You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Kamala Harris quickly rang up endorsements from Democratic elected officials and convention delegates Sunday afternoon after President Joe Biden ended his re-election campaign, making Vice President Harris the likeliest Democratic nominee for the presidency of the United States. Many of these plaudits came from figures in the climate policy space, but few were quite as vociferous as the one from Gina McCarthy, a director of the Environmental Protection Agency under President Obama and White House climate advisor under Biden.

“Vice President Harris would kick ass against Trump,” she said in a statement. “She has spent her whole life committed to justice, fighting for the underdog, and making sure that no one is above the law. She will fight every day for all Americans to have access to clean air, clean water, and a healthy environment.”

When Harris has had the chance to formulate climate action on her own — as the attorney general of California, as a U.S. senator, as a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2020 — it has tended to be aggressive in its timelines for decarbonization and heavily focused on the harms that fossil fuel extraction and processing inflict on marginalized communities.

As vice president, however, she has been subsumed into the rollout of both the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. In some cases, the programs she’s pitched and praised have an organic connection to her own personal policy work — a grant program for electric school buses, for instance, the launch of which was the source of one of her more enduring Kamala-isms: “Who doesn’t love a yellow school bus?”

Assuming she wins the party’s nomination and then, finally, the White House, a Kamala Harris climate agenda would no doubt look much like Biden’s. To people who’ve been paying attention all along, however, there’s no reason to think she couldn’t push the country even more zealously toward decarbonizing.

For one, there’s the historical record. Harris not only endorsed Green New Deal legislation in 2019, she also put out a climate plan during her campaign that included $10 trillion of public and private spending and called for reaching net-zero by 2045, achieving a carbon neutral electric grid by 2030, no new fossil fuel leasing on public lands, and a carbon pollution fee. While expansive, Harris’s plan was not the work of someone like Jay Inslee, who has legislated on climate for years, or Bernie Sanders, who was willing to simply outbid his fellow candidates on progressive policy, but her climate policy was the process of consulting with climate activists. In fact, her team had reached out to Inslee’s after he dropped out for advice on climate, Jamal Raad, Inslee’s campaign communications director, told me.

“If we jump in the Wayback Machine, [Harris] was one of the most ambitious presidential candidates in the 2020 primary cycle,” Justin Guay, program director at Quadrature Climate Foundation, told me. “She had the largest proposed spending plan of any candidate not named Bernie. She promised a sum 10 times that of the greatest climate president we’ve ever had, Joe Biden.” Importantly, he added, she focused on “sticks, not just carrots,” including investigating and bringing lawsuits against fossil fuel companies, as she’d done in California. This, he said, is “red meat for the climate base.”

Where she did stand out in the Senate, on the campaign trail, and in the Biden administration was in her focus on environmental justice, an issue combining green politics and racial justice that she used to reach out to the party’s left wing. By the time the she was picked to be President Biden’s vice presidential nominee, she had won the praise of both the youth-led Sunrise Movement (which has since protested outside her Southern California home and notably withheld its support from Biden during his reelection campaign) and Evergreen Action, a climate policy group built by former Inslee staffers. “She made environmental justice central to her climate plans on the presidential campaign,” said Raad, an Evergreen Action cofounder.

In the summer of 2019, she joined up with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez on a bill that would have required all climate-related legislation to undergo a review of its effect on “frontline communities,” those living adjacent to energy-related facilities, which tend to be disproportionately populated by poor people of color, and created offices of climate equity within the Congressional Budget Office and the Office of Management and Budget.

While this particular piece of legislation went nowhere, the motivating ideas have been all over the Biden-Harris White House’s policy agenda — in tax benefits directed toward projects in “energy communities;” in the Justice40 Initiative, which aims to direct 40% of climate and related spending to flow toward disadvantaged communities; and in the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, a.k.a. “green banks,” aimed at making climate-friendly investing more affordable.

That’s all great, Raad told me. But he also added, “What’s more relevant has been how central she’s made climate in her vice presidency as one of her top priorities.” Harris reached out to Raad and others in the run-up to the IRA’s passage, he said. “She held a town hall. She barnstormed the country. As far as folks wanting further momentum in the next presidency, that’s the more relevant development — that she wanted to be associated with climate action.”

