You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

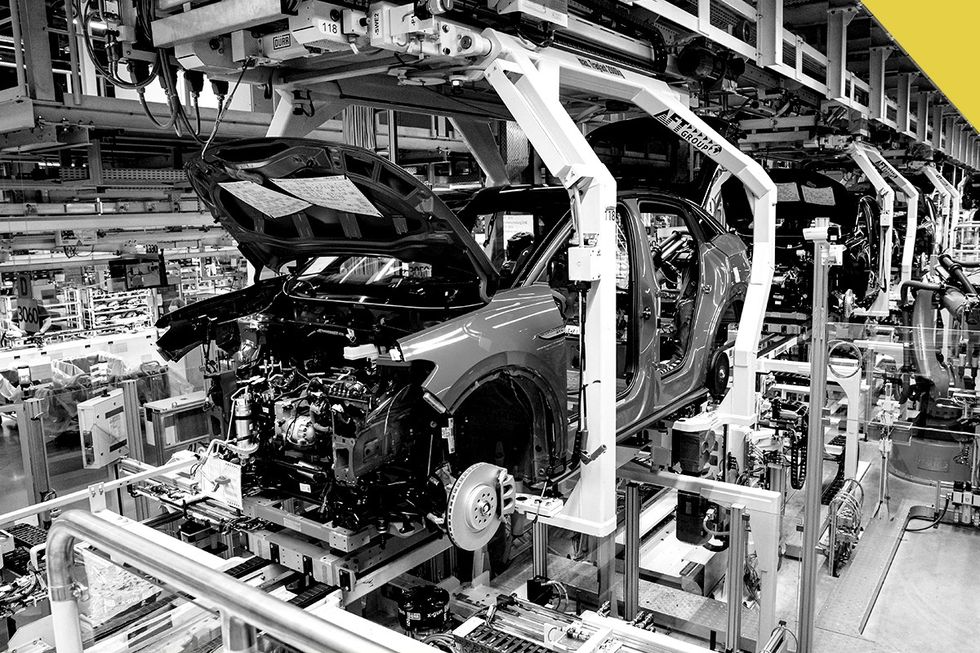

From what it means for America’s climate goals to how it might make American cars smaller again

The Biden administration just kicked off the next phase of the electric-vehicle revolution.

The Environmental Protection Agency unveiled Wednesday some of the world’s most aggressive climate rules on the transportation sector, a sweeping effort that aims to ensure that two-thirds of new cars, SUVs, and pickups — and one-quarter of new heavy-duty trucks — sold in the United States in 2032 will be all electric.

The rules, which are the most ambitious attempt to regulate greenhouse-gas pollution in American history, would put the country at the forefront of the global transition to electric vehicles. If adopted and enforced as proposed, the new standards could eventually prevent 10 billion tons of carbon pollution, roughly double America’s total annual emissions last year, the EPA says.

The rules would roughly halve carbon pollution from America’s massive car and truck fleet, the world’s third largest, within a decade. Such a cut is in line with Biden’s Paris Agreement goal of cutting carbon pollution from across the economy in half by 2030.

Transportation generates more carbon pollution than any other part of the U.S. economy. America’s hundreds of millions of cars, SUVs, pickups, 18-wheelers, and other vehicles generated roughly 25% of total U.S. carbon emissions last year, a figure roughly equal to the entire power sector’s.

In short, the proposal is a big deal with many implications. Here are seven of them.

Heatmap Illustration/Getty Images

Every country around the world must cut its emissions in half by 2030 in order for the world to avoid 1.5 degrees Celsius of temperature rise, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. That goal, enshrined in the Paris Agreement, is a widely used benchmark for the arrival of climate change’s worst impacts — deadly heat waves, stronger storms, and a near total die-off of coral reefs.

The new proposal would bring America’s cars and trucks roughly in line with that requirement. According to an EPA estimate, the vehicle fleet’s net carbon emissions would be 46% lower in 2032 than they stand today.

