You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Inside Climeworks’ big experiment to wrest carbon from the air

In the spring of 2021, the world’s leading authority on energy published a “roadmap” for preventing the most catastrophic climate change scenarios. One of its conclusions was particularly daunting. Getting energy-related emissions down to net zero by 2050, the International Energy Agency said, would require “huge leaps in innovation.”

Existing technologies would be mostly sufficient to carry us down the carbon curve over the next decade. But after that, nearly half of the remaining work would have to come from solutions that, for all intents and purposes, did not exist yet. Some would only require retooling existing industries, like developing electric long-haul trucks and carbon-free steel. But others would have to be built from almost nothing and brought to market in record time.

What will it take to rapidly develop new solutions, especially those that involve costly physical infrastructure and which have essentially no commercial value today?

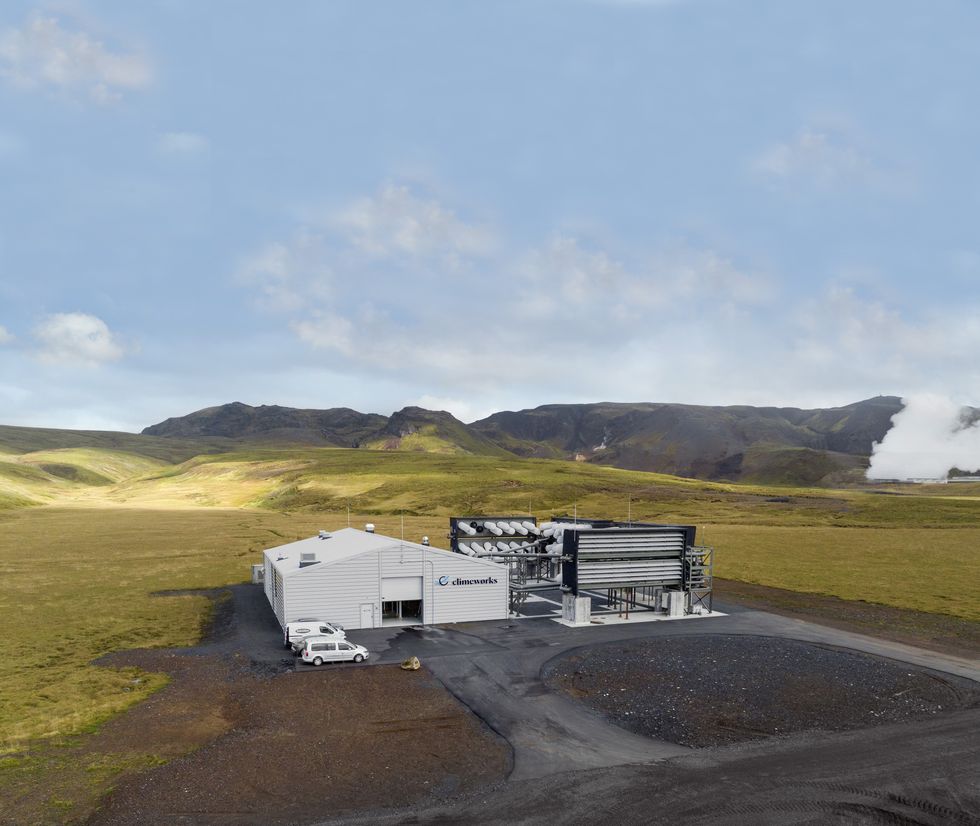

That’s the challenge facing Climeworks, the Swiss company developing machines to wrest carbon dioxide molecules directly from the air. In September 2021, a few months after the IEA’s landmark report came out, Climeworks switched on its first commercial-scale “direct air capture” facility, a feat of engineering it dubbed “Orca,” in Iceland.

The technology behind Orca is one of the top candidates to clean up the carbon already blanketing the Earth. It could also be used to balance out any stubborn, residual sources of greenhouse gases in the future, such as from agriculture or air travel, providing the “net” in net-zero. If we manage to scale up technologies like Orca to the point where we remove more carbon than we release, we could even begin cooling the planet.

