On paper, the names look like a roster of nursing home residents: Rita and Katrina, Ike and Gustav, Harvey and Laura and Delta.

“I mean, literally, those are all hurricanes since 2005,” James Hiatt, the founder of the environmental justice organization For a Better Bayou, told me. “The storm that hit southwest Louisiana before that was Hurricane Audrey in 1957. So before 2005, we’d gone 50 years without really any storm.”

Now, though, few American communities are more obviously in the crosshairs of climate change than Louisiana’s Cameron Parish. It’s not just the influx of supercharged storms, which have repeatedly wiped out homes and driven those with the means to get out to flee north. The 5,000-or-so remaining residents of the parish, which borders Texas and the Gulf of Mexico in Louisiana’s lower lefthand corner, also share their home with three of the nation’s eight currently operational liquefied natural gas export facilities, according to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and the Energy Information Administration. One more is under construction, according to FERC, with two more waiting to break ground and even more in the pipeline — including Calcasieu Pass 2, or CP2, a would-be $10 billion export facility and the largest yet proposed in the U.S., the fate of which has been cast into limbo by the Biden administration’s pause on new LNG export terminal permits.

It is now the Department of Energy’s job to determine whether new terminals are in the “public interest” once their climate impacts are considered. It’s a directive that has ignited debate around the energy security of U.S. allies in Europe, the complicated accounting of methane leaks, and the jurisdiction of the DOE. What has fallen through the cracks in the national conversation, though, is the direct impact this decision has on communities like Cameron, which have been fighting for such a reconsideration for years.

“In southwest Louisiana, where I live, my air here smells like rotten eggs or chemicals every day,” Roishetta Ozane, the founder of Vessel Project of Louisiana, a local mutual aid and environmental justice organization, told me. A mother of six who started the Vessel Project after losing her home to hurricanes Laura and Delta in 2020, Ozane stressed that “we have above-average poverty rates, above-average cancer rates, and above-average toxins in the air. And all of that is due to the fact that we are surrounded by petrochemical, plastic-burning, and industrial facilities, including LNG facilities.”

Hiatt, a Lake Charles native, told me something similar. “The other night, [a terminal] was flaring like crazy, and people were just like, ‘Well, we gotta put up with that if we live here,’” he told me sadly. “That’s a lack of imagination of what better could be.”

Activists like Ozane and Hiatt — and the United Nations — refer to places like Cameron Parish, Calcasieu Parish directly to its north, and the stretch of the Mississippi River in Louisiana known as “Cancer Alley” as sacrifice zones. “The industry wants people to believe that this is rural land, that nobody lives here, that it is just wetlands and swamp,” Ozane said.

LNG export terminals cool natural gas into its liquid form to prepare it for overseas shipping, an energy-intensive process that releases pollutants that environmental groups claim are underreported. Such pollutants often have known health risks, including sulfur dioxide (linked to wheezing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness), volatile organic compounds (suspected and proven carcinogens that also cause eye, nose, and throat irritation, nausea, and damage to livers, kidneys, and the nervous system), black soot (linked to asthma and heart attacks), and carbon monoxide (which can cause organ and tissue damage). All that, of course, is in addition to methane, the base of natural gas and a potent planet-warming greenhouse gas that has cascading global effects, including hurricane intensification.

The region’s history of slavery has made the land around Cameron Parish cheap and easy to exploit, which is part of the reason for the area’s high concentration of terminals. “A lot of predominantly Black communities and predominantly Black neighborhoods, very low-income white neighborhoods, and fishermen towns are where these facilities are located,” Ozane went on. “It’s easy for them to get land there because those masses of land are owned by only a few people — a small family who can say yes to the money and sell that land to industry.”

