You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

“It’s Confederate Disneyland, and it’s about to be SeaWorld,” says Susan Crawford, the author of a new book about the city.

In the last few years, climate change has made its impact known in violent, eye-grabbing ways. Heat waves and drought slowly roll across the planet; hurricanes and floods and wildfires bring sudden devastation to communities that were once safe. But there are also slower, more insidious impacts that we can easily forget about in the wake of those disasters, including the most classic impact of them all: sea-level rise.

The East Coast is particularly vulnerable to rising seas, and in her new book Charleston: Race, Water, and the Coming Storm (Pegasus Books, April 4, 2023), Susan Crawford, a writer and professor at Harvard Law School, explores how the historic city, the largest in South Carolina, is preparing — or failing to prepare — for what’s to come. Flooding has become increasingly commonplace in Charleston, Crawford writes, and the city’s racial history has meant that low-income communities of color are bearing the worst of the impact, with little hope for relief.

Charleston is a bellwether for what the rest of the East Coast can expect as the waters of the Atlantic creep ever higher. When we spoke, Crawford, author of the books Fiber and The Responsive City, among others, began by describing her book as a survival story rather than a climate story. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Things are pigeonholed as climate inappropriately. This is more about the question of: Can we overcome our polarization and limitations as human beings and plan ahead for a rapidly accelerating cataclysm that will, in particular, hit the East Coast at three or four times the rate of speed it goes the rest of the world? Can we plan ahead? Can we think about what anybody with a belly button needs to thrive? Because after all, isn’t that the role of government?

I came to Charleston initially on a solo vacation in December 2017. I went there for Christmas. And it’s an interesting place, but I didn’t really know what the history of it was. And I decided to go back in February 2018 to interview the man who’d recently stepped down as mayor, Joe Riley. He had been mayor for 40 years. His tagline was America’s favorite mayor. And he had transformed Charleston over his tenure into a tourist magnet, seven million tourists a year. Lots of development. It became a food and arts destination. And I was just curious about Mayor Riley. So I contacted a local journalist named Jack Hitt, and he suggested that I ask the mayor about the water.

So, when I interviewed Riley, I asked him about flooding. And he’s a very charming guy, little bowtie, little khaki suit. And he clammed up. All he said was that it was going to be very expensive. That was it.

And I said, “huh, maybe there’s a story here.” And this became a quest to try to figure out what the Charleston story was. At first, I thought it was going to be a story of local government heroism. And in a sense, it still is. I think the city is, in a sense, doing what it can. But then I was lucky enough to be introduced to several Black resident leaders at Charleston who were very generous to me and explained what it’s like to be Black in Charleston, and the ongoing lack of a Black professional class in Charleston. There’s sort of the idea that the civil war never ended in Charleston: There’s a lack of Black advisors near the mayor, although there are Black members of city council.

Charleston’s successes and failures are just harbingers of what we will be seeing up and down the East Coast. They’re more visible in Charleston, and Charleston lives in the dreams of millions of people who want to visit. The failures of the structures around Charleston and inside Charleston are fractal in nature. They are replicated across the globe. It’s Confederate Disneyland, and it’s about to be SeaWorld.

Charleston is extremely low in terms of its topography. The peninsula itself was built on fill, like much of Boston. Enslaved people filled in the perimeter of what is now today’s peninsula. So about a third of that peninsula — the lower part where these gorgeous historical houses are — is five feet or less above sea level. And then these outlying suburbs, many of which were annexed into Charleston’s property tax base by Mayor Riley over the course of his mayoralty, were historically marshy wetlands. There’s very little high land in the entire city of Charleston. A lot of the area outside off the peninsula is about 10 feet or less above sea level. So Charleston’s topography sets it up for the threat of rising waters.

It’s actually more exposed than the Netherlands, because it’s not as if there are defined waterways that lead inland — it’s actually a gazillion interconnected tiny watersheds across a flat area. So water can just roll over the place unimpeded when it rises.

