You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

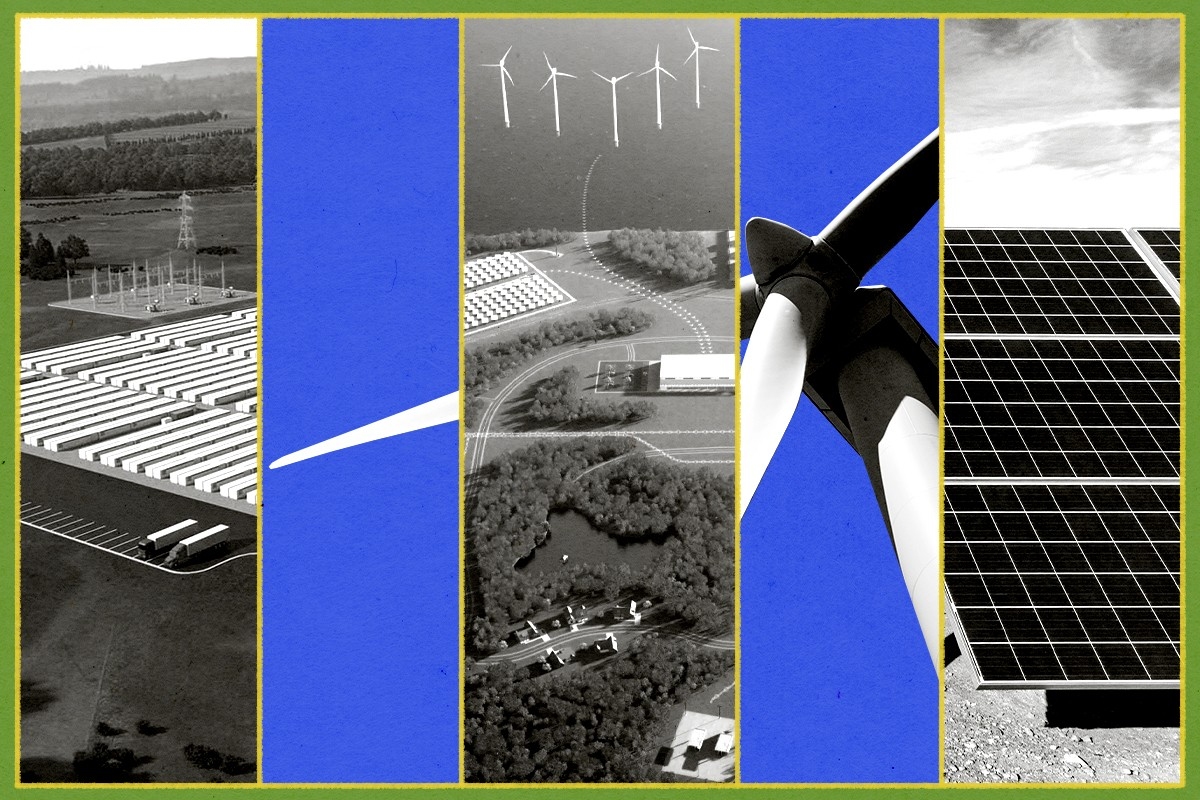

Why the grid of the future might hinge on these 10 projects.

The energy transition happens one project at a time. Cutting carbon emissions is not simply a matter of shutting down coal plants or switching to electric cars. It calls for a vast number of individual construction projects to coalesce into a whole new energy system, one that can generate, transmit, and distribute new forms of clean power. Even with the right architecture of regulations and subsidies in place, each project must still conquer a series of obstacles that can require years of planning, fundraising, and cajoling, followed by exhaustive review before they can begin building, let alone operating.

These 10 projects represent the spectrum of solutions that could enable a transition to a carbon-free energy system. The list includes vastly scaled up versions of mature technologies like wind and solar power alongside the traditional energy infrastructure necessary to move that power around. Many of the most experimental or first-of-a-kind projects on this list are competing to play the role of “clean firm” power on the grid of the future. Form’s batteries, Fervo’s geothermal plants, NET Power’s natural gas with carbon capture, and TerraPower’s molten salt nuclear reactor could each — in theory — dispatch power when it’s needed and run for as long as necessary, unconstrained by the weather. Others, like Project Cypress, are geared at solving more distant problems, like cleaning up the legacy carbon in the atmosphere.

But they do not all have a clear path to success. Each one has already faced challenges, and many of them are likely to face a great number more. We call these the make-or-break energy projects because it's still unclear what the clean energy system of the future is going to look like, but the projects from this list are likely to play a big part in it — if, that is, they get there.

