Today, Silver City is a ghost town, and Leslie’s grisly demise is relegated to a single sentence on a Bureau of Land Management sign lining the way down to a boat ramp that passing F-150s don’t bother braking to read. But the tremendous power and possibility of the Owyhee watershed has never been less in dispute — or, perhaps, more in jeopardy.

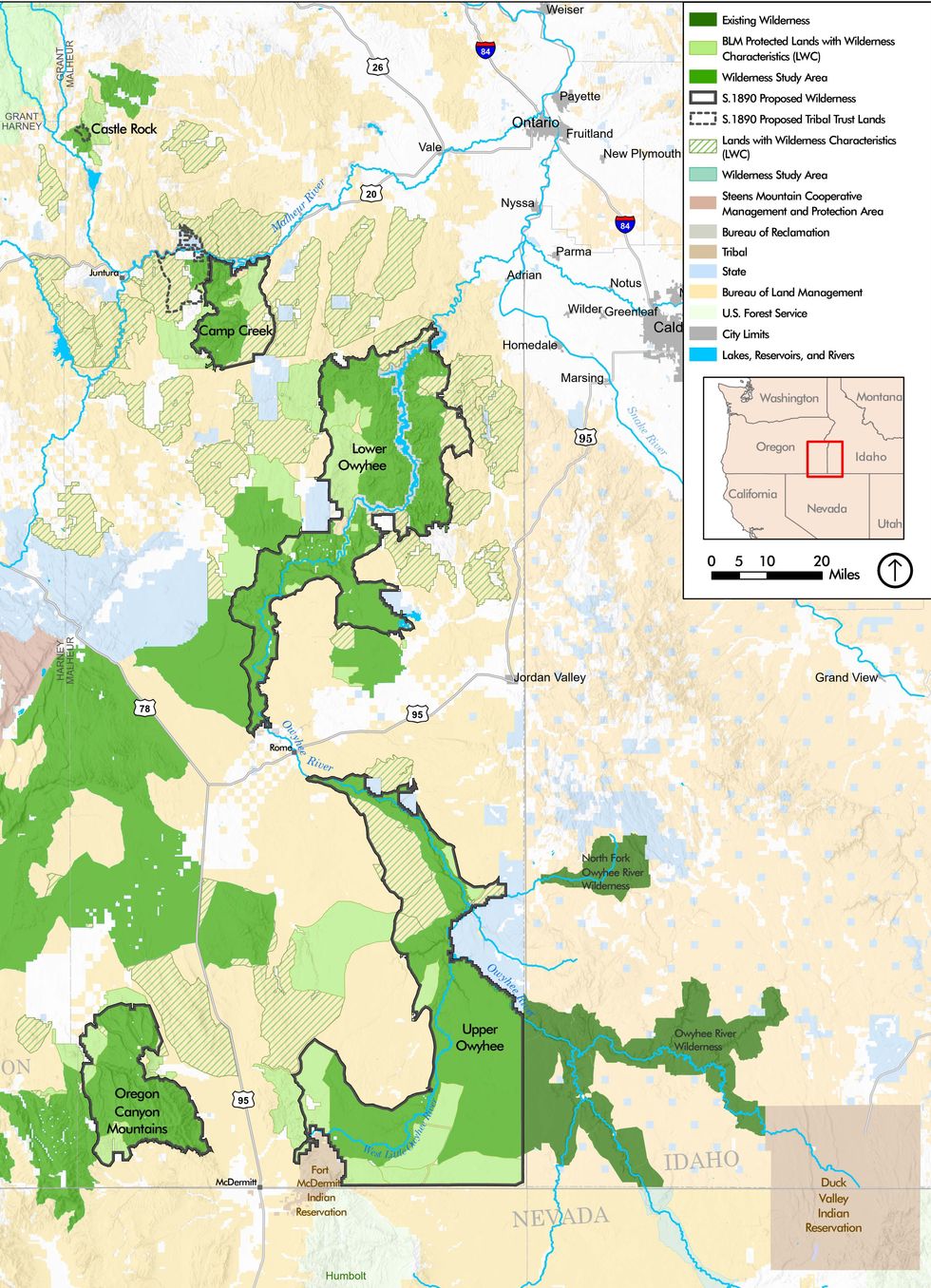

The Owyhee (pronounced “oh-why-hee,” an old spelling of “Hawaii” in honor of more doomed explorers) is a 7 million-acre ecoregion that runs through Oregon’s southeasternmost county, Malheur, though it spreads as far east as Idaho and as far south as Nevada. On Google Maps, it looks like a big blank space; the core of the Canyonlands is crossed by just three paved roads. In fact, it’s the largest undeveloped region left in the Lower 48. On a resource management map, the area reveals itself to be a complicated patchwork of BLM, tribal, state, Forest Service, and privately owned lands, as well as a smattering of quasi-protected “Wilderness Study Areas” and “Land with Wilderness Characteristics” that exist at the whims of Congress. The region contains many of the materials and geographic features necessary for the clean energy transition, making one of the most pristine regions in the state also potentially one of its most productive.

But it can’t be both.

In person, it’s easy to see why the area has excited developers. Towering river canyons inspire dreams of pumped storage hydropower. There has been talk of constructing a second geothermal plant in the area, and uranium mining has intermittently returned to the conversation. Gold and silver claims stud the hillsides, a testament to the presence of metals that, amongst other things, are used for making electric vehicle circuit boards and solar panels. Draw a line through the region’s gentler northern sagelands and you’ve plotted the proposed, much-needed Boardman-to-Hemingway transmission route to bring hydropower from Washington state to Boise, one of the fastest-growing cities in the nation. And just outside the Owyhee watershed, to the west, is the upper edge of the McDermitt Caldera, a shockingly remote volcanic depression where there is said to be enough concentrated lithium to build 40 million electric vehicles.

Even Leslie Gulch, with its weekend crowds from Boise and recent Instagram Reels virality, is “quietly open to mining,” Ryan Houston, the Bend-based executive director of the Oregon Natural Desert Association, told me when I met him in the Canyonlands last month.

