You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Even critical minerals can get complicated.

In northeastern Minnesota, a fight over the proposed NewRange Copper Nickel mine, better known as PolyMet, has dragged on for nearly two decades. Permits have been issued and revoked; state and federal agencies have been sued. The argument at the heart of the saga is familiar: Whether the pollution and disruption the mine will create are worth it for the jobs and minerals that it will produce.

The arguments are so familiar, in fact, that one wonders why we haven’t come up with a permitting and approval process that accounts for them. In total, the $1 billion NewRange project required more than 20 state and federal permits to move forward, all of which were secured by 2019. But since then, a number have been revoked or remanded back to the permit-issuing agencies. Just last year, for instance, the Army Corps of Engineers rescinded NewRange’s wetlands permit on the recommendation of the Environmental Protection Agency.

The messy history of this mine displays the difficult decisions the U.S. faces when it comes to securing the critical minerals that are key to a clean energy future — and the ways in which our current regulatory and permitting infrastructure is ill-equipped to resolve these tensions.

All sides in this debate recognize that minerals like nickel and copper are vital to the energy transition. Nickel is an integral component in most lithium-ion EV battery chemistries, and copper is used across a whole swath of technologies — electric vehicles, solar panels, and wind turbines, to name a few.

“We recognize that you're going to need copper, nickel, and other minerals in order to have a functioning society and to make the clean energy transition that we're all interested in,” Aaron Klemz, Chief Strategy Officer at the Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy, told me. But along with a number of other environmental groups and the Fond du Lac band of the Minnesota Chippewa tribe, which lives downstream of the proposed mine, MCEA opposes the project. “You can’t not mine. We understand that. But you have to take it on a case-by-case basis.”

On the one hand, the Duluth Complex, where the NewRange mine would be sited, contains one of the world’s largest untapped deposits of copper, nickel and other key metals. However, the critical minerals in this water-rich environment are bound to sulfide ores that can release toxic sulfuric acid when exposed to water and air. The proposed mine sits in a watershed that would eventually flow into Lake Superior, a critical source of drinking water for the Upper Midwest.

Many advocacy groups believe water pollution from the mine is inevitable, especially given NewRange’s plans for its waste basin. The current proposal involves covering the waste products, known as tailings, with water and containing the resulting slurry will with a dam. That’s considered much riskier than draining water from the tailings and “dry stacking” them in a pile. NewRange’s upstream dam construction method is also a concern, as the wet tailings can erode the dam’s walls more easily than with other designs. An upstream dam collapsed in Brazil in 2019, leading the country to ban this type of construction altogether.

And lastly, there’s the narrow question of the NewRange dam’s bentonite clay liner. Late last year, an administrative law judge recommended that state regulators refrain from reissuing NewRange’s permit to mine on the grounds that this liner was not a “practical and workable” method of containing the tailings.

Christie Kearney, director of sustainability, environmental and regulatory affairs for NewRange Copper Nickel, called these criticisms “tired and worn talking points” in a follow-up email to me, and said that the concerns simply don’t hold water “after the most comprehensive and lengthy environmental review and permitting process in Minnesota history.” The bentonite issue in particular, she told me, represents one of the main reasons permitting has been so challenging. “Instead of allowing agencies (who have the expertise) to make these decisions as established in Minnesota law, the regulatory decisions get challenged in court by mining opponents, leaving it to judges (who don’t have the technical expertise) to make these determinations,” she wrote.

The whole process could have gone more smoothly if all the stakeholders were involved from the beginning, she told me when we spoke. “In particular, we have a number of state permits that are overseen by the EPA, yet the EPA isn't involved until the very end, which has caused frustration both in our environmental review process as well as our permitting process.”

Klemz has another approach to ending the confusion. What is needed, he said, is a pathway to shut down projects once and for all if they’re deemed too environmentally hazardous. “There is no way to say no under the system we have now,” he told me. While courts can deny or revoke a permit, companies like NewRange can always go back to the drawing board and resubmit. “What we have instead is a system where the company has the incentive to keep on trying over and over and over again, despite whatever setback they encounter.”

While there’s no systematic way to block a mine, myriad avenues can lead to a “no.” Last year, the federal government placed a moratorium on mining on federal lands upstream of Minnesota’s Boundary Waters Canoe Wilderness Area, effectively shutting down another proposed copper-nickel mine. And the EPA banned the disposal of mine waste near Alaska’s proposed Pebble mine, blocking that project as well.