That means that rules of this ambition and stringency are a necessary part of meeting America’s goals under the Paris Agreement. The United States has pledged to halve its carbon emissions, as compared to its all-time high, by 2020. The country is not on track to meet that goal today, but robust federal, state, and corporate action — including strict vehicle rules — could help it get there, a recent report from the Rhodium Group, an energy-research firm, found.

Heatmap Illustration/Getty Images

Until this week, California and the European Union had been leading the world’s transition to electric vehicles. Both jurisdictions have pledged to ban sales of new fossil-fuel-powered cars after 2035 and set aggressive targets to meet that goal — although Europe recently watered down its commitment by allowing some cars to burn synthetic fuels.

The United States hasn’t issued a similar ban. But under the new rules, its timeline for adopting EVs will come close to both jurisdictions — although it may slightly lag California’s. By 2030, EVs will make up about 58% of new vehicles sold in Europe, according to the think tank Transportation & Environment; that is roughly in line with the EPA’s goals.

California, meanwhile, expects two-thirds of new car sales to be EVs by the same year, putting it ahead of the EPA’s proposal. The difference between California’s targets and the EPA’s may come down to technical accounting differences, however. The Washington Post has reported that the new EPA rules are meant to harmonize the national standards with California’s.

Heatmap Illustration/Getty Images

With or without the rules, the United States was already likely to see far more EVs in the future. Ford has said that it would aim for half of its global sales to be electric by 2030, and Stellantis, which owns Chrysler and Jeep, announced that half of its American sales and all its European sales must be all-electric by that same date. General Motors has pledged to sell only EVs after 2035. In fact, the EPA expects that automakers are collectively on track for 44% of vehicle sales to be electric by 2030 without any changes to emissions rules.

But every manufacturer is on a different timeline, and some weren’t planning to move quite this quickly. John Bozella, the president of Alliance for Automotive Innovation, has struck a skeptical note about the proposal. “Remember this: A lot has to go right for this massive — and unprecedented — change in our automotive market and industrial base to succeed,” he told The New York Times.

The proposed rules would unify the industry and push it a bit further than current plans suggest.

Heatmap Illustration/Getty Images

The EPA’s proposal would see sales of all-electric heavy trucks grow beginning with model year 2027. The agency estimates that by 2032, some 50% of “vocational” vehicles sold — like delivery trucks, garbage trucks, and cement mixers — will be zero-emissions, as well as 35% of short-haul tractors and 25% of long-haul tractor trailers. This would save about 1.8 billion tons of CO2 through 2055 — roughly equivalent to one year’s worth of emissions from the transportation sector.

But the proposal falls short of where the market is already headed, some environmental groups pointed out. “It’s not driving manufacturers to do anything,” said Paul Cort, director of Earthjustice’s Right to Zero campaign. “It’s following what’s happening in the market in a very conservative way.”

Last year, California passed rules requiring 60% of vocational truck sales and 40% of tractors to be zero-emissions by 2032. Daimler, the world’s largest truck manufacturer, has said that zero emissions trucks would make up 60% of its truck sales by 2030 and 100% by 2039. Volvo Trucks, another major player, said it aims for 50% of its vehicle deliveries to be electric by 2030.

Heatmap Illustration/Getty Images

One of the more interesting aspects of the new rules is that they pick up on a controversy that has been running on and off for the past 13 years.

In 2010, the Obama administration issued the first-ever greenhouse-gas regulations for light-duty cars, SUVs, and trucks. In order to avoid a Supreme Court challenge to the rules, the White House did something unprecedented: It got every automaker to agree to meet the standards even before they became law.

This was a milestone in the history of American environmental law. Because the automakers agreed to the rules, they were in effect conceding that the EPA had the legal authority to regulate their greenhouse-gas pollution in the first place. That shored up the EPA’s legal authority to limit greenhouse gases from any part of the economy, allowing the agency to move on to limiting carbon pollution from power plants and factories.