Charlestonians have almost gotten used to ongoing flooding, there’s a sort of complacency that sets in. And there’s also, I think, a sense in Charleston, that they’ve missed a lot of big storms recently, and maybe they believe it’s not going to happen to them. But they’re just one storm away from being flattened, basically.

Right now the city has a single planning horizon in mind, which is 2050, and a single level of sea level rise, which is 18 inches. That might be fine up until 2050. But after that we’re going to see very rapidly accelerating sea level rise — scientists are predicting more like three feet by 2070. And then at least five by the end of the century.

Get the best of Heatmap delivered to your inbox:

Charleston was the place where 40% of the enslaved people forcibly brought to America first step foot. It’s the place where, after the slave trade was outlawed in 1808, a great deal of the domestic slave trade was carried out. Its entire economy, initially, was based on extractive labor from enslaved people.

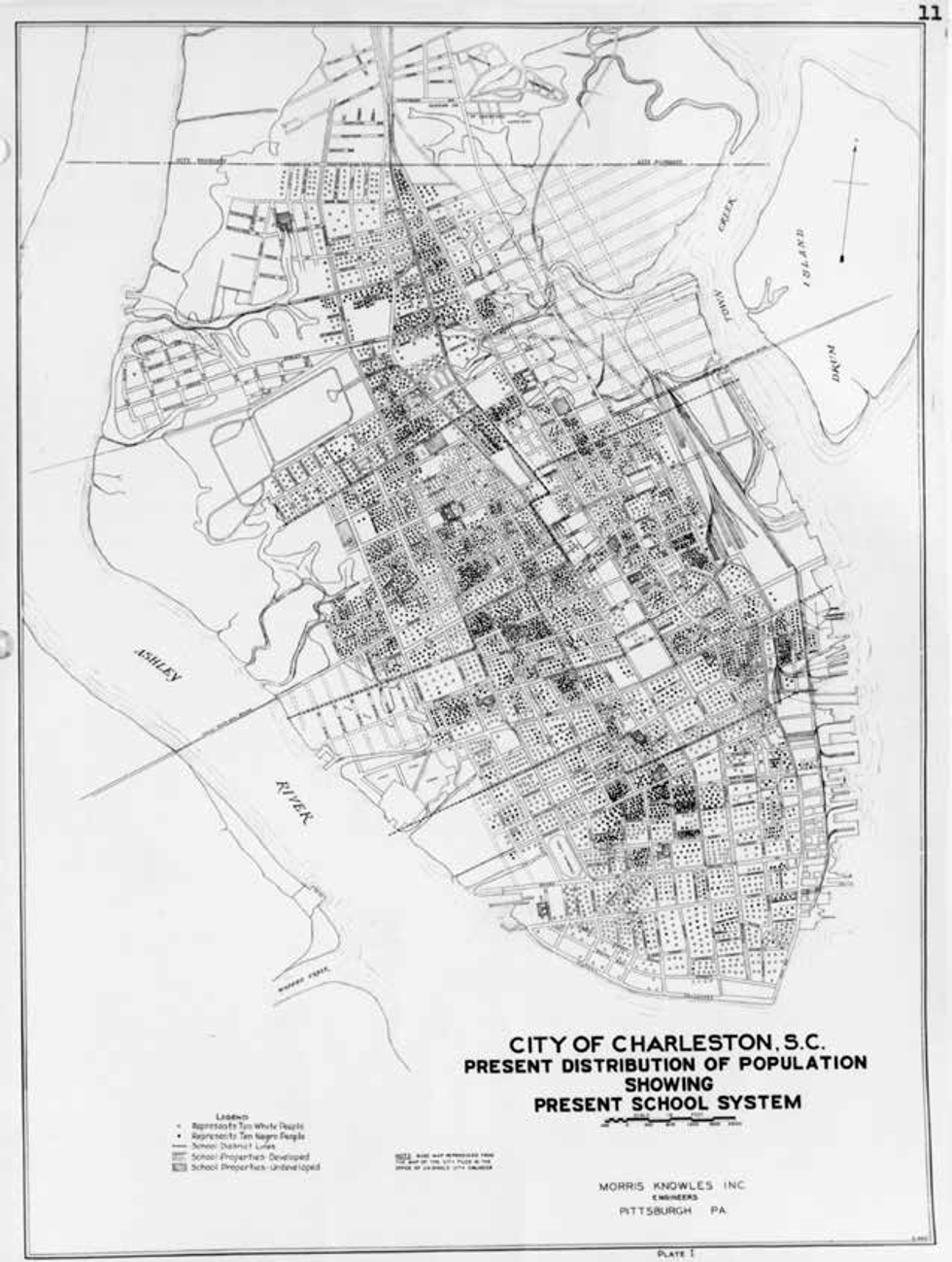

After the Civil War, a lot of free Black people moved onto the peninsula seeking work. Charleston in the 1970s was a majority Black peninsula, with 75% Black residents. Today, it’s at most 12 percent on the peninsula: That whole population has been displaced and moved to North Charleston, which has one of the highest eviction rates in the country, or off in far flung suburban areas where it’s cheaper. There are still some concentrated areas of Black residents on the peninsula on the east side, which floods all the time and has been a lower income area for all of Charleston’s history. And then there are public housing areas, mostly inhabited by Black residents.

Well, for a long time, Charleston, simply lived with flooding and let its sewage go right into the water. But in the late 19th century, a brilliant and energetic engineer figured out how to install tunnels underneath the streets of the peninsula that would drain sewage away from the houses and also take water out of the streets. It’s a gravity driven tunnel system, and a lot of that system is still in place.

But gravity isn’t going to help as the seas rise. The peninsula will be at the same level as the sea, so the gravity-based system won’t function. The city’s hard working stormwater manager is working on upgrading that system substantially, furnishing them with pumps, so they don’t have to rely just on gravity. But they’re going to need a lot of pumping to get the water off the streets in order to make life possible on the peninsula.