As the largest carbon removal plant operating in the world, Orca is either trivial or one of the most important climate projects built in the last decade, depending on how you look at it. It was designed to capture approximately 4,000 metric tons of carbon from the air per year, which, as one climate scientist, David Ho, put it, is the equivalent of rolling back the clock on just 3 seconds of global emissions. But the learnings gleaned from Orca could surpass any quantitative assessment of its impact. How well do these “direct air capture” machines work in the real world? How much does it really cost to run them? And can they get better?

The company — and its funders — are betting they can. Climeworks has made major deals with banks, insurers, and other companies trying to go green to eventually remove carbon from the atmosphere on their behalf. Last year, the company raised $650 million in equity that will “unlock the next phase of its growth,” scaling the technology “up to multi-million-ton capacity … as carbon removal becomes a trillion-dollar market.” And just last month, the U.S. Department of Energy selected Climeworks, along with another carbon removal company, Heirloom, to receive up to $600 million to build a direct air capture “hub” in Louisiana, with the goal of removing one million tons of carbon annually.

Two years after powering up Orca, Climeworks has yet to reveal how effective the technology has proven to be. But in extensive interviews, top executives painted a picture of innovation in progress.

Chief marketing officer Julie Gosalvez told me that Orca is small and climatically insignificant on purpose. The goal is not to make a dent in climate change — yet — but to maximize learning at minimal cost. “You want to learn when you're small, right?” Gosalvez said. “It’s really de-risking the technology. It’s not like Tesla doing EVs when we have been building cars for 70 years and the margin of learning and risk is much smaller. It’s completely new.”

From the ground, Orca looks sort of like a warehouse or a server farm with a massive air conditioning system out back. The plant consists of eight shipping container-sized boxes arranged in a U-shape around a central building, each one equipped with an array of fans. When the plant is running, which is more or less all the time, the fans suck air into the containers where it makes contact with a porous filter known as a “sorbent” which attracts CO2 molecules.

When the filters become totally saturated with CO2, the vents on the containers snap shut, and the containers are heated to more than 212 degrees Fahrenheit. This releases the CO2, which is then delivered through a pipe to a secondary process called “liquefaction,” where it is compressed into a liquid. Finally, the liquid CO2 is piped into basalt rock formations underground, where it slowly mineralizes into stone. The process requires a little bit of electricity and a lot of heat, all of which comes from a carbon-free source — a geothermal power plant nearby.

A day at Orca begins with the morning huddle. The total number on the team is often in flux, but it typically has a staff of about 15 people, Climeworks’ head of operations Benjamin Keusch told me. Ten work in a virtual control room 1,600 miles away in Zurich, taking turns monitoring the plant on a laptop and managing its operations remotely. The remainder work on site, taking orders from the control room, repairing equipment, and helping to run tests.

During the huddle, the team discusses any maintenance that needs to be done. If there’s an issue, the control room will shut down part of the plant while the on-site workers investigate. So far, they’ve dealt with snow piling up around the plant that had to be shoveled, broken and corroded equipment that had to be replaced, and sediment build-up that had to be removed.

The air is more humid and sulfurous at the site in Iceland than in Switzerland, where Climeworks had built an earlier, smaller-scale model, so the team is also learning how to optimize the technology for different weather. Within all this troubleshooting, there’s additional trade-offs to explore and lessons to learn. If a part keeps breaking, does it make more sense to plan to replace it periodically, or to redesign it? How do supply chain constraints play into that calculus?

The company is also performing tests regularly, said Keusch. For example, the team has tested new component designs at Orca that it now plans to incorporate into Climeworks’ next project from the start. (Last year, the company began construction on “Mammoth,” a new plant that will be nine times larger than Orca, on a neighboring site.) At a summit that Climeworks hosted in June, co-founder Jan Wurzbacher said the company believes that over the next decade, it will be able to make its direct air capture system twice as small and cut its energy consumption in half.

“In innovation lingo, the jargon is we haven’t converged on a dominant design,” Gregory Nemet, a professor at the University of Wisconsin who studies technological development, told me. For example, in the wind industry, turbines with three blades, upwind design, and a horizontal axis, are now standard. “There were lots of other experiments before that convergence happened in the late 1980s,” he said. “So that’s kind of where we are with direct air capture. There’s lots of different ways that are being tried right now, even within a company like Climeworks."

