaics – will stem the tide of local complaints from rural farmers.

“This is a new land use that is very quickly accelerating across the country and one of the major reactions is just to that fact,” Ethan Winter of American Farmland Trust, a nonprofit promoting solar education in farm communities, told me. “These are people who’ve been farming this land for generations in some instances. The idea of doing anything to take it out of agricultural production is just hard for them, for their community, and it’s about the culture of their community, and if solar is something that can be considered compatible with agriculture.”

Over 40% of all restrictive ordinances and moratoriums in Heatmap Pro's database are occurring in counties with large agricultural workforces.

In fact, our internal data via Heatmap Pro has found that agricultural employment can be a useful predictor of whether a community will oppose the deployment of renewables. It's particularly salient where there's large-scale, capital-intensive farming, likely because the kind of agriculture requiring expensive machinery, costly chemicals, and physical and financial infrastructure — think insurance and loans — indicates that farming is the economic cornerstone of that entire community.

Resentment against renewables is pronounced in the Corn Belt, but it’s also happening even in the bluest of states like Connecticut, where state environmental regulators have recommended against developing on prime farmland and require additional permits to build on preferred fertile soils. Or New York, where under pressure from farming groups including the state Farm Bureau, the state legislature last year included language in a new permitting authority law limiting the New York Power Authority from approving solar and wind on “land used in agricultural production” unless the project was agrivoltaics, which means it allows simultaneous farming of the property. The state legislature is now looking at additional curbs on siting projects in farmland as it considers new permitting legislation.

Deanna Fox, head of the New York Farm Bureau, explained to me that her organization’s bottom-up structure essentially means its positions are a consensus of its grassroots farm worker membership. And those members really don’t trust renewables to be safe for farmland.

“What happens when those solar arrays no longer work, or they become antiquated? Or farmland loses its agricultural designation and becomes zoned commercial? How does that impact ag districting in general? Does that land just become commercial? Can it go back to being agricultural land?” Fox asked. “If you were to talk to a group of farmers about solar, I would guarantee none of them would say anything about the emotional aspect of it. I don’t think that's what it really is for them. [And] if it’s emotional, it’s wrapped around the economics of it.”

Surveys of farmers have hinted that fears could be assuaged if developers took steps to make their projects more harmonious with agricultural work. As we reported last week, a survey by the independent research arm of the Solar Energy Industries Association found up to 70% of farmers they spoke with said they were “open to large-scale solar” but many sought stipulations for dual usage of the land for farming – a practice known as agrivoltaics.

Clearly, agrivoltaics and other simultaneous use strategies are what the industry wants to promote. As we hit send on last week’s newsletter, I was strolling around RE+, renewable energy’s largest U.S. industry conference. Everywhere I turned, I found publicity around solar and farming.

The Department of Energy even got in on the action. At the same time as the conference, the department chose to announce a new wave of financial prizes for companies piloting simultaneous solar energy and farming techniques.

“In areas where there has been a lot of loss of farmland to development, solar is one more factor that I think has worried folks in some communities,” Becca Jones-Albertus, director of DOE’s solar energy technologies office, told me during an interview at the conference. However agri-voltaics offer “a really exciting strategy because it doesn’t make this an either or. It’s a yes and.”

It remains to be seen whether these attempts at harmony will resolve any of the discord.

One industry practice being marketed to farm communities that folks hope will soften opposition is sheep grazing at solar farms. At RE+, The American Solar Grazing Association, an advocacy group, debuted a documentary about the practice at the conference and had an outdoor site outside the showroom with sheep chilling underneath solar panel frames. The sheep display had a sign thanking sponsors including AES, Arevon, BP, EDF Renewables, and Pivot Energy.

Some developers like Avangrid have found grazing to be a useful way to mitigate physical project risks at solar farms in the Pacific Northwest. Out in rural Oregon and Washington, unkempt grasslands can present a serious fire risk. So after trying other methods, Avangrid partnered with an Oregon rancher, Cameron Krebs, who told me he understands why some farmers are skeptical about developers coming into their neck of the woods.