It’s a delicate balancing act, because ultimately the administration does want to incentivize domestic critical minerals production. The Inflation Reduction Act provides generous tax credits for companies involved in minerals processing, cathode materials production, and battery manufacturing. Then there’s the $7,500 credit available to consumers that purchase a qualifying EV, which depends on the automaker sourcing minerals from either the U.S. or a country the U.S. has a free-trade agreement with.

Under the current interpretation of the IRA, it’s possible that none of this money would flow directly to NewRange, since mineral extraction isn’t eligible for a tax credit, and it’s yet unclear whether the company will process the metals to a high enough grade to be eligible for credits there, either. Automakers that source from NewRange could benefit, but the project doesn’t currently have offtake agreements with any electric vehicle or clean energy company. That’s something that critics of the mine point to when NewRange touts its clean energy credentials.

“It's much more likely that this will end up in a string of Christmas lights than it will end up in a wind turbine in the United States,” Klemz told me. Of course, more critical minerals in the market overall will lower prices, thereby benefiting clean energy projects. But NewRange is a less neat proposition than, say, the proposed Talon Metals nickel mine, which is sited about two hours southwest of NewRange. As MIT Technology Review reports, this mine could unlock billions in federal subsidies through its offtake agreement with Tesla.

That hasn’t inoculated Talon from fierce local opposition, either. “As disinterested as the public may be in a lot of things, they are really engaged in a new mining project in their backyard,” said Adrian Gardner, Principal Nickel Markets Analyst at the energy and research consultancy Wood Mackenzie, which has been tracking both the Talon and NewRange mine since they were first proposed.

The Biden administration is also engaged. Two years ago, the Department of the Interior convened an interagency working group to make domestic minerals production more sustainable and efficient, starting with the Mining Law of 1872 — still the law of the land when it comes to new mining projects. The group released a report last September recommending, among other things, that the Bureau of Land Management and U.S. Forest Service provide standardized guidance to prospective developers and require meetings between all relevant agencies and potential developers before any applications are submitted. That means Congress will need to provide more resources to permitting agencies.

Those resources could come from a proposed royalty of between 4% and 8% on the net proceeds of minerals extracted from public lands, a fee that would also go to help communities most impacted by mining. The National Mining Association, of which NewRange is a member, has come out strongly against the report’s recommendations, highlighting the high royalties as a particular point of contention.

But many of the report’s proposals might have helped NewRange in its early days. “There were a lot of early missteps by the company,” Kearney admits. “The first draft [Environmental Impact Statement] that the company went through received a very poor reading from the EPA, and the company went back to its drawing board, changed out its leadership and its environmental leads.”

More stern rebukes, of course, would be the ideal for many advocacy groups. “I don't know how they could redesign it quite honestly, given what we know about the science, to comply with the law,” Klemz said.

Kearney is adamant, though, that even after five years of litigation, NewRange has no plans to give up the fight. “Not many companies can weather that,” Kearney said. Not many companies, however, are backed by mining giant Glencore. PolyMet, the project’s original developer, “really only survived because Glencore came in a few years back and invested over time until the point where they got 100% control,” Kearney told me.

Glencore, a $65 billion Swiss company, is pursuing the NewRange project in partnership with Teck Resources, which is worth $20 billion. The companies can afford to fight for a very long time, meaning nobody knows quite how or when this all ends.

“We do need this material. I get that,” Klemz told me. “So I don't really know if there's going to be some kind of neat future resolution to this.”

Kearney put it simply. “We don't have a timeline right now.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

The surge in electricity demand from data centers is making innovation a necessity.

Electric utilities aren’t exactly known as innovators. Until recently, that caution seemed perfectly logical — arguably even preferable. If the entity responsible for keeping the lights on and critical services running decides to try out some shiny new tech that fails, heating, cooling, medical equipment, and emergency systems will all trip offline. People could die.

“It’s a very conservative culture for all the right reasons,” Pradeep Tagare, a vice president at the utility National Grid and the head of its corporate venture fund, National Grid Partners, told me. “You really can’t follow the Silicon Valley mantra of move fast, break things. You are not allowed to break things, period.”

But with artificial intelligence-driven load growth booming, customer bills climbing, and the interconnection queue stubbornly backlogged, utilities now face little choice but to do things differently. The West Coast’s Pacific Gas and Electric Company now has a dedicated grid-innovation team of about 60 people; North Carolina-based utility Duke Energy operates an emerging technologies office; and National Grid, which serves U.S. customers in the Northeast, has invested in about 50 startups to date. Some 64% of utilities have expanded their innovation budgets in the past year, according to research by NGP, while 42% reported working with startups in some capacity.