But that acquiescence came at a cost. The Obama administration agreed to what are called “vehicle footprint” provisions, which put its rules on a sliding scale based on vehicle size. Essentially, these footprint provisions said that a larger vehicle — such as a three-row SUV or full-sized pickup — did not have to meet the same standards as a compact sedan. What’s more, an automaker only had to meet the standards that matched the footprint of the cars it actually sold. In other words, a company that sold only SUVs and pickups would face lower overall requirements than one that also sold sedans, coupes, and station wagons.

Some of this decision was out of Obama’s hands: Congress had required that the Department of Transportation, which issues a similar set of rules, consider vehicle footprint in laws that passed in 2007 and 1975. Those same laws also created the regulatory divide between cars and trucks.

But over the past decade, SUV and truck sales have boomed in the United States, while the market for old-fashioned cars has withered. In 2019, SUVs outsold cars two to one; big SUVs and trucks of every type now make up nearly half the new car market. In the past decade, too, the crossover — a new type of car-like vehicle that resembles a light-duty truck — has come to dominate the American road. This has had repercussions not just for emissions, but pedestrian fatalities as well.

Researchers have argued that the footprint rules may be at least partially to blame for this trend. In 2018, economists at the University of Chicago and UC Berkeley argued Japan’s tailpipe rules, which also include a footprint mechanism, pushed automakers to super-size their cars. Modeling studies have reached the same conclusion about the American rules.

For the first time, the EPA’s proposal seems to recognize this criticism and tries to address it. The new rules make the greenhouse-gas requirements for cars and trucks more similar than they have been in the past, so as to not “inadvertently provide an incentive for manufacturers to change the size or regulatory class of vehicles as a compliance strategy,” the EPA says in a regulatory filing.

The new rules also tighten requirements on big cars and trucks so that automakers can’t simply meet the rules by enlarging their vehicles.

These changes may not reverse the trend toward larger cars. It might even reveal how much cars’ recent growth is driven by consumer taste: SUVs’ share of the new car market has been growing almost without exception since the Ford Explorer debuted in 1991. But it marks the first admission by the agency that in trying to secure a climate win, it may have accidentally created a monster.

Heatmap Illustration/Buenavista Images via Getty Images

The EPA is trumpeting the energy security benefits of the proposal, in addition to its climate benefits.

While the U.S. is a net exporter of crude — and that’s not expected to change in the coming decades — U.S. refineries still rely on “significant imports of heavy crude which could be subject to supply disruptions,” the agency notes. This reliance ties the U.S. to authoritarian regimes around the world and also exposes American consumers to wilder swings in gas prices.

But the new greenhouse gas rules are expected to severely diminish the country’s dependence on foreign oil. Between cars and trucks, the rules would cut crude oil imports by 124 million barrels per year by 2030, and 1 billion barrels in 2050. For context, the United States imported about 2.2 billion barrels of crude oil in 2021.

This would also be a turning point for gas stations. Americans consumed about 135 billion gallons of gasoline in 2022. The rules would cut into gas sales by about 6.5 billion gallons by 2030, and by more than 50 billion gallons by 2050. Gas stations are going to have to adapt or fade away.

Heatmap Illustration/Getty Images

Although it may seem like these new electric vehicles could tax our aging, stressed electricity grid, the EPA claims these rules won’t change the status quo very much. The agency estimates the rules would require a small, 0.4% increase in electricity generation to meet new EV demand by 2030 compared to business as usual, with generation needs increasing by 4% by 2050. “The expected increase in electric power demand attributable to vehicle electrification is not expected to adversely affect grid reliability,” the EPA wrote.

Still, that’s compared to the trajectory we’re already on. With or without these rules, we’ll need a lot of investment in new power generation and reliability improvements in the coming years to handle an electrifying economy. “Standards or no standards, we have to have grid operators preparing for EVs,” said Samantha Houston, a senior vehicles analyst at the Union of Concerned Scientists.

The reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from replacing gas cars will also far outweigh any emissions related to increased power demands. The EPA estimates that between now and 2055, the rules could drive up power plant pollution by 710 million metric tons, but will cut emissions from cars by 8 billion tons.

This article was last updated on April 13 at 12:37 PM ET.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

The cost crisis in PJM Interconnection has transcended partisan politics.