Whatever her policy priorities as president, they would have to fit between the lines of what would be, at best, narrow majorities in both chambers of Congress, limited by the filibuster and reconciliation process, along with large policy shifts that any new administration will have to deal with, such as the expiration of key portions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2025. It will be a far distance from the heady days of the 2020 Democratic primary campaign, when Harris eagerly participated in a bidding war between the candidates for the most aggressive and expansive climate program — less Frank Capra, more Alan J. Pakula.

“The reality is that the climate movement should focus as much, if not more, on creating the conditions that force politicians to act on climate as we do pushing for candidates with a hawkish climate policy platform to begin with,” Guay told me. “That was the greatest lesson from the Joe Biden era. He was no climate hawk when he entered the 2020 primaries,” but thanks to decades of unrelenting pressure and calls for more policy ambition, “he emerged the most powerful climate president we’ve ever had.”

Raad, too, emphasized the importance of realpolitik at this point in history. Having a president willing to put herself on the line for climate policy is important — “even if we don’t get major legislation done,” he told me. “We need to make sure the IRA is implemented effectively in the fullest way possible. We need a very careful eye towards writing regulations that are as effective as possible so they’re not getting overturned by Federalist Society judges.” Getting money out the door will be key, he said, “and that’s why we need an advocate in the White House.”

With assistance from Jeva Lange and Robinson Meyer.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act is one signature away from becoming law and drastically changing the economics of renewables development in the U.S. That doesn’t mean decarbonization is over, experts told Heatmap, but it certainly doesn’t help.

What do we do now?

That’s the question people across the climate change and clean energy communities are asking themselves now that Congress has passed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which would slash most of the tax credits and subsidies for clean energy established under the Inflation Reduction Act.

Preliminary data from Princeton University’s REPEAT Project (led by Heatmap contributor Jesse Jenkins) forecasts that said bill will have a dramatic effect on the deployment of clean energy in the U.S., including reducing new solar and wind capacity additions by almost over 40 gigawatts over the next five years, and by about 300 gigawatts over the next 10. That would be enough to power 150 of Meta’s largest planned data centers by 2035.

But clean energy development will hardly grind to a halt. While much of the bill’s implementation is in question, the bill as written allows for several more years of tax credit eligibility for wind and solar projects and another year to qualify for them by starting construction. Nuclear, geothermal, and batteries can claim tax credits into the 2030s.

Shares in NextEra, which has one of the largest clean energy development businesses, have risen slightly this year and are down just 6% since the 2024 election. Shares in First Solar, the American solar manufacturer, are up substantially Thursday from a day prior and are about flat for the year, which may be a sign of investors’ belief that buyer demand for solar panels will persist — or optimism that the OBBBA’s punishing foreign entity of concern requirements will drive developers into the company’s arms.

Partisan reversals are hardly new to climate policy. The first Trump administration gleefully pulled the rug from under the Obama administration’s power plant emissions rules, and the second has been thorough so far in its assault on Biden’s attempt to replace them, along with tailpipe emissions standards and mileage standards for vehicles, and of course, the IRA.

Even so, there are ways the U.S. can reduce the volatility for businesses that are caught in the undertow. “Over the past 10 to 20 years, climate advocates have focused very heavily on D.C. as the driver of climate action and, to a lesser extent, California as a back-stop,” Hannah Safford, who was director for transportation and resilience in the Biden White House and is now associate director of climate and environment at the Federation of American Scientists, told Heatmap. “Pursuing a top down approach — some of that has worked, a lot of it hasn’t.”

In today’s environment, especially, where recognition of the need for action on climate change is so politically one-sided, it “makes sense for subnational, non-regulatory forces and market forces to drive progress,” Safford said. As an example, she pointed to the fall in emissions from the power sector since the late 2000s, despite no power plant emissions rule ever actually being in force.

“That tells you something about the capacity to deliver progress on outcomes you want,” she said.

Still, industry groups worry that after the wild swing between the 2022 IRA and the 2025 OBBA, the U.S. has done permanent damage to its reputation as a business-friendly environment. Since continued swings at the federal level may be inevitable, building back that trust and creating certainty is “about finding ballasts,” Harry Godfrey, the managing director for Advanced Energy United’s federal priorities team, told Heatmap.

The first ballast groups like AEU will be looking to shore up is state policy. “States have to step up and take a leadership role,” he said, particularly in the areas that were gutted by Trump’s tax bill — residential energy efficiency and electrification, transportation and electric vehicles, and transmission.

