You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

If the U.S. wants to compete on EVs, it will have to catch up to the rest of the world.

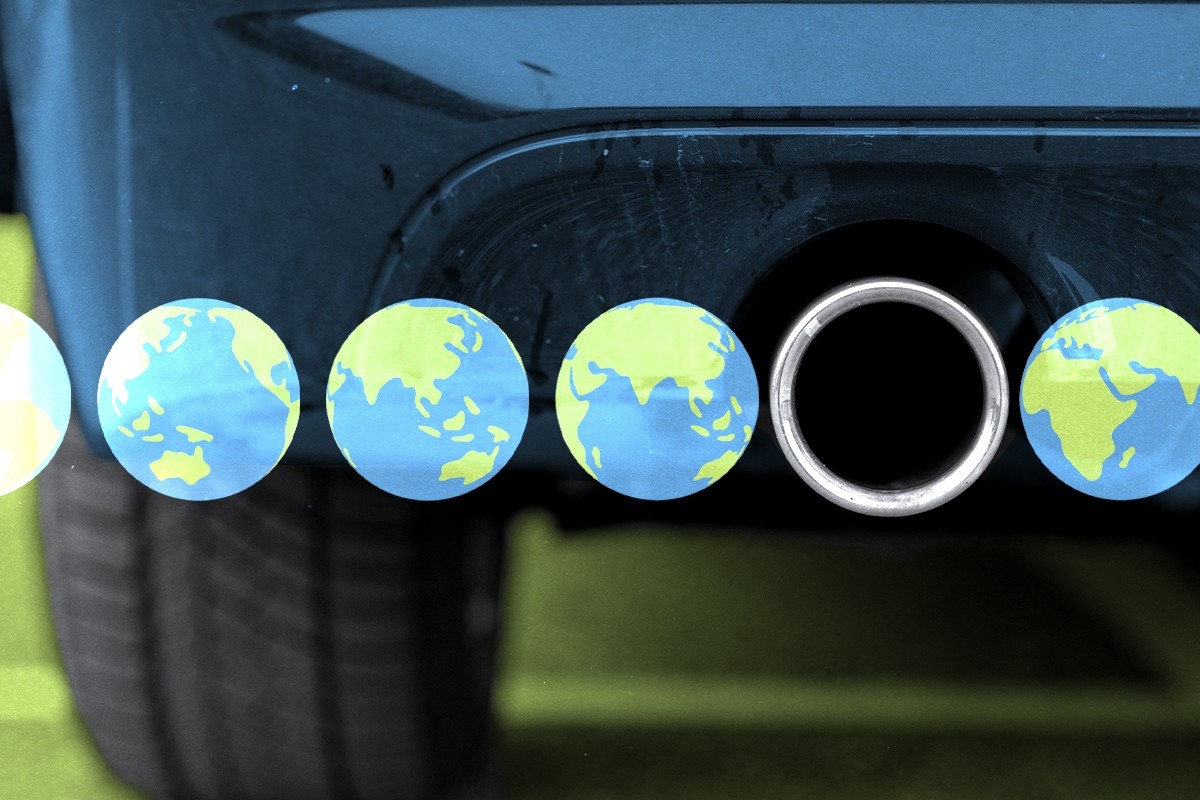

On Wednesday, the Biden administration finalized sweeping new rules that will sharply limit how much carbon pollution new cars and trucks can emit into the atmosphere. The rules — which rank as one of Biden’s most important climate moves — are aimed at accelerating the country’s transition to electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids, requiring most new cars sold in 2032 to burn little gasoline or none at all.

My colleague Emily Pontecorvo has an excellent explainer on how the new rules work. But I want to focus on one more aspect: Why they are able to do so much more than previous tailpipe regulations.

The new rules are not the Environmental Protection Agency’s first foray into regulating climate-warming pollution from vehicle tailpipes. Since 2010, the EPA has periodically tightened new limits on the amount of climate-warming pollution that cars and light-duty trucks can emit. The new rules are in some ways merely the next evolution of that approach.

But they also go much further than the agency ever has before. Where previous regulations essentially required automakers only to sell some conventional hybrids and electric vehicles, by the beginning of next decade, the lion’s share of cars sold in the United States must be electric vehicles or hybrids, the EPA now says.