If “war is too important to be left to the generals,” as the French statesman Georges Clemenceau said, then electricity policy may be too important to be left up to the regional transmission organizations.

Years of discontent with PJM Interconnection, the 13-state regional transmission organization that serves around 67 million people, has culminated in an unprecedented commandeering of the system’s processes and procedures by the White House, in alliance with governors within the grid’s service area.

An unlikely coalition including Secretary of Energy Chris Wright, Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum, and the governors of Indiana, Ohio, Virginia, West Virginia, and Tennessee (Republicans), plus the governors of Maryland, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Illinois, Michigan, New Jersey, and North Carolina (Democrats) — i.e. all 13 states of PJM — signed a “Statement of Principles” Friday demanding extensive actions and reforms to bring new generation onto the grid while protecting consumers.

The plan envisions procuring $15 billion of new generation in the region with “revenue certainty” coming from data centers, “whether they show up and use the power or not,” according to a Department of Energy fact sheet. This would occur through what’s known as a “reliability backstop auction,” The DOE described this as a “an emergency procurement auction,” outside of the regular capacity auction where generation gets paid to be available on the grid when needed. The backstop auction would be for new generation to be built and to serve the PJM grid with payments spreading out over 15 years.

“We’re in totally uncharted waters here,” Jon Gordon, director of the clean energy trade group Advanced Energy United, told me, referring to the degree of direction elected officials are attempting to apply to PJM’s processes.

“‘Unprecedented,’ I feel, is a word that has lost all meaning. But I do think this is unprecedented,” Abraham Silverman, a Johns Hopkins University scholar who previously served as the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities’ general counsel, told me.

“In some ways, the biggest deal here is that they got 13 governors and the Trump administration to agree to something,” Silverman said. “I just don't think there's that many things that [Ohio] Governor [Mike] DeWine and or [Indiana] Governor [Mike] Braun agree with [Maryland] Governor [Wes] Moore.”

This document is “the death of the idea that PJM could govern itself,” Silverman told me. “PJM governors have had a real hands off approach to PJM since we transitioned into these market structures that we have now. And I think there was a real sense that the technocrats are in charge now, the governors can kind of step back and leave the PJM wrangling to the public service commissions.”

Those days are over.

The plan from the states and the White House would also seek to maintain price caps in capacity auctions, which Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro had previously obtained through a settlement. The statement envisions a reliability auction for generators to be held by September of this year, and requested that PJM make the necessary filings “expeditiously.”

Shapiro’s office said in a statement that the caps being maintained was a condition of his participation in the agreement, and that the cost limit had already saved consumers over $18 billion.

The Statement of Principles is clear that the costs of new generation procured in the auction should be allocated to data centers that have not “self-procured new capacity or agreed to be curtailable,” a reference to the increasingly popular idea that data centers can avoid increasing the peak demand on the system by reducing their power usage when the grid is stressed.

The dealmaking seems to have sidestepped PJM entirely, with a PJM spokesperson noting to Bloomberg Thursday evening that its representatives “ were not invited to the event they are apparently having” at the White House. PJM also told Politico that it wasn’t involved in the process.

“PJM is reviewing the principles set forth by the White House and governors,” the grid operator said in a statement to Heatmap.

PJM also said that it would be releasing its own long-gestating proposal to reform rules for large load interconnection, on which it failed to achieve consensus among its membership in November, on Friday.

“The Board has been deliberating on this issue since the end of that stakeholder process. We will work with our stakeholders to assess how the White House directive aligns with the Board’s decision,” the statement said.

The type of “backstop procurement” envisioned by the Statement of Principles sits outside of PJM’s capacity auctions, Jefferies analysts wrote in a note to clients, and “has been increasingly inevitable for months,” the note said.

While the top-down steering is precedent-breaking, any procurement within PJM will have to follow the grid’s existing protocols, which means submitting a plan and seeking signoff from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, Gordon told me. “Everything PJM does is guided by their tariffs and their manuals,” he said. “They follow those very closely.”

