You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

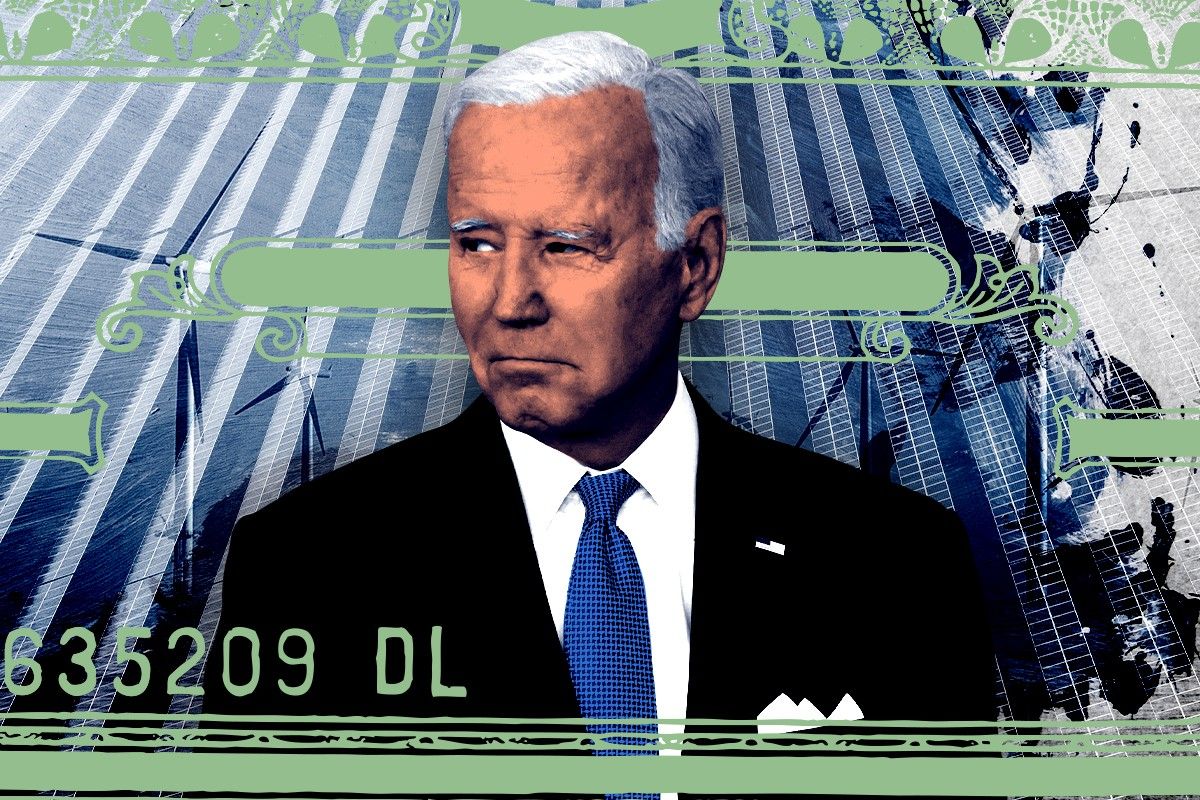

I caught up with Brett Christophers, the professor who argued in The New York Times that the Inflation Reduction Act is a gift to a secretive group of financial firms.

To the extent that they’re aware of it, American progressives are generally pretty happy with President Joe Biden’s flagship climate law, the Inflation Reduction Act.

The I.R.A. is slated to cut U.S. greenhouse-gas pollution up to 40% below its all-time high. It’s the centerpiece of Biden’s unprecedented experiment to revive industrial policy with a climate-friendly bent.

But what if it will have a tragic and unforeseen consequence? Earlier this week, Brett Christophers, a geography professor at Uppsala University in Sweden, argued in The New York Times that the I.R.A.’s green subsidies will backfire. The law will “accelerate the growing private ownership of U.S. infrastructure,” he warned, “dismantling” FDR’s legacy and leading to a “wholesale transformation of the national landscape of infrastructure ownership.”