Courtesy of the Oregon Natural Desert Association.

Courtesy of the Oregon Natural Desert Association.

Amid all this frenzy, Oregon Senators Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley, local Shoshone-Paiute tribal leaders, and a large coalition of regional and national conservation groups are working to close off 1.1 million acres of the most ecologically important land to the development nipping at its edges. Their hope is that Congress will designate four “units” in Malheur County, including the upper and lower Owyhee, as a single federally protected wilderness area — a pipe dream, given the partisan dysfunction of the current House of Representatives. The more realistic alternative is for President Biden to swoop in with the Antiquities Act and make it a new national monument.

Such an action would be in keeping with Biden’s 30x30 executive order to conserve 30% of U.S. land and water by 2030. It could also be perceived as clipping the wings of the kinds of clean energy projects his administration has proudly touted and funded.

Potential land-use conflicts like these are part of why conservation goals and the current green building movement are often portrayed as incompatible, or at least in tension. But “conservation and clean energy build-out aren’t necessarily opposing forces,” Veronica Ung-Kono, an attorney and clean energy transmission policy specialist at the National Wilderness Federation, told me. “They’re just forces that have to figure out how to interact with each other in a way that makes sense.”

No one is more aware of this than the campaigners I spoke with in Oregon. “For us as an organization, something we’re pushing ourselves on is, ‘How do we say yes to where solar and wind should be?’ Rather than just, ‘No, not there, not there, not there,’” Houston, the organizer at ONDA, which is helping to manage the monument campaign, said by way of example. Later, he told me that by setting aside 1.1 million acres for an Owyhee Monument, the conservationists essentially say that the remaining 75% of the local BLM district is open for all other possible uses.

“We’re not closing off vast swaths of the high desert to renewable energy,” he said. “What we’re doing is protecting the best of the best, so we can focus on other types of development — like renewable energy or off-road-vehicle play areas — in places where it’s most appropriate.”

