On Wednesday, the Biden administration finalized sweeping new rules that will sharply limit how much carbon pollution new cars and trucks can emit into the atmosphere. The rules — which rank as one of Biden’s most important climate moves — are aimed at accelerating the country’s transition to electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids, requiring most new cars sold in 2032 to burn little gasoline or none at all.

My colleague Emily Pontecorvo has an excellent explainer on how the new rules work. But I want to focus on one more aspect: Why they are able to do so much more than previous tailpipe regulations.

The new rules are not the Environmental Protection Agency’s first foray into regulating climate-warming pollution from vehicle tailpipes. Since 2010, the EPA has periodically tightened new limits on the amount of climate-warming pollution that cars and light-duty trucks can emit. The new rules are in some ways merely the next evolution of that approach.

But they also go much further than the agency ever has before. Where previous regulations essentially required automakers only to sell some conventional hybrids and electric vehicles, by the beginning of next decade, the lion’s share of cars sold in the United States must be electric vehicles or hybrids, the EPA now says.

Why is that ambition possible? One reason is that the United States has a more aggressive climate law on the books now than it has had during past rulemakings. Biden’s climate law, the Inflation Reduction Act, will subsidize the purchase, leasing, and manufacturing of electric vehicles. Because of how the EPA calculates the costs and benefits of its proposals, these subsidies will significantly cut the projected cost of even an ambitious rule — in this case by as much as $65 billion. (The agency calculates that consumers will save even more money — up to a staggering $230 billion — by paying less gasoline tax because they will be buying less fuel.)

Yet the IRA is not the only reason — or even the main reason — these rules can go so much further than what was previously imagined. If the United States can pursue such an ambitious standard now, that’s because it’s following on the heels of electric vehicle policy passed in other jurisdictions: China, California, and the European Union. These state and national policies have set the pace for the EV transition around the world, setting new market expectations or significantly cutting the costs of building an electric car.

They also created a sense of inevitability around electric vehicles. “The future is electric. Automakers are committed to the EV transition,” John Bozella, the president and CEO of the Alliance for Automotive Innovation, a car-industry trade group in Washington, said in a statement Wednesday on the EPA rules.

Corey Cantor, an analyst at the market research firm BNEF, summed it all up. “What is different this time — compared to say, where the world was in 2016 — is that there is now a thriving global EV market, versus a nascent one,” he said. There are also a handful of global companies poised to profit from a global EV transition, regardless of what Ford, Toyota, General Motors, and other legacy auto brands do.

Even before Biden asked the EPA to issue new regulations, in other words, these policies had changed the metaphorical game board — and changed how far the agency could push the rules.

These global policies don’t all take the same form. California and the European Union already require that all new cars sold in 2035 must be electric vehicles or plug-in hybrids, although the EU has carved out an exception for a theoretical zero-carbon gasoline replacement.

Due to a longstanding provision in the Clean Air Act, other U.S. states can opt into California’s stricter air pollution laws. So far, 14 in total — making up more than 40% of America’s light-duty car market — have adopted California’s 2035 zero-emissions vehicle mandate.

China, meanwhile, has not set a requirement that all cars must plug in by a certain year. Instead, it will require that “new energy vehicles” — a category that can include EVs and plug-in hybrids, but also conventional hybrids — must make up half of all car sales by 2035. But Chinese companies have raced ahead of this target. Wang Chuanfu, the CEO of the massive Chinese automaker BYD, estimated this weekend that 50% of China’s car sales could be new energy vehicles as soon as June.

All together, these mandates added up to a strong market signal. By last year, more than half of the global auto market was already covered by some form of clean vehicle rule — even before the EPA did anything final. Now, if the new EPA rules are enforced as written, then more than 60% of the world’s car market will be subject to some kind of emissions mandate.

This reflects, at least in part, a recognition that the global car market is changing beyond the ability of Washington politicians to influence it. “If we’re talking 10 years from now, policy probably won’t be needed, at least in leading markets. EVs will have just naturally taken over the market,” Stephanie Searle, who leads research programs at the International Council on Clean Transportation, told me.

Over the past year, a parade of cheap new EVs from Chinese automakers — including the BYD Seagull, a sub-$10,000 hatchback that gets up to 251 miles of range — have stunned the automotive industry. Jim Farley, the CEO of Ford, told investors last month that the company was reorienting its strategy to combat the rise of Chinese electric-car makers, such as BYD and Geely.

“If you cannot compete fair and square with the Chinese around the world, then 20% to 30% of your revenue is at risk,” Farley said at an industry conference last month. He disclosed that Ford had set up a secret internal “skunkworks” engineering team to make an affordable electric vehicle that could compete head-to-head with Chinese models on cost. The company has delayed the release of a new electric three-row SUV in order to produce three roughly $25,000 models, according to a Bloomberg report last week.

“Automakers see the future is electrified, and they see that Chinese companies will eat their lunch if they don’t get going,” Searle, the clean transportation researcher, said. “There’s no putting the genie back in the bottle.”