The innovators on these teams are well aware that their reputation precedes them when it comes to bringing novel tech to market — and not in a flattering way. “I think historically we’ve done a poor job partnering with too many companies and spreading ourselves thin,” Quinn Nakayama, the senior director of grid research, innovation, and development at PG&E, told me. That’s led to a pattern known as “death by pilot,” in which utilities trial many promising solutions but are too risk-averse, cost-conscious, and slow-moving to deploy them, leaving the companies with no natural customers.

It doesn’t help that regulators such as public utilities commissions understandably require new investments to meet a strict “prudency” standard, proving that they can achieve the desired result at the lowest reasonable cost consistent with good practices. Yet this can be a high bar for tech that’s yet untested at scale. And because investor-owned utilities earn a guaranteed rate of return on approved infrastructure investments, they’re incentivized to pursue capital-intensive projects over smaller efficiency improvements. Freedom from the pressure of a competitive market has also traditionally meant freedom from the pressure to innovate.

But that’s changing.

To help bridge at least some of these divides, NGP set up a business development unit specifically for startups. “Their sole job is to work with our portfolio companies, work with our business units, and make sure that these things get deployed,” Tagare told me. Over 80% of the firm’s portfolio companies, he said, now have tie-ups of some sort with National Grid — be that a pilot or a long-term deployment — while “many” have secured multi-million dollar contracts with the utility.

While Tagare said that NGP is already reaping the benefits from investments in AI to streamline internal operations and improve critical services, hardware is slower to get to market. The startups in this category run the gamut from immediately deployable technologies to those still five or more years from commercialization. LineVision, a startup operating across parts of National Grid’s service territories in upstate New York and the U.K., is a prime example of the former. Its systems monitor the capacity of transmission lines in real-time via sensors and environmental data analytics, thus allowing utilities to safely push 20% to 30% more power through the wires as conditions permit.

There’s also TS Conductor, a materials science startup that’s developed a novel conductor wire with a lightweight carbon core and aluminum coating that can double or triple a line’s capacity without building new towers and poles. It’s a few years from achieving the technical and safety validation necessary to become an approved supplier for National Grid. Then five or more years down the line, NGP hopes to be able to deploy the startup Veir’s superconductors, which promise to boost transmission capacity five- to tenfold with materials that carry electricity with virtually zero resistance. But because this requires cooling the lines to cryogenic temperatures — and the bulky insulation and cooling systems need to do so — it necessitates a major infrastructure overhaul.

PG&E, for its part, is pursuing similar efficiency goals as it trials tech from startups including Heimdell Power and Smart Wires, which aim to squeeze more power out of the utility’s existing assets. But because the utility operates in California — the U.S. leader in EV adoption, with strong incentives for all types of home electrification — it’s also focused on solutions at the grid edge, where the distribution network meets customer-side assets like smart meters and EV charging infrastructure.

For example, the utility has a partnership with smart electric panel maker Span, which allows customers to adopt electric appliances such as heat pumps and EV chargers without the need for expensive electrical upgrades. Span’s device connects directly to a home’s existing electric panel, enabling PG&E to monitor and adjust electricity use in real time to prevent the panel from overloading while letting customers determine what devices to prioritize powering. Another partnership with smart infrastructure company Itron has similar aims — allowing customers to get EV fast chargers without a panel upgrade, with the company’s smart meters automatically adjusting charging speed based on panel limits and local grid conditions.

Of course, it’s natural to question how motivated investor-owned utilities really are to deploy this type of efficiency tech — after all, the likes of PG&E and National Grid make money by undertaking large infrastructure projects, not by finding clever means of avoiding them. And while both Nakayama and Tagare can’t deny what appears to be a fundamental misalignment of incentives, they both argue that there’s so much infrastructure investment needed — more than they can handle — that the friction is a non-issue.

“We have capital coming out of our ears,” Nakayama told me. Given that, he said, PG&E’s job is to accelerate interconnection for all types of loads, which will bring in revenue to offset the cost of the upgrades and thus lower customer rates. Tagare agreed.

“At least for the next — pick a number, five, seven, 10 years — I don’t see any of this slowing down,” he said.