Christophers is particularly worried that the law will enable a group of companies called “alternative asset managers,” who are the subject of his new book, Our Lives in Their Portfolios. These secretive firms own hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of highways, tunnels, water systems, and power plants worldwide, and Christophers argues that they wield a huge amount of control over our daily lives.

I am sympathetic to his argument — the creeping privatization of America’s roads, tunnels, and water systems is a big problem — but I am far less sure than he is that the I.R.A. will affect that trend. The climate law’s subsidies will mostly go to the energy and industrial sectors, and those parts of the economy are already overwhelmingly privately owned. For the first time ever, the I.R.A. includes “direct pay” subsidies that will allow governments and nonprofits to receive federal money when they build renewables.

I called Christophers to discuss his concerns about the I.R.A, why it might accelerate asset managers’ power, and what a better option might look like. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

So I was trying to make three arguments — and they span not just the book that’s just come out, but another book I’ve been working on about the political economy of the energy transition.

The first thing I was trying to get across in the piece is an argument about the growing influence of a particular set of financial institutions — asset-management institutions.

These are crucially not necessarily the types of asset managers that everyone talks about. Typically, the conversation is all about the BlackRocks, the Vanguards, the State Streets, which are the big holders of large proportions of basically every company that exists. Most of the funds that those big entities manage are passive index funds, which invest in proportion to the scale that companies represent within particular market indices. So if Exxon represents 1% of an index, then 1% of the fund is invested in Exxon, and so on. That's where most of the attention is focused.

What my book’s about is a completely different corner of the asset-management world, which are the active asset managers who increasingly own real assets. The ones I focus on in the book own housing of all shapes and sizes, and then everything that comes under the umbrella of infrastructure — transportation infrastructure, hospitals and schools, municipal water systems, and then all types of energy infrastructure. BlackRock dabbles in this, but the really big players are companies like Brookfield, Macquarie, and Blackstone.

My argument is that, actually, these are the guys that are much more consequential for people’s everyday lives. They determine what sort of condition these infrastructures are in — how much we pay in terms of water rates, or tenants pay in rents, or so on. These are the guys we should be focusing more on, but they’ve been kind of ignored.

Some of them are public, some are private. But even if they’re public, finding out much about what they’re doing is very difficult because all the investments occur through private funds domiciled in the Caymans or Delaware or Luxembourg. It’s a very, very secretive business.

So part of what I’m trying to do is literally just make people aware that these guys are out there and that energy is an important part of what they’re doing. [The asset manager] Brookfield, for example, probably has the fastest growing renewable portfolio in the world right now.

The second argument is that the approach that the world has right now to climate change — which is to put the energy transition in the private sector’s hands, albeit with subsidy and government-support mechanisms — is not working and will not work.

There’s various ways of substantiating that it’s not working. The International Energy Agency says that we need to go from $300 billion of clean-energy investment to $1.3 trillion straight away, and keep it there for the next decade. And it’s increasing now, but only in $50 billion a year chunks, rather than what we need.

And that’s because at root, renewable energy — the ownership and operation of renewable-energy-generating facilities — is actually just not a great business in terms of profitability. Their revenues and profits are very volatile because of the volatility of electricity prices. And if you talk to not only renewable developers, but also the people that finance new solar and wind facilities — the banks that put up the $300 million to buy the turbines — then you hear that the volatility of [electricity] pricing exerts a very kind of chilling effect on investment.

So when everyone obsesses about the fact that renewables are now cheaper than conventional generation, they’re looking at the wrong metric. Price is not what we should be looking at, profit is. And these businesses are just not very profitable.

So then the third argument is that of all the private-sector actors, asset managers are the very worst to rely on. They are particularly inappropriate owners of essential infrastructure that society relies on.

To cut a long story short, a basic reason is that the investment that Macquarie and Brookfield undertake is through investment vehicles that have a fixed-term life.