Why is that ambition possible? One reason is that the United States has a more aggressive climate law on the books now than it has had during past rulemakings. Biden’s climate law, the Inflation Reduction Act, will subsidize the purchase, leasing, and manufacturing of electric vehicles. Because of how the EPA calculates the costs and benefits of its proposals, these subsidies will significantly cut the projected cost of even an ambitious rule — in this case by as much as $65 billion. (The agency calculates that consumers will save even more money — up to a staggering $230 billion — by paying less gasoline tax because they will be buying less fuel.)

Yet the IRA is not the only reason — or even the main reason — these rules can go so much further than what was previously imagined. If the United States can pursue such an ambitious standard now, that’s because it’s following on the heels of electric vehicle policy passed in other jurisdictions: China, California, and the European Union. These state and national policies have set the pace for the EV transition around the world, setting new market expectations or significantly cutting the costs of building an electric car.

They also created a sense of inevitability around electric vehicles. “The future is electric. Automakers are committed to the EV transition,” John Bozella, the president and CEO of the Alliance for Automotive Innovation, a car-industry trade group in Washington, said in a statement Wednesday on the EPA rules.

Corey Cantor, an analyst at the market research firm BNEF, summed it all up. “What is different this time — compared to say, where the world was in 2016 — is that there is now a thriving global EV market, versus a nascent one,” he said. There are also a handful of global companies poised to profit from a global EV transition, regardless of what Ford, Toyota, General Motors, and other legacy auto brands do.

Even before Biden asked the EPA to issue new regulations, in other words, these policies had changed the metaphorical game board — and changed how far the agency could push the rules.

These global policies don’t all take the same form. California and the European Union already require that all new cars sold in 2035 must be electric vehicles or plug-in hybrids, although the EU has carved out an exception for a theoretical zero-carbon gasoline replacement.

Due to a longstanding provision in the Clean Air Act, other U.S. states can opt into California’s stricter air pollution laws. So far, 14 in total — making up more than 40% of America’s light-duty car market — have adopted California’s 2035 zero-emissions vehicle mandate.

China, meanwhile, has not set a requirement that all cars must plug in by a certain year. Instead, it will require that “new energy vehicles” — a category that can include EVs and plug-in hybrids, but also conventional hybrids — must make up half of all car sales by 2035. But Chinese companies have raced ahead of this target. Wang Chuanfu, the CEO of the massive Chinese automaker BYD, estimated this weekend that 50% of China’s car sales could be new energy vehicles as soon as June.

All together, these mandates added up to a strong market signal. By last year, more than half of the global auto market was already covered by some form of clean vehicle rule — even before the EPA did anything final. Now, if the new EPA rules are enforced as written, then more than 60% of the world’s car market will be subject to some kind of emissions mandate.

This reflects, at least in part, a recognition that the global car market is changing beyond the ability of Washington politicians to influence it. “If we’re talking 10 years from now, policy probably won’t be needed, at least in leading markets. EVs will have just naturally taken over the market,” Stephanie Searle, who leads research programs at the International Council on Clean Transportation, told me.

Over the past year, a parade of cheap new EVs from Chinese automakers — including the BYD Seagull, a sub-$10,000 hatchback that gets up to 251 miles of range — have stunned the automotive industry. Jim Farley, the CEO of Ford, told investors last month that the company was reorienting its strategy to combat the rise of Chinese electric-car makers, such as BYD and Geely.

“If you cannot compete fair and square with the Chinese around the world, then 20% to 30% of your revenue is at risk,” Farley said at an industry conference last month. He disclosed that Ford had set up a secret internal “skunkworks” engineering team to make an affordable electric vehicle that could compete head-to-head with Chinese models on cost. The company has delayed the release of a new electric three-row SUV in order to produce three roughly $25,000 models, according to a Bloomberg report last week.

“Automakers see the future is electrified, and they see that Chinese companies will eat their lunch if they don’t get going,” Searle, the clean transportation researcher, said. “There’s no putting the genie back in the bottle.”

But China’s dominance was not inevitable — it was itself the result of ambitious industrial policies. Roughly 15 years ago, China identified the electric vehicle industry as a sector where it could eventually become a global leader in export markets, Benjamin Bradlow, a Princeton professor of sociology and international affairs, told me.