Although Climeworks was willing to tell me about the goings-on at Orca over the last two years, the company declined to share how much carbon it has captured or how much energy, on average, the process has used.

Gosalvez told me that the plant’s performance has improved month after month, and that more detailed information was shared with investors. But she was hesitant to make the data public, concerned that it could be misinterpreted, because tests and maintenance at Orca require the plant to shut down regularly.

“Expectations are not in line with the stage of the technology development we are at. People expect this to be turnkey,” she said. “What does success look like? Is it the absolute numbers, or the learnings and ability to scale?”

Danny Cullenward, a climate economist and consultant who has studied the integrity of various carbon removal methods, did not find the company’s reluctance to share data especially concerning. “For these earliest demonstration facilities, you might expect people to hit roadblocks or to have to shut the plant down for a couple of weeks, or do all sorts of things that are going to make it hard to transparently report the efficiency of your process, the number of tons you’re getting at different times,” he told me.

But he acknowledged that there was an inherent tension to the stance, because ultimately, Climeworks’ business model — and the technology’s effectiveness as a climate solution — depend entirely on the ability to make precise, transparent, carbon accounting claims.

Nemet was also of two minds about it. Carbon removal needs to go from almost nothing today to something like a billion tons of carbon removed per year in just three decades, he said. That’s a pace on the upper end of what’s been observed historically with other technologies, like solar panels. So it’s important to understand whether Climeworks’ tech has any chance of meeting the moment. Especially since the company faces competition from a number of others developing direct air capture technologies, like Heirloom and Occidental Petroleum, that may be able to do it cheaper, or faster.

However, Nemet was also sympathetic to the position the company was in. “It’s relatively incremental how these technologies develop,” he said. “I have heard this criticism that this is not a real technology because we haven’t built it at scale, so we shouldn’t depend on it. Or that one of these plants not doing the removal that it said it would do shows that it doesn’t work and that we therefore shouldn’t plan on having it available. To me, that’s a pretty high bar to cross with a climate mitigation technology that could be really useful.”

More data on Orca is coming. Climeworks recently announced that it will work with the company Puro.Earth to certify every ton of CO2 that it removes from the atmosphere and stores underground, in order to sell carbon credits based on this service. The credits will be listed on a public registry.

But even if Orca eventually runs at full capacity, Climeworks will never be able to sell 4,000 carbon credits per year from the plant. Gosalvez clarified that 4,000 tons is the amount of carbon the plant is designed to suck up annually, but the more important number is the amount of “net” carbon removal it can produce. “That might be the first bit of education you need to get out there,” she said, “because it really invites everyone to look at what are the key drivers to be paid attention to.”

She walked me through a chart that illustrated the various ways in which some of Orca’s potential to remove carbon can be lost. First, there’s the question of availability — how often does the plant have to shut down due to maintenance or power shortages? Climeworks aims to limit those losses to 10%. Next, there’s the recovery stage, where the CO2 is separated from the sorbent, purified, and liquified. Gosalvez said it’s basically impossible to do this without losing some CO2. At best, the company hopes to limit that to 5%.

Finally, the company also takes into account “gray emissions,” or the carbon footprint associated with the business, like the materials, the construction, and the eventual decommissioning of the plant and restoration of the site to its former state. If one of Climeworks’ plants ever uses energy from fossil fuels (which the company has said it does not plan to do) it would incorporate any emissions from that energy. Climeworks aims to limit gray emissions to 15%.

In the end, Orca’s net annual carbon removal capacity — the amount Climeworks can sell to customers — is really closer to 3,000 tons. Gosalvez hopes other carbon removal companies adopt the same approach. “Ultimately what counts is your net impact on the planet and the atmosphere,” she said.

Get one great climate story in your inbox every day:

Despite being a first-of-its-kind demonstration plant — and an active research site — Orca is also a commercial project. In fact, Gosalvez told me that Orca’s entire estimated capacity for carbon removal, over the 12 years that the plant is expected to run, sold out shortly after it began operating. The company is now selling carbon removal services from its yet-to-be-built Mammoth plant.