To better understand the land-use issues in Malheur County, I traveled to Boise last month to attend what’s called a lek, when sage grouse gather to perform their mating rituals. The visit was organized by the NWF, which is supporting the monument push with ONDA. On the appointed day, I left my airport hotel at 3:30 a.m., crossed the state line on a two-lane highway during what I later learned was the height of mule deer migration season, and followed a poorly marked gravel road literally off the map on my phone (which, for good measure, had no reception).

It was so dark in the Owyhee that I felt more like I was rattling across the bottom of the ocean than an actual terrestrial landscape. I repeatedly mistook the full moon for oncoming headlights whenever it briefly appeared from behind the hills, and at random intervals, my car would drop into shallow streams I didn’t see coming until I was already in them. As I approached Succor Creek Campground, the designated meeting spot, I became aware that I was being hemmed in by canyon walls — perceptible only as a blackness even blacker than that of the night sky. When I finally spotted the headlamp of Aaron Kindle, NWF’s director of sporting advocacy, my overriding sense of the Owyhee Canyonlands was that they were bumpy.

Needless to say, I had absolutely no idea at the time that I had driven directly beneath what might one day become the Boardman-to-Hemingway transmission line.

The B2H, as it’s known, would be a nearly 300-mile, 500-kilovolt interstate line to send hydroelectric power generated in Washington State down to Boise. The project has become a textbook example of the permitting woes facing transmission projects in America, however. “By the time we build this, B2H is not only going to be old enough to vote, it’s going to be old enough to go to a bar and have a drink,” Adam Richins, the senior vice president and chief operating officer of Idaho Power, the electric utility that serves southern Idaho and eastern Oregon, told me.

Richins likes to joke, but the B2H’s halting progress makes him weary. More than 18 years of environmental reviews, permitting revisions, archeological and cultural studies, siting headaches, and landowner protests have plagued the planning and implementation of the transmission line, which Idaho Power owns jointly with another northwest utility, PacifiCorp. (Set to break ground this fall, B2H recently stalled again due to a scandal involving an affiliated consulting firm’s work on an unrelated project.) Originally conceived as a way to help Idaho Power meet its clean-energy goals during the summer and winter peaks that follow the region’s agricultural calendar, “I will say now that if we don’t get some of these transmission lines permitted on time, it’s possible we’re going to have to look at other resources such as natural gas,” Richins said.

Though some early plans for the B2H would have seen it cut straight through the boundaries of a future Owyhee monument, the current proposal keeps the transmission path safely outside the existing Wilderness Study Areas that surround Lake Owyhee, the reservoir at the center of what could become the “Lower Owyhee Unit.” (Somewhat confusingly, the Owyhee River flows north into the Snake River, meaning its “upper” watershed is actually to the south.)

That’s not a coincidence. The monument proposal almost entirely consists of parcels pre-designated as Lands with Wilderness Characteristics and Wilderness Study Areas, both of which are managed by the BLM and exist in a kind of limbo until Congress decides what to do with them. “If you’re a developer of solar, wind, pump storage, whatever, you’re not going to put your project in an area that’s in a quasi-protected status because that makes it extremely hard to develop,” Houston said. In other words, it’s not that the monument boundaries were drawn to avoid projects like the B2H; they were drawn to “protect the most important areas, and the most important areas have been in this quasi-slash-temporary protected status for a long time.”

Still, the transmission lines wouldn’t be entirely out of sight. The planned B2H route crosses close to the scenic northern mouth of the Owyhee Canyon before it makes its southeast turn toward Succor Creek and the Idaho border, where I’d driven across its path. More to the point, any future monument designation would mean that if permitting reform actually happens and America begins a transmission-building boom, power lines connecting the various substations of the Northwest would have to go around it, requiring diversions of 50 miles or more. Richins told me that as far as Idaho Power goes, though, “I haven’t seen anything [in the monument proposal] that has made me overly concerned.”