Yeah. When they buy these infrastructure assets, the only thing they’re thinking about is how they can sell them quickly, so that they can return the capital to the pension fund that gave them the money to invest in the first place. Because of the way the industry works, they’re disincentivized to carry out long-term capital expenditure — there’s inherent short-termism.

I was trying to compress all these things into the piece, which I obviously failed to do, but to the extent that it gets people talking about these problems, then I feel like I’ve succeeded.

That’s a good question. My basic answer is that the word “‘accelerate” is a very important one. As you’re no doubt aware, specifically in the energy realm, in energy-generating facilities, it’s not like privatization is a new thing there, right?

This has been going on for a long time. I guess it comes back to a strong belief I have, which is that the ongoing and accelerated privatization of these types of assets is generally not a good thing.

I would say two things to that. The first is that, we’ve obviously been at an important conjuncture in the U.S. for the last couple years, where the existing [renewable and EV] credits were being wound down. At the same time, there were proposals for a Green New Deal on the national level. So it felt like there was a possibility — arguably even the last possibility — of a different political economy of energy. So in a way, the IRA hammered the nail in the coffin of a substantially different future.

Second, in many other countries, energy has been more publicly owned than it is in the U.S. And the experience of other sectors and other parts of the world shows that the more you concentrate ownership in the hands of private entities, the more that those players increase their capacity to dictate the terms of what’s going on in the sector. They can influence — if not decide — the way that markets are constructed in the sector. You only have to look at the work of the legal scholar Shelly Welton, who has shown how regional wholesale power markets in the U.S. are still dominated by fossil fuels. What we think of as neutral mechanisms of market operation, the algorithms that award capacity and so on, are shaped by particular interests.

I hear that. But I think it’s important to distinguish what I think from another high-profile criticism of the IRA. I very rarely look at Twitter because I don’t find it healthy, but one thing that I see there all the time is this blanket critique of the derisking of investment. [Derisking is a term for when the government takes on some downside risk from private companies in order to persuade them to make investments in something “good,” like renewables or EVs. -Robinson]

That’s not my position at all. Give me a choice between derisking and not derisking, and from a climate perspective, I would always choose derisking. I would much rather the investment happens and Blackrock makes a killing than the investment doesn’t happen and we get stuck with fossil fuels.

To me, that’s not the choice. I think the blanket critique of derisking is naive in the sense that it either magically assumes we’re going to get state ownership of energy, or that the investment will happen anyway without the derisking. My whole book coming out next year is a critique of that argument, because the investment won’t happen. It absolutely won’t happen if you don’t derisk because of the profit constraints. You absolutely need that derisking.

My argument is that even with all of the support from various tax credits, and even with the historic — and amazing — reduction in [renewable] technology costs over the last 20 years, the private sector is still failing. That’s my argument. That’s why I believe we’re not going to reach where we need to be as long as we stick with this capital-centric model. But if you assume that we’re stuck with a private-sector-led model, then absolutely the IRA is a good thing, absolutely it is. You need that subsidization; I don’t disagree with that at all. Does that make sense?

Exactly.

You’ll get that, and I think you’ll get a modest amount of public-sector involvement, but in the big scheme of things I think it’ll be trivial. I think it will still amount to a transition that’s so much slower than we need.

For sure. If it wasn’t for direct pay, it would’ve been a nonstarter. I totally believe that.

I think that’s fair. I guess I would put it a slightly different way. I think I’m comparing it to a counterfactual under which we — by which I mean globally, but also within the U.S. — build renewables at something closer to the rate that is needed. So the IRA amounts, politically, within the U.S. context, to a degree of success, but it’s a degree of success within a framework that is failing.

I totally understand that. I think it comes down to what one’s counterfactual is. If your counterfactual is what was genuinely politically feasible in the U.S. context, then I can totally see that the IRA constitutes a significant success.