Mayor Riley, to his credit, developed a stormwater plan in 1984. But it was all very expensive, and many of the projects have not yet been completed, in particular on the west side of the peninsula. And all of that planning is premised on the idea that you’re supposed to pump the water off the peninsula, that no matter how much water there is, you’re going to take it away. That kind of money has not been invested in the outlying suburbs. When water comes there it just sits.

The other factor is that the groundwater in Charleston is very close to the surface. So as seas rise, the groundwater is also going to be rising and it will have nowhere to go. You know, they’re doing their best to think of ways to get that water away. But as rainwater gets heavier and seas rise, groundwater rises, and you’ll have a situation of chronic inundation.

This is gradually shifting, but at the state level, certainly, you’re better off not talking about the human causes of climate change. There’s no point. Because then you look as if you’re Al Gore, bringing the heavy hand of government everywhere, and that’s not a good look. And the state government makes it impossible for cities to include the idea of retreating in their comprehensive plans.

When I first interviewed current Mayor Tecklenburg about this whole subject, he said, “do you want to talk about climate change or sea level rise?” And at first I was befuddled, but then I understood what he was saying: Let’s not talk about why it’s happening. But we can talk about the fact that it is happening, because we see it every day.

And so that that’s the approach: Don’t talk about the causes, talk about what’s going on. And in fact, that is, for me, the entire approach of this book. I, of course, fully accept that humans are causing the forcing of temperatures to their stratospheric heights these days, and we need to lower emissions and do whatever we can to decarbonize our economy. But I’m concerned that even if we do that, the changes in the climate that are already baked in are going to have disastrous effects on human beings’ lives. So we need to be planning in both directions at once, both planning to reduce missions and planning to help people survive.

One of the leading characters here is Reverend Joseph Darby, who is a senior AME minister, and also the co chair of the local NAACP branch in Charleston. He’s in his 70s, very wise, and he has, of course, personally experienced flooding, and in particular, flooding that makes his church inaccessible since he’s a preacher on the peninsula.

He told me he learned early in his career that it was important never to be surprised by anything he heard in Charleston. He could be shocked, he could be astonished, but he couldn’t be surprised. He continues to feel that way in the absence of powerful Black voices advising the mayor.

