You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Money is pouring in — and deadlines are approaching fast.

There’s no quick fix for decarbonizing medium- and long-distance flights. Batteries are typically too heavy, and hydrogen fuel takes up too much space to offer a practical solution, leaving sustainable aviation fuels made from plants and other biomass, recycled carbon, or captured carbon as the primary options. Traditionally, this fuel is much more expensive — and the feedstocks for it much more scarce — than conventional petroleum-based jet fuel. But companies are now racing to overcome these barriers, as recent months have seen backers throw hundreds of millions behind a series of emergent, but promising solutions.

Today, most SAF is made of feedstocks such as used cooking oil and animal fats, from companies such as Neste and Montana Renewables. But this supply is limited by, well, the amount of cooking oil or fats restaurants and food processing facilities generate, and is thus projected to meet only about 10% of total SAF demand by 2050, according to a 2022 report by the Mission Possible Partnership. Beyond that, companies would have to start growing new crops just to make into fuel.

That creates an opportunity for developers of second-generation SAF technologies, which involve making jet fuel out of captured carbon or alternate biomass sources, such as forest waste. These methods are not yet mature enough to make a significant dent in 2030 targets, such as the EU's mandate to use 6% SAF and the U.S. government’s goal of producing 3 billion gallons of SAF per year domestically. But this tech will need to be a big part of the equation in order to meet the aviation sector’s overall goal of net zero emissions by 2050, as well as the EU’s sustainable fuels mandate, which increases to 20% by 2035 and 70% by 2050 for all flights originating in the bloc.

“That’s going to be a massive jump because currently, SAF uptake is about 0.2% of fuel,” Nicole Cerulli, a research associate for transportation and logistics at the market research firm Cleantech Group, told me. The head of the airline industry’s trade association, Willie Walsh, said in December at a media day event, "We’re not making as much progress as we’d hoped for, and we’re certainly not making as much progress as we need.” While global SAF production doubled to 1 million metric tons in 2024, that fell far below the trade group’s projection of 1.5 million metric tons, made at the end of 2023.

Producing SAF requires making hydrocarbons that mirror those used in traditional jet fuel. We know how to do that, but the processes required — electrolysis, gasification, and the series of chemical reactions known as Fischer-Tropsch synthesis — are energy intensive. So finding a way to power all of this sustainably while simultaneously scaling to meet demand is a challenging and expensive task.

Aamir Shams, a senior associate at the energy think tank RMI whose work focuses on driving demand for SAF, told me that while sustainable fuel is undeniably more expensive than traditional fuel, airlines and corporations have so far been willing to pay the premium. “We feel that the lag is happening because we just don’t have the fuel today,” Shams said. “Whatever fuel shows up, it just flies off the shelves.”

Twelve, a Washington-based SAF producer, thinks its e-fuels can help make a dent. The company is looking to produce jet fuel initially by recycling the CO2 emitted from the ethanol, pulp, and paper industries. In September, the company raised $645 million to complete the buildout of its inaugural SAF facility in Washington state, support the development of future plants, and pursue further R&D. The funding includes $400 million in project equity from the impact fund TPG Rise Climate, $200 million in Series C financing led by TPG, Capricorn Investment Group, and Pulse Fund, and $45 million in loans. The company has also previously partnered with the Air Force to explore producing fuel on demand in hard to reach areas.

Nicholas Flanders, Twelve’s CEO, told me that the company is starting with ethanol, pulp, and paper because the CO2 emissions from these facilities are relatively concentrated and thus cheaper to capture. And unlike, say, coal power plants, these industries aren’t going anywhere fast, making them a steady source of carbon. To turn the captured CO2 into sustainable fuel, the company needs just one more input — water. Renewable-powered electrolyzers then break apart the CO2 and H2O into their constituent parts, and the resulting carbon monoxide and hydrogen are combined to create a syngas. That then gets put through a chemical reaction known as “Fischer-Tropsch synthesis,” where the syngas reacts with catalysts to form hydrocarbons, which are then processed into sustainable jet fuel and ultimately blended with conventional fuel.