Politicians, lobbyists, and interest groups like the American Petroleum Institute — which recently announced an eight-figure media campaign promoting natural gas — like to argue that LNG export terminals create American jobs. Both Ozane and Hiatt were rueful when I asked about the industry helping to lift up locals, though. “If the jobs are so good, and the folks are getting the jobs in these communities that are surrounded by these projects, then why is Louisiana still the poorest state in the nation?” Ozane asked me. “Why is our minimum wage still the lowest? And why do we have the highest unemployment rate?” She went on, “We have all of these billion-dollar industries here: They are not hiring local people.”

Hiatt emphasized that it’s hard to understand how little the community is benefitting unless you see it for yourself. “If you drive through Cameron, it looks like the hurricane happened yesterday in a lot of places,” he said. “All these churches are just skeletons, just the framework of what was once there. There’s no grocery store — there’s nothing. If economic prosperity looks like that, then no thank you.” He paused, then corrected himself: “It’s definitely economically prosperous for the owners of these companies,” which are based out of state in places like Virginia and Houston, he said.

These companies often don’t pay state or local taxes; the abatement for Calcasieu Pass LNG alone is valued at $184 million annually, or more than $36,000 per person in Cameron Parish every year — roughly $2,000 more than the area’s average annual income.

While climate activists have celebrated the Biden administration’s LNG pause, local organizers were more reserved in their praise. “We’re not going to take a victory lap here because there’s so much more to do,” Hiatt said, reminding me that “this fight did not happen overnight. This fight for environmental justice has been going for over 40 years in Louisiana.”

Kaniela Ing, the director of the Green New Deal Network, which promotes public support for climate justice, was similarly measured in his enthusiasm when I asked if the pause would have political upsides for Democrats in November. “A lot of the people Biden relied on to win in 2020 — it’s not clear whether they’re motivated enough to turn out again,” he told me. “Especially in BIPOC, low-income communities, and youth voters.” And while the administration’s LNG pause could be viewed as a direct appeal to such a voting bloc, Ing sees the move more as “a highlight reel played at halftime. What matters is how you play the game and right now, we don’t know the plan for the second half.”

An LNG permitting “pause” means nothing for the export terminals that are already under construction or operating. And once the pause is over, more approvals could come. For now, yes, Cameron has its hard-won reprieve. But the status quo of high cancer rates, respiratory health problems, poverty, and environmental exploitation remain unchanged for those who currently call it home.

“My children have asthma,” Ozane said, “and they’re dealing with this pollution every day.”