“Culturally speaking, this is agricultural land. These are communities that grow wheat and raise cattle. So my peers, when they put in the solar farms and they see it going out of production, that really bothers the community in general,” he said.

But Krebs doesn’t see solar farms with grazing the same way.

“It’s a retooling. It may not be corn production anymore. But we’re still going to need a lot of resources. We’re still going to need tire shops. I think there is a big fear that the solar companies will take the land out of production and then the meat shops and the food production would suffer because we don’t have that available on the landscape, but I think we can have utility scale solar that is healthy for our communities. And that really in my mind means honoring that soil with good vegetation.”

It’s important to note, however, that grazing can’t really solve renewables’ farmland problem. Often grazing is most helpful in dry Western desert. Not to mention sheep aren’t representative of all livestock – they’re a small percentage. And Heatmap Pro’s database has found an important distinction between farms focused on crops versus livestock — the latter isn’t as predisposed to oppose renewable energy.

Ground zero for the future of renewables on farmland is Savion's proposed Oak Run project in Ohio, which at up to 800 megawatts of generation capacity would be the state’s largest solar farm. The developer also plans to let farmers plant and harvest crops in between the solar arrays, making it the nation’s largest agri-voltaics site if completed.

But Oak Run is still being opposed by nearby landowners and local officials citing impacts to farmland. At Oak Run’s proposed site, neighboring township governments have passed resolutions opposing construction, as has the county board of commissioners, and town and county officials sued to undo Oak Run’s approval at the Ohio Power Siting Board. Although that lawsuit was unsuccessful, its backers want to take the matter to the state Supreme Court.

Some of this might be tied to the pure fact Ohio is super hostile to renewables right now. Over a third of counties in the state have restricted or outright banned solar and wind projects, according to Heatmap Pro’s database.

But there’s more at play here. The attorney representing town and county officials is Jack Van Kley, a lawyer and former state government official who remains based in Ohio and who has represented many farms in court for myriad reasons. I talked to Van Kley last week for an hour about why he opposes renewables projects (“they’re anything but clean in my opinion”), his views on global warming (“I don’t get involved in the dispute over climate change”) and a crucial fact that might sting: He says at least roughly two thirds of his clientele are farmers or communities reliant on agricultural businesses.

“It’s neighbor against neighbor in these communities,” he told me. “You’ve got a relatively low number of farmers who want to lease their land so that the solar companies can put solar panels on them for thirty or forty years, and it’s just a few landowners that are profiting from these projects.”

Van Kley spoke to a concern voiced by his clients I haven’t really heard addressed by solar developers much: overall impacts to irrigation. Specifically, he said an outsized concern among farmers is simply how putting a solar or wind farm adjacent or close to their property will impact how groundwater and surface water moves in the area, which can impact somebody’s existing agricultural drainage infrastructure.

“If you do that next to another property that is being farmed, you’ll kill the crop because you’ll flood the crop,” he claimed. “This is turning out to be a big issue for farmers who are opposing these facilities.”

Some have tried to paint Van Kley as funded or assisted by the fossil fuel lobby or shadowy actors. Van Kley has denied any involvement in those kinds of backroom dealings. While there’s glimpses of evidence gas and coal money plays at least a minor role with other characters fomenting opposition in the state, I really have no evidence of him being one of these people right now. It’s much easier and simpler to reason that he’s being paid by another influential sect – large landowners, many of whom work in agriculture.

That’s the same conclusion John Boeckl reached. Boeckl, an Army engineer, is one of the property owners leasing land for construction of the Oak Run project. He supports Oak Run being built and has submitted testimony in the legal challenge over its approvals. Though Boeckl certainly wants to know more about who is funding the opposition and has his gripes with neighbors who keep putting signs on his property that say “no solar on prime farmland,” he hasn’t witnessed any corporate skullduggery from shadowy outside entities.