Twelve says its proprietary CO2 electrolyzer can break apart CO2 at much lower temperatures than would typically be required for this molecule, which simplifies the whole process, making it easier to ramp the electrolyzers up and down to match the output of intermittent renewables. (How does it do this? The company didn’t respond when I asked.) Twelve’s first plant, which sources carbon from a nearby ethanol facility, is set to come online next year, producing 50,000 gallons of SAF annually once it’s fully scaled, with electrolyzers that will run on hydropower.

While Europe may have stricter, actually enforceable SAF requirements than the U.S., Flanders told me there’s a lot of promise in domestic production. “I think the U.S. has an exciting combination of relatively low-cost green electricity, lots of biogenic CO2 sources, a lot of demand for the product we’re making, and then the inflation Reduction Act and state level incentives can further enhance the economics.” Currently, the IRA provides SAF producers with a baseline $1.25 tax credit per gallon produced, which gradually increases the greener the fuel gets. Of course, whether or not the next Congress will rescind this is anybody’s guess.

Down the line, incentives and mandates will end up mattering a whole lot. Making SAF simply costs a whole lot more than producing jet fuel the standard way, by refining crude oil. But in the meantime, Twelve is setting up cost-sharing partnerships between airlines that want to reduce their direct emissions (scope 1) and large corporations that want to reduce their indirect emissions (scope 3), which include employee business travel.

For example, Twelve has offtake agreements with Seattle-based Alaska Airlines and Microsoft for the fuel produced at its initial Washington plant. Microsoft, which aims to reduce emissions from its employees’ flights, will essentially cover the cost premium associated with Twelve’s more expensive SAF fuel, making it cost-effective for Alaska to use in its fleet. Twelve has a similar agreement with Boston Consulting Group and an unnamed airline

Eventually, Flanders told me, the company expects to source carbon via direct air capture, but doing so today would be prohibitively expensive. “If there were a customer who wanted to pay the additional amount to use DAC today, we'd be very happy to do that,” Flanders said. “But our perspective is it will maybe be another decade before that cost starts to converge.”

No sustainable fuel is even close to cost parity yet — Cerulli told me that it generally comes with a “roughly 250% to over 800%” cost premium over conventional jet fuel. So while voluntary uptake by companies such as Microsoft and BCG are helping drive the emergent market today, that won’t be near enough to decarbonize the industry. “At the simplest level, the cost of not using SAF has to be higher than using it,” Cerulli told me.

Pathway Energy thinks that by incorporating carbon sequestration into its process, it can help the world get there. The sustainable fuels company, which emerged from stealth just last month, is pursuing what CEO Steve Roberts told me is “probably the most cost-efficient long-term pathway from a decarbonization perspective.” The company is building a $2 billion SAF plant in Port Arthur, Texas designed to produce about 30 million gallons of jet fuel annually — enough to power about 5,000 carbon-neutral 10-hour flights — while also permanently sequestering more than 1.9 million tons of CO2.

Pathway, a subsidiary of the investment and advisory firm Nexus Holdings, has partnered with the UK-based renewable energy company Drax, which will supply the company with 1 million metric tons of wood pellets, to be turned into fuel using a series of well-established technologies. The first step is to gasify the biomass by heating the pellets to high temperatures in the absence of oxygen to produce a syngas. Then, just as Twelve does, it puts the syngas through the Fischer-Tropsch process to form the hydrocarbons that become SAF.

The competitive advantage here is capturing the emissions from the fuel production process itself and storing them permanently underground. Since Pathway is burying CO2 that’s already been captured by the trees from which the wood pellets come, that would make Pathway’s SAF carbon-negative, in theory, while the best Twelve and similar companies can hope for is carbon neutrality, assuming all of their captured carbon is used to produce fuel.

The choice of Drax as a feedstock partner is not without controversy, however, as the BBC revealed that the company sources much of its wood from rare old-growth forests. Though this is technically legal, it’s also ecologically disruptive. Roberts told me Drax’s sourcing methodologies have been verified by third parties, and Pathway isn’t concerned. “I don't think any of that controversy has yielded any actually significant changes to their sourcing program at all, because we believe that they're compliant,” Roberts told me. “We are 100% certain that they’re meeting all the standards and expectations.”