If your counterfactual is — and this may sound completely stupid — a situation in which we make really significant, genuine progress on changing what I see as the failing macro approach to the energy transition, then it doesn’t constitute success.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

On gas turbine backorders, Europe’s not-so-green deal, and Iranian cloud seeding

Current conditions: Up to 10 inches of rain in the Cascades threatens mudslides, particularly in areas where wildfires denuded the landscape of the trees whose roots once held soil in place • South Africa has issued extreme fire warnings for Northern Cape, Western Cape, and Eastern Cape • Still roiling from last week’s failed attempt at a military coup, Benin’s capital of Cotonou is in the midst of a streak of days with temperatures over 90 degrees Fahrenheit and no end in sight.

Exxon Mobil Corp. plans to cut planned spending on low-carbon projects by a third, joining much of the rest of its industry in refocusing on fossil fuels. The nation’s largest oil producer said it would increase its earnings and cash flow by $5 billion by 2030. The company projected earnings to grow by 13% each year without any increase in capital spending. But the upstream division, which includes exploration and production, is expected to bring in $14 billion in earnings growth compared to 2024. The key projects The Wall Street Journal listed in the Permian Basin, Guyana and at liquified natural gas sites would total $4 billion in earnings growth alone over the next five years. The announcement came a day before the Department of the Interior auctioned off $279 million of leases across 80 million acres of federal waters in the Gulf of Mexico.

Speaking of oil and water, early Wednesday U.S. armed forces seized an oil tanker off the coast of Venezuela in what The New York Times called “a dramatic escalation in President Trump’s pressure campaign against Nicolás Maduro.” When asked what would become of the vessel's oil, Trump said at the White House, “Well, we keep it, I guess.”

The Federal Reserve slashed its key benchmark interest rate for the third time this year. The 0.25 percentage point cut was meant to calibrate the borrowing costs to stay within a range between 3.5% and 3.75%. The 9-3 vote by the central bank’s board of governors amounted to what Wall Street calls a hawkish cut, a move to prop up a cooling labor market while signaling strong concerns about future downward adjustments that’s considered so rare CNBC previously questioned whether it could be real. But it’s good news for clean energy. As Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote after the September rate cut, lower borrowing costs “may provide some relief to renewables developers and investors, who are especially sensitive to financing costs.” But it likely isn’t enough to wipe out the effects of Trump’s tariffs and tax credit phaseouts.

GE Vernova plans to increase its capacity to manufacture gas turbines by 20 gigawatts once assembly line expansions are completed in the middle of next year. But in a presentation to investors this week, the company said it’s already sold out of new gas turbines all the way through 2028, and has less than 10 gigawatts of equipment left to sell for 2029. It’s no wonder supersonic jet startups, as I wrote about in yesterday’s newsletter, are now eyeing a near-term windfall by getting into the gas turbine business.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

The European Union will free more than 80% of the companies from environmental reporting rules under a deal struck this week. The agreement between EU institutions marks what Politico Europe called a “major legislative victory” for European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, who has sought to make the bloc more economically self-sufficient by cutting red tape for business in her second term in office. The rollback is also a win for Trump, whose administration heavily criticized the EU’s green rules. It’s also a victory for the U.S. president’s far-right allies in Europe. The deal fractured the coalition that got the German politician reelected to the EU’s top job, forcing her center-right faction to team up with the far right to win enough votes for secure victory.

Ravaged by drought, Iran is carrying out cloud-seeding operations in a bid to increase rainfall amid what the Financial Times clocked as “the worst water crisis in six decades.” On Tuesday, Abbas Aliabadi, the energy minister, said the country had begun a fresh round of injecting crystals into clouds using planes, drones, and ground-based launchers. The country has even started developing drones specifically tailored to cloud seeding.

The effort comes just weeks after the Islamic Republic announced that it “no longer has a choice” but to move its capital city as ongoing strain on water supplies and land causes Tehran to sink by nearly one foot per year. As I wrote in this newsletter, Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian called the situation a “catastrophe” and “a dark future.”