State support could come in the form of tax credits, but that’s not the only tool that would create more certainty for businesses — considering the budget cuts states will face as a result of Trump’s tax bill, it also might not be an option. But a lot can be accomplished through legislative action, executive action, regulatory reform, and utility ratemaking, Godfrey said. He cited new virtual power plant pilot programs in Virginia and Colorado, which will require further regulatory work to “to get that market right.”

A lot of work can be done within states, as well, to make their deployment of clean energy more efficient and faster. Tyler Norris, a fellow at Duke University's Nicholas School of the Environment, pointed to Texas’ “connect and manage” model for connecting renewables to the grid, which allows projects to come online much more quickly than in the rest of the country. That’s because the state’s electricity market, ERCOT, does a much more limited study of what grid upgrades are needed to connect a project to the grid, and is generally more tolerant of curtailing generation (i.e. not letting power get to the grid at certain times) than other markets.

“As Texas continues to outpace other markets in generator and load interconnections, even in the absence of renewable tax credits, it seems increasingly plausible that developers and policymakers may conclude that deeper reform is needed to the non-ERCOT electricity markets,” Norris told Heatmap in an email.

At the federal level, there’s still a chance for, yes, bipartisan permitting reform, which could accelerate the buildout of all kinds of energy projects by shortening their development timelines and helping bring down costs, Xan Fishman, senior managing director of the energy program at the Bipartisan Policy Center, told Heatmap. “Whether you care about energy and costs and affordability and reliability or you care about emissions, the next priority should be permitting reform,” he said.

And Godfrey hasn’t given up on tax credits as a viable tool at the federal level, either. “If you told me in mid-November what this bill would look like today, while I’d still be like, Ugh, that hurts, and that hurts, and that hurts, I would say I would have expected more rollbacks. I would have expected deeper cuts,” he told Heatmap. Ultimately, many of the Inflation Reduction Act’s tax credits will stick around in some form, although we’ve yet to see how hard the new foreign sourcing requirements will hit prospective projects.

While many observers ruefully predicted that the letter-writing moderate Republicans in the House and Senate would fold and support whatever their respective majorities came up with — which they did, with the sole exception of Pennsylvania Republican Brian Fitzpatrick — the bill also evolved over time with input from those in the GOP who are not openly hostile to the clean energy industry.

“You are already seeing people take real risk on the Republican side pushing for clean energy,” Safford said, pointing to Alaska Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski, who opposed the new excise tax on wind and solar added to the Senate bill, which earned her vote after it was removed.