The governors of the PJM states have been increasingly vocal about how PJM operates, however, presaging today’s announcement. “Nobody really cared about PJM — or even knew what they PJM was or what they did — until electric prices reached a point where they became a political lightning rod,” Gordon said.

The Statement is also consistent with a flurry of announcements and policies issued by state governments, utility regulators, technology companies, and the White House this year coalescing around the principle that data centers should pay for their power such that they do not increase costs for existing users of the electricity system.

Grid Strategies President Rob Gramlich issued a statement saying that “the principle of new large loads paying their fair share is gaining consensus across states, industry groups, and political parties. The rules that have been in place for years did not ensure that.”

This $15 billion could bring on around 5.5 gigawatts of new capacity, according to calculations done by Jefferies. That figure would come close to the 6.6 gigawatts PJM fell short of its target reserve margin after its last capacity auction, conducted in December.

That auction hit the negotiated price caps and occasioned fierce criticism for how PJM manages its capacity markets. Several commissioners of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission have criticized PJM for its high capacity prices, low reserve margin, and struggles bringing on new generation. PJM’s Independent Market Monitor has estimated that planned and existing data center construction has added over $23 billion in costs to the system.

Several trade and advocacy groups pointed out, however, that a new auction does not fix PJM’s interconnection issues, which have become a major barrier to getting new resources, especially batteries, onto the grid in the PJM region. “The line for energy projects to connect to the power grid in the Mid-Atlantic has basically had a ‘closed for maintenance’ sign up for nearly four years now, and this proposal does nothing to fix that — or any of the other market and planning reforms that are long overdue,” AEU said in a statement.

The Statement of Principles includes some language on interconnection, asking PJM to “commit to rapidly deploying broader interconnection improvements” and to “achieving meaningful reductions in interconnection timelines,” but this language largely echoes what FERC has been saying since at least its Order No. 2023, which took effect over two years ago.

Climate advocacy group Evergreen Action issued a statement signed by Deputy Director of State Action Julia Kortrey, saying that “without fixing PJM’s broken interconnection process and allowing ready-to-build clean energy resources onto the grid, this deal could amount to little more than a band aid over a mortal wound.”

The administration’s language was predictably hostile to renewables and supportive of fossil fuels, blasting PJM for “misguided policies favored intermittent energy resources” and its “reliance on variable generation resources.” PJM has in fact acted to keep coal plants in its territory running, and has for years warned that “retirements are at risk of outpacing the construction of new resources,” as a PJM whitepaper put it in 2023.

There was a predictable partisan divide at the White House event around generation, with Interior Secretary Burgum blaming a renewables “fairy tale” for PJM’s travails. In a DOE statement, Burgum said “For too long, the Green New Scam has left Mid-Atlantic families in the dark with skyrocketing bills.”

Shapiro shot back that “anyone who stands up here and says we need one and not the other doesn’t have a comprehensive, smart energy dominance strategy — to use your word — that is going to ultimately create jobs, create more freedom and create more opportunity.”

While the partisan culture war over generation may never end, today’s announcement was more notable for the agreement it cemented.

“There is an emerging consensus that the political realities of operating a data center in this day and age means that you have to do it in a way that isn't perceived as big tech outsourcing its electric bill to grandma,” Silverman said.

Editor’s note: This article originally misidentified the political affiliation of the governor of Kentucky. It’s been corrected. We regret the error.

“Additionality” is back.

You may remember “additionality” from such debates as, “How should we structure the hydrogen tax credit?”

Well, it’s back, this time around Meta’s massive investment in nuclear power.

On January 9, the hyperscaler announced that it would be continuing to invest in the nuclear business. The announcement went far beyond its deal last year to buy power from a single existing plant in Illinois and embraced a smorgasbord of financial and operational approaches to nukes. Meta will buy the output for 20 years from two nuclear plants in Ohio, it said, including additional power from increased capacity that will be installed at the plants (as well as additional power from a nuclear plant in Pennsylvania), plus work on developing new, so-far commercially unproven designs from nuclear startups Oklo and TerraPower. All told, this could add up to 6.6 gigawatts of clean, firm power.