The end of suburban kids whiffing diesel exhaust in the back of stuffy, rumbling old yellow school buses is nigh. The battery-powered bus startup Highland Electric Fleets just raised $150 million in an equity round from Aiga Capital Partners to deploy its fleets of buses and trucks across the U.S., Axios reported. In a press release, the company said its vehicles would hit the streets by next year.

Cities across the state are adopting building codes that heavily incentivize homeowners to make the switch.

A quiet revolution in California’s building codes could turn many of the state’s summer-only air conditioners into all-season heat pumps.

Over the past few months, 12 California cities have adopted rules that strongly incentivize homeowners who are installing central air conditioning or replacing broken AC systems to get energy-efficient heat pumps that provide both heating and cooling. Households with separate natural gas or propane furnaces will be allowed to retain and use them, but the rules require that the heat pump becomes the primary heating system, with the furnace providing backup heat only on especially cold days, reducing fossil fuel use.

These “AC2HP” rules, as proponents call them, were included in a routine update of California building codes in 2024. Rather than make it mandatory, regulators put the heat pump rule in a package of “stretch codes” that cities could adopt as they saw fit. Moreno Valley, a city in Riverside County, east of Los Angeles, was the first to pass an ordinance adopting the AC2HP code back in August. A steady stream of cities have followed, with Los Gatos and Portola Valley joining the party just last week. Dylan Plummer, a campaign advisor for Sierra Club's Building Electrification Campaign, expects more will follow in the months to come — “conversations are moving” in Los Angeles and Sacramento, as well, he told me.

“This is a consumer protection and climate policy in one,” he said. As California gets hotter, more households in the state are getting air conditioners for the first time. “Every time a household installs a one-way AC unit, it’s a missed opportunity to install a heat pump and seamlessly equip homes with zero-emission heating.”

This policy domino effect is not unlike what happened in California after the city of Berkeley passed an ordinance in 2019 that would have prohibited new buildings from installing natural gas. The Sierra Club and other environmental groups helped lead more than 70 cities to follow in Berkeley’s footsteps. Ultimately, a federal court overturned Berkeley’s ordinance, finding that it violated a law giving the federal government authority over appliance energy usage. Many of the other cities have since suspended their gas bans.

Since then, however, California has adopted state-wide energy codes that strongly encourage new buildings to be all-electric anyway. In 2023, more than 70% of requests for service lines from developers to Pacific Gas & Electric, the biggest utility in the state, were for new all-electric buildings. The AC2HP codes tackle the other half of the equation — decarbonizing existing buildings.

A coalition of environmental groups including the Sierra Club, Earthjustice, and the Building Decarbonization Coalition are working to seed AC2HP rules throughout the state, although it may not be easy as cost-of-living concerns grow more politically charged.

Even in some of the cities that have adopted the code, members of the public worried about the expense. In Moreno Valley, for instance, a comparatively low-income community, six out of the seven locals who spoke on the measure at a meeting in August urged elected officials to reject it, and not just because of cost — some were also skeptical of the technology.

In Glendale, a suburb of Los Angeles which has more socioeconomic diversity, all four commenters who spoke also urged the council to reject the measure. In addition to cost concerns, they questioned why the city would rush to do something like this when the state didn’t make it mandatory, arguing that the council should have held a full public hearing on the change.

In Menlo Park, on the other hand, which is a wealthy Silicon Valley suburb, all five speakers were in support of the measure, although each of them was affiliated with an environmental group.

Heat pumps are more expensive than air conditioners by a couple of thousands of dollars, depending on the model. With state and local incentives, the upfront cost can often be comparable. When you take into account the fact that you’re moving from using two appliances for heating and cooling to one, the equipment tends to be cheaper in the long run.