His two boys moved away from Charleston, as much as he might have hoped that they would stay. The Black professional class doesn’t stay in Charleston because it’s just too hard. It’s just not worth it. He feels that there’s a sort of a benevolent paternalism from political leaders, a sense of “we know what’s best for you folks.”

The Black leaders I talked to pointed out that nobody is talking about how we’re going to help low income and Black residents of the region who have nowhere to go when the flooding hits in a big way. Nobody’s talking about the kind of holistic support services that are going to be needed, and this will just further entrench and amplify the inequality and unfairness. They also point out that this is a regional problem and national problem. And they just don’t see that kind of coordination happening.

Yeah, the big plan in Charleston is to work with the Army Corps of Engineers on building a 12-foot-tall wall around the peninsula with gates in it, that would, in theory, protect the peninsula from storm surges. The wall wouldn’t be designed to protect the 90% of people who don’t live on the peninsula. Nor would it be designed to do anything about the heavy rain or the constant high tides. It’s just for storm surges.

It’s a plan to protect the high property values on the peninsula, and in particular the areas that are good for tourism. You know, pillars of the Charleston economy. It’s fair to say that that if it’s ever built, that wall will be outmoded by the time it’s finished, because it’s built to a very low standard — 18 inches of sea level rise by 2050. The reason it’s built to such a low standard is that if it was any higher the wall would mess with the freeways that come onto the peninsula from the airport. And the Army Corps of Engineers representative was pretty frank about that. He said that just wouldn’t pencil out, that wouldn’t make sense economically to build anything higher.

So I mean, Charleston is stuck, because the only vessel for money right now is coming through these armoring projects being built by the Army Corps. And the plan is for that wall to be built in very slow sections, gradually protecting parts of the peninsula. As planned, it would take 30 years to build. So the underlying plan is for Charleston to be hit by a disaster that then causes enormous concern and empathy for Charleston, and a huge congressional appropriation bill. That’s what happened after Katrina. And then that wall would be finished quickly,

The wall as designed would not protect a couple of Black settlements farther up the peninsula, because the cost benefit analysis doesn’t work out. But it’s not Charleston’s fault that it’s planning on a disaster, because our entire approach to this survival question is premising on disaster recovery, not on proactive planning. There are 30 federal agencies that have all these scattershot programs that are aimed at disaster recovery, and there is very little advanced planning going on.

Well, in our country, we’ve had decades of exclusion through segregation and redlining and soft processes not quite understood by a lot of people that have pushed Black citizens into lower, more rapidly-flooding areas. And that history then plays out into what we decide to value. If our history has put Black Americans into more flood-prone, lower value housing over time, then it’s a garbage-in, garbage-out algorithm. If we then decide to only protect the places that are high property value, we will inevitably, yet again, exclude Black residents from the benefit of federal planning.

So it’s a pattern that was set a long time ago and did not arise by accident, playing out in the way we make decisions today.

And to its credit, the Biden administration just issued a terrific Economic Report of the President that said inequality and property values and ownership in the U.S. reflects decades of exclusion of racial minorities from home ownership and public investment, and we need different criteria to capture the differential vulnerability of these populations. So yeah, they’re on it. They understand.

No, Congress has already voted on the Charleston project. They say they’ve got this great benefit-cost ratio, one of the best in the nation, they’re really trumpeting it. It feels strange that we would pump billions of dollars into short sighted armoring of coastline that doesn’t protect against the daily harms we know are going to happen.

Well, people’s attachment to their homes is very deep. Not just for Black residents who can’t afford to leave, but for white residents and rich people as well. It’s likely it will take a series of disasters separated by very few months to convince everybody that this place really isn’t going to be livable. For decades, we already know that you can show maps to city planners, you can talk about the data to people until you’re blue in the face. This is especially true when it comes to coastal properties. It’s not rational. People are highly reluctant to leave.

It also could be a sudden cliff in property valuation, which is likely to happen in the next few years as there are actors in the financial system who fully understand this. Private flood insurers walked away from selling insurance there, leaving the federal government providing 95% or more of the flood insurance in Charleston. At some point, the fact that coastal real estate is now overvalued in the United States to the tune of $200 billion will be reflected in residential property markets up and down, and people will be unable to sell their houses. And then we might see a change in behavior.