In January, Climeworks announced that Orca had officially fulfilled orders from Microsoft, Stripe, and Shopify. Those companies have collectively asked Climeworks to remove more than 16,000 tons of carbon, according to the deal-tracking site cdr.fyi, but it’s unclear what portion of that was delivered. The achievement was verified by a third party, but the total amount removed was not made public.

Climeworks has also not disclosed how much it has charged companies per ton of carbon, a metric that will eventually be an important indicator of whether the technology can scale to a climate-relevant level. But it has provided rough estimates of how much it expects each ton of carbon removal to cost as the technology scales — expectations which seem to have shifted after two years of operating Orca.

In 2021, Climeworks co-founder Jan Wurzbacher said the company aimed to get the cost down to $200 to $300 per ton removed by the end of the decade, with steeper declines in subsequent years. But at the summit in June, he presented a new cost curve chart showing that the price was currently more than $1,000, and that by the end of the decade, it would fall to somewhere between $400 to $700. The range was so large because the cost of labor, energy, and storing the CO2 varied widely by location, he said. The company aims to get the price down to $100 to $300 per ton by 2050, when the technology has significantly matured.

Critics of carbon removal technologies often point to the vast sums flowing into direct air capture tech like Orca, which are unlikely to make a meaningful difference in climate change for decades to come. During a time when worsening disasters make action feel increasingly urgent, many are skeptical of the value of investing limited funds and political energy into these future solutions. Carbon removal won’t make much of a difference if the world doesn’t deploy the tools already available to reduce emissions as rapidly as possible — and there’s certainly not enough money or effort going into that yet.

But we’ll never have the option to fully halt climate change, let alone begin reversing it, if we don’t develop solutions like Orca. In September, the International Energy Agency released an update to its seminal net-zero report. The new analysis said that in the last two years, the world had, in fact, made significant progress on innovation. Now, some 65% of emission reductions after 2030 could be accounted for with technologies that had reached market uptake. It even included a line about the launch of Orca, noting that Climeworks’ direct air capture technology had moved from the prototype to the demonstration stage.

But it cautioned that DAC needs “to be scaled up dramatically to play the role envisaged,” in the net zero scenario. Climeworks’ experience with Orca offers a glimpse of how much work is yet to be done.

Read more about carbon removal:

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

The multi-faceted investment is defense-oriented, but could also support domestic clean energy.

MP Materials is the national champion of American rare earths, and now the federal government is taking a stake.

The complex deal, announced Thursday, involves the federal government acting as a guaranteed purchaser of MP Materials’ output, a lender, and also an investor in the company. In addition, the Department of Defense agreed to a price floor for neodymium-praseodymium products of $110 per kilogram, about $50 above its current spot price.

MP Materials owns a rare earths mine and processing facility near the California-Nevada border on the edges of the Mojave National Preserve. It claims to be “the largest producer of rare earth materials in the Western Hemisphere,” with “the only rare earth mining and processing site of scale in North America.”

As part of the deal, the company will build a “10X Facility” to produce magnets, which the DOD has guaranteed will be able to sell 100% of its output to some combination of the Pentagon and commercial customers. The DOD is also kicking in $150 million worth of financing for MP Materials’ existing processing efforts in California, alongside $1 billion from Wall Street — specifically JPMorgan Chase and Goldman Sachs — for the new magnet facility. The company described the deal in total as “a multi-billion-dollar commitment to accelerate American rare earth supply chain independence.”

Finally, the DOD will buy $400 million worth of newly issued stock in MP Materials, giving it a stake in the future production that it’s also underwriting.

Between the equity investment, the lending, and the guaranteed purchasing, the Pentagon, and by extension the federal government, has taken on considerable financial risk in casting its lot with a company whose primary asset’s previous owner went bankrupt a decade ago. But at least so far, Wall Street is happy with the deal: MP Materials’ market capitalization soared to over $7 billion on Thursday after its share price jumped over 40%, from a market capitalization of around $5 billion on Wednesday and the company is valued at around $7.5 billion as of Friday afternoon.

Despite the risk, former Biden administration officials told me they would have loved to make a deal like this.