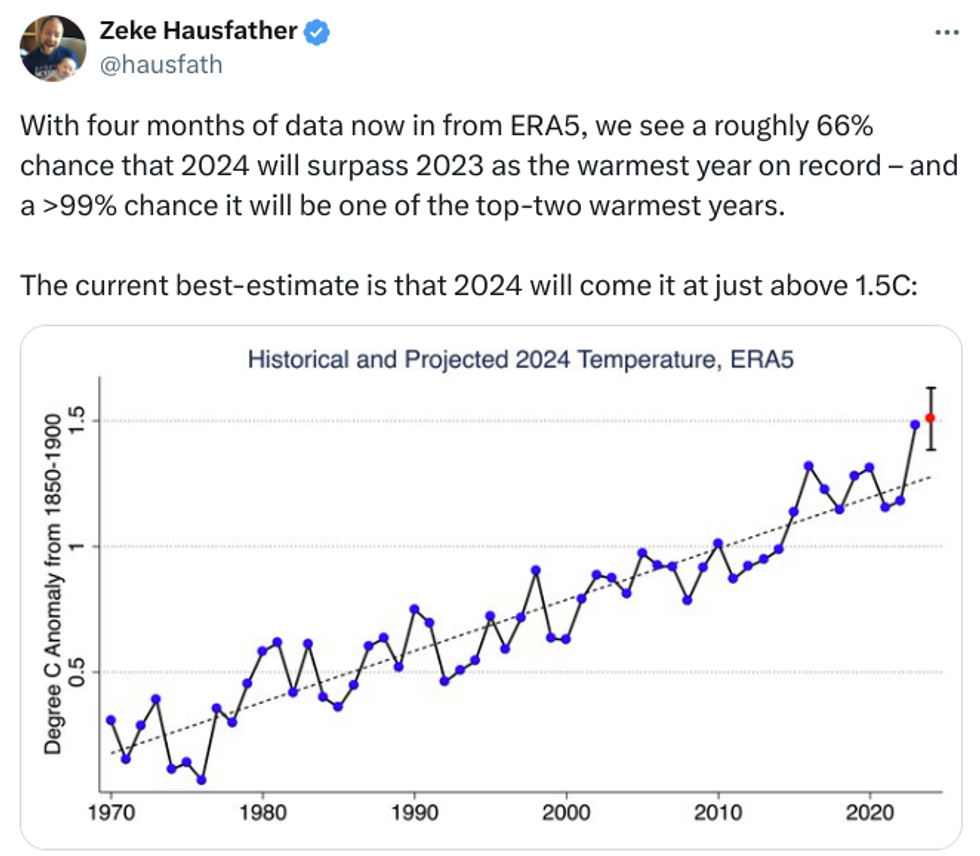

World Bank/Recipe for a Livable Planet report

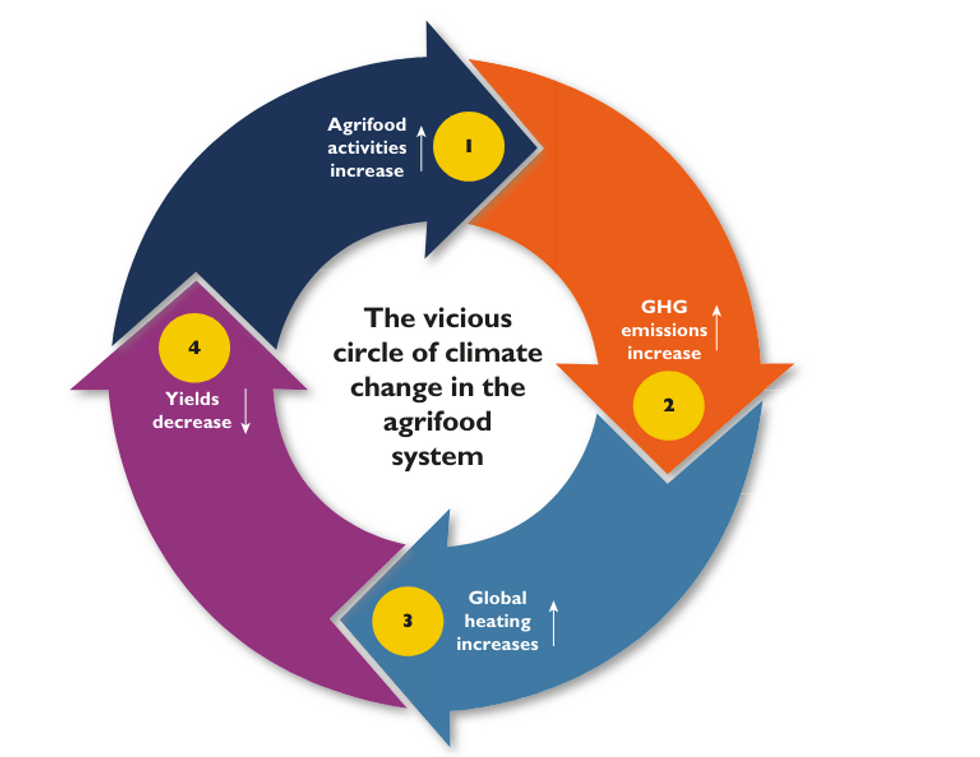

World Bank/Recipe for a Livable Planet report A flooded hospital entrance in Porto Alegre Max Peixoto/Getty Images

A flooded hospital entrance in Porto Alegre Max Peixoto/Getty Images Cypress Creek Renewables

Cypress Creek Renewables