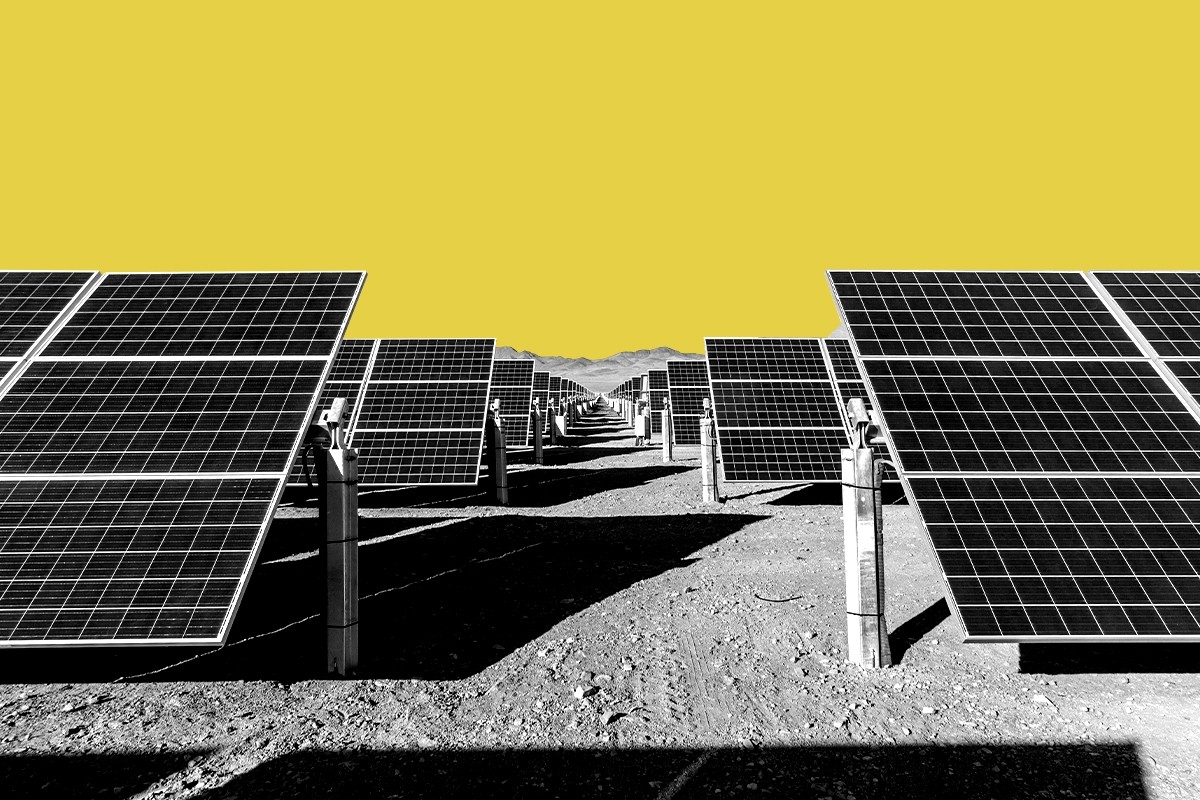

Type of project: Solar farm

Developer: Intersect Power

Location: Desert Center, Riverside County, California.

Size: 400 megawatts of generation and 650 megawatts of storage

Operation date: Possibly 2025

Cost: $990 million

Why it matters: Facing opposition from local retirees angered by the large number of projects popping up in the area, as well as from conservation-focused groups — such as Basin and Range Watch, which opposes many utility-scale energy projects in desert areas — Easley will be a test of whether California’s reforms to limit the timeframe of appeals to the state’s environmental reviews can actually work in getting a project approved and online faster.

The early signs are promising. A nearby solar project by the same developer, Intersect Power, recently went into operation after getting approved by the Bureau of Land Management in January 2022. Easley could be operational “as early as late 2025,” according to a Plan of Development prepared for Intersect Power.

Easley is also an example of what’s increasingly becoming standard in California, at both the residential and utility-scale level: pairing solar with storage. The California grid increasingly relies on batteries to keep the lights on as solar ramps up and down in the mornings and, especially, the evenings. The state has procured a massive amount of storage and has adjusted how utilities pay for rooftop solar in a way that encourages pairing battery systems with rooftop solar panels. This both stabilizes the grid and helps further decarbonize it, as batteries that are physically close to intermittent renewables are more likely to abate carbon emissions.

Type: Energy storage

Developer: Form Energy and Great River Energy

Location: Cambridge, Minnesota

Size: 150 megawatt hours

Operation date: End of 2025

Cost: Unknown; Goal of less than 1/10th cost of utility-scale lithium-ion batteries per megawatt hour

Why it matters: Form Energy first made waves in 2020 when it announced a contract with Great River Energy, a Minnesota electric utility, to build a battery that could store 100 hours’ worth of electricity, which was simply unheard of. Other energy storage companies were just trying to break the 4-hour limitation of lithium-ion, aiming for 8 hours or, at most, 12. Days-long energy storage would be a game changer for maintaining reliability during extreme weather events, storing renewable energy for stretches of cloudy days or windless nights or kicking in when demand peaks. At first, Form’s project was shrouded in mystery. How, exactly, would it do this? But a year later, the company revealed the secret chemistry behind its breakthrough: iron and oxygen. The batteries are filled with iron pellets that, when exposed to oxygen, rust, releasing electrons to the grid. They “charge” by running in reverse, using the electrical current from the grid to convert the rust back to iron.

Since then, the hype has continued to build. Form has raised nearly $1 billion from venture capital and been awarded tens of millions more ingovernment grants. It has signed contracts with six utilities to deploy projects in California, New York, Virginia, Georgia, and Colorado, in addition to Minnesota. All this, despite not having completed a single project yet.

The Great River Energy Project is set to be the first to come online. Originally, the company said it would be operating by the end of 2023; now it’s expected to start construction later this year and begin operating in early 2025, Vice President of Communications Sarah Bray told Heatmap. First, the company has to complete construction of its first factory in Weirton, West Virginia, where it will be producing all of the batteries. Bray said it expects to start high-volume production later this year.

Type: Onshore wind

Developer: Pattern Energy

Location: Lincoln, Torrance, and San Miguel Counties, New Mexico, with transmission into Arizona

Size: 3,500 megawatts

Operation date: 2026

Cost: The project’s developer, Pattern Energy, has secured $11 billion in financing for the wind and associated transmission project. The cost of the project is estimated to be $8 billion.