When I asked Alex Jacquez, who worked on industrial policy for the National Economic Council in the Biden White House, whether he wished he could’ve overseen something like the DOD deal with MP Materials, he replied, “100%.” I put the same question to Ashley Zumwalt-Forbes, a former Department of Energy official who is now an investor; she said, “Absolutely.”

Rare earths and critical minerals were of intense interest to the Biden administration because of their use in renewable energy and energy storage. Magnets made with neodymium-praseodymium oxide are used in the electric motors found in EVs and wind turbines, as well as for various applications in the defense industry.

MP Materials will likely have to continue to rely on both sets of customers. Building up a real domestic market for the China-dominated industry will likely require both sets of buyers. According to a Commerce Department report issued in 2022, “despite their importance to national security, defense demand for … magnets is only a small portion of overall demand and insufficient to support an economically viable domestic industry.”

The Biden administration previously awarded MP Materials $58.5 million in 2024 through the Inflation Reduction Act’s 48C Advanced Energy Project tax credit to support the construction of a magnet facility in Fort Worth. While the deal did not come with the price guarantees and advanced commitment to purchase the facility’s output of the new agreement, GM agreed to come on as an initial buyer.

Matt Sloustcher, an MP Materials spokesperson, confirmed to me that the Texas magnet facility is on track to be fully up and running by the end of this year, and that other electric vehicle manufacturers could be customers of the new facility announced on Thursday.

At the time MP Materials received that tax credit award, the federal government was putting immense resources behind electric vehicles, which bolstered the overall supply supply chain and specifically demand for components like magnets. That support is now being slashed, however, thanks to the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which will cancel consumer-side subsidies for electric vehicle purchases.

While the Biden tax credit deal and the DOD investment have different emphases, they both follow on years of bipartisan support for MP Materials. In 2020, the DOD used its authority under the Defense Production Act to award almost $10 million to MP Materials to support its investments in mineral refining. At the time, the company had been ailing in part due to retaliatory tariffs from China, cutting off the main market for its rare earths. The company was shipping its mined product to China to be refined, processed, and then used as a component in manufacturing.

“Currently, the Company sells the vast majority of its rare earth concentrate to Shenghe Resources,” MP Materials the company said in its 2024 annual report, referring to a Chinese rare earths company.

The Biden administration continued and deepened the federal government’s relationship with MP Materials, this time complementing the defense investments with climate-related projects. In 2022, the DOD awarded a contract worth $35 million to MP Materials for its processing project in order to “enable integration of [heavy rare earth elements] products into DoD and civilian applications, ensuring downstream [heavy rare earth elements] industries have access to a reliable feedstock supplier.”

While the DOD deal does not mean MP Materials is abandoning its energy customers or focus, the company does appear to be to the new political environment. In its February earnings release, the company mentioned “automaker” or “automotive-grade magnets” four times; in its May earnings release, that fell to zero times.

Former Biden administration officials who worked on critical minerals and energy policy are still impressed.

The deal is “a big win for the U.S. rare earths supply chain and an extremely sophisticated public-private structure giving not just capital, but strategic certainty. All the right levers are here: equity, debt, price floor, and offtake. A full-stack solution to scale a startup facility against a monopoly,” Zumwalt-Forbes, the former Department of Energy official, wrote on LinkedIn.

While the U.S. has plentiful access to rare earths in the ground, Zumwalt-Forbes told me, it has “a very underdeveloped ability to take that concentrate away from mine sites and make useful materials out of them. What this deal does is it effectively bridges that gap.”

The issue with developing that “midstream” industry, Jacquez told me, is that China’s world-leading mining, processing, and refining capacity allows it to essentially crash the price of rare earths to see off foreign competitors and make future investment in non-Chinese mining or processing unprofitable. While rare earths are valuable strategically, China’s whip hand over the market makes them less financially valuable and deters investment.

“When they see a threat — and MP is a good example — they start ramping up production,” he said. Jacquez pointed to neodymium prices spiking in early 2022, right around when the Pentagon threw itself behind MP Materials’ processing efforts. At almost exactly the same time, several state-owned Chinese rare earth companies merged. Neodymium-praseodymium oxide prices fell throughout 2022 thanks to higher Chinese production quotas — and continued to fall for several years.