The only country in the world that is actively talking about relocation is the Netherlands. They are planning or at least talking about needing to keep options open to move large populations away from Amsterdam, Rotterdam, towards Germany. But for everybody else, it is extremely difficult to talk about it. And you would hope that we wouldn’t have to have a global economic crisis to force planning, because that’s what this would amount to. It would be worse than 2008 if this overvaluation is suddenly corrected, because the loss of property value is permanent, and it’s not coming back. And it would be too bad if it took that kind of market crash to force planning in this direction.

If we had a president who was able to engage in long term planning, we could, with dignity and respect, change the financial drivers and levers and incentives to encourage people to understand this risk and move away from it without having to lose all their wealth. And without having to be cast into the role of migrants.

We absolutely can do this. We built the Hoover Dam, and we built the Interstate Highway System. We can afford what we care about. And if this was a priority, we could do this. But for me, the moment of redemption, the first moment of redemption will be when it’s somebody’s job in the White House to speak publicly about this constantly in league with the best scientists in the world.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

On electrolyzers’ decline, Anthropic’s pledge, and Syria’s oil and gas

Current conditions: Warmer air from down south is pushing the cold front in Northeast back up to Canada • Tropical Cyclone Gezani has killed at least 31 in Madagascar • The U.S. Virgin Islands are poised for two days of intense thunderstorms that threaten its grid after a major outage just days ago.

Back in November, Democrats swept to victory in Georgia’s Public Service Commission races, ousting two Republican regulators in what one expert called a sign of a “seismic shift” in the body. Now Alabama is considering legislation that would end all future elections for that state’s utility regulator. A GOP-backed bill introduced in the Alabama House Transportation, Utilities, and Infrastructure Committee would end popular voting for the commissioners and instead authorize the governor, the Alabama House speaker, and the Alabama Senate president pro tempore to appoint members of the panel. The bill, according to AL.com, states that the current regulatory approach “was established over 100 years ago and is not the best model for ensuring that Alabamians are best-served and well-positioned for future challenges,” noting that “there are dozens of regulatory bodies and agencies in Alabama and none of them are elected.”

The Tennessee Valley Authority, meanwhile, announced plans to keep two coal-fired plants operating beyond their planned retirement dates. In a move that seems laser-targeted at the White House, the federally-owned utility’s board of directors — or at least those that are left after President Donald Trump fired most of them last year — voted Wednesday — voted Wednesday to keep the Kingston and Cumberland coal stations open for longer. “TVA is building America’s energy future while keeping the lights on today,” TVA CEO Don Moul said in a statement. “Taking steps to continue operations at Cumberland and Kingston and completing new generation under construction are essential to meet surging demand and power our region’s growing economy.”

Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum said the Trump administration plans to appeal a series of court rulings that blocked federal efforts to halt construction on offshore wind farms. “Absolutely we are,” the agency chief said Wednesday on Bloomberg TV. “There will be further discussion on this.” The statement comes a week after Burgum suggested on Fox Business News that the Supreme Court would break offshore wind developers’ perfect winning streak and overturn federal judges’ decisions invalidating the Trump administration’s orders to stop work on turbines off the East Coast on hotly-contested national security, environmental, and public health grounds. It’s worth reviewing my colleague Jael Holzman’s explanation of how the administration lost its highest profile case against the Danish wind giant Orsted.