But China’s dominance was not inevitable — it was itself the result of ambitious industrial policies. Roughly 15 years ago, China identified the electric vehicle industry as a sector where it could eventually become a global leader in export markets, Benjamin Bradlow, a Princeton professor of sociology and international affairs, told me.

Since then, the country’s leaders have targeted the EV sector with generous subsidies far beyond what Americans lawmakers considered for the IRA, he said. They have also encouraged the EV industry’s geographic spread across China and required automakers to sell a certain percentage of EVs across their vehicle fleet.

“It’s a very different style of policymaking” from what America has done with the IRA, Bradlow said, although like that law it also aimed to lower the cost of technologies. “[China] is targeting a sector and it’s being very specific about being at the technological and price frontier — it’s very export-oriented.”

These policies have succeeded beyond imagining. China is now the world’s largest exporter of cars, and it has become a goliath in the EV industry. The country has achieved what hippies and renegades have long claimed is possible: a thriving and cutthroat electric vehicle industry, where consumers are willing to buy EVs without significant subsidies. (Indeed, China’s electric-car makers have been locked in a price war over the past year, driving even greater adoption as prices fall.)

These Chinese industrial policies — along with American and European-funded R&D — have cut tens of thousands of dollars from EV prices. Over the past three decades, the cost of manufacturing a battery has fallen by 97%, and by 2027 manufacturing a new EV battery is projected to cost less than $100 a kilowatt-hour, a long-theorized benchmark at which an electric vehicle will be competitive with a gasoline vehicle.

In the United States, mandates and subsidies in achieving mass EV adoption have not been quite as enthusiastically received. Some 7% of new cars sold in the United States last year were EVs, an all-time high. Plug-in and conventional hybrids made up an additional 8% of new car sales, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Those sales shares will need to double repeatedly in the years ahead for American automakers to meet the EPA’s new standards. And they point to at least one form of success that has alluded American policymakers so far: creating a robust, popular EV industry that can win over consumers on its own terms.

“The ultimate success of the policy and transition overall is a mix between policy, consumer adoption, and the automakers themselves,” Cantor, the BNEF analyst, told me.

For the first time ever, in other words, “automakers who fall behind may pay a far higher cost for failure to transition,” Cantor said. And that — above anything else — is what makes these EPA rules different from any that have come before.