Since then, the country’s leaders have targeted the EV sector with generous subsidies far beyond what Americans lawmakers considered for the IRA, he said. They have also encouraged the EV industry’s geographic spread across China and required automakers to sell a certain percentage of EVs across their vehicle fleet.

“It’s a very different style of policymaking” from what America has done with the IRA, Bradlow said, although like that law it also aimed to lower the cost of technologies. “[China] is targeting a sector and it’s being very specific about being at the technological and price frontier — it’s very export-oriented.”

These policies have succeeded beyond imagining. China is now the world’s largest exporter of cars, and it has become a goliath in the EV industry. The country has achieved what hippies and renegades have long claimed is possible: a thriving and cutthroat electric vehicle industry, where consumers are willing to buy EVs without significant subsidies. (Indeed, China’s electric-car makers have been locked in a price war over the past year, driving even greater adoption as prices fall.)

These Chinese industrial policies — along with American and European-funded R&D — have cut tens of thousands of dollars from EV prices. Over the past three decades, the cost of manufacturing a battery has fallen by 97%, and by 2027 manufacturing a new EV battery is projected to cost less than $100 a kilowatt-hour, a long-theorized benchmark at which an electric vehicle will be competitive with a gasoline vehicle.

In the United States, mandates and subsidies in achieving mass EV adoption have not been quite as enthusiastically received. Some 7% of new cars sold in the United States last year were EVs, an all-time high. Plug-in and conventional hybrids made up an additional 8% of new car sales, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Those sales shares will need to double repeatedly in the years ahead for American automakers to meet the EPA’s new standards. And they point to at least one form of success that has alluded American policymakers so far: creating a robust, popular EV industry that can win over consumers on its own terms.

“The ultimate success of the policy and transition overall is a mix between policy, consumer adoption, and the automakers themselves,” Cantor, the BNEF analyst, told me.

For the first time ever, in other words, “automakers who fall behind may pay a far higher cost for failure to transition,” Cantor said. And that — above anything else — is what makes these EPA rules different from any that have come before.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Current conditions: The sun is coming out as New York City digs out of nearly two feet of snow, but temperatures are set to drop by 5 degrees Fahrenheit and more snow is forecast later this week • Floodwaters destroyed a major bridge in Migori, near Kenya’s shore of Lake Victoria, as rain continues every day this week across the country • The Solomon Islands are hunkering down in thunderstorms all week.

Electricity went out in more than 600,000 U.S. homes and businesses during the blizzard that pummeled the Northeast with two feet of snow. Massachusetts suffered the worst of the blackout, with nearly 300,000 customers still disconnected as of Monday night. New Jersey and Delaware trailed behind with more than 50,000 households each. In a show of the bicoastal nature of America’s grid fragility, intense winds in California also knocked out power lines and plunged tens of thousands more homes into darkness. Heavy snows put travel bans in effect across five states, but temperatures remained just above freezing in broad swaths of the country’s most densely populated region.

Winter Storm Fern, the Arctic weather that hit the Northeast at the end of last month, took out power for more than 1 million U.S. households, as I reported at the time. That’s due in part to the frigid air. As Heatmap’s Jeva Lange and Matthew Zeitlin wrote recently: “Put simply, cold temperatures stress the grid. That’s because cold can affect the performance of electricity generators as well as the distribution and production of natural gas, the most commonly used grid fuel. And the longer the grid has to operate under these difficult conditions, the more fragile it gets. And this is all happening while demand for electricity and natural gas is rising.”

The Supreme Court added just one new case to its oral argument docket upon returning Monday from its winter recess. The nation’s highest court has agreed to review a ruling by the Colorado Supreme Court in a case in which the oil and gas industry challenged Boulder County’s legal right to sue fossil fuel producers for damages from the effects of climate change under state law on the grounds that the companies knowingly destabilized the planet’s weather systems. In a lawsuit backed by Exxon Mobil, the Canadian fuel refiner Suncor Energy argued that the issues Boulder’s county commission cited in its suit fall under the federal government’s jurisdiction, thereby invalidating the basis for the litigation. While Colorado’s highest court said it aimed to “express no opinion on the ultimate viability of the merits of” Boulder’s claims when it rejected oil companies’ argument in 2023, the justices wrote that they believed the industry case boiled down to an argument that “a vague federal interest over interstate pollution, climate change, and energy policy must preempt Boulder’s claims.”