Pathway has big growth plans, which depend on the legitimacy of its sustainability cred. Beyond the Port Arthur facility, which Roberts told me will begin production by the end of 2029 or early 2030, the company has a pipeline of additional facilities along the Gulf Coast in the works. It also has global ambitions. “When you have a fuel that is this negative, it really opens up a global market, because you can transport fuel out of Texas, whether that be into the EU, Africa, Asia, wherever it may be,” Roberts said, explaining that even substantial transportation-related emissions would be offset by the carbon-negativity of the fuel.

But alternative feedstocks such as forestry biomass are finite resources, too. That’s why many experts think that within the SAF sector, e-fuels such as Twelve’s that could one day source carbon via direct air capture and then electrolyze it have the greatest potential for growth. “It’s extremely dependent on getting sustainable CO2 and cheap electricity prices so that you can make cheap green hydrogen,” Shams told me. “But theoretically, it is unlimited in terms of what your total cap on production would be.”

In the meantime, airlines are focused on making their planes and engines more aerodynamic and efficient so that they don’t consume as much fuel in the first place. They’re also exploring other technical pathways to decarbonization — because after all, SAF will only be a portion of the solution, as many short and medium-length flights could likely be powered by batteries or hydrogen fuel. RMI forecasts that by 2050, 45% of global emissions reduction in the aviation sector will come from improvements in fuel efficiency, 37% will be due to SAF deployment, 7% will come from hydrogen, and 3.5% will come from electrification.

If you did the mental math, you’ll notice these numbers add up to 92.5% — not 100%. “What we have done is, let's look at what we are actually doing today and for the past three, four, five years, and let's see if we get to net zero or not. And the answer is, no. We don't get to net zero by 2050,” Shams told me. And while getting to 92.5% is nothing to scoff at, that means that the aviation sector would still be emitting about 700 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent by that time.

So what’s to be done? “The financing sector needs to step up its game and take a little bit more of a risk than they are used to,” Shams told me, noting that one of RMI’s partners, the Mission Possible Partnership, estimates that getting the aviation sector to net zero will require an investment of around $170 billion per year, a total of about $4.5 trillion by 2050. These numbers take a variety of factors into account beyond strictly SAF production, such as airport infrastructure for new fuels, building out direct air capture plants, etc.

But any way you cut it, it’s a boatload of money that certainly puts Pathway’s $2 billion SAF facility and Twelve’s $645 million funding round in perspective. And it’s far from certain that we can get there. “Increasingly, that goal of the 2050 net-zero target looks really difficult to achieve,” Shams put it simply. “Commitments are always going up, but more can be done.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Current conditions: The remnants of Tropical Storm Chantal will bring heavy rain and potential flash floods to the Carolinas, southeastern Virginia, and southern Delaware through Monday night • Two people are dead and 300 injured after Typhoon Danas hit Taiwan • Life-threatening rainfall is expected to last through Monday in Central Texas.

The flash floods in Central Texas are expected to become one of the deadliest such events in the past 100 years, with authorities updating the death toll to 82 people on Sunday night. Another 41 people are still missing after the storms, which began Thursday night and raised the Guadalupe River some 26 feet in less than an hour, providing little chance for holiday weekend campers and RVers to escape.

Although it’s far too soon to definitively attribute the disaster to climate change, a warmer atmosphere is capable of holding more moisture and producing heavy bursts of life-threatening rainfall. Disasters like the one in Texas are one of the “hardest things to predict that’s becoming worse faster than almost anything else in a warming climate, and it’s at a moment where we’re defunding the ability of meteorologists and emergency managers to coordinate,” Daniel Swain of the University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources told the Los Angeles Times. Meteorologists who spoke to Wired argued that the National Weather Service “accurately predicted the risk of flooding in Texas and could not have foreseen the extreme severity of the storm” ahead of the event, while The New York Times noted that staffing shortages at the agency following President Trump’s layoffs potentially resulted in “the loss of experienced people who would typically have helped communicate with local authorities in the hours after flash flood warnings were issued overnight.”