Why it matters: This would be the biggest wind project in the country and a test case for a variety of energy policy objectives at both the state and federal level. For California, it would be a key step in decarbonizing its grid, as the state right now imports a large amount of its power, not all of which is carbon-free. For the federal government, it meets several goals — using public lands for carbon-free energy development, plus long-distance transmission to spur energy development across the country and link clean power resources in rural areas to major load centers.

It would also mean an ambitious project could overcome long and concerted opposition. The project was first proposed in 2006, and its transmission line cleared environmental review back in 2015, but it has been mired in lawsuit after lawsuit. Most recently, a coalition of conservation groups and Indian tribes sued to halt construction on the power line portion of the project in Arizona’s San Pedro Valley, claiming that their cultural rights had not been adequately respected. In April, a judge allowed construction to continue, ruling that those claims were barred by the existing federal approvals, which had taken years to attain.

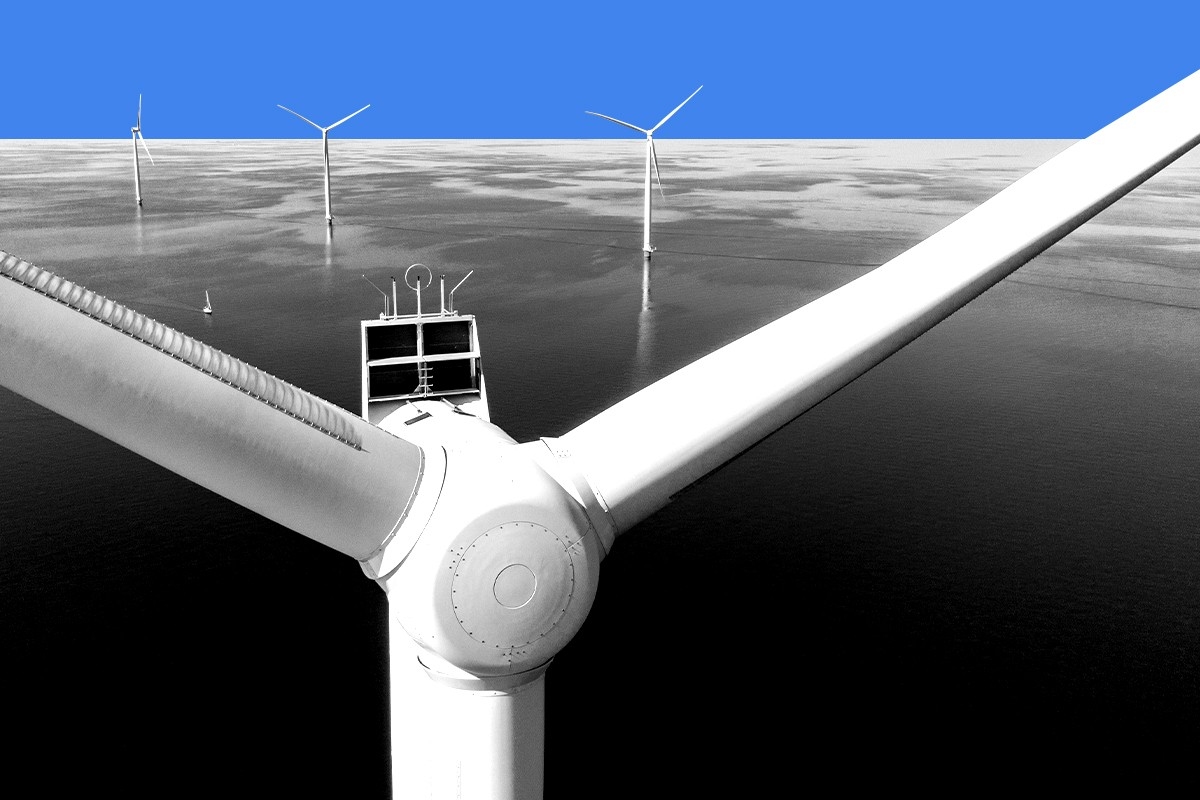

Type: Offshore wind

Developer: Equinor

Location: South of Long Island, New York

Size: 810 megawatts

Operation date: 2026

Cost: Not available, but an earlier estimate for developing two wind farms was $3 billion. Costs have since risen, but the second farm, Empire Wind 2, is no longer under contract.

Why it matters: The Northeast, and especially New York State, have aggressive aims for decarbonization, with a goal of 70% of the state’s electricity coming from renewables by 2030. The Biden administration also has a specific goal for 30 gigawatts of offshore wind capacity by 2030, and New York has a goal of 9 gigawatts by 2035. These types of high-capacity projects will be essential for the Northeast to decarbonize. The windy coast of the Atlantic Ocean is the most potent large-scale renewable resource in the region, and many of the region’s large load centers, such as New York City and Boston, are on the coast.

Offshore wind, while expensive, can present less permitting hassle and local opposition than onshore wind or utility-scale solar. Empire Wind 1 (along with Sunrise Wind) matters tremendously for New York’s offshore wind program, which has been in development for years but has faced escalating costs and project cancellations. Only one offshore wind project is actually operational in the state, South Fork Wind, which was contracted outside the NYSERDA process and has around 130 megawatts of capacity. If Empire manages to get steel in the water and electrons flowing to the coast, it will be a sign that the Northeast’s — and thus the country’s — decarbonization goals are at least somewhat attainable.