So far, Biden’s team hasn’t given any indication of its thinking about an Owyhee Monument, even as it has picked up the pace on conservation efforts elsewhere. Eight other national monument campaigns are also competing for attention from a friendly administration that is by no means guaranteed to remain in office next year; these include efforts to conserve California’s Chuckwalla, which would create a contiguous wildlife corridor between Joshua Tree National Park and the Kofa National Wildlife Refuge, and Colorado’s Dolores Canyons, which have both ecological and Indigenous cultural importance. “We have shared with [the administration] our binder of support and all of our petition signatures — we’ve got like 50,000 petition signatures, and hundreds and hundreds of letters — and they have said, ‘Thank you, the Owyhee is on our radar, we’ve known about it for a long time, we are tracking it, we are following it,’” said Houston.

There were rumors in the conservation community before Biden expanded two California monuments just a couple of weeks ago, meaning Owyhee organizers might get a tip-off if or when the administration makes up its mind. But November draws closer every day, and the grapevine has stayed silent. Still, after previously thwarted attempts to protect the Owyhee in 2016, 2019, and 2022, organizers think they’ve negotiated a workable compromise: The monument proposal as it currently stands is less than half the size of an earlier, more contiguous 2.5-million-acre proposal Houston and other conservationists preferred. But it also means that much more land is available for green development.

Even some of the more controversial renewable energy projects in the area have been able to move forward. On the lone stretch of shoreline on Lake Owyhee that doesn’t fall within the monument proposal, Utah-based developers are exploring the construction of a pumped storage hydropower facility. Proponents say the technology is a solution for the intermittency concerns of solar and wind since the facilities pump water from a lower reservoir to a higher one during off-peak hours, then release the water to spin turbines and generate electricity during times of high demand — effectively, a kind of massive hydroelectric battery.

Pumped storage projects require very particular geographic conditions, namely steep slopes of 1,000 feet or more, to give the water enough gravitational potential energy to work. “You have to choose your sites carefully — there are bad places to propose doing pumped storage and there are great places,” Matthew Shapiro, the CEO of rPlus Hydro, the company behind the exploration project, told me.

Lake Owyhee, with its high plateaus, is one of 11 promising sites across the country rPlus Hydro has picked out. “We were looking at a site with about 1,600 feet of vertical drop and a very large existing lower reservoir, meaning we would only have to build an upper,” Shapiro said. The proximity to the existing Midpoint-Hemingway-Summer Line and the future Boardman-Hemingway line is also appealing since it would mean rPlus Hydro would only have to build a short transmission line from the site.

There are environmental concerns about pumped storage, including its possible effect on trout below the Owyhee Dam (which, despite being a Hoover Dam prototype when it was built in 1932, does not produce hydroelectricity but instead stores water for the local irrigation district). While there might be petitions, protests, and siting issues yet, rPlus Hydro’s pumped storage project will “do whatever it does entirely independent” of the Owyhee monument protection efforts, Houston said.

Other strange alliances abound. The local ranching community, for one, is largely on board with the Owyhee Monument proposal — a minor miracle given that this corner of Oregon is also home to the wildlife refuge that was infamously occupied for 41 days by the Bundy brothers in 2016. The current monument proposal intentionally excludes any lands that would have overflowed into the more combative neighboring jurisdiction, where conservation efforts might have ignited a national-headline-making backlash.

“We don’t want the ranchers to be so pissed off that the first thing they do is go to the Trump administration” to appeal for a reversal, Houston said. The Owyhee monument is designed, in other words, to fly under the radar, lest it become another political tennis ball ricocheting between presidents like Bears Ears.

It’s designed to fly under the radar when it comes to clean energy projects, too. Houston and others were adamant that they don’t oppose the projects encircling the core conservation area — climate change, after all, is one of the biggest threats to the Owyhee, which is one of the fastest warming places in the entire county. Still, it was clear in conversations that the proposals are also spurring some of their urgency. “It’s about protecting what you have left,” is how Kindle, the NWF advocate I met at the Succor Creek Campground, put it to me.

More to the point, Houston told me that the lithium mining abutting what would become the Owyhee Monument’s westernmost unit, Oregon Canyon Mountains, is “a reminder of what can happen” if conservationists don’t act fast enough.

“You can see he is missing like four tail feathers. That one must be a fighter — and got his ass kicked.” Skyler Vold, an Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife employee with the delightful title of “sage-grouse conservation coordinator,” stepped aside from the scope so I could check out the avian incarnation of Rocky Balboa.