President Trump announced this weekend that his administration plans to send up to 15 letters on Monday to important trade partners detailing their tariff rates. Though Trump didn’t specify which countries would receive such letters or what the rates could be, he said the tariffs would go into effect on August 1 — an extension from the administration’s 90-day pause through July 9 — and range “from maybe 60% or 70% tariffs to 10% and 20% tariffs.” Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent added on CNN on Sunday that the administration would subsequently send an additional round of letters to 100 less significant trade partners, warning them that “if you don’t move things along” with trade negotiations, “then on August 1, you will boomerang back to your April 2 tariff level.” Trump’s proposed tariffs have already rattled industries as diverse as steel and aluminum, oil, plastics, agriculture, and bicycles, as we’ve covered extensively here at Heatmap. Trump’s weekend announcement also sent jitters through global markets on Monday morning.

President Trump’s gutting of the Inflation Reduction Act with the signing of the budget reconciliation bill last week will add an extra 7 billion tons of emissions to the atmosphere by 2030, a new analysis by Climate Brief has found. The rollback on renewable energy credits and policy means that “U.S. emissions are now set to drop to just 3% below current levels by 2030 — effectively flatlining — rather than falling 40% as required to hit the now-defunct [Paris Agreement] target,” Carbon Brief notes. As a result, the U.S. will be about 2 billion tons short of its emissions goal by 2030, adding an emissions equivalent of “roughly the annual output of Indonesia, the world’s sixth-largest emitter.”

To reach its conclusions, Carbon Brief utilized modeling by Princeton University’s REPEAT Project, which examined how the current obstacles facing U.S. wind and solar energy will impact U.S. emissions targets, as well as the likely slowdown in electric vehicle sales and energy efficiency upgrades due to the removal of subsidies. “Under this new set of U.S. policies, emissions are only expected to be 20% lower than 2005 levels by 2030,” Carbon Brief writes.

Engineering giant SKF announced late last week that it had set a new world record for tidal turbine reliability, with its systems in northern Scotland having operated continuously for over six years at 1.5 megawatts “without the need for unplanned or disruptive maintenance.” The news represents a significant milestone for the technology since “harsh conditions, high maintenance, and technical challenges” have traditionally made tidal systems difficult to implement in the real world, Interesting Engineering notes. The pilot program, MayGen, is operated by SAE Renewables and aims, as its next step, to begin deploying 3-megawatt powertrains for 30 turbines across Scotland, France, and Japan starting next year.

Satellites monitoring the Southern Ocean have detected for the first time a collapse and reversal of a major current in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. “This is an unprecedented observation and a potential game-changer,” said physicist Marilena Oltmanns, the lead author of a paper on the finding, adding that the changes could “alter the Southern Ocean’s capacity to sequester heat and carbon.”

A breakthrough in satellite ocean observation technology enabled scientists to recognize that, since 2016, the Southern Ocean has become saltier, even as Antarctic sea ice has melted at a rate comparable to the loss of Greenland’s ice. The two factors have altered the Southern Ocean’s properties like “we’ve never seen before,” Antonio Turiel, a co-author of the study, explained. “While the world is debating the potential collapse of the AMOC in the North Atlantic, we’re seeing that the Southern Ocean is drastically changing, as sea ice coverage declines and the upper ocean is becoming saltier,” he went on. “This could have unprecedented global climate impacts.” Read more about the oceanic feedback loop and its potential global consequences at Science Daily, here.

The French public research university Sciences Po will open the Paris Climate School in September 2026, making it the first school in Europe to offer a “degree in humanities and social sciences dedicated to ecological transition.” The first cohort will comprise 100 master’s students in an English-language program. “Faced with the ecological emergency, it is essential to train a new generation of leaders who can think and act differently,” said Laurence Tubiana, the dean of the Paris Climate School.