Heatmap’s Emily Pontecorvo laid out the stakes like this: “The case is arriving at the nation’s highest court in a particularly fraught moment for climate regulation. The Supreme Court ruled back in 2007 that the EPA had authority to regulate greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act, preventing states from creating a patchwork of their own emissions rules.” The case has come before the Supreme Court five times already, according to SCOTUSblog.

Once derided as a “false solution” that posed grave risks across human endeavors — even to the scientific process itself — environmental advocates have begun quietly to embrace the need at least study what technologies to artificially cool the planet might do now that a private geoengineering industry is rapidly emerging. (To brush up, re-read all the context my colleague Robinson Meyer wove into his scoop last year on a leading geoengineering startup raising its first major financing round.) Now the Natural Resources Defense Council is officially taking geoengineering seriously. Alongside three other partners, the green group launched a new project Tuesday morning to coordinate research governance on solar radiation management, the controversial suite of technologies that largely involve spraying reflective aerosols into the atmosphere to reflect the sun’s energy back into space.

Dubbed the Solar Geoengineering Research Governnance Platform, the project “will provide shared, voluntary tools that help research institutions demonstrate how decisions are made, risks are managed, and public concerns are addressed.” The NRDC said laboratory and university partners would be unveiled in upcoming announcements. “Solar geoengineering research is advancing faster than governance systems can keep pace,” Alliance for Just Deliberation on Solar Geoengineering executive director Shuchi Talati, a nonprofit that’s part of the new effort, said in a statement. “The goal is to carefully co-develop thoughtful, practical governance tools before research expansion narrows public choice.”

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

Despite a storm of tariffs and seachanges in federal policy, clean energy finance in 2025 “proved less fragile than the year’s headlines suggested.” That’s the conclusion of a new year-end report Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote up this morning by Crux Climate, the low-carbon fintech startup. “AI investment, data center development, delayed interconnection, and energy affordability reinforced the underlying investment case in 2025 for projects that could deliver power and reliability quickly and predictably,” the report found. “In this environment, clean energy and capital markets were remarkably resilient.” Investors gave out more capital than ever, but the market split. One on side, you had smaller developers, manufacturers, and biofuels companies that saw overall declining investment. On the other, you had soaring power investment.

The green steel startup Boston Metal, meanwhile, is cutting jobs after suffering what Canary Media called “a major setback.” The company said it had experienced an “unforeseen critical equipment failure” at its manufacturing plant in Brazil. While the incident was “fully contained, with no injuries or environmental impact,” the equipment damage prevented the startup from hitting an operational milestone needed to unlock a pending financial deal. As a result, “we lost access to committed capital essential to supporting our operations in both Brazil and the U.S.” Boston Metal is now laying off 71 employees in the U.S., amounting to nearly a quarter of its global workforce.

Amazon plans to pump $12 billion into new data center campuses in Louisiana, the company announced Monday. The push will create 540 full-time data center jobs and the tech giant will invest “up to $400 million in local water infrastructure” for the facilities. In a press release, the company pledged to pay for its own energy and utility infrastructure, and provide a $250,000 community fund to help support science education.

At least 25 data centers were abandoned last year following local opposition, according to a Heatmap Pro review that Rob wrote about last month. Data center fights, our colleague Jael Holzman wrote in November, are “swallowing American politics.”

Leave it to France to punch above its weight in nuclear energy. Last week, the WEST tokamak reactor at the French Commission of Atomic and Alternative Energies’ Cadarache laboratory broke a record in fusion energy. The reactor held a hot plasma for 1,337 seconds, slightly over 22 minutes. That beat the previous record set by a Chinese fusion facility weeks earlier by 25%. “WEST has achieved a new key technological milestone,” Anne-Isabelle Etienvre, the commission’s director of fundamental research, said in a statement. “Experiments will continue with increased power. This excellent result allows both WEST and the French community to lead the way for the future” large-scale experiments at the ITER international fusion research project.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct the description of the Solar Geoengineering Research Governnance Platform, including the group’s name and purpose.