While the U.S. has plentiful access to rare earths in the ground, Zumwalt-Forbes told me, it has “a very underdeveloped ability to take that concentrate out away from mine sites and make useful materials out of them. What this deal does is it effectively bridges that gap.”

The combination of whipsawing prices and monopolistic Chinese capacity to process and refine rare earths makes the U.S.’s existing large rare earth reserves less commercially viable.

“In order to compete against that monopoly, the government needed to be fairly heavy handed in structuring a deal that would both get a magnet facility up and running and ensure that that magnet facility stays in operation and weathers the storm of Chinese price manipulation,” Zumwalt-Forbes said.

Beyond simply throwing money around, the federal government can also make long-term commitments that private companies and investors may not be willing or able to make.

“What this Department of Defense deal did is, yes, it provided much-needed cash. But it also gave them strategic certainty around getting that facility off the ground, which is almost more important,” Zumwalt-Forbes said.

“I think this won’t be the last creative critical mineral deal that we see coming out of the Department of Defense,” Zumwalt-Forbes added. They certainly are in pole position here, as opposed to the other agencies and prior administrations.”

On a new plan for an old site, tariffs on Canada, and the Grain Belt Express

Current conditions: Phoenix will “cool” to 108 degrees Fahrenheit today after hitting 118 degrees on Thursday, its hottest day of the year so far • An extreme wildfire warning is in place through the weekend in Scotland • University of Colorado forecasters decreased their outlook for the 2025 hurricane season to 16 named storms, eight hurricanes, and three major hurricanes after a quiet June and July.

President Trump threatened a 35% tariff on Canadian imports on Thursday, giving Prime Minister Mark Carney a deadline of August 1 before the levies would go into effect. The move follows months of on-again, off-again threats against Canada, with former Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau having successfully staved off the tariffs during talks in February. Despite those earlier negotiations, Trump held firm on his 50% tariff on steel and aluminum, which will have significant implications for green manufacturing.

As my colleagues Matthew Zeitlin and Robinson Meyer have written, tariffs on Canadian imports will affect the flow of oil, minerals, and lumber, as well as possibly break automobile supply chains in the United States. It was unclear as of Thursday, however, whether Trump’s tariffs “would affect all Canadian goods, or if he would follow through,” The New York Times reports. The move follows Trump’s announcement this week of tariffs on several other significant trade partners like Japan and South Korea, as well as a 50% tariff on copper.

The long beleaguered Lava Ridge Wind Project, formally halted earlier this year by an executive order from President Trump, might have a second life as the site for small modular reactors, Idaho News 6 reports. Sawtooth Energy Development Corporation has proposed installing six small nuclear power generators on the former Lava Ridge grounds in Jerome County, Idaho, drawn to the site by the power transmission infrastructure that could connect the region to the Midpoint Substation and onto the rest of the Western U.S. The proposed SMR project would be significantly smaller in scale than Lava Ridge, which would have produced 1,000 megawatts of electricity on a 200,000-acre footprint, sitting instead on 40 acres and generating 462 megawatts, enough to power 400,000 homes.

Sawtooth Energy plans to hold four public meetings on the proposal beginning July 21. The Lava Ridge Wind Project had faced strong local opposition — we named it the No. 1 most at-risk project of the energy transition last fall — due in part to concerns about the visibility of the turbines from the Minidoka National Historic Site, the site of a Japanese internment camp.

Get Heatmap AM directly in your inbox every morning:

Republican Senator Josh Hawley of Missouri said on social media Thursday that Energy Secretary Chris Wright had assured him that he will be “putting a stop to the Grain Belt Express green scam.” The Grain Belt Express is an 804-mile-long, $11 billion planned transmission line that would connect wind farms in Kansas to energy consumers in Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana, which has been nearing construction after “more than a decade of delays,” The New York Times reports. But earlier this month, Missouri Attorney General Andrew Bailey, a Republican, put in a request for the local public service commission to reconsider its approval, claiming that the project had overstated the number of jobs it would create and the cost savings for customers. Hawley has also been a vocal critic of the project and had asked the Energy Department to cancel its conditional loan guarantee for the transmission project.