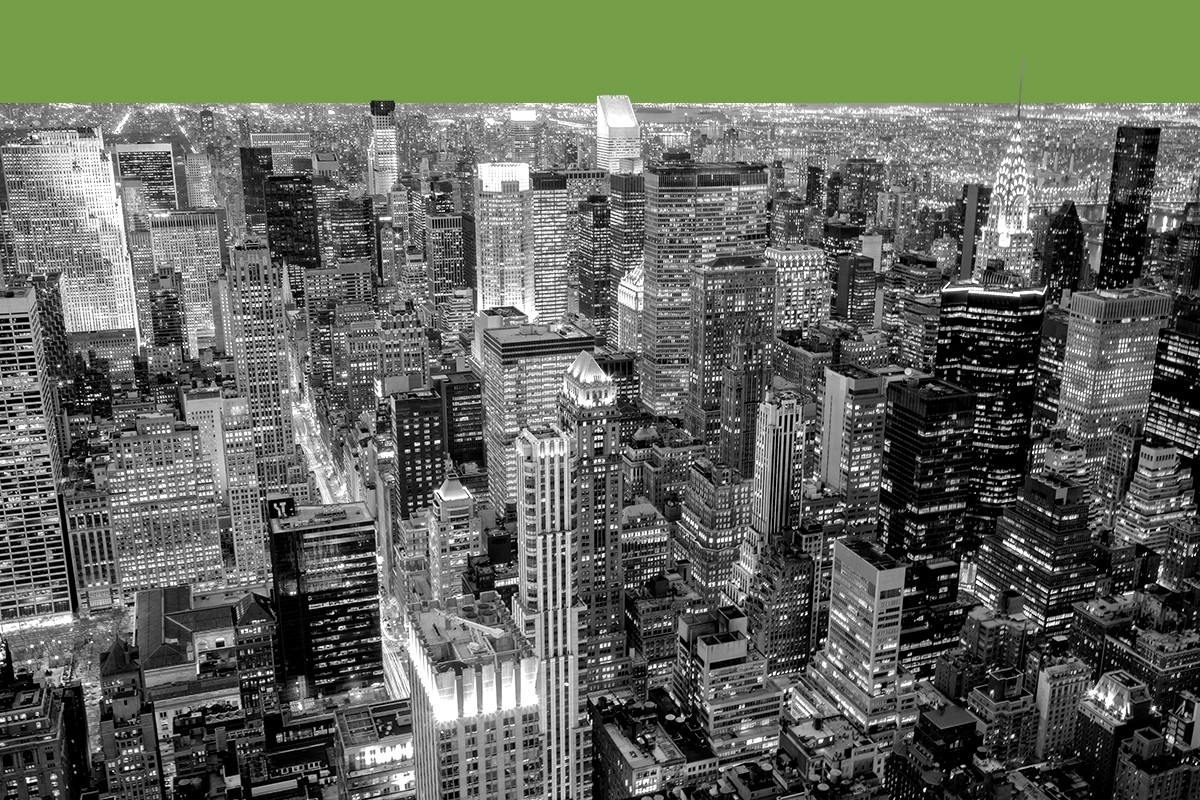

Type: Transmission

Developers: Transmission Developers, which is owned by the Blackstone Group

Size: 339 miles / 1,250 megawatts

Operation date: 2026

Cost: $6 billion

Why it matters: The Champlain Hudson Power Express, often referred to as CHPE (affectionately pronounced “chippy”) will deliver 1,250 megawatts of hydropower from Quebec into the New York City grid, which is currently about 90% powered by fossil fuels. It is “the most powerful project you’ll never see,” according to its developers, as it is the largest transmission line in the country to be installed entirely underground and underwater.

The project is essential to New York’s goal to build a zero-emission electricity system by 2040. The line will supply an always-available source of clean power to supplement intermittent wind and solar generation and maintain a reliable grid. It has already overcome a number of barriers, including nearly a decade of environmental reviews, uncertainty over whether New York would buy its power, and opposition from conservation advocates concerned about the negative impacts of hydroelectric dams on the environment and on Native communities in Canada.

When it begins operating, New Yorkers won’t just get cleaner power — they should also see air quality benefits almost immediately. The new line is expected to cut air pollution equivalent to that released by 15 of the city’s 16 fossil fuel-fired peaker plants.

Developer: Fervo

Type: Geothermal

Location: Beaver County, Utah

Size: 400 megawatts

Operation date: 2026, although the project isn’t expected to be finished until 2028

Cost: Not disclosed, but Fervo raised $244 million and said that the cash “will support Fervo’s continued operations at Cape Station.”

Why it matters: This enhanced geothermal project is not the first one for Fervo. The company’s Nevada site, Project Red, began providing power for Google data centers in Nevada in November 2023. This planned site, however, will be far bigger: Fervo currently has authorization from the Bureau of Land Management for up to 29 exploratory wells, while the Project Red site had just two. Cape Station broke ground in September 2023, and in the first six months of drilling, Fervo said it reduced costs from drilling by 70% compared to its Project Red wells.

As the grid decarbonizes and major power consumers like technology companies insist on having clean power for their operations, there will be massive and growing demand for so-called “clean firm” power, carbon-free power that is available all the time. Conventional wind and solar is intermittent, and existing battery technology only allows for limited output over time. Fervo’s “enhanced geothermal” technology uses techniques borrowed from the oil and gas industry to be able to produce geothermal power essentially anywhere where there are hot enough rocks underneath the surface of the Earth, as opposed to conventional geothermal, which depends on locating hot enough fluid or stream.

If Fervo can demonstrate that it can produce power at scale at costs comparable to existing conventional geothermal projects, it can expect a massive market for it and demand for more projects.

Type: Nuclear

Developer: TerraPower

Location: Kemmerrer, Wyoming

Size: 345 megawatts

Operation date: Not available, but the company said in 2021 that it plans to be operational “in the next seven years.” Updated to the 2024 application, that would put it on track for a 2030 completion date.