“I think it’s just farmers being farmers,” he said. “They don’t want to be told what to do with their land.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

A conversation with Center for Rural Innovation founder and Vermont hative Matt Dunne.

This week’s conversation is with Matt Dunne, founder of the nonprofit Center for Rural Innovation, which focuses on technology, social responsibility, and empowering small, economically depressed communities.

Dunne was born and raised in Vermont, where he still lives today. He was a state legislator in the Green Mountain State for many years. I first became familiar with his name when I was in college at the state’s public university, reporting on his candidacy for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination in 2016. Dunne ultimately lost a tight race to Sue Minter, who then lost to current governor Phil Scott, a Republican.

I can still remember how back in 2016, Dunne’s politics then presaged the kind of rural empathy and economic populism now en vogue and rising within the Democratic Party. Dunne endorsed Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential bid and was backed by the state’s AFL-CIO; Minter, a more establishment Democrat, stayed out of the 2016 primary and underperformed in the general election. It doesn’t surprise me now to see Dunne emerging with novel, nuanced perspectives on how advanced technological infrastructure can succeed in rural America. So I decided to chat with him about the state of data center development today.

The following chat has been lightly edited for clarity.

So first of all, can you tell our readers about your organization in case they’re unfamiliar?

We founded this social enterprise back in 2017 because the economic gap between urban and rural turned into a chasm. We traced the core reasons and it was the winners and losers of the tech economy. There were millions and millions of jobs created from the great recession, but the problem was that it was almost exclusively in urban areas, in the services sectors like consulting, finance, and tech. At the end of the day, we believe in the age of the internet there should be no limit to where high-quality technology jobs should thrive.

We work with communities across the country that are rural and looking to add technology as a component to their economy. We help them with strategies – tech accelerators, tech accountability programs, co-working spaces, all the other stuff you need to create a vibrant place where those kinds of companies can emerge so people can come back, come home. We work with 43 regions across 25 states that are all on this journey together and help them secure the resources to execute on that journey.

One of the reasons I wanted to speak with you is your history in Vermont. I went to the University of Vermont, and I loved living there, but there aren’t jobs to keep kids there which is still a huge disappointment to young folks who love living in the state.

At the same time the state reflects many of the same signals we see in Heatmap Pro data around advanced industrial development. Large land owners bristle at new projects regardless of their political party, and Democratic voters are more inclined to side more with locavorism than a YIMBY growth-minded approach.

How do your Vermonter roots inform your work, and do they affect the ways you see the conflicts over new advanced tech infrastructure?

What we’ve seen in Vermont after the Great Recession is that there’s lots of available space and a population that’s aged significantly.

This all impacted my outlook as a community development person, and now as a leader of a social enterprise. We need to be thinking proactively about what an economically healthy community looks like and how we ensure we have places importing cash and exporting value in a way that doesn’t destroy what’s amazing about these rural places. You pretty quickly land on tech, as well as maybe some design-related manufacturing where the ideas are local.

To make it clear, we’re building infrastructure for technology communities which is different from building technology infrastructure itself. That’s an important distinction. It’s about giving them the tools to stand up a tech accelerator and have a co-working space that creates community. A good co-working space has good programming, allows for remote workers to go to a place, and you can have those virtuous collisions that lead to something else. A collaboration. A volunteer project. Whatever it is. Having hack-a-thons, lectures or demonstrations on the latest AI technology that can be used. Youth programming around robotics. If you can create a space where that happens, you create a lot of synergy, which is important in smaller markets – you have to be intentional with all of this.

Okay, so considering those practices, what do you think of the way data center development is going?

For the record, I spent six and a half years at Google and was hired at first because of data centers. At the time, I saw Google try to build a big data center in a community of less than 10,000 people in secret, and it didn’t go well because it just doesn’t work, and that’s how I got my job there.