New electric vehicles sold in Europe are significantly more environmentally friendly than gas cars, even when battery production is taken into consideration, according to a new study by the International Council on Clean Transportation. Per the report, EVs produce 73% less life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions than combustion engine cars, even considering production — a 24% improvement over 2021 estimates. The gains are also owed to the large share of renewable energy sources in Europe, and factor in that “cars sold today typically remain on the road for about 20 years, [and] continued improvement of the electricity mix will only widen the climate benefits of battery electric cars.” The gains are exclusive to battery electric cars, however; “other powertrains, including hybrids and plug-in hybrids, show only marginal or no progress in reducing their climate impacts,” the report found.

With the United Kingdom staring down its third heatwave in a month this week, a new study warns of dire consequences if homes and cities do not adapt to the new climate reality. According to researchers at the University College London and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, heat-related deaths in England and Wales could rise 50-fold by the 2070s, jumping from a baseline of 634 deaths to 34,027 in a worst-case scenario of 4.3 degrees Celsius warming, a high-emissions pathway.

The report specifically cited the aging populations of England and Wales, as older people become more vulnerable to the impacts of extreme heat. Low adoption of air conditioning is also a factor: only 2% to 5% of English households use air conditioning, although that number may grow to 32% by 2050. “We can mitigate [the] severity” of the health impacts of heat “by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and with carefully planned adaptations, but we have to start now,” UCL researcher Clare Heaviside told Sky News.

This week, Centerville, Ohio, rolled out high-tech recycling trucks that will use AI to scan the contents of residents’ bins and flag when items have been improperly sorted. “Reducing contamination in our recycling system lowers processing costs and improves the overall efficiency of our collection,” City Manager Wayne Davis said in a statement about the AI pilot program, per the Dayton Daily News.

Or at least the team at Emerald AI is going to try.

Everyone’s worried about the ravenous energy needs of AI data centers, which the International Energy Agency projects will help catalyze nearly 4% growth in global electricity demand this year and next, hitting the U.S. power sector particularly hard. On Monday, the Department of Energy released a report adding fuel to that fire, warning that blackouts in the U.S. could become 100 times more common by 2030 in large part due to data centers for AI.

The report stirred controversy among clean energy advocates, who cast doubt on that topline number and thus the paper’s justification for a significant fossil fuel buildout. But no matter how the AI revolution is powered, there’s widespread agreement that it’s going to require major infrastructure development of some form or another.

Not so fast, says Emerald AI, which emerged from stealth last week with $24.5 million in seed funding led by Radical Ventures along with a slew of other big name backers, including Nvidia’s venture arm as well as former Secretary of State John Kerry, Google’s chief scientist Jeff Dean, and Kleiner Perkins chair John Doerr. The startup, founded and led by Orsted’s former chief strategy and innovation officer Varun Sivaram, was built to turn data centers from “grid liabilities into flexible assets” by slowing, pausing, or redirecting AI workloads during times of peak energy demand.

Research shows this type of data center load flexibility could unleash nearly 100 gigawatts of grid capacity — the equivalent of four or five Project Stargates and enough to power about 83 million U.S. homes for a year. Such adjustments, Sivaram told me, would be necessary for only about 0.5% of a data center’s total operating time, a fragment so tiny that he says it renders any resulting training or operating performance dips for AI models essentially negligible.

As impressive as that hypothetical potential is, whether a software product can actually reduce the pressures facing the grid is a high stakes question. The U.S. urgently needs enough energy to serve that data center growth, both to ensure its economic competitiveness and to keep electricity bills affordable for Americans. If an algorithm could help alleviate even some of the urgency of an unprecedented buildout of power plants and transmission infrastructure, well, that’d be a big deal.

While Emerald AI will by no means negate the need to expand and upgrade our energy system, Sivaram told me, the software alone “materially changes the build out needs to meet massive demand expansion,” he said. “It unleashes energy abundance using our existing system.”

Grand as that sounds, the fundamental idea is nothing new. It’s the same concept as a virtual power plant, which coordinates distributed energy resources such as rooftop solar panels, smart thermostats, and electric vehicles to ramp energy supply either up or down in accordance with the grid’s needs.