Cost: Not available, but TerraPower has raised around $1 billion and the federal government has pledged around $2 billion to support the project, which TerraPower has said it will “match … dollar for dollar.”

Why it matters: TerraPower is just one of many companies flogging designs for advanced nuclear reactors, which are smaller and promise to be cheaper to build than America’s existing light-water nuclear reactor fleet. The construction permit application the company submitted in March was a first for a commercial advanced reactor. TerraPower matters as much for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission as it does for anyone else, as it’s a test of whether the NRC can meet Congress and the White House’s preference for a more accelerated approval process for advanced nuclear power.

TerraPower’s design, if successful, would be a landmark for the American nuclear industry. The reactor design calls for cooling with liquid sodium instead of the standard water-cooling of American nuclear plants. This technique promises eventual lower construction costs because it requires less pressure than water (meaning less need for expensive safety systems) and can also store heat, turning the reactor into both a generator and an energy storage system.

While there are a number of existing advanced nuclear designs, several of which involve liquid sodium, Natrium could potentially play well with a renewable-heavy grid by providing steady, unchanging output like a current nuclear reactor as well as discharging stored energy in response to renewables falling off the grid.

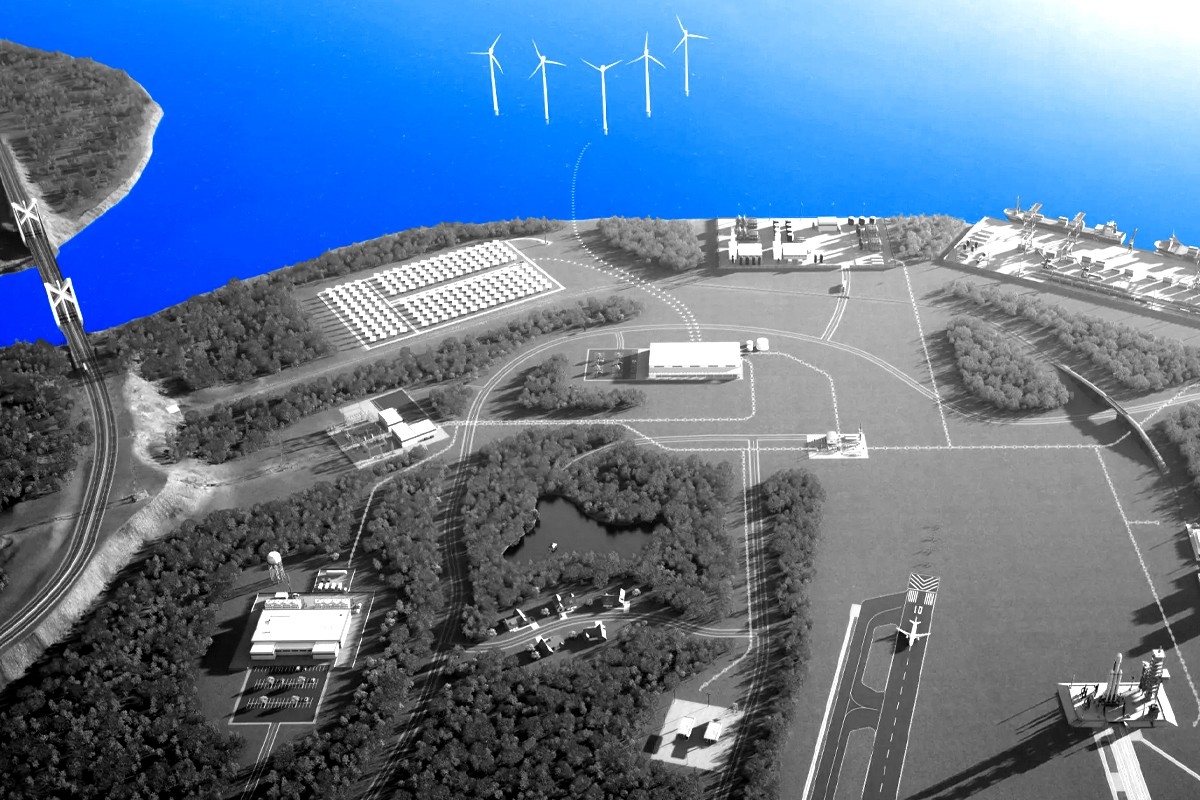

Type: Hydrogen

Developer: Hy Stor Energy

Location: Project components located throughout Mississippi, with some in Eastern Louisiana

Size: Goal of 340,000 metric tons per year (phase one)

Operation date: 2027

Cost: Initially reported as $3 billion; recently reported as more than $10 billion. (In response to an inquiry from Heatmap, the company replied that it “will be in the multiple billions of dollars.”

Why it matters: Truly carbon-free hydrogen could unlock big emissions reductions across the economy, from fertilizer production, to steelmaking, to marine shipping. But few companies are going to the lengths that Hy Stor is gto ensure its product is really clean. The company is building the first off-grid hydrogen production facility powered entirely by wind and solar. That means Hy Stor will have no problem claiming the new hydrogen production tax credit, which requires companies to match their operations with clean energy sources by the hour — a provision that’s been contested by large portions of the hydrogen industry.

For a company that has never built anything before, the scale of Hy Stor’s Mississippi project is ambitious. The company has acquired about 70,000 acres across Mississippi and Louisiana, along with 10 underground salt domes — mounds of salt buried beneath the Earth’s surface that can be dissolved to form cavernous, skyscraper-sized storage facilities for hydrogen. Those salt domes are the key to Hy Stor’s approach, and what enables the company to rely on intermittent renewables. By storing vast amounts of hydrogen, the company will be able to deliver a steady supply to customers and will also have a backup source of energy for its own operations when wind and solar are less available.