There are two titanic forces in the clean energy market, and whichever one is stronger will determine the path of the post-One Big Beautiful Bill Act industry.

First there’s federal policy, which, thanks to OBBBA and the Trump administration’s war on renewable permitting, is making things more difficult for developers. Then there’s the technology: Soaring electricity demand from data centers, providing the business case for everything from co-located batteries and solar to small modular nuclear reactors.

“2025 is the storm at night, and there were all these cross-cutting winds that hit the boat. The ones that came from the front are the tariffs and the tax changes and wind cancellations or pauses,” Alfred Johnson, cofounder and chief executive of the clean energy finance platform Crux, told me. “Then the tailwinds at the back were interest rates, the continuation of many [other tax credits] in the OBBBA — including storage credits, nuclear credits, manufacturing credits — and substantial demand coming for the electricity and the components. And when the storm cleared in the morning, the boat is further ahead in the water than you would have anticipated.”

That’s the bifurcated story Crux — a marketplace for tax equity, tax credits, and debt financing — is telling in its 2025 market intelligence report, released Tuesday. There were splits in when investment happened and in which sectors were favored. There were better and worse times for investment. And there were countervailing forces pushing on the clean energy market.

Here’s how Crux views the clean energy financing market as it enters an uncertain time.

Crux found a split in activity between the first and second halves of last year across a number of markets. A lot of that could be chalked up to investors trying to front-run a partial or full repeal of the Inflation Reduction Act, which became all but inevitable following the 2024 election.

Overall there was $120 billion worth of lending to “clean power, fuels, and manufacturing projects” in 2025. That’s more than in 2024, but still a “materially lower growth rate” — 5.8% year over year, compared to 22% in 2024.

“Investment activity was front-loaded during the first half of 2025,” the report found, peaking in the first three months of the year and then declining through “the second and third quarters “as some investors waited to see how debate over the OBBB would resolve itself.” There was capital to be raised throughout 2025, but it “became increasingly selective over the course of the year,” Crux found.

Some $63 billion of tax credits changed hands — but again, there was a slowdown in the second half of the year due to uncertainty around how the OBBBA affected the market. Similarly, pricing for tax credits softened in the second half of the year, and deals got smaller.

Solar and storage “continued to represent a dominant share of current-year spot tax credit activity in 2025,” the Crux report says, making up just over half of the tax credit market. While solar on its own made up just over a third of the market, “storage-linked categories expanded most rapidly on a percentage basis, led by standalone storage, followed by solar and storage,” the team found.

Citing data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration showing that utility-scale storage deployment grew 72% over the course of 2025, from 11 gigawatts to 19 gigawatts, Johnson told me that storage is “categorically booming.”

“Storage was a major outlier and source of growth,” he said. “We continue as a country to provide a lot of support on top of a lot of demand for batteries, and that, in our view, is going to lead to a lot of continued deployment in the battery sector.”

But what about EVs? The large batteries in electric cars are a major source of demand that help catalyze the battery supply chain from the lithium and cobalt to the battery cells and packs. While the EV market may be getting hammered by inconsistent policy, battery manufacturing is still going strong, Johnson said, thanks to the demand for energy storage.

“There was a lot of pearl-clutching about what would happen to the battery supply chain with less policy support and EVs being less in favor,” he told me. “What you have seen is some number of those battery manufacturers have rotated their delivery and their product into grid-connected battery storage because that market has so much demand in it. So you’re still seeing a lot of that demand flow through into the need for capacity.”

Crux found that nearly a quarter of the Fortune 1000 companies are participating in the tax credit market. Their rising participation “drove the aggregate growth in the market and supported pricing despite rising market uncertainty following passage of the OBBB,” the report found.

When the market was just tax equity deals, in which investors partner directly with developers on a project in exchange for the value of the tax credits, it had only “a few dozen participants,” Johnson said. By 2023, a year after the Inflation Reduction Act allowed for those credits to be traded on third-party platform, it had around 50, he told me. Now that number is closer to 250.