The light was finally coming up over the Owyhee, but it was still so cold that my toes were starting to numb in my boots. That wasn’t what had my attention, though: At one point, Vold counted nearlytwo dozensage grouse, all thumping away in the low point between two hills where they’d gathered for the lek. Kindle also spotted a lone elk on a faraway hillside, and we later heard the call of a sandhill crane, but the funny little birds with their spiky agave-leaf tails had us all enraptured.

No single creature better encapsulates the land-use fights in the West than the sage grouse. In 2018, the Trump administration stripped the birds of protections in order to open 9 million acres of the McDermitt Caldera to drilling and mining — mainly for lithium. While the Biden administration is considering new protections for sage grouse, of which there are only about 800,000 left and for whom the caldera is prime habitat, it has also dumped money into building up a domestic lithium supply chain. Sourcing lithium at home, however, will likely require access to McDermitt’s deposits.

Much of the caldera is located in Nevada, but the top rim bumps up into Oregon. It’s in this northernmost crescent that the Australian company Jindalee is considering opening its lithium mine. While the team told me it is still many years (and many environmental reviews) away from actually breaking ground, Jindalee’s executives also stressed that they see themselves as a critical player in America’s clean energy future if or when they do so.

“There’s a huge elephant in the room, which is: Where’s this lithium supply going to come from?” Ian Rodger, the Jindalee Lithium CEO, told me. The answer so far has been mainly from China, where lithium is “processed under really different social and environmental standards,” he said. “Our aspiration for the [Oregon] project is to develop it in the most responsible way.”

Simon Jowitt, an economic geologist at the University of Nevada, Reno, told me Rodger’s argument has a lot of merit. Social and environmental conditions are indeed “a lot better here than they would be in other countries,” he said, meaning that if we don’t extract the metals and minerals we’re going to use anyway locally, “then what we’re doing is we’re shipping problems away elsewhere.” There is ongoing discussion and division in the local Paiute and Shoshone Tribe about the economic and environmental pros and cons of mining near their community, as well.

The fact remains, however, that “as a human race, we need these metals and minerals if we want to do something meaningful about climate change mitigation,” Jowitt added. That requires stomaching a potentially sizeable physical footprint, especially in the case of lithium mining.

“If we are all going to go to electric vehicles by 2050,” Jowitt said, then that’s great — but policymakers and the public also “need to realize that there’s a mineral cost of this.”

Conservationists are quick to point out that mining laws in the U.S. — which have barely changed since Hiriam Leslie’s time — are stacked so in favor of the claimants that there is often no chance to get a word in edgewise. “Mining sure as heck trumps a funny chicken that goes ‘womp womp,’” is how Houston put it — a fair description of the sage grouse mating ritual. In the strange game of land-use rock-paper-scissors, mining also trumps cattle, which is why some local ranchers have approached the Protect the Owyhee organizers to unite against the miners. (There are slight differences in protections depending on whether the Owyhee is made a wilderness area by Congress or a monument by Biden; the latter option can’t be as prescriptive about flexible grazing operations for ranchers, which is why, on the whole, the ranching community strongly prefers a legislative route.)

Most of the would-be monument is outside the McDermitt Caldera, but the fear isn’t so much that any one transmission project or hydro facility or lithium mine would “ruin” the Owyhee. “Everyone says, ‘Well, why do you have to protect it? Is there a threat?’” Houston said. “There are potential threats; people have been talking about different things like interstate highways or transmission or new mines. If we wait until those threats are real, then we’ve got a conflict, and then everyone’s going to say, ‘Well, why didn’t you protect it before?’”

Ironically, some fear that a formal monument designation will draw attention from the crowds that are loving to death other popular parks across the West. Standing in Leslie Gulch, where the red blades of rhyolite rock strongly resemble plates on the back of an enormous Stegosaurus, I sympathized with the impulse to gatekeep the landscape; driving from one remarkable site to the next, we’d barely seen another car all day. That’s changing regardless of whether the Owyhee is signposted as a destination in name or not: Chris Geroro, a local fly fisher who’s been guiding on the Owyhee River for 16 years, said he’s gone from “being the only person on the river to being one of the people on the river.”