Chief Commercial Officer Claire Behar told Heatmap the company has obtained many of the necessary permits, including for its salt caverns and the plant’s water use. It plans to begin construction at the beginning of 2025, and to have the first phase of the project “in service at scale” by 2027. Hy Stor recently announced a deal to purchase its electrolyzers, devices that split water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen, from a Norwegian company called Nel Hydrogen. It has also signed up a few customers, including a local port and a green steel company.

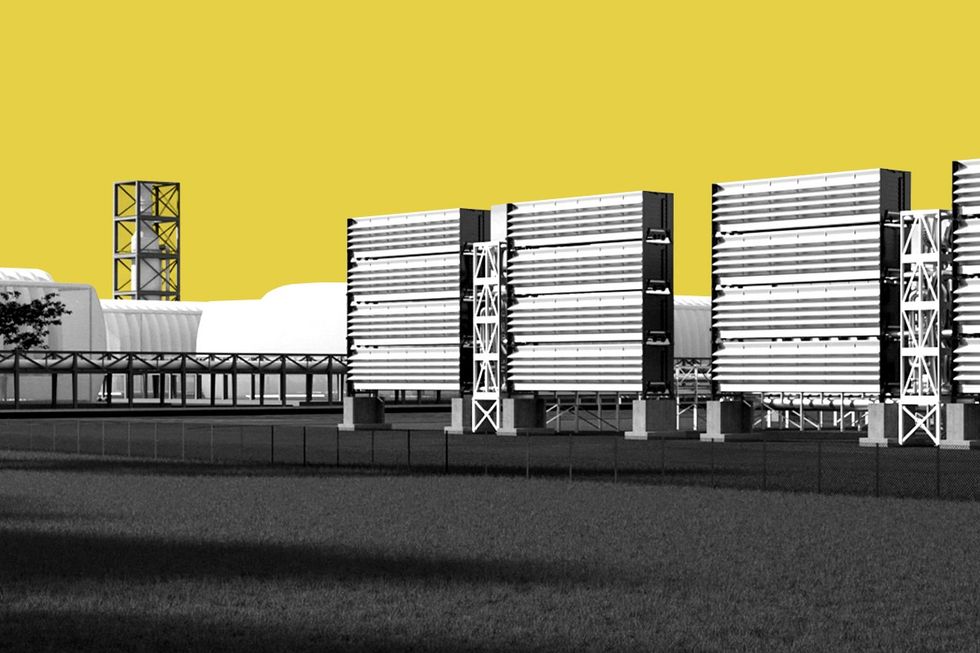

Type: Carbon removal

Developers: Climeworks, Heirloom, and Battelle

Location: Calcasieu Parish, Louisiana

Size: Goal of capturing 1 million metric tons per year

Operation date: About 2030

Cost: Total project cost unknown; eligible for up to $600 million from the Department of Energy for its Regional Direct Air Capture Hubs Program.

Why it matters: Project Cypress might be the most ambitious project to remove carbon from the atmosphere under development in the world. It is a collaboration by two leading direct air capture companies, Heirloom Carbon Technologies and Climeworks, which were among the first to demonstrate their ability to capture carbon directly from the air and store it at commercial scale. Now, the two will be attempting to scale up exponentially, from capturing a few thousands tons per year to a combined million.

Last August, the Department of Energy selected Project Cypress to be one of four direct air capture hubs it will support with $3.5 billion from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. In March, the project was awarded its first infusion of $50 million, but the developers will have to do extensive community engagement to continue receiving funding. Battelle, the project developer, told Heatmap the project has also received an additional $51 million in private investment.

Between financing, permitting challenges, renewable energy sourcing, and community opposition, the project is sure to face a bumpy road ahead. The project and its developers have no ties to the oil and gas industry, but that hasn’t done much to win over the support of environmental justice advocates, who see the project as a dangerous distraction from cutting emissions and pollution in Louisiana. But if Project Cypress is successful, it will show the world what direct air capture looks like at climate-relevant scales.

Type: Carbon capture

Developer: NET Power

Location: Ector County, Texas

Size: 300 megawatts

Operation date: Late 2027 or early 2028

Cost: About $1 billion

Why it matters: Oil and gas CEOs love to say that the problem is not fossil fuels, the problem is emissions. NET Power’s technology — a natural gas power plant with zero emissions, carbon or otherwise — could prove to be the ultimate vindication of that statement. In short, NET Power’s system recycles most of the CO2 it produces and uses it to generate more energy. It also utilizes pure oxygen, unlike typical natural gas plants that take in regular air, which is mostly nitrogen. This means that any remaining CO2 not recycled in the plant is relatively pure and easy to capture.

NET Power opened a 50 megawatt demonstration plant in La Porte, Texas, in 2018, and is developing a 300 megawatt commercial plant in Ector County, Texas, in partnership with Occidental Petroleum, Baker Hughes, and Constellation Energy. On a recent earnings call, CEO Danny Rice said the project was “expected to have a lower levelized cost per kilowatt hour than new nuclear, new geothermal, and new hydro.”

The company generated a lot of excitement among energy experts in the fall of 2021 when it announced that its La Porte project had successfully delivered power to the Texas grid. It also raised a lot of money when it went public last summer. But things have been somewhat rocky since. During a December earnings call, NET Power’s president told investors that its first commercial plant would be delayed by at least a year due to supply chain challenges. According to filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission, the company also applied for funding from the Department of Energy’s Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations last year, but was not selected. It has not yet found any third parties to license its technology or offtakers to buy energy from the Ector County plant, and noted in its recent filings that while the La Porte pilot project delivered electricity to the grid, it did not, in fact, deliver “net” power — meaning that it used more power than it generated.