Thyssenkrupp Nucera’s sales of electrolyzers for green hydrogen projects halved in the first quarter of 2026 compared to the same period last year. It’s part of what Hydrogen Insight referred to as a “continued slowdown.” Several major projects to generate the zero-carbon fuel with renewable electricity went under last year in Europe, Australia, and the United States. The Trump administration emphasized the U.S. turn away from green hydrogen by canceling the two regional hubs on the West Coast that were supposed to establish nascent supply chains for producing and using green hydrogen — more on that from Heatmap’s Emily Pontecorvo. Another potential drag on the German manufacturer’s sales: China’s rise as the world’s preeminent manufacturer of electrolyzers.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

The artificial intelligence giant Anthropic said Wednesday it would work with utilities to figure out how much its data centers were driving up electricity prices and pay a rate high enough to avoid passing the costs onto ratepayers. The announcement came as part of a multi-pronged energy strategy to ease public concerns over its data centers at a moment when the server farms’ effect on power prices and local water supplies is driving a political backlash. As part of the plan, Anthropic would cover 100% of the costs of upgrading the grid to bring data centers online, and said it would “work to bring net-new power generation online to match our data centers’ electricity needs.” Where that isn’t possible, the company said it would “work with utilities and external experts to estimate and cover demand-driven price effects from our data centers.” The maker of ChatGPT rival Claude also said it would establish demand response programs to power down its data centers when demand on the grid is high, and deploy other “grid optimization” tools.

“Of course, company-level action isn’t enough. Keeping electricity affordable also requires systemic change,” the company said in a blog post. “We support federal policies — including permitting reform and efforts to speed up transmission development and grid interconnection — that make it faster and cheaper to bring new energy online for everyone.”

Syria’s oil reserves are opening to business, and Western oil giants are in line for exploration contracts. In an interview with the Financial Times, the head of the state-owned Syrian Petroleum Company listed France’s TotalEnergies, Italy’s Eni, and the American Chevron and ConocoPhillips as oil majors poised to receive exploration licenses. “Maybe more than a quarter, or less than a third, has been explored,” said Youssef Qablawi, chief executive of the Syrian Petroleum Company. “There is a lot of land in the country that has not been touched yet. There are trillions of cubic meters of gas.” Chevron and Qatar’s Power International Holding inked a deal just last week to explore an offshore block in the Mediterranean. Work is expected to begin “within two months.”

At the same time, Indonesia is showing the world just how important it’s become for a key metal. Nickel prices surged to $17,900 per ton this week after Indonesia ordered steep cuts to protection at the world’s biggest mine, highlighting the fast-growing Southeast Asian nation’s grip over the global supply of a metal needed for making batteries, chemicals, and stainless steel. The spike followed Jakarta’s order to cut production in the world’s biggest nickel mine, Weda Bay, to 12 million metric tons this year from 42 million metric tons in 2025. The government slashed the nationwide quota by 100 million metric tons to between 260 million and 270 million metric tons this year from 376 million metric tons in 2025. The effect on the global price average showed how dominant Indonesia has become in the nickel trade over the past decade. According to another Financial Times story, the country now accounts for two-thirds of global output.

The small-scale solar industry is singing a Peter Tosh tune: Legalize it. Twenty-four states — funny enough, the same number that now allow the legal purchase of marijuana — are currently considering legislation that would allow people to hook up small solar systems on balconies, porches, and backyards. Stringent permitting rules already drive up the cost of rooftop solar in the U.S. But systems small enough for an apartment to generate some power from a balcony have largely been barred in key markets. Utah became the first state to vote unanimously last year to pass a law allowing residents to plug small solar systems straight into wall sockets, providing enough electricity to power a laptop or small refrigerator, according to The New York Times.

The maker of the Prius is finally embracing batteries — just as the rest of the industry retreats.

Selling an electric version of a widely known car model is no guarantee of success. Just look at the Ford F-150 Lightning, a great electric truck that, thanks to its high sticker price, soon will be no more. But the Toyota Highlander EV, announced Tuesday as a new vehicle for the 2027 model year, certainly has a chance to succeed given America’s love for cavernous SUVs.

Highlander is Toyota’s flagship titan, a three-row SUV with loads of room for seven people. It doesn’t sell in quite the staggering numbers of the two-row RAV4, which became the third-best-selling vehicle of any kind in America last year. Still, the Highlander is so popular as a big family ride that Toyota recently introduced an even bigger version, the Grand Highlander. Now, at last, comes the battery-powered version. (It’s just called Highlander and not “Highlander EV,” by the way. The Highlander nameplate will be electric-only, while gas and hybrid SUVs will fly the Grand Highlander flag.)