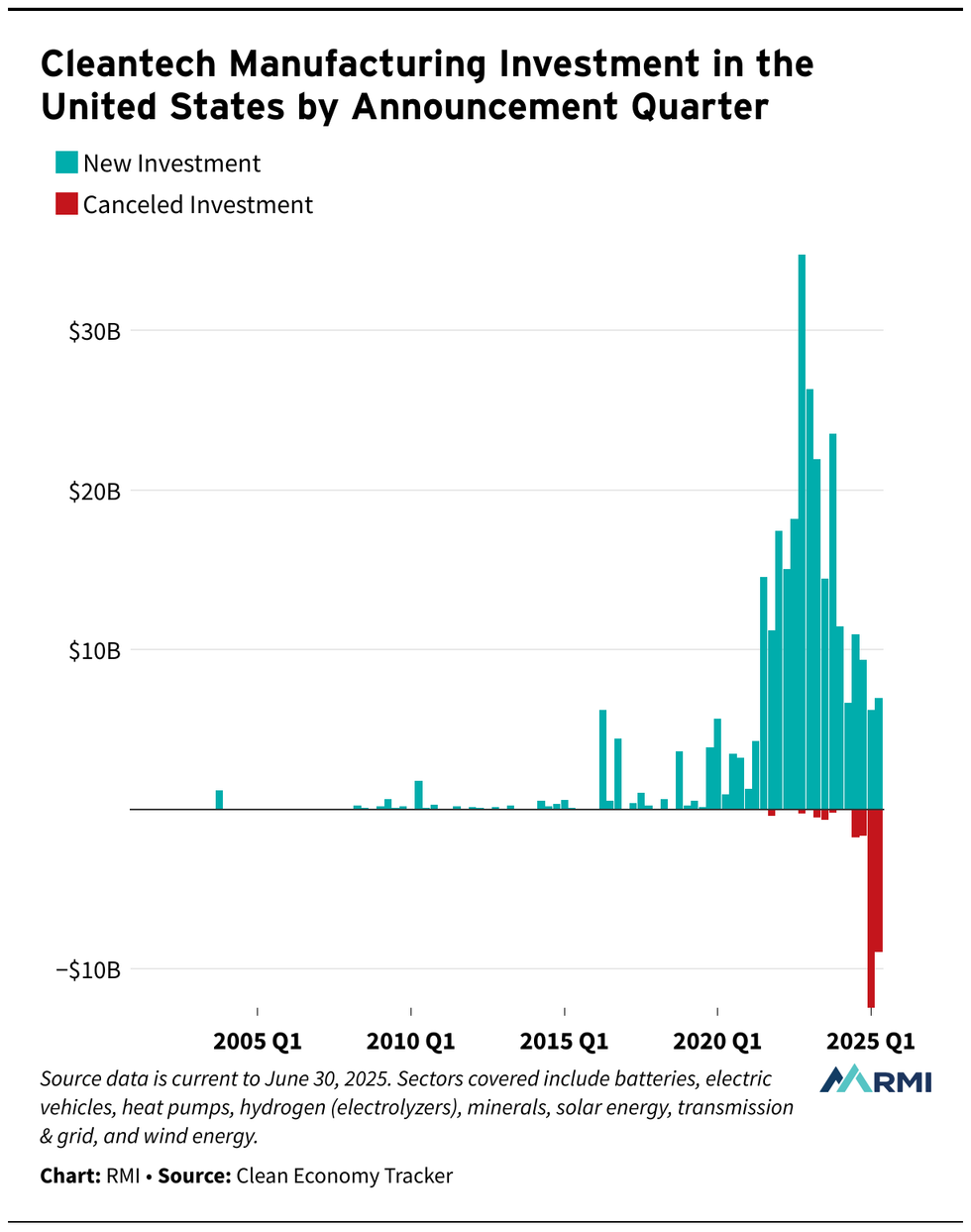

Some damage has already been done, however. Canceled clean energy investments adds up to $23 billion so far this year, compared to just $3 billion in all of 2024, according to the decarbonization think tank RMI. And that’s before OBBBA hits Trump’s desk.

The start-and-stop nature of the Inflation Reduction Act may lead some companies, states, local government and nonprofits to become leery of engaging with a big federal government climate policy again.

“People are going to be nervous about it for sure,” Safford said. “The climate policy of the future has to be polycentric. Even if you have the political opportunity to make a big swing again, people will be pretty gun shy. You will need to pursue a polycentric approach.”

But to Godfrey, all the back and forth over the tax credits, plus the fact that Republicans stood up to defend them in the 11th hour, indicates that there is a broader bipartisan consensus emerging around using them as a tool for certain energy and domestic manufacturing goals. A future administration should think about refinements that will create more enduring policy but not set out in a totally new direction, he said.

Albert Gore, the executive director of the Zero Emissions Transportation Alliance, was similarly optimistic that tax credits or similar incentives could work again in the future — especially as more people gain experience with electric vehicles, batteries, and other advanced clean energy technologies in their daily lives. “The question is, how do you generate sufficient political will to implement that and defend it?” he told Heatmap. “And that depends on how big of an economic impact does it have, and what does it mean to the American people?”

Ultimately, Fishman said, the subsidy on-off switch is the risk that comes with doing major policy on a strictly partisan basis.

“There was a lot of value in these 10-year timelines [for tax credits in the IRA] in terms of business certainty, instead of one- or two- year extensions,” Fishman told Heatmap. “The downside that came with that is that it became affiliated with one party. It was seen as a partisan effort, and it took something that was bipartisan and put a partisan sheen on it.”

The fight for tax credits may also not be over yet. Before passage of the IRA, tax credits for wind and solar were often extended in a herky-jerky bipartisan fashion, where Democrats who supported clean energy in general and Republicans who supported it in their districts could team up to extend them.

“You can see a world where we have more action on clean energy tax credits to enhance, extend and expand them in a future congress,” Fishman told Heatmap. “The starting point for Republican leadership, it seemed, was completely eliminating the tax credits in this bill. That’s not what they ended up doing.”

On a late-night House vote, Tesla’s slump, and carbon credits

Current conditions: Tropical storm Chantal has a 40% chance of developing this weekend and may threaten Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas • French far-right leader Marine Le Pen is campaigning on a “grand plan for air conditioning” amid the ongoing record-breaking heatwave in Europe • Great fireworks-watching weather is in store tomorrow for much of the East and West Coasts.