A spokesperson for the company told Heatmap the La Porte facility was solely intended to “prove the technical viability of the NET Power Cycle” and not intended to produce net power. So everything’s now riding on Project Permian.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct a typographical error in the amount of private investment Project Cypress has received.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

It’s either reassure investors now or reassure voters later.

Investor-owned utilities are a funny type of company. On the one hand, they answer to their shareholders, who expect growing returns and steady dividends. But those returns are the outcome of an explicitly political process — negotiations with state regulators who approve the utilities’ requests to raise rates and to make investments, on which utilities earn a rate of return that also must be approved by regulators.

Utilities have been requesting a lot of rate increases — some $31 billion in 2025, according to the energy policy group PowerLines, more than double the amount requested the year before. At the same time, those rate increases have helped push electricity prices up over 6% in the last year, while overall prices rose just 2.4%.

Unsurprisingly, people have noticed, and unsurprisingly, politicians have responded. (After all, voters are most likely to blame electric utilities and state governments for rising electricity prices, Heatmap polling has found.) Democrat Mikie Sherrill, for instance, won the New Jersey governorship on the back of her proposal to freeze rates in the state, which has seen some of the country’s largest rate increases.

This puts utilities in an awkward position. They need to boast about earnings growth to their shareholders while also convincing Wall Street that they can avoid becoming punching bags in state capitols.

Make no mistake, the past year has been good for these companies and their shareholders. Utilities in the S&P 500 outperformed the market as a whole, and had largely good news to tell investors in the past few weeks as they reported their fourth quarter and full-year earnings. Still, many utility executives spent quite a bit of time on their most recent earnings calls talking about how committed they are to affordability.

When Exelon — which owns several utilities in PJM Interconnection, the country’s largest grid and ground zero for upset over the influx data centers and rising rates — trumpeted its growing rate base, CEO Calvin Butler argued that this “steady performance is a direct result of a continued focus on affordability.”

But, a Wells Fargo analyst cautioned, there is a growing number of “affordability things out there,” as they put it, “whether you are looking at Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware.” To name just one, Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro said in a speech earlier this month that investor-owned utilities “make billions of dollars every year … with too little public accountability or transparency.” Pennsylvania’s Exelon-owned utility, PECO, won approval at the end of 2024 to hike rates by 10%.

When asked specifically about its regulatory strategy in Pennsylvania and when it intended to file a new rate case, Butler said that, “with affordability front and center in all of our jurisdictions, we lean into that first,” but cautioned that “we also recognize that we have to maintain a reliable and resilient grid.” In other words, Exelon knows that it’s under the microscope from the public.

Butler went on to neatly lay out the dilemma for utilities: “Everything centers on affordability and maintaining a reliable system,” he said. Or to put it slightly differently: Rate increases are justified by bolstering reliability, but they’re often opposed by the public because of how they impact affordability.

Of the large investor-owned utilities, it was probably Duke Energy, which owns electrical utilities in the Carolinas, Florida, Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio, that had to most carefully navigate the politics of higher rates, assuring Wall Street over and over how committed it was to affordability. “We will never waver on our commitment to value and affordability,” Duke chief executive Harry Sideris said on the company’s February 10 earnings call.

In November, Duke requested a $1.7 billion revenue increase over the course of 2027 and 2028 for two North Carolina utilities, Duke Energy Carolinas and Duke Energy Progress — a 15% hike. The typical residential customer Duke Energy Carolinas customer would see $17.22 added onto their monthly bill in 2027, while Duke Energy Progress ratepayers would be responsible for $23.11 more, with smaller increases in 2028.

These rate cases come “amid acute affordability scrutiny, making regulatory outcomes the decisive variable for the earnings trajectory,” Julien Dumoulin-Smith, an analyst at Jefferies, wrote in a note to clients. In other words, in order to continue to grow earnings, Duke needs to convince regulators and a skeptical public that the rate increases are necessary.

“Our customers remain our top priority, and we will never waver on our commitment to value and affordability,” Sideris told investors. “We continue to challenge ourselves to find new ways to deliver affordable energy for our customers.”

All in all, “affordability” and “affordable” came up 15 times on the call. A year earlier, they came up just three times.

When asked by a Jefferies analyst about how Duke could hit its forecasted earnings growth through 2029, Sideris zeroed in on the regulatory side: “We are very confident in our regulatory outcomes,” he said.

At the same time, Duke told investors that it planned to increase its five-year capital spending plan to $103 billion — “the largest fully regulated capital plan in the industry,” Sideris said.

As far as utilities are concerned, with their multiyear planning and spending cycles, we are only at the beginning of the affordability story.

“The 2026 utility narrative is shifting from ‘capex growth at all costs’ to ‘capex growth with a customer permission slip,’” Dumoulin-Smith wrote in a separate note on Thursday. “We believe it is no longer enough for utilities to say they care about affordability; regulators and investors are demanding proof of proactive behavior.”

If they can’t come up with answers that satisfy their investors, ultimately they’ll have to answer to the voters. Last fall, two Republican utility regulators in Georgia lost their reelection bids by huge margins thanks in part to a backlash over years of rate increases they’d approved.

“Especially as the November 2026 elections approach, utilities that fail to demonstrate concrete mitigants face political and reputational risk and may warrant a credibility discount in valuations, in our view,” Dumoulin wrote.