The landscape certainly leaves an impression. “You go over this hill and then all of a sudden, boom! You’re in this amazing canyon,” he told me, describing the reaction of his out-of-town clients when they visit. “I just watch their jaws drop and the surprise of ‘Where did this come from? This is an hour outside of Boise?’” Those people then go home and post pictures, and more people understandably want to visit. A monument could help address the currently mostly unmanaged recreation.

But if Biden declines to move forward on protecting the Owyhee and an indifferent or actively hostile administration takes office in January, then the Oregon Natural Desert Association will have to switch strategies. Houston told me his team is already considering alternative approaches like pursuing a wilderness designation through the legislative branch. If, in a worst-case scenario, Trump decides to go after the land in the Owyhee, ONDA is prepared to go to court.

As we were leaving Leslie Gulch, Houston told me that he studied to be an evolutionary biologist. “What evolutionary biology is all about is understanding how species evolve based on what they have at that moment. They go forward with what they’ve got,” he said. “That’s what we’re doing in conservation — we’re going forward with what we’ve got.”

When it finally came time for me to return to Boise, I retraced the route I’d taken that morning into Succor Creek. The light was fading, but there was still enough for me to make out the hoodoo rock towers and the rolling sagebrush hills that I’d missed in the dark on my way into the canyon. To my surprise, enormous high-tension transmission towers also came into view; I’d driven beneath them hours before without even realizing it. Now, the silver power lines — future companions of the B2H — looked gossamer in the setting sun.

I parked to take a photo, and when I got out of the car, I felt a staticky tingle, like how a storm might excite the hairs on your arm. It was probably just a Placebo effect of standing under transmission lines and having spent the day thinking about electricity. But at that moment, I would have believed it was the passing ghost of an old cattleman glaring in my direction or perhaps the presence of something yet to come, something buzzing with potential, slung over my head.

I returned to my car and continued on to the highway. Soon, houses and small towns started to reappear, and I followed their lights through the dark back to Boise.

Marathon Mondays are tracking warmer in Boston.Climate.gov

Marathon Mondays are tracking warmer in Boston.Climate.gov

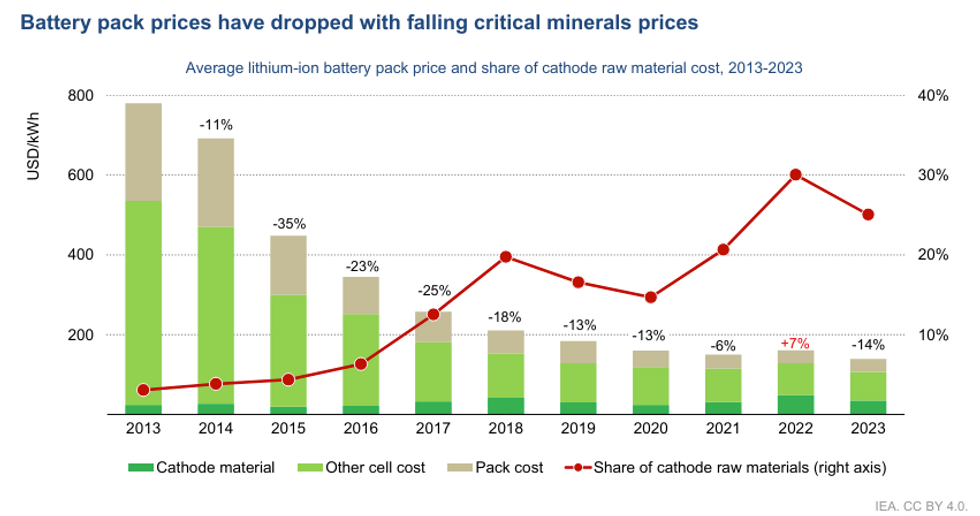

IEA

IEA

Courtesy of the Oregon Natural Desert Association.

Courtesy of the Oregon Natural Desert Association.