The impacts of heat pumps on energy bills are more complicated. Heat pumps are almost always cheaper to operate in the winter than furnaces that use propane or electric resistance. Compared to natural gas heating, though, it mostly depends on the relative cost of gas versus electricity. Low-income customers in California have access to lower electricity rates that make heat pumps more likely to pencil out. The state also recently implemented a new electricity rate scheme that will see utilities charge customers higher fixed fees and lower rates per kilowatt-hour of electricity used, which may also help heat pump economics.

Matthew Vespa, an senior attorney at Earthjustice described the AC2HP policy as a way to help customers “hedge against gas rates going up,” noting that gas prices are likely to rise as the U.S. exports more of the fuel as liquified natural gas, and also as gas companies lose customers. “It’s really a small incremental cost to getting an AC replaced with a lot of potential benefits.”

The AC2HP idea dates back to a 2021 Twitter thread by Nate Adams, a heat pump installer who goes by the handle “Nate the House Whisperer.” Adams proposed that the federal government should pay manufacturers to stop producing air conditioners and only produce heat pumps. Central heat pumps are exactly the same as air conditioners, except they provide heating in addition to cooling thanks to “a few valves or ~$100-300 in parts,” Adam said at the time.

The problem is, most homeowners and installers are either unfamiliar with the technology or skeptical of it. While heat pumps have been around for decades and are widespread in other parts of the world, especially in Asia, they have been slower to take off in the United States. One reason is the common misconception that they don’t work as well as furnaces for heating. Part of the issue is also that furnaces themselves are less expensive, so heat pumps are a tougher sell in the moment when someone’s furnace has broken down. Adams’ policy pitch would have given people no choice but to start installing heat pumps — even if they didn’t use them for heating — getting a key decarbonization technology into homes faster than any rebate or consumer incentive could, and getting the market better acquainted with the tech.

The idea gained traction quickly. An energy efficiency research and advocacy organization called CLASP published a series of reports looking at the potential cost and benefits, and a manufacturer-focused heat pump tax credit even made its way into a bill proposal from Senator Amy Klobuchar in the runup to the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. While rules that target California homeowners obviously won’t have the nation-wide effect that Adams’ would have, they still have the potential to send a strong market signal, considering California is the fifth largest economy in the world.

The AC2HP codes, which start going into effect next year, will help smooth the road to another set of building electrification rules that will apply in some parts of the state beginning in 2029. At that point, households in the Bay Area will be subject to new air quality standards that require all newly installed heating equipment to be zero-emissions — in other words, if a family’s furnace breaks down, they’ll have to replace it with a heat pump. State regulators are developing similar standards that would apply statewide starting in 2035. The AC2HP rule ensures that if that same family’s air conditioner breaks between now and then, they won’t end up with a new air conditioner, which would eventually become redundant.

The rule is just one of a bunch of new tools cities are using to decarbonize existing buildings. San Francisco, for example, adopted an even stricter building code in September that requires full, whole-home electrification when a building is undergoing a major renovation that includes upgrades to its mechanical systems. Many cities are also adopting an “electrical readiness” code that requires building owners to upgrade their electrical panels and add wiring for electric vehicle charging and induction stoves when they make additions or alterations to an existing building.

To be clear, homeowners in cities with AC2HP laws will not be forced to buy heat pumps. The code permits the installation of an air conditioner, but requires that it be supplemented with efficiency upgrades such as insulating air ducts and attics — which may ultimately be more costly than the heat pump route.

“I don’t think most people understand that these units exist, and they’re kind of plug and play with the AC,” said Vespa.

Current conditions: The Pacific Northwest’s second atmospheric river in a row is set to pour up to 8 inches of rain on Washington and Oregon • A snow storm is dumping up to 6 inches of snow from North Dakota to northern New York • Warm air is blowing northeastward into Central Asia, raising temperatures to nearly 80 degrees Fahrenheit at elevations nearly 2,000 feet above sea level.