Sounds good, right?

Well, the question is how exactly to count that power. Over 2 gigawatts of that capacity is already on the grid from the two existing power plants, operated by Vistra. There will also be an “additional 433 megawatts of combined power output increases” from the existing power plants, known as “uprates,” Vistra said, plus another 3 gigawatts at least from the TerraPower and Oklo projects, which are aiming to come online in the 2030s

Princeton professor and Heatmap contributor Jesse Jenkins cried foul in a series of posts on X and LinkedIn responding to the deal, describing it as “DEEPLY PROBLEMATIC.”

“Additionality” means that new demand should be met with new supply from renewable or clean power. Assuming that Meta wants to use that power to serve additional new demand from data centers, Jenkins argued that “the purchase of 2.1 gigawatts of power … from two EXISTING nuclear power plants … will do nothing but increase emissions AND electricity rates” for customers in the area who are “already grappling with huge bill increases, all while establishing a very dangerous precedent for the whole industry.”

Data center demand is already driving up electricity prices — especially in the area where Meta is signing these deals. Customers in the PJM Interconnection electricity grid, which includes Ohio, have paid $47 billion to ensure they have reliable power over the grid operator’s last three capacity auctions. At least $23 billion of that is attributable to data center usage, according to the market’s independent monitor.

“When a huge gigawatt-scale data center connects to the grid,” Jenkins wrote, “it's like connecting a whole new city, akin to plopping down a Pittsburgh or even Chicago. If you add massive new demand WITHOUT paying for enough new supply to meet that growth, power prices spike! It's the simple law of supply & demand.”

And Meta is investing heavily in data centers within the PJM service area, including its Prometheus “supercluster” in New Albany, Ohio. The company called out this facility in its latest announcement, saying that the suite of projects “will deliver power to the grids that support our operations, including our Prometheus supercluster in New Albany, Ohio.”

The Ohio project has been in the news before and is planning on using 400 megawatts of behind-the-meter gas power. The Ohio Power Siting Board approved 200 megawatts of new gas-fired generation in June.

This is the crux of the issue for Jenkins: “Data centers must pay directly for enough NEW electricity capacity and energy to meet their round-the-clock needs,” he wrote. This power should be clean, both to mitigate the emissions impact of new demand and to meet the goals of hyperscalers, including Meta, to run on 100% clean power (although how to account for that is a whole other debate).

While hyperscalers like Meta still have clean power goals, they have been more sotto voce recently as the Trump administration wages war on solar and wind. (Nuclear, on the other hand, is very much administration approved — Secretary of Energy Chris Wright was at Meta’s event announcing the new nuclear deal.)

Microsoft, for example, mentioned the word “clean” just once in its Trump-approved “Building Community-First AI Infrastructure” manifesto, released Tuesday, which largely concerned how it sought to avoid electricity price hikes for retail customers and conserve water.

It’s not entirely clear that Meta views the entirety of these deals — the power purchase agreements, the uprates, financially supporting the development of new plants — as extra headroom to expand data center development right now. For one, Meta at least publicly claims to care about additionality. Meta’s own public-facing materials describing its clean energy commitments say that a “fundamental tenet of our approach to clean and renewable energy is the concept of additionality: partnering with utilities and developers to add new projects to the grid.”

And it’s already made substantial deals for new clean energy in Ohio. Last summer, Meta announced a deal with renewable developer Invenergy to procure some 440 megawatts of solar power in the state by 2027, for a total of 740 megawatts of renewables in Ohio. So Meta and Jenkins may be less far apart than they seem.

There may well be value in these deals from a sustainability and decarbonization standpoint — not to mention a financial standpoint. Some energy experts questioned Jenkins’ contention that Meta was harming the grid by contracting with existing nuclear plants.

“Based on what I know about these arrangements, they don’t see harm to the market,” Jeff Dennis, a former Department of Energy official who’s now executive director of the Electricity Customer Alliance, an energy buyers’ group that includes Meta, told me.