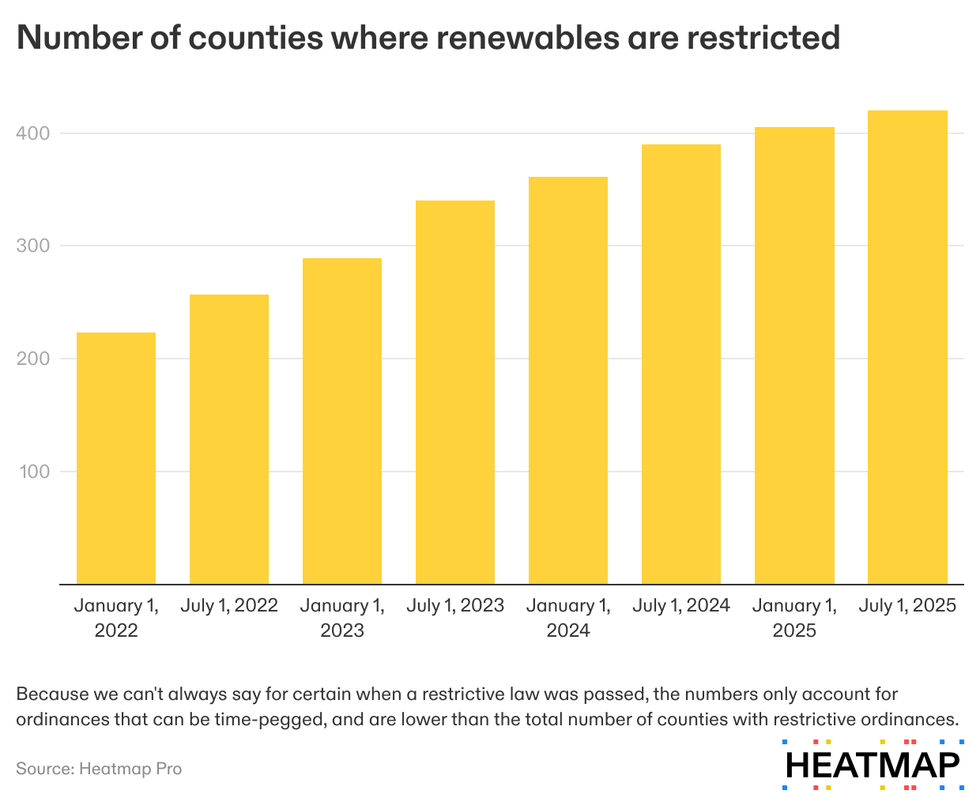

A fifth of U.S. counties now restrict renewables development, according to exclusive data gathered by Heatmap Pro.

A solar farm 40 minutes south of Columbus, Ohio.

A grid-scale battery near the coast of Nassau County, Long Island.

A sprawling wind farm — capable of generating enough electricity to power 100,000 homes — at the northern edge of Nebraska.

These projects — and hundreds of others — will never get built in the United States. They were blocked and ultimately killed by a regulatory sea-change that has reshaped how local governments consider and approve energy projects. One by one, counties and municipalities across the country are passing laws that heavily curtail the construction of new renewable power plants.

These laws are slowing the energy transition and raising costs for utility ratepayers. And the problem is getting worse.

The development of new wind and solar power plants is now heavily restricted or outright banned in about one in five counties across the country, according to a new and extensive survey of public records and local ordinances conducted by Heatmap News.

“That’s a lot,” Nicholas Bagley, a professor at the University of Michigan Law School, told us. Bagley said the “rash of new land use restrictions” owes partly to the increasing politicization of renewable energy.

Across the country, separate rules restrict renewables construction in 605 counties. In some cases, the rules greatly constrain where renewables can be built, such as by requiring that wind turbines must be placed miles from homes, or that solar farms may not take up more than 1% of a county’s agricultural land. In hundreds of other cases, the rules simply forbid new wind or solar construction at all.

Even in the liberal Northeast, where climate concern is high and municipalities broadly control the land use process, the number of restrictions is rising. At least 59 townships and municipalities have curtailed or outright banned new wind and solar farms across the Northeast, according to Heatmap’s survey.

Even though America has built new wind and solar projects for decades, the number of counties restricting renewable development has nearly doubled since 2022.

When the various state, county, and municipality-level ordinances are combined, roughly 17% of the total land mass of the continental United States has been marked as off limits to renewables construction.

These figures have not been previously reported. Over the past 12 months, our energy intelligence platform Heatmap Pro has conducted what it believes to be the most comprehensive survey of county and municipality-level renewables restrictions in the United States. In part, that research included surveys of existing databases of local news and county laws, including those prepared by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University.