Heatmap’s Jael Holzman had a big scoop last night: The three leading Senate Democrats on energy and permitting reform issues are a nay on passing the SPEED Act. In a joint statement shared exclusively with Jael, Senate Energy and Natural Resources ranking member Martin Heinrich, Environment and Public Works ranking member Sheldon Whitehouse, and Hawaii senator Brian Schatz pledged to vote against the bill to overhaul the National Environmental Policy Act unless the legislation is updated to include measures to boost renewable energy and transmission development. “We are committed to streamlining the permitting process — but only if it ensures we can build out transmission and cheap, clean energy. While the SPEED Act does not meet that standard, we will continue working to pass comprehensive permitting reform that takes real steps to bring down electricity costs,” the statement read. To get up to speed on the legislation, read this breakdown from Heatmap’s Emily Pontecorvo.

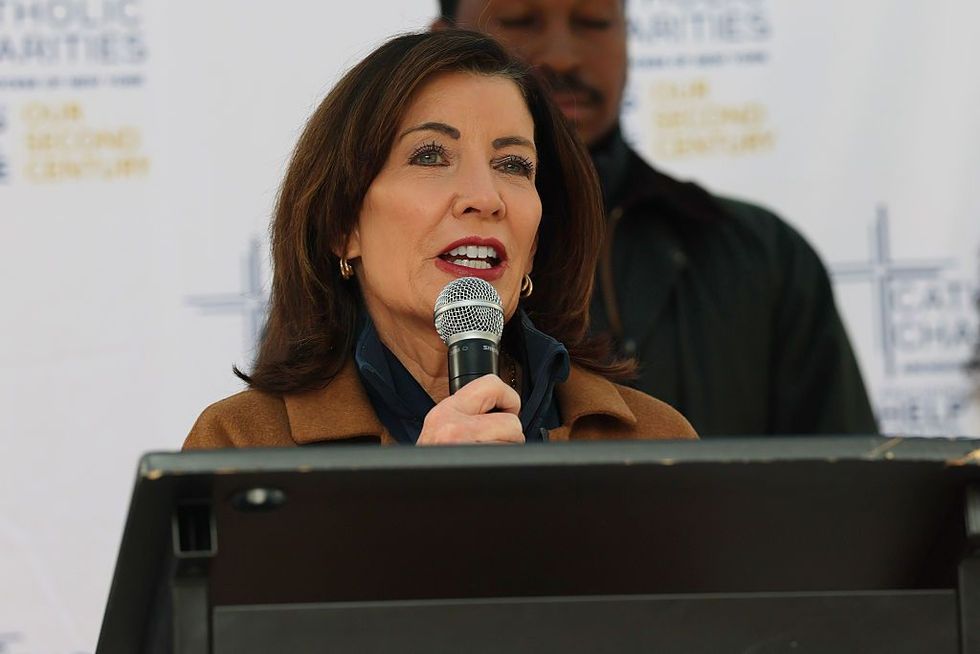

In June, Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin explained how New York State was attempting to overcome the biggest challenge to building a new nuclear plant — its deregulated electricity market — by tasking its state-owned utility with overseeing the project. It’s already begun staffing up for the nuclear project, as I reported in this newsletter. But it’s worth remembering that the New York Power Authority, the second-largest government-controlled utility in the U.S. after the federal Tennessee Valley Authority, gained a new mandate to invest in power plants directly again when the 2023 state budget passed with measures calling for public ownership of renewables. On Tuesday, NYPA’s board of trustees unanimously approved a list of projects in which the utility will take 51% ownership stakes in a bid to hasten construction of large-scale solar, wind, and battery facilities. The combined maximum output of all the projects comes to 5.5 gigawatts, nearly double the original target of 3 gigawatts set in January.