“It’s becoming a more common part of the tax planning and cash management strategies that large companies are deploying,” Johnson said, pointing to data showing that tax credit buyers had effective tax rates three percentage points lower than non-buyers.

The Internal Revenue Service rolled out final rules for a new set of production and investment tax credits — the so-called tech neutral tax credits that applied to “any clean energy facility that achieves net-zero greenhouse gas emissions,” not just specific technologies chosen by Congress — in early 2025, just before the Biden administration left office.

Since then, these credits “have entered a choppy market,” the Crux report says.

“Crux’s survey of tax equity sponsors shows that most have limited investment in projects claiming the tech-neutral … credits,” which it attributed to concerns around stringent source requirements companies related to so-called foreign entities of concern must meet to claim these newer credits compared to the legacy investment and production tax credits.

Crux found modest but still measurable discounts for the tech-neutral tax credits compared to their predecessors of about 1 to 2 cents on the dollar for newer projects. (Projects that started construction before the end of 2024 were still eligible for the legacy credits.)

When talking to tax equity investors, Crux found that just 10%“reported actively pursuing tech-neutral tax credits,” while 90% said they would “only look at these credits under certain circumstances.”

“It’s mostly a comfort thing,” Johnson said. That may yet abate — he pointed out that “you saw preference in the early market for wind and solar credits versus advanced manufacturing and fuels and nuclear,” as new credits were developed, but eventually the market became more comfortable with funding new technologies and working with new credits, Johnson said.

“The new guidance that came out from the department on FEOC answers some of those questions,” Johnson said. “We think that that will drive some amount of additional market volume.”

The Supreme Court agreed to hear Suncor Energy Inc. v. County Commissioners of Boulder County, which concerns jurisdiction for “public nuisance” claims.

A new Supreme Court case will test whether the Trump administration’s war on federal climate regulation also undercuts fossil fuel companies’ primary defense against climate-related lawsuits.

On Monday, the court agreed to weigh in on whether Boulder, Colorado’s climate change lawsuit against major oil companies is preempted by federal law. Now that the federal government has revoked its own authority to regulate greenhouse gases, the justices will have to consider whether there even is any relevant federal law to speak of.

The case is arriving at the nation’s highest court in a particularly fraught moment for climate regulation. The Supreme Court ruled back in 2007 that the EPA had authority to regulate greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act, preventing states from creating a patchwork of their own emissions rules. The decision also shielded energy companies from federal common law “public nuisance” claims — lawsuits seeking damages for climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions.

Earlier this month, however, Trump’s EPA essentially challenged that Court decision. It made an official determination that the Clean Air Act did not, in fact, allow it to regulate emissions that have such diffuse, global effects.

“By revoking their authority on this issue, EPA, in our view, is basically eliminating what otherwise would have been a protection for companies against these kinds of lawsuits,” Andres Restrepo, a senior attorney at the Sierra Club, told me. “That really opens them up to a lot of potential legal liability and creates a lot of uncertainty.”

The new Supreme Court case dates back to 2018, when the city and county of Boulder, Colorado sued multinational oil giant ExxonMobil and Suncor, which operates the largest refinery in the state, for damages from climate change, bringing the charges under Colorado law. The oil companies tried repeatedly to get the case dismissed, arguing that it belonged in federal court. But time and again, the courts disagreed.

The Supreme Court already rejected an earlier petition to review the question of whether the case belonged in state or federal court in 2023. Now it has agreed to consider a slightly different petition, filed last summer, over whether federal law preempts Boulder’s state-law claims.

The Trump administration was acutely aware that its deregulatory moves had the potential to kick up a hornet’s nest of challenges for fossil fuel companies, so it tried to get ahead of the issue. In revoking the endangerment finding, the EPA claimed that while it “lacks statutory authority to regulate GHG emissions in response to global climate change concerns,” this has no impact on state preemption under the Clean Air Act. The agency’s final rule cites a section of that law about motor vehicle emission and fuel standards which says that states cannot adopt rules “relating to the control of emissions from new motor vehicles or new motor vehicle engines subject to this part.” In the agency’s view, this section applies broadly to any type of emission from a vehicle, whether or not the agency itself is tasked with regulating it.