The American-made electric Highlander comes with a max range of 287 miles in its less expensive form and 320 in its more expensive form. The SUV comes with the NACS port to charge at Tesla Superchargers and vehicle-to-load capability that lets the driver use their battery power for applications like backing up the home’s power supply. Six seats come standard, but the upgraded Highlander comes with the option to go to seven. The interior is appropriately high-tech.

Toyota will begin to build this EV later this year at a factory in Kentucky and start sales late in the year. We don’t know the price yet, but industry experts expect Highlander to start around $55,000 — in the same ballpark as big three-row SUVs like the Kia EV9 and Hyundai Ioniq 9 — and go up from there.

The most important point of the electric Highlander’s arrival, however, is that it signals a sea change for the world’s largest automaker. Toyota was decidedly not all in on the first wave (or two) of modern electric cars. The Japanese giant was content to make money hand over first while the rest of the industry struggled, losing billions trying to catch up to Tesla and deal with an unpredictable market for electrics.

A change was long overdue. This year, Toyota was slated to introduce better EVs to replace the lackluster bZ4x, which had been its sole battery-only model. That included an electrified version of the C-HR small crossover. Now comes the electrified Highlander, marking a much bigger step into the EV market at a time when other automakers are reining in their battery-powered ambitions. (Fellow Japanese brand Subaru, which sold a version of bZ4x rebadged as the Solterra, seems likely to do the same with the electric Highlander and sell a Subaru-labeled version of essentially the same vehicle.)

The Highlander EV matters to a lot of people simply because it’s a Toyota, and they buy Toyotas. This pattern was clear with the success of the Honda Prelude. Under the skin that car was built on General Motors’ electric vehicle platform, but plenty of people bought it because they were simply waiting for their brand, Honda, to put out an EV. Toyota sells more cars than anyone in the world. Its act of putting out a big family EV might signal to some of its customers that, yeah, it’s time to go electric.

Highlander’s hefty size matters, too. The five-seater, two-row crossover took over as America’s default family car in the past few decades. There are good EVs in this space, most notably the Tesla Model Y that has led the world in sales for a long time. By contrast, the lineup of true three-row SUVs that can seat six, seven, or even eight adults has been comparatively lacking. Tesla will cram two seats in the back of the Model Y to make room for seven people, but this is not a true third row. The excellent Rivian R1S is big, but expensive. Otherwise, the Ioniq 9 and EV9 are left to populate the category.

And if nothing else, the electrified Highlander is a symbolic victory. After releasing an era-defining auto with the Prius hybrid, Toyota arguably had been the biggest heel-dragger about EVs among the major automakers. It waited while others acted; its leadership issued skeptical statements about battery power. Highlander’s arrival is a statement that those days are done. Weirdly, the game plan feels like an announcement from the go-go electrification days of the Biden administration — a huge automaker going out of its way to build an important EV in America.

If it succeeds, this could be the start of something big. Why not fully electrify the RAV4, whose gas-powered version sells in the hundreds of thousands in America every year?

Third Way’s latest memo argues that climate politics must accept a harsh reality: natural gas isn’t going away anytime soon.

It wasn’t that long ago that Democratic politicians would brag about growing oil and natural gas production. In 2014, President Obama boasted to Northwestern University students that “our 100-year supply of natural gas is a big factor in drawing jobs back to our shores;” two years earlier, Montana Governor Brian Schweitzer devoted a portion of his speech at the Democratic National Convention to explaining that “manufacturing jobs are coming back — not just because we’re producing a record amount of natural gas that’s lowering electricity prices, but because we have the best-trained, hardest-working labor force in the history of the world.”

Third Way, the long tenured center-left group, would like to go back to those days.

Affordability, energy prices, and fossil fuel production are all linked and can be balanced with greenhouse gas-abatement, its policy analysts and public opinion experts have argued in a series of memos since the 2024 presidential election. Its latest report, shared exclusively with Heatmap, goes further, encouraging Democrats to get behind exports of liquified natural gas.