At the same time, utilities are dealing with increased demand for electricity, which almost necessarily means making more investments to better serve that new load, which can in the short turn translate to higher prices. While large technology companies and the White House are making public commitments to shield existing customers from higher costs, utility rates are determined in rate cases, not in press releases.

“As the issue of rising utility bills has become a greater economic and political concern, investors are paying attention,” Charles Hua, the founder and executive director of PowerLines, told me. “Rising utility bills are impacting the investor landscape just as they have reshaped the political landscape.”

Plus more of the week’s top fights in data centers and clean energy.

1. Osage County, Kansas – A wind project years in the making is dead — finally.

2. Franklin County, Missouri – Hundreds of Franklin County residents showed up to a public meeting this week to hear about a $16 billion data center proposed in Pacific, Missouri, only for the city’s planning commission to announce that the issue had been tabled because the developer still hadn’t finalized its funding agreement.

3. Hood County, Texas – Officials in this Texas County voted for the second time this month to reject a moratorium on data centers, citing the risk of litigation.

4. Nantucket County, Massachusetts – On the bright side, one of the nation’s most beleaguered wind projects appears ready to be completed any day now.

Talking with Climate Power senior advisor Jesse Lee.

For this week's Q&A I hopped on the phone with Jesse Lee, a senior advisor at the strategic communications organization Climate Power. Last week, his team released new polling showing that while voters oppose the construction of data centers powered by fossil fuels by a 16-point margin, that flips to a 25-point margin of support when the hypothetical data centers are powered by renewable energy sources instead.

I was eager to speak with Lee because of Heatmap’s own polling on this issue, as well as President Trump’s State of the Union this week, in which he pitched Americans on his negotiations with tech companies to provide their own power for data centers. Our conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What does your research and polling show when it comes to the tension between data centers, renewable energy development, and affordability?

The huge spike in utility bills under Trump has shaken up how people perceive clean energy and data centers. But it’s gone in two separate directions. They see data centers as a cause of high utility prices, one that’s either already taken effect or is coming to town when a new data center is being built. At the same time, we’ve seen rising support for clean energy.

As we’ve seen in our own polling, nobody is coming out looking golden with the public amidst these utility bill hikes — not Republicans, not Democrats, and certainly not oil and gas executives or data center developers. But clean energy comes out positive; it’s viewed as part of the solution here. And we’ve seen that even in recent MAGA polls — Kellyanne Conway had one; Fabrizio, Lee & Associates had one; and both showed positive support for large-scale solar even among Republicans and MAGA voters. And it’s way high once it’s established that they’d be built here in America.

A year or two ago, if you went to a town hall about a new potential solar project along the highway, it was fertile ground for astroturf folks to come in and spread flies around. There wasn’t much on the other side — maybe there was some talk about local jobs, but unemployment was really low, so it didn’t feel super salient. Now there’s an energy affordability crisis; utility bills had been stable for 20 years, but suddenly they’re not. And I think if you go to the town hall and there’s one person spewing political talking points that they've been fed, and then there’s somebody who says, “Hey, man, my utility bills are out of control, and we have to do something about it,” that’s the person who’s going to win out.

The polling you’ve released shows that 52% of people oppose data center construction altogether, but that there’s more limited local awareness: Only 45% have heard about data center construction in their own communities. What’s happening here?

There’s been a fair amount of coverage of [data center construction] in the press, but it’s definitely been playing catch-up with the electric energy the story has on social media. I think many in the press are not even aware of the fiasco in Memphis over Elon Musk’s natural gas plant. But people have seen the visuals. I mean, imagine a little farmhouse that somebody bought, and there’s a giant, 5-mile-long building full of computers next to it. It’s got an almost dystopian feel to it. And then you hear that the building is using more electricity than New York City.

The big takeaway of the poll for me is that coal and natural gas are an anchor on any data center project, and reinforce the worst fears about it. What you see is that when you attach clean energy [to a data center project], it actually brings them above the majority of support. It’s not just paranoia: We are seeing the effects on utility rates and on air pollution — there was a big study just two days ago on the effects of air pollution from data centers. This is something that people in rural, urban, or suburban communities are hearing about.

Do you see a difference in your polling between natural gas-powered and coal-powered data centers? In our own research, coal is incredibly unpopular, but voters seem more positive about natural gas. I wonder if that narrows the gap.

I think if you polled them individually, you would see some distinction there. But again, things like the Elon Musk fiasco in Memphis have circulated, and people are aware of the sheer volume of power being demanded. Coal is about the dirtiest possible way you can do it. But if it’s natural gas, and it’s next door all the time just to power these computers — that’s not going to be welcome to people.

I'm sure if you disentangle it, you’d see some distinction, but I also think it might not be that much. I’ll put it this way: If you look at the default opposition to data centers coming to town, it’s not actually that different from just the coal and gas numbers. Coal and gas reinforce the default opposition. The big difference is when you have clean energy — that bumps it up a lot. But if you say, “It’s a data center, but what if it were powered by natural gas?” I don’t think that would get anybody excited or change their opinion in a positive way.

Transparency with local communities is key when it comes to questions of renewable buildout, affordability, and powering data centers. What is the message you want to leave people with about Climate Power’s research in this area?

Contrary to this dystopian vision of power, people do have control over their own destinies here. If people speak out and demand that data centers be powered by clean energy, they can get those data centers to commit to it. In the end, there’s going to be a squeeze, and something is going to have to give in terms of Trump having his foot on the back of clean energy — I think something will give.

Demand transparency in terms of what kind of pollution to expect. Demand transparency in terms of what kind of power there’s going to be, and if it’s not going to be clean energy, people are understandably going to oppose it and make their voices heard.