There is a right way to come into a community with a data center or frankly any kind of global company infrastructure project, and there’s a wrong way to do it. The right way is being as transparent as possible, knowing full well that when a brand name is mentioned, the price goes through the roof for the land. There does have to be some level of confidentiality when you’re ready to go, but once you can, you have to be proactive with it.

You have to be a really good steward on the impacts, whether they’re electrical demand or water demand. It’s about being clear, it’s about figuring out how to mitigate it, and it’s about maintaining your commitment to 100% renewable energy even as you’re bringing online data centers. Oh, and it’s about having a real financial commitment to make sure the community can economically diversify away from being overly dependent on the data center, on that one industry. The data center developers know full well that they’ll create a lot of construction jobs but that’s not going to be a good, sustainable employer. Frankly, the history of rural places is littered with communities that are too dependent on one industry, one company, and that hasn’t

What does that look like from a policy perspective and a community relations perspective?

I think there are models emerging, including from Microsoft, Google, and others, about what good entry and strong commitments look like. It would be great if someone put a line in the sand about 2% of capex going to a community to diversify the economy. It would be great if companies put a reasonable time horizon out there to replace potable water through technology or other kinds of supports. It would be great to see commitments to ratepayers that say people won’t have to foot the bill for increased demand.

Here’s the part we focus on more because we’re not as focused on site selection: Rural America is likely to shoulder the burden of data center infrastructure just like they shouldered the burden of energy production infrastructure. The question at the end of the day is, how do we make sure those communities see the upside? How do we make sure they can leverage tech capacity inside these data centers to be able to have more agency and chart their own economic futures? That’s what we’re really focused on because if you do that, it doesn’t have to be a repeat of the extractive processes of the past, where rural places were used for cheap land and low-wage workers. They can instead be places with lots of land available and incredible innovation, new enterprises and solving the world’s problems.

Plus more of the week’s biggest development fights.

Botetourt County, Virginia – Google has released its water use plans for a major data center in Virginia after a local news outlet argued regulators couldn’t withhold that information under public records laws.

Montana – Ladies, gentlemen, and everyone in between, we have a freshly dead wind farm.

Oklahoma County, Oklahoma – A huge rally is scheduled in Oklahoma City this weekend in support of ending wind and solar farm construction in the state.

Mingo County, West Virginia – Coal country is rebelling against data centers.

Mesa County, Colorado – This county’s government is implementing a new legal standard for energy storage – and it is causing problems.

The administration has begun shuffling projects forward as court challenges against the freeze heat up.

The Trump administration really wants you to think it’s thawing the freeze on renewable energy projects. Whether this is a genuine face turn or a play to curry favor with the courts and Congress, however, is less clear.

In the face of pressures such as surging energy demand from artificial intelligence and lobbying from prominent figures on the right, including the wife of Trump’s deputy chief of staff, the Bureau of Land Management has unlocked environmental permitting processes in recent weeks for a substantial number of renewable energy projects. Public documents, media reports, and official agency correspondence with stakeholders on the ground all show projects that had ground to a halt now lurching forward.

What has gone relatively unnoticed in all this is that the Trump administration has used this momentum to argue against a lawsuit filed by renewable energy groups challenging Trump’s permitting freeze. In January, for instance, Heatmap was first to report that the administration had lifted its ban on eagle take permits for wind projects. As we predicted at the time, after easing that restriction, Trump’s Justice Department has argued that the judge in the permitting freeze case should reject calls for an injunction. “Arguments against the so-called Eagle Permit Ban are perhaps the easiest to reject. [The Fish and Wildlife Service] has lifted the temporary pause on the issuance of Eagle take permits,” DOJ lawyers argued in a legal brief in February.