And yet despite all that capital flow, PG&E still carries billions of dollars in wildfire-related financial obligations after its faulty equipment was found liable for sparking a number of blazes in Northern California in 2017 and 2018. The resulting legal claims drove the utility into bankruptcy in 2019, before it restructured and reemerged the following year. But the threat of wildfires in its service territory still looms large, which Nakayama said limits the company’s ability to allocate funds toward the basic poles and wires upgrades that are so crucial for easing the congested interconnection queue and bringing new load online.

Nakayama wants California’s legislature and courts to revise rules that make utilities strictly liable for wildfires caused by their equipment, even when all safety and mitigation procedures were followed. “In order for me to feel comfortable moving some of my investments out of wildfire into other areas of our business in a more accelerated fashion, I have to know that if I make the prudent investments for wildfire risk mitigation, I’m not going to be held liable for everything in my system,” he told me.

And while wildfire prevention itself is an area rich with technical innovation and a central focus of the utility’s startup ecosystem, Nakayama emphasizes that PG&E has a host of additional priorities to consider. “We need [virtual power plants]. We need new technologies. We need new investments. We need new capital. We need new wildfire-related liability,” he told me.

Utilities — especially his — rarely get seen as the good guys in this story. “I know that PGE gets vilified a lot,” Nakayama acknowledged. But he and his colleagues are “almost desperate to try to figure out how to bring down rates,” he promised.

Current conditions: The Central United States is facing this year’s largest outbreak of severe weather so far, with intense thunderstorms set to hit an area stretching from Texas to the Great Lakes for the next four days • Northern India is sweltering in temperatures as high as 13 degrees Celsius above historical norms • Australia issued evacuation alerts for parts of Queensland as floodwaters inundate dozens of roads.

The price of futures contracts for crude oil fell below $85 per barrel Monday after President Donald Trump called the war against Iran “very complete, pretty much,” declaring that there was “nothing left in a military sense” in the country. “They have no navy, no communications, they’ve got no air force. Their missiles are down to a scatter. Their drones are being blown up all over the place, including their manufacturing of drones,” Trump told CBS News in a phone interview Monday. “If you look, they have nothing left.”

The dip, just a day after prices surged well past $100 per barrel, highlights what Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin described as the challenge of depending too much on fossil fuels for a payday. “Even $85 is substantially higher than the $57 per barrel price from the end of last year. At that point, forecasters from both the public and the private sectors were expecting oil to stick around $60 a barrel through 2026,” he wrote. “Of course, crude oil itself is not something any consumer buys — but those high prices would likely feed through to higher consumer prices throughout the U.S. economy.”