The House moved closer to a final vote on President Trump’s “big, beautiful bill” after passing a key procedural vote around 3 a.m. ET on Thursday morning. “We have the votes,” House Speaker Mike Johnson told reporters after the rule vote, adding, “We’re still going to meet” Trump’s self-imposed July 4 deadline to pass the megabill. A floor vote on the legislation is expected as soon as Thursday morning.

GOP leadership had worked through the evening to convince holdouts, with my colleagues Katie Brigham and Jael Holzman reporting last night that House Freedom Caucus member Ralph Norman of North Carolina said he planned to advance the legislation after receiving assurances that Trump would “deal” with the Inflation Reduction Act’s clean energy tax credits, particularly for wind and solar energy projects, which the Senate version phases out more slowly than House Republicans wanted. “It’s not entirely clear what the president could do to unilaterally ‘deal with’ tax credits already codified into law,” Brigham and Holzman write, although another Republican holdout, Representative Chip Roy of Texas, made similar allusions to reporters on Wednesday.

Tesla delivered just 384,122 cars in the second quarter of 2025, a 13.5% slump from the 444,000 delivered in the same quarter of 2024, marking the worst quarterly decline in the company’s history, Barron’s reports. The slump follows a similarly disappointing Q1, down 13% year-over-year, after the company’s sales had “flatlined for the first time in over a decade” in 2024, InsideEVs adds.

Despite the drop, Tesla stock rose 5% on Wednesday, with Wedbush analyst Dan Ives calling the Q2 results better than some had expected. “Fireworks came early for Tesla,” he wrote, although Barron’s notes that “estimates for the second quarter of 2025 started at about 500,000 vehicles. They started to drop precipitously after first-quarter deliveries fell 13% year over year, missing Wall Street estimates by some 40,000 vehicles.”

The European Commission proposed its 2040 climate target on Wednesday, which, for the first time, would allow some countries to use carbon credits to meet their emissions goals. EU Commissioner for Climate, Net Zero, and Clean Growth Wopke Hoekstra defended the decision during an appearance on Euronews on Wednesday, saying the plan — which allows developing nations to meet a limited portion of their emissions goals with the credits — was a chance to “build bridges” with countries in Africa and Latin America. “The planet doesn’t care about where we take emissions out of the air,” he separately told The Guardian. “You need to take action everywhere.” Green groups, which are critical of the use of carbon credits, slammed the proposal, which “if agreed [to] by member states and passed by the EU parliament … is then supposed to be translated into an international target,” The Guardian writes.

Around half of oil executives say they expect to drill fewer wells in 2025 than they’d planned for at the start of the year, according to a Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas survey. Of the respondents at firms producing more than 10,000 barrels a day, 42% said they expected a “significant decrease in the number of wells drilled,” Bloomberg adds. The survey further indicates that Republican policy has been at odds with President Trump’s “drill, baby, drill” rhetoric, as tariffs have increased the cost of completing a new well by more than 4%. “It’s hard to imagine how much worse policies and D.C. rhetoric could have been for U.S. E&P companies,” one anonymous executive said in the report. “We were promised by the administration a better environment for producers, but were delivered a world that has benefited OPEC to the detriment of our domestic industry.”