Adoption of VPPs has lagged far behind their technical potential, however. That’s due to a whole host of policy, regulatory, and market barriers such as a lack of state and utility-level rules around payment structures, insufficient participation incentives for customers and utilities, and limited access to wholesale electricity markets. These programs also depend on widespread customer opt-in to make a real impact on the grid.

“It’s really hard to aggregate enough Nest thermostats to make any kind of dent,”” Sivaram told me. Data centers are different, he said, simply because “they’re enormous, they’re a small city.” They’re also, by nature, virtually controllable and often already interconnected if they’re owned by the same company. Sivaram thinks the potential of flexible data center loads is so promising and the assets themselves so valuable that governments and utilities will opt to organize “bespoke arrangements for data centers to provide their services.”

Sivaram told me he’s also optimistic that utilities will offer data center operators with flexible loads the option to skip the ever-growing interconnection queue, helping hyperscalers get online and turn a profit more quickly.

The potential to jump the queue is not something that utilities have formally advertised as an option, however, although there appears to be growing interest in the idea. An incentive like this will be core to making Emerald AI’s business case work, transmission advocate and president of Grid Strategies Rob Gramlich told me.

Data center developers are spending billions every year on the semiconductor chips powering their AI models, so the typical demand response value proposition — earn a small sum by turning off appliances when the grid is strained — doesn’t apply here. “There’s just not anywhere near enough money in that for a hyperscaler to say, Oh yeah, I’m gonna not run my Nvidia chips for a while to make $200 a megawatt hour. That’s peanuts compared to the bazillions [they] just spent,” Gramlich explained.

For Emerald AI to make a real dent in energy supply and blunt the need for an immediate and enormous grid buildout, a significant number of data center operators will have to adopt the platform. That’s where the partnership with Nvidia comes in handy, Sivaram told me, as the startup is “working with them on the reference architecture” for future AI data centers. “The goal is for all [data centers] to be potentially flexible in the future because there will be a standard reference design,” Sivaram said.

Whether or not data centers will go all in on Nvidia’s design remains to be seen, of course. Hyperscalers have not typically thought of data centers as a flexible asset. Right now, Gramlich said, most are still in the mindset that they need to be operating all 8,760 hours of the year to reach their performance targets.

“Two or three years ago, when we first noticed the surge in AI-driven demand, I talked to every hyperscaler about how flexible they thought they could be, because it seemed intuitive that machine learning might be more flexible than search and streaming,” Gramlich told me. By and large, the response was that while these companies might be interested in exploring flexibility “potentially, maybe, someday,” they were mostly focused on their mandate to get huge amounts of gigawatts online, with little time to explore new data center models.

“Even the ones that are talking about flexibility now, in terms of what they’re actually doing in the market today, they all are demanding 8,760 [hours of operation per year],” Gramlich told me.

Emerald AI is well aware that its business depends on proving to hyperscalers that a degree of flexibility won’t materially impact their operations. Last week, the startup released the results of a pilot demonstration that it ran at an Oracle data center in Phoenix, which proved it was able to reduce power consumption by 25% for three hours during a period of grid stress while still “assuring acceptable customer performance for AI workloads.”

It achieved this by categorizing specific AI tasks — think everything from model training and fine tuning to conversations with chatbots — from high to low priority, indicating the degree to which operations could be slowed while still meeting Oracle’s performance targets. Now, Emerald AI is planning additional, larger-scale demonstrations to showcase its capacity to handle more complex scenarios, such as responding to unexpected grid emergencies.

As transmission planners and hyperscalers alike wait to see more proof validating Emerald AI’s vision of the future, Sivaram is careful to note that his company is not advocating for a halt to energy system expansion. In an increasingly electrified economy, expanding and upgrading the grid will be essential — even if every data center in the world has a flexible load profile.

’We should be building a nationwide transmission system. We should be building out generation. We should be doing grid modernization with grid enhancing technologies,” Sivaram told me. “We just don’t need to overdo it. We don’t need the particularly massive projections that you’re seeing that are going to cause your grandmother’s electricity rates to spike. We can avoid that.”