The EPA also asserted that the Clean Air Act continues to preempt public nuisance claims, arguing that the Supreme Court did not base its dismissal of such claims on the EPA actually exercising any regulatory authority. The logic gets very circular here. Preemption “is no less applicable where, as here, the EPA does not regulate because Congress has not authorized such regulation as within the scope of its legal standard for determining what air pollution is dangerous and subject to regulation,” the agency wrote in its response to public comments on its initial proposal on this issue, which it published last summer.

“It feels like a bad ex-boyfriend who says, I don’t want to date you anymore, but you can’t date those other people either,” Vicki Arroyo, a law professor at Georgetown University and former Biden administration EPA official, told me.

Before the EPA finalized its decision on the endangerment finding, industry players were skittish about the legal implications. The Edison Electric Institute, the largest trade group for electric utilities, has not responded publicly to the final endangerment finding determination. It did, however, flag legal concerns in comments on the proposed rule last September, implicitly disagreeing with the EPA’s assertion that preemption was safe. It noted that the EPA’s actions could cast doubt on whether greenhouse gas emissions “remain a regulated pollutant under the Clean Air Act” in the power sector. That, in turn, could increase the likelihood that the power sector will be “further exposed to competing and conflicting regulations through a patchwork of state regulations” in addition to “the potential for increased litigation alleging common-law claims,” such as causing a public nuisance.

Automakers have also been virtually silent on the EPA’s actions. The Alliance for Automotive Innovation, the largest trade association for vehicle manufacturers, has not issued a statement on the matter. In its comments on the proposed rule, the group neither welcomed nor condemned the move. Unlike the power industry group, the automakers eagerly agreed with the EPA that rescinding the endangerment finding would not change federal preemption of state rules. It did warn, however, that eliminating greenhouse gas regulations altogether would subject the industry to yet another “rapid and dramatic” swing in policy that “puts billions of dollars of capital investment at risk.”

The only industry group I’ve seen come out firmly against the EPA’s final rule is the Zero Emissions Transportation Association, whose membership includes both automakers such as Rivian and utilities such as Duke Energy. Albert Gore, ZETA’s executive director, said in a statement that rescinding the endangerment finding “pulls the rug out from companies that have invested in manufacturing next-gen vehicles across the United States.” He also warned that it “opens businesses up to unnecessary legal risk,” including “a complicated patchwork of state regulations, threats of costly tort litigation, and inconsistent rules between markets.”

Ken Alex, a former senior assistant attorney general of California, was unequivocal that the EPA’s decision would open new avenues for public nuisance climate lawsuits. These suits are based on a complicated area of law known as federal common law, which permits courts to craft rules in very limited situations that have not been addressed by Congress. Alex represented California in the seminal 2011 Supreme Court case American Electric Power v. Connecticut, which established companies’ protection from federal public nuisance claims over greenhouse gas emissions. That decision sprang from the Court’s earlier 2007 decision that the Clean Air Act covers greenhouse gas emissions — which the EPA is now contesting.

The Boulder case will test how the Court views the EPA’s policy reversal long before legal challenges to the Trump administration get a hearing. SCOTUSblog reports that the Supreme Court is likely to hear oral arguments in the case, known as Suncor Energy Inc. v. County Commissioners of Boulder County, as soon as this fall. While the Boulder case contains similar public nuisance allegations to the American Electric Power case, Boulder brought them under state law, which means the legal questions and implications will be slightly different.

As for the possibility of a “patchwork of state regulations,” that’s a long ways away, if it is even possible at all, Alex said.

If the Supreme Court agrees with the EPA that the Clean Air Act does not apply to greenhouse gases, then there’s an argument that states are not precluded from acting, he told me. But there’s a counter-argument that any state action to regulate tailpipe greenhouse gas emissions will necessarily impact tailpipe emissions of other pollutants, bleeding into areas where Congress has explicitly preempted states from operating. “That’s also a good argument,” Alex said. “So it’s not clear to me how that would come out.”

Regardless, if the EPA’s final rule makes it through the highest court — which, to be sure, is not a foregone conclusion — Alex had no question that states would try to act. They will still have to meet the Clean Air Act’s general limits on air pollution, and California, for instance, “cannot meet those requirements without mobile source control,” he said. “They’ve got no choice but to seek regulations.”