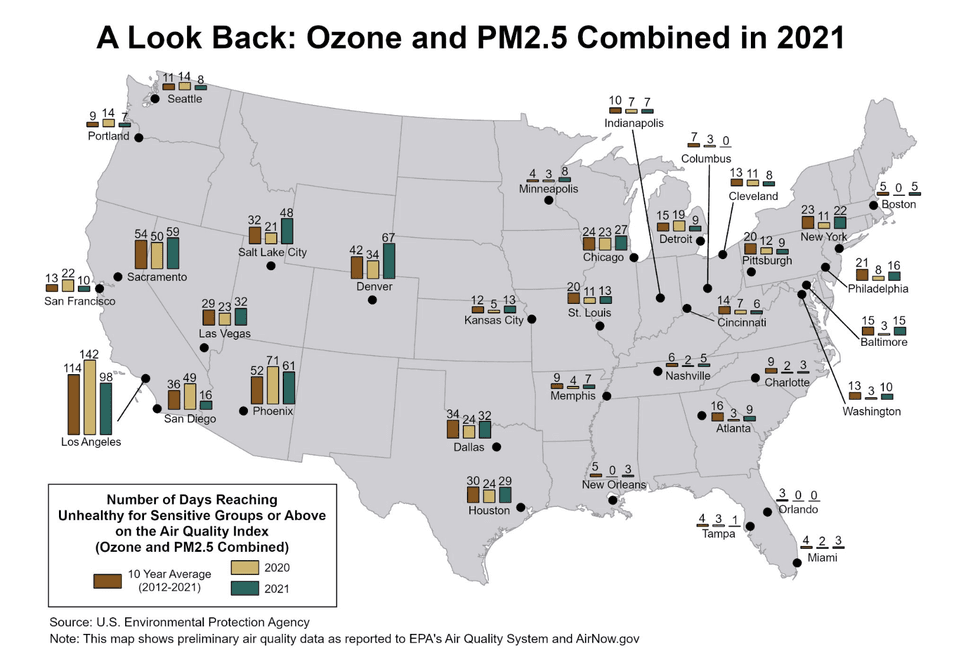

Fine-particulate air pollution is strongly associated with lung cancer-causing DNA mutations that are more traditionally linked to smoking tobacco, a new study by researchers at the University of California, San Diego, and the National Cancer Institute has found. The researchers looked at the genetic code of 871 non-smokers’ lung tumors in 28 regions across Europe, Africa, and Asia and found that higher levels of local air pollution correlated with more cancer-driving mutations in the respective tumors.

Surprisingly, the researchers did not find a similar genetic correlation among non-smokers exposed to secondhand smoke. George Thurston, a professor of medicine and population health at New York University, told Inside Climate News that a potential reason for this result is that fine-particulate air pollution — which is emitted by cars, industrial activities, and wildfires — is more widespread than exposure to secondhand smoke. “We are engulfed in fossil-fuel-burning pollution every single day of our lives, all day long, night and day,” he said, adding, “I feel like I’m in the Matrix, and I’m the only one that took the red pill. I know what’s going on, and everybody else is walking around thinking, ‘This stuff isn’t bad for your health.’” Today, non-smokers account for up to 25% of lung cancer cases globally, with the worst air quality pollution in the United States primarily concentrated in the Southwest.

National TV news networks aired a combined 4 hours and 20 minutes of coverage about the record-breaking late-June temperatures in the Midwest and East Coast — but only 4% of those segments mentioned the heat dome’s connection to climate change, a new report by Media Matters found.

“We had enough assurance that the president was going to deal with them.”

A member of the House Freedom Caucus said Wednesday that he voted to advance President Trump’s “big, beautiful bill” after receiving assurances that Trump would “deal” with the Inflation Reduction Act’s clean energy tax credits – raising the specter that Trump could try to go further than the megabill to stop usage of the credits.

Representative Ralph Norman, a Republican of North Carolina, said that while IRA tax credits were once a sticking point for him, after meeting with Trump “we had enough assurance that the president was going to deal with them in his own way,” he told Eric Garcia, the Washington bureau chief of The Independent. Norman specifically cited tax credits for wind and solar energy projects, which the Senate version would phase out more slowly than House Republicans had wanted.

It’s not entirely clear what the president could do to unilaterally “deal with” tax credits already codified into law. Norman declined to answer direct questions from reporters about whether GOP holdouts like himself were seeking an executive order on the matter. But another Republican holdout on the bill, Representative Chip Roy of Texas, told reporters Wednesday that his vote was also conditional on blocking IRA “subsidies.”

“If the subsidies will flow, we’re not gonna be able to get there. If the subsidies are not gonna flow, then there might be a path," he said, according to Jake Sherman of Punchbowl News.

As of publication, Roy has still not voted on the rule that would allow the bill to proceed to the floor — one of only eight Republicans yet to formally weigh in. House Speaker Mike Johnson says he’ll, “keep the vote open for as long as it takes,” as President Trump aims to sign the giant tax package by the July 4th holiday. Norman voted to let the bill proceed to debate, and will reportedly now vote yes on it too.

Earlier Wednesday, Norman said he was “getting a handle on” whether his various misgivings could be handled by Trump via executive orders or through promises of future legislation. According to CNN, the congressman later said, “We got clarification on what’s going to be enforced. We got clarification on how the IRAs were going to be dealt with. We got clarification on the tax cuts — and still we’ll be meeting tomorrow on the specifics of it.”

Neither Norman nor Roy’s press offices responded to a request for comment.