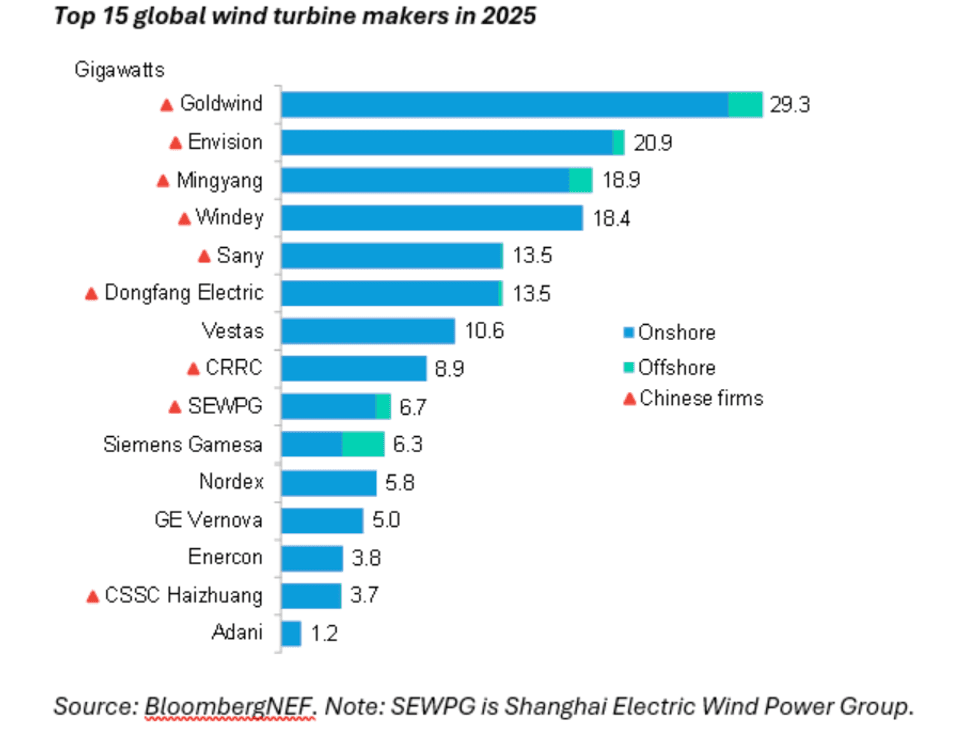

The global wind industry set a record last year, adding 169 gigawatts of turbines throughout 2025, according to the latest analysis from the consultancy BloombergNEF. The 38% surge compared to 2024 came as the momentum in the sector shifted to Asia. Chinese companies made up eight of the top 10 global wind turbine suppliers, the report found, as domestic installations in the People’s Republic reached an all-time high. India, meanwhile, edged out the U.S. and Germany as the world’s second largest market after China. Of all global wind additions, 161 gigawatts, or 95%, were onshore turbines, mostly spurred on by the domestic boom in China. Not only did that same building blitz help Beijing-based Goldwind hold onto its top spot as the world’s leading turbine supplier, it vaulted Chinese manufacturers into the next five slots in the global ranking. “Thanks to stable long-term policy support, wind installations over the past decade have become increasingly concentrated in mainland China,” Cristian Dinca, wind associate at BloombergNEF and lead author of the report, said in a statement. “Chinese manufacturers consistently top the global rankings. They benefitted particularly in 2025, as companies and provinces rushed to commission projects ahead of power market reforms and to meet targets set out in the Five Year Plan.”

Like in solar and batteries, the domestic boom in China is starting to spill over abroad. As Matthew wrote last year, Chinese manufacturers are making a big push into the European market.

Arizona’s utility regulator has repealed rules requiring electricity providers to generate at least 15% of their energy from renewables. Citing “dramatic” changes to the renewable energy landscape, the Arizona Corporation Commission said the cost to ratepayers of the rules adopted two decades ago was no longer justifiable, Utility Dive reported Monday. Since the rules first took effect in 2006, the utilities Arizona Public Services, Tucson Electric Power, and UniSource Energy Services “have collected more than $2.3 billion” in “surcharges from all customer classes to meet these mandates,” the regulator said in a press release following the March 4 ruling. “The mandates are no longer needed and the costs are no longer justified.”

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

Reflect Orbital wants to launch 50,000 giant mirrors into space to bounce sunlight to the night side of the planet to power solar farms after sunset, provide lighting to rescue workers, and light city streets. Now, The New York Times reported Monday, the Hawthorne, California-based startup is asking the Federal Communications Commission for permission to send its first prototype satellite into space with a 60-foot-wide mirror. The company, which has raised more than $28 million from investors, could launch its test project as early as this summer. The public comment period on the FCC application closed yesterday. “We’re trying to build something that could replace fossil fuels and really power everything,” Ben Nowack, Reflect Orbital’s chief executive, told the newspaper.

It’s emblematic of the kind of audacious climate interventions on which investors are increasingly gambling. Last fall, Heatmap’s Robinson Meyer broke news that Stardust Solutions, a startup promising to artificially cool the planet by spraying aerosols into the atmosphere that reflect the sun’s light back into space, had raised $60 million to commercialize its technology. In December, Heatmap’s Katie Brigham had a scoop on the startup Overview Energy raising $20 million to build panels in space and beam solar power back down to Earth.

Emerald AI is a startup whose software Katie wrote last year “could save the grid” by helping data centers to ramp electricity usage up and down like a smart thermostat to allow more computing power to come online on the existing grid. InfraPartners is a company that designs, manufactures, and deploys prefabricated, modular data centers parts. You don’t need to be an expert in the data center industry’s energy problems to hear the wedding bells ringing. On Tuesday, the two companies announced a deal to partner on what they’re calling “flex-ready data centers,” a version of InfraPartners’ off the shelf computing hardware that comes equipped with Emerald AI’s software. “Building more infrastructure the way we have historically will not be fast enough. We need to make the infrastructure we have more intelligent by leveraging AI,” Bal Aujla, InfraPartners’ director of advanced research and engineering, said in a statement. “This partnership will turn data centers from grid constraints into grid partners and unlock more usable capacity from existing infrastructure. The result will be enhanced AI deployment without compromising reliability or sustainability.” Rather than rush to invest in big new power plants, Emerald AI chief scientist Ayse Coskun said making data centers flexible means “we can prudently expand our grid.”