But that’s still about 25% below the 7 gigawatts NYPA outlined in its draft proposal in July. What changed? At a hearing Tuesday morning, NYPA officials described headwinds blowing from three directions: Trump’s phaseout of renewable tax credits, a new transmission study that identified which projects would cost too much to patch onto the grid, and a lack of power purchase agreements from offtakers. One or more of those variables ultimately led private developers to pull out at least 16 projects that NYPA would have co-owned.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

During World War II, the Lionel toy train company started making components for warships, the Ford Motor Company produced bomber planes, and the Mattatuck Manufacturing Company known for its upholstery nails switched to churning out cartridge clips for Springfield rifles. In a sign of how severe the shortfall of equipment to generate gas-powered electricity has become, would-be supersonic jet startups are making turbines. While pushing to legalize flights of the supersonic jets his company wants to build, Blake Scholl, the chief executive of Boom Supersonic, said he “kept hearing about how AI companies couldn’t get enough electricity,” and how companies such as ChatGPT-maker OpenAI “were building their own power plants with large arrays of converted jet engines.” In a thread on X, he said that, “under real world conditions, four of our Superpower turbines could do the job of seven legacy units. Without the cooling water required by legacy turbines!”

The gas turbine crisis, as Matthew wrote in September, may be moving into a new phase as industrial giants race to meet the surging demand. In general, investors have rewarded the effort. “But,” as Matthew posed, “what happens when the pressure to build doesn’t come from customers but from competitors?” We may soon find out.

It is, quite literally, the stuff of science fiction, the kind of space-based solar power plant that Isaac Asimov imagined back in 1940. But as Heatmap’s Katie Brigham reported in an exclusive this morning, the space solar company Overview Energy has emerged from stealth, announcing its intention to make satellites that will transmit energy via lasers directly onto Earth’s power grids. The company has raised $20 million in a seed round led by Lowercarbon Capital, Prime Movers Lab, and Engine Ventures, and is now working toward raising a Series A. The way the technology would work is by beaming the solar power to existing utility-scale solar projects. As Katie explained: “The core thesis behind Overview is to allow solar farms to generate power when the sun isn’t shining, turning solar into a firm, 24/7 renewable resource. What’s more, the satellites could direct their energy anywhere in the world, depending on demand. California solar farms, for example, could receive energy in the early morning hours. Then, as the sun rises over the West Coast and sets in Europe, ‘we switch the beam over to Western Europe, Morocco, things in that area, power them through the evening peak,’” Marc Berte, the founder and CEO of Overview Energy, told her. He added: “It hits 10 p.m., 11 p.m., most people are starting to go to bed if it’s a weekday. Demand is going down. But it’s now 3 p.m. in California, so you switch the beam back.”

In bigger fundraising news with more immediate implications for our energy system, next-generation geothermal darling Fervo Energy has raised another $462 million in a Series E round to help push its first power plants over the finish line, as Matthew wrote about this morning.

When Sanae Takaichi became the first Japanese woman to serve as prime minister in October, I told you at the time how she wanted to put surging energy needs ahead of lingering fears from Fukushima by turning the country’s nuclear plants back on and building more reactors. Her focus isn’t just on fission. Japan is “repositioning fusion energy from a distant research objective to an industrial priority,” according to The Fusion Report. And Helical Fusion has emerged as its national champion. The Tokyo-based company has signed the first power purchase agreement in Japan for fusion, a deal with the regional supermarket chain Aoki Super Co. to power some of its 50 stores. The Takaichi administration has signaled plans to increase funding for fusion as the new government looks to hasten its development. While “Japan still trails the U.S. and China in total fusion investment,” the trade newsletter reported, “the policy architecture now exists to close that gap rapidly.”

Another day, another emerging energy or climate technology gets Google’s backing. This morning, the carbon removal startup Ebb inked a deal with Google to suck 3,500 tons of CO2 out of the atmosphere. Ebb’s technology converts carbon dioxide from the air into “safe, durable” bicarbonate in seawater and converting “what has historically been a waste stream into a climate solution,” Ben Tarbell, chief executive of Ebb, said in a statement. “The natural systems in the ocean represent the most powerful and rapidly scalable path to meaningful carbon removal … Our ability to remove CO2 at scale becomes the natural outcome of smart business decisions — a powerful financial incentive that will drive expansion of our technology.”