For many progressive Democrats and climate activists, LNG is the ultimate bogeyman. It sits at the Venn diagram overlap of high greenhouse gas emissions, the risk of wasteful investment and “stranded” assets, and inflationary effects from siphoning off American gas that could be used by domestic households and businesses.

These activists won a decisive victory in the Biden years when the president put a pause on approvals for new LNG export terminal approvals — a move that was quickly reversed by the Trump White House, which now regularly talks about increases in U.S. LNG export capacity.

“I think people are starting to finally come to terms with the reality that oil and gas — and especially natural gas— really aren’t going anywhere,” John Hebert, a senior policy advisor at Third Way, told me. To pick just one data point: The International Energy Agency’s latest World Energy Outlook included a “current policies scenario,” which is more conservative about policy and technological change, for the first time since 2019. That saw the LNG market almost doubling by 2050.

“The world is going to keep needing natural gas at least until 2050, and likely well beyond that,” Hebert said. “The focus, in our view, should be much more on how we reduce emissions from the oil and gas value chain and less on actually trying to phase out these fuels entirely.”

The memo calls for a variety of technocratic fixes to America’s LNG policy, largely to meet demand for “cleaner” LNG — i.e. LNG produced with less methane leakage — from American allies in Europe and East Asia. That “will require significant efforts beyond just voluntary industry engagement,” according to the Third Way memo.

These efforts include federal programs to track methane emissions, which the Trump administration has sought to defund (or simply not fund); setting emissions standards with Europe, Japan, and South Korea; and more funding for methane tracking and mitigation programs.

But the memo goes beyond just a few policy suggestions. Third Way sees it as part of an effort to reorient how the Democratic Party approaches fossil fuel policy while still supporting new clean energy projects and technology. (Third Way is also an active supporter of nuclear power and renewables.)

“We don’t want to see Democrats continuing to slow down oil and gas infrastructure and reinforce this narrative that Democrats are just a party of red tape when these projects inevitably go forward anyway, just several years delayed,” Hebert told me. “That’s what we saw during the Biden administration. We saw that pause of approvals of new LNG export terminals and we didn’t really get anything for it.”

Whether the Democratic Party has any interest in going along remains to be seen.

When center-left commentator Matthew Yglesias wrote a New York Times op-ed calling for Democrats to work productively with the domestic oil and gas industry, influential Democratic officeholders such as Illinois Representative Sean Casten harshly rebuked him.

Concern over high electricity prices has made some Democrats a little less focused on pursuing the largest possible reductions in emissions and more focused on price stability, however. New York Governor Kathy Hochul, for instance, embraced an oft-rejected natural gas pipeline in her state (possibly as part of a deal with the Trump administration to keep the Empire Wind 1 project up and running), for which she was rewarded with the Times headline, “New York Was a Leader on Climate Issues. Under Hochul, Things Changed.”

Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro (also a Democrat) was willing to cut a deal with Republicans in the Pennsylvania state legislature to get out of the Northeast’s carbon emissions cap and trade program, which opponents on the right argued could threaten energy production and raise prices in a state rich with fossil fuels. He also made a point of working with the White House to pressure the region’s electricity market, PJM Interconnection, to come up with a new auction mechanism to bring new data centers and generation online without raising prices for consumers.

Ruben Gallego, a Democratic Senator from Arizona (who’s also doing totally normal Senate things like having town halls in the Philadelphia suburbs), put out an energy policy proposal that called for “ensur[ing] affordable gasoline by encouraging consistent supply chains and providing funding for pipeline fortification.”

Several influential Congressional Democrats have also expressed openness to permitting reform bills that would protect oil and gas — as well as wind and solar — projects from presidential cancellation or extended litigation.

As Democrats gear up for the midterms and then the presidential election, Third Way is encouraging them to be realistic about what voters care about when it comes to energy, jobs, and climate change.

“If you look at how the Biden administration approached it, they leaned so heavily into the climate message,” Hebert said. “And a lot of voters, even if they care about climate, it’s just not top of mind for them.”