War in Iran may be halting shipments of oil and liquified natural gas out of the Persian Gulf. But that isn’t stopping Chinese clean energy manufacturers from preparing to send shipments toward the war-torn region. Despite the conflict, the Jiangsu-based Shuangliang announced last week that it had delivered 80 megawatts of electrolyzers to a Chinese port for shipment to a 300-megawatt green hydrogen and ammonia plant in the special economic zone in Duqm, Oman. I know what you’re going to say: Oman’s status as the region’s Switzerland — a diplomatic powerhouse with a modern history of strategic neutrality in even the most heated geopolitical conflicts — means it isn’t a target for Iranian missiles. And there’s no guarantee the shipment will head there immediately. But it’s a sign of how determined China’s electrolyzer industry is to sell its hardware overseas amid inklings of a domestic slowdown.

Topsy turvy oil prices aren’t great for the U.S.

Oil prices are all over the place as markets reopened this week, climbing as high as $120 a barrel before crashing to around $85 after Donald Trump told CBS News that the war with Iran “is very complete, pretty much,” and that he was “thinking about taking it over,” referring to the Strait of Hormuz, the artery through which about a third of the world’s traded oil flows.

Even $85 is substantially higher than the $57 per barrel price from the end of last year. At that point, forecasters from both the public and the private sectors were expecting oil to stick around $60 a barrel through 2026.

Of course, crude oil itself is not something any consumer buys — but those high prices would likely feed through to higher consumer prices throughout the U.S. economy. That includes the price of gasoline, of course, which has risen by about $0.50 a gallon in the past month, according to AAA, — and jet fuel, which will mean increased travel costs. “Book your airfares now if they haven’t moved already,” Skanda Amarnath, the executive director of the economic policy think tank Employ America, told me.

High oil prices also raise the price of goods and services not directly linked to oil prices — groceries, for instance. “The cost of food, especially at the grocery store, is a function of the cost of diesel,” which fuels the trucks that get food to shelves, Amarnath told me. Diesel prices have risen even more than gasoline in the past week, by over $0.85 a gallon.

“We’ll see how long these prices stay elevated, how they feed their way through the supply chain and the value chain. But it’s clearly the case that it is a pretty adverse situation for both businesses and consumers.”

The oil market is going through one of the largest physical shocks in its modern history. Bloomberg’s Javier Blas estimates that of the 15 million barrels per day that regularly flow through the Strait of Hormuz, only about a third is getting through to the global market, whether through the strait itself or by alternative routes, such as the pipeline from Saudi Arabia’s eastern oil fields to the Red Sea.

Global daily oil production is just above 100 million barrels per day, meaning that around 10% of the oil supply on the market is stuck behind an effective blockade.

“The world is suddenly ‘short’ a volume that, in normal times, would dwarf almost any supply/demand imbalance we debate,” Morgan Stanley oil analyst Martjin Rats wrote in a note to clients on Sunday.

The fact that the U.S. is itself a leading producer and exporter of oil will only provide so much relief. Private sector economists have estimated that every $10 increase in the price of oil reduces economic growth somewhere between 0.1 and 0.2 percentage points.

“Petroleum product prices here in the U.S. tend to reflect global market conditions, so the price at the pump for gasoline and diesel reflect what’s going on with global prices,” Ben Cahill, a senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told me. “What happens in the rest of the world still has a deep impact on U.S. energy prices.”

To the extent the U.S. economy benefits from its export capacity, the effects are likely localized to areas where oil production and export takes place, such as Texas and Louisiana. For the economy as a whole, higher oil prices will improve the “terms of trade,” essentially a measure of the value of imports a certain quantity of exports can “buy,” Ryan Cummings, chief of staff at Stanford Institute for Economic Policymaking, told me.

Could the U.S. oil industry ramp up production to capture those high prices and induce some relief?

Oil industry analysts, Heatmap founding executive editor Robinson Meyer, and the TV show Landman have all theorized that there is a “goldilocks” range of oil prices that are high enough to encourage exploration and production but not so high as to take out the economy as a whole. This range starts at around $60 or $70 on the low end and tops out at around $90 or $95. Above that, the economic damage from high prices would likely outweigh any benefit to drillers from expanded production.

And that’s if production were to expand at all.

“Capital discipline” has been the watchword of the U.S. oil and gas industry for years since the shale boom, meaning drillers are unlikely to chase price spikes by ramping up production heedlessly, CSIS’ Ben Cahill told me. “I think they’ll be quite cautious about doing that,” he said.