On February 26, E&E News first reported on Interior’s permitting freeze melting, citing three unnamed career agency officials who said that “at least 20 commercial-scale” solar projects would advance forward. Those projects include each of the seven segments of the Esmeralda mega-project that Heatmap was first to report was killed last fall. E&E News also reported that Jove Solar in Arizona, the Redonda and Bajada solar projects in California and three Nevada solar projects – Boulder Solar III, Dry Lake East and Libra Solar – will proceed in some fashion. Libra Solar received its final environmental approval in December but hasn’t gotten its formal right-of-way for construction.

Since then, Heatmap has learned of four other projects on the list, all in Nevada: Mosey Energy Center, Kawich Energy Center, Purple Sage Energy Center and Rock Valley Energy Center.

Things also seem to be moving on the transmission front in ways that will benefit solar. BLM posted the final environmental impact statement for upgrades to NextEra’s GridLance West transmission project in Nevada, which is expected to connect to solar facilities. And NV Energy’s Greenlink North transmission line is now scheduled to receive a final federal decision in June.

On wind, the administration silently advanced the Lucky Star transmission line in Wyoming, which we’ve covered as a bellwether for the state of the permitting process. We were first to report that BLM sent local officials in Wyoming a draft environmental review document a year ago signaling that the transmission line would be approved — then the whole thing inexplicably ground to a halt. Now things are moving forward again. In early February, BLM posted the final environmental review for Lucky Star online without any public notice or press release.

There are certainly reasons why Trump would allow renewables development to move forward at this juncture.

The president is under incredible pressure to get as much energy as possible onto the electric grid to power AI data centers without causing undue harm to consumers’ pocketbooks. According to the Wall Street Journal, the oil industry is urging him to move renewables permitting forward so Democrats come back to the table on a permitting deal.

Then there’s the MAGAverse’s sudden love affair with solar energy. Katie Miller, wife of White House deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller, has suddenly become a pro-solar advocate at the same time as a PR campaign funded by members of American Clean Power claims to be doing paid media partnerships with her. (Miller has denied being paid by ACP or the campaign.) Former Trump senior adviser Kellyanne Conway is now touting polls about solar’s popularity for “energy security” reasons, and Trump pollster Tony Fabrizio just dropped a First Solar-funded survey showing that roughly half of Trump voters support solar farms.

This timing is also conspicuously coincidental. One day before the E&E News story, the Justice Department was granted an extension until March 16 to file updated rebuttals in the freeze case before any oral arguments or rulings on injunctions. In other court filings submitted by the Justice Department, BLM career staff acknowledge they’ve met with people behind multiple solar projects referenced in the lawsuit since it was filed. It wouldn’t be surprising if a big set of solar projects got their permitting process unlocked right around that March 16 deadline.

Kevin Emmerich, co-founder of Western environmental group Basin & Range Watch, told me it’s important to recognize that not all of these projects are getting final approvals; some of this stuff is more piecemeal or procedural. As an advocate who wants more responsible stewardship of public lands and is opposed to lots of this, Emmerich is actually quite troubled by the way Trump is going back on the pause. That is especially true after the Supreme Court’s 2025 ruling in the Seven Counties case, which limited the scope of environmental reviews, not to mention Trump-era changes in regulation and agency leadership.

“They put a lot of scrutiny on these projects, and for a while there we didn’t think they were going to move, period,” Emmerich told me. “We’re actually a little bit bummed out about this because some of these we identified as having really big environmental impacts. We’re seeing this as a perfect storm for those of us worried about public land being taken over by energy because the weakening of NEPA is going to be good for a lot of these people, a lot of these developers.”

BLM would not tell me why this thaw is happening now. When reached for comment, the agency replied with an unsigned statement that the Interior Department “is actively reviewing permitting for large-scale onshore solar projects” through a “comprehensive” process with “consistent standards” – an allusion to the web of review criteria renewable energy developers called a de facto freeze on permits. “This comprehensive review process ensures that projects — whether on federal, state, or private lands — receive appropriate oversight whenever federal resources, permits, or consultations are involved.”