In power purchase agreements, he said, “the parties are contracting for price and revenue certainty, but then the generator continues to offer its supply into the energy and capacity markets. So the contracting party isn’t siphoning off the output for itself and creating or exacerbating a scarcity situation.”

The Meta deal stands in contrast to the proposed (and later scotched) deal between Amazon and Talen Energy, which would have co-located a data center at the existing Susquehanna nuclear plant and sucked capacity out of PJM.

Dennis said he didn’t think Meta’s new deals would have “any negative impact on prices in PJM” because the plants would be staying in the market and on the grid.

Jenkins praised the parts of the Meta announcement that were both clean and additional — that is, the deals with TerraPower and Oklo, plus the uprates from existing nuclear plants.

“That is a huge purchase of NEW clean supply, and is EXACTLY what hyperscalars [sic] and other large new electricity users should be doing,” Jenkins wrote. “Pay to bring new clean energy online to match their growing demand. That avoids raising rates for other electricity users and ensures new demand is met by new clean supply. Bravo!”

But Dennis argued that you can’t neatly separate out the power purchase agreement for the existing output of the plants and the uprates. It is “reasonable to assume that without an agreement that shores up revenues for their existing output and for maintenance and operation of that existing infrastructure, you simply wouldn't get those upgrades and 500 megawatts of upgrades,” he told me.

There’s also an argument that there’s real value — to the grid, to Meta, to the climate — to giving these plants 20 years of financial certainty. While investment is flooding into expanding and even reviving existing nuclear plants, they don’t always fare well in wholesale power markets like PJM, and saw a rash of plant retirements in the 2010s due to persistently low capacity and energy prices. While the market conditions are now quite different, who knows what the next 20 years might bring.

“From a pure first order principle, I agree with the additionality criticism,” Ethan Paterno, a partner at PA Consulting, an innovation advisory firm, told me. “But from a second or third derivative in the Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon, you can make the argument that the hyperscalers are keeping around nukes that perhaps might otherwise be retired due to economic pressure.”.

Ashley Settle, a Meta spokesperson, told me that the deals “enable the extension of the operational lifespan and increase of the energy production at three facilities.” Settle did not respond, however, when asked how Facebook would factor the deals into its own emissions accounting.

“The only way I see this deal as acceptable,” Jenkins wrote, “is if @Meta signed a PPA with the existing reactors only as a financial hedge & to help unlock the incremental capacity & clean energy from uprates at those plants, and they are NOT counting the capacity or energy attributes from the existing capacity to cover new data center demand.”

There’s some hint that Meta may preserve the additionality concept of matching only new supply with demand, as the announcement refers to “new additional uprate capacity,” and says that “consumers will benefit from a larger supply of reliable, always-ready power through Meta-supported uprates to the Vistra facilities.” The text also refers to “additional 20-year nuclear energy agreements,” however, which would likely not meet strict definitions of additionality as it refers to extending the lifetime and maintaining the output of already existing plants.

A third judge rejected a stop work order, allowing the Coastal Virginia offshore wind project to proceed.

Offshore wind developers are now three for three in legal battles against Trump’s stop work orders now that Dominion Energy has defeated the administration in federal court.

District Judge Jamar Walker issued a preliminary injunction Friday blocking the stop work order on Dominion’s Coastal Virginia offshore wind project after the energy company argued it was issued arbitrarily and without proper basis. Dominion received amicus briefs supporting its case from unlikely allies, including from representatives of PJM Interconnection and David Belote, a former top Pentagon official who oversaw a military clearinghouse for offshore wind approval. This comes after Trump’s Department of Justice lost similar cases challenging the stop work orders against Orsted’s Revolution Wind off the coast of New England and Equinor’s Empire Wind off New York’s shoreline.

As for what comes next in the offshore wind legal saga, I see three potential flashpoints:

It’s important to remember the stakes of these cases. Orsted and Equinor have both said that even a week or two more of delays on one of these projects could jeopardize their projects and lead to cancellation due to narrow timelines for specialized ships, and Dominion stated in the challenge to its stop work order that halting construction may cost the company billions.