But our research team has also called thousands of counties, many of whose laws were not in existing public databases, and we have updated our data in real time as counties passed ordinances and opposed projects progress (or not) through the zoning process. This data is normally available to companies and individuals who subscribe to Heatmap Pro. In this story, we are making a high-level summary of this data available to the public for the first time.

Restrictions have proliferated in all regions of the country.

Forty counties in Virginia alone now have an anti-renewable law on the books, effectively halting solar development in large portions of the state, even as the region experiences blistering electricity load growth.

These anti-solar laws have even begun to slow down energy development across the sunny Southwest. Counties in Nevada and Arizona have rejected new solar development in the same parts of the state that have already seen a high number of solar projects, our data show. Since President Trump took office in January, the effect of these local rules have become more acute — while solar developers could previously avoid the rules by proposing projects on federal land, a permitting slowdown at the Bureau of Land Management is now styming solar projects of all types in the region, as our colleague Jael Holzman has reported.

In the Northeast and on the West Coast, where Democrats control most state governments, towns and counties are still successfully fighting and cancelling dozens of new energy projects. Battery electricity storage systems, or BESS projects, now draw particular ire. The high-profile case of the battery fire in Moss Landing, California, in January has led to a surge of local opposition to BESS projects, our data shows. So far in 2025, residents have cited the Moss Landing case when fighting at least six different BESS projects nationwide.

That’s what happened with Jupiter Power, the battery project proposed in Nassau County, Long Island. The 275-megawatt project was first proposed in 2022 for the Town of Oyster Bay, New York. It would have replaced a petroleum terminal and improved the resilience of the local power grid.

But opposed residents began attending public meetings to agitate about perceived fire and environmental risks, and in spring 2024 successfully lobbied the town to pass a six-month moratorium on battery storage systems. The developer of the battery storage system, Jupiter Power, announced it would withdraw after the town passed two consecutive extensions to the moratorium and residents continued agitating for tighter restrictions.

That pattern — a town passes a temporary moratorium that it repeatedly extends — is how many projects now die in the United States.

The Nebraska wind project, North Fork Wind, was effectively shuttered when Knox County passed a permanent wind-energy ban. And the solar project south of Columbus, Ohio? It died when the Ohio Power Siting Board ruled that “that any benefits to the local community are outweighed by public opposition” to the project, which would have generated 70 megawatts, enough to power about 9,000 homes.

The developers of both of these projects are now waging lengthy and expensive legal appeals to save them; neither has won yet. Even in cases where the developer ultimately prevails against a local law, opposition can waste years and raise the final cost of a project by millions of dollars.

Our Heatmap Pro platform models opposition history alongside demographic, employment, voting, and exclusive polling data to quantify the risk a project will face in every county in the country, allowing developers to avoid places where they are likely to be unsuccessful and strategize for those where they have a chance.

Access to the full project- and county-level data and associated risk assessments is available via Heatmap Pro.

And more on the week’s biggest conflicts around renewable energy projects.

1. Jackson County, Kansas – A judge has rejected a Hail Mary lawsuit to kill a single solar farm over it benefiting from the Inflation Reduction Act, siding with arguments from a somewhat unexpected source — the Trump administration’s Justice Department — which argued that projects qualifying for tax credits do not require federal environmental reviews.

2. Portage County, Wisconsin – The largest solar project in the Badger State is now one step closer to construction after settling with environmentalists concerned about impacts to the Greater Prairie Chicken, an imperiled bird species beloved in wildlife conservation circles.

3. Imperial County, California – The board of directors for the agriculture-saturated Imperial Irrigation District in southern California has approved a resolution opposing solar projects on farmland.

4. New England – Offshore wind opponents are starting to win big in state negotiations with developers, as officials once committed to the energy sources delay final decisions on maintaining contracts.

5. Barren County, Kentucky – Remember the National Park fighting the solar farm? We may see a resolution to that conflict later this month.

6. Washington County, Arkansas – It seems that RES’ efforts to build a wind farm here are leading the county to face calls for a blanket moratorium.

7. Westchester County, New York – Yet another resort town in New York may be saying “no” to battery storage over fire risks.