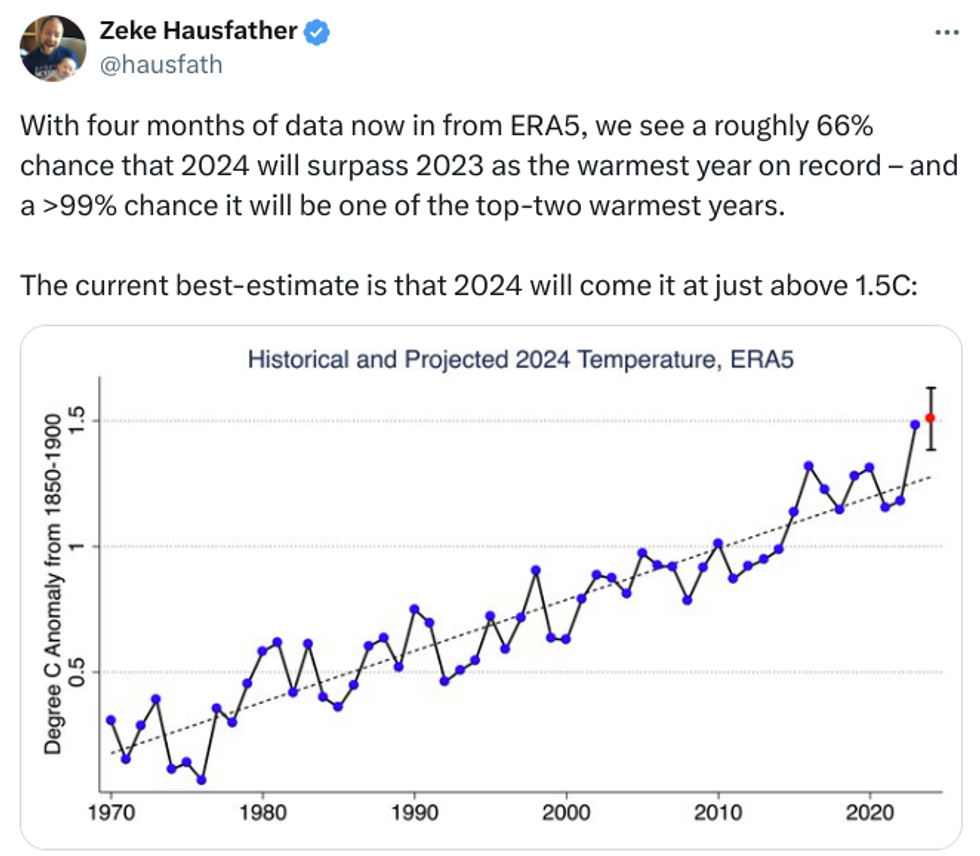

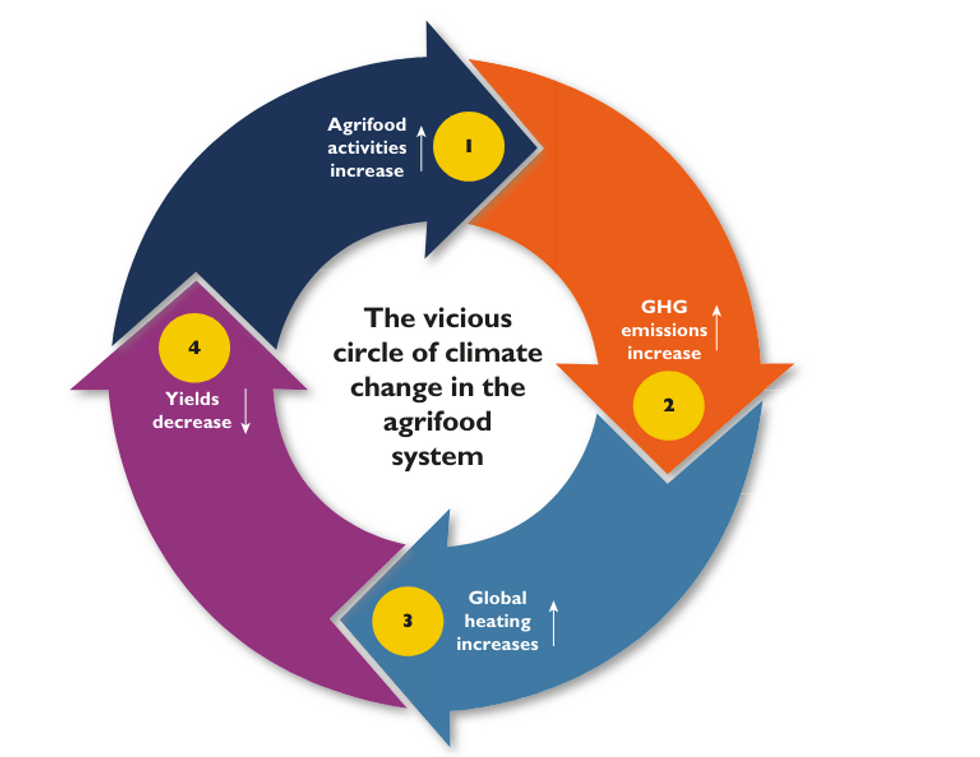

World Bank/Recipe for a Livable Planet report

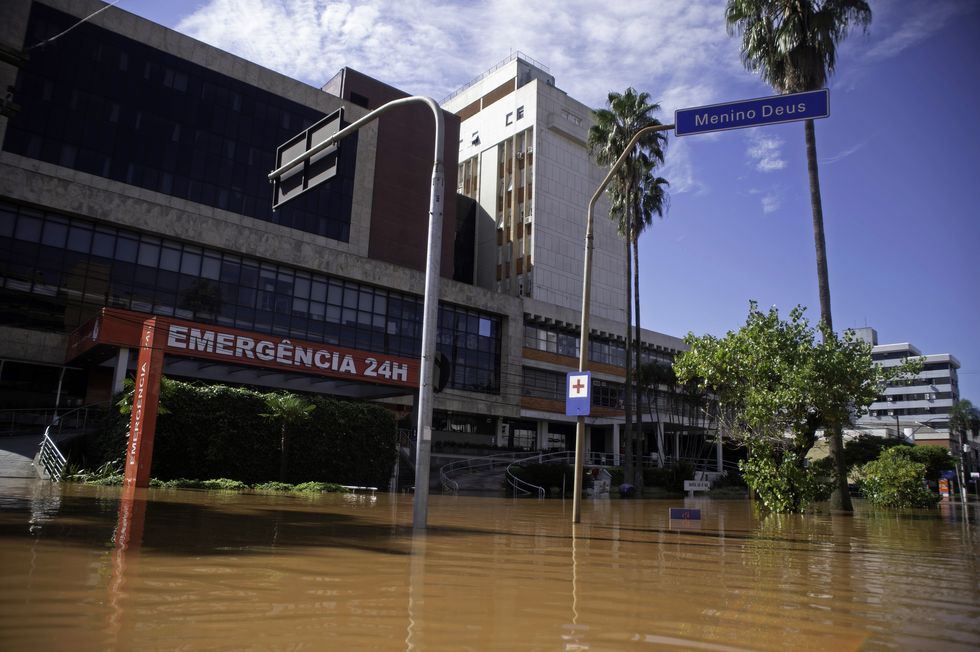

World Bank/Recipe for a Livable Planet report A flooded hospital entrance in Porto Alegre Max Peixoto/Getty Images

A flooded hospital entrance in Porto Alegre Max Peixoto/Getty Images Cypress Creek Renewables

Cypress Creek Renewables