You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

South of the border, Tesla quietly made its electric vehicles a little simpler.

The independent Tesla-tracking website Not A Tesla App recently shared news of a subtle change to the Tesla Model 3 that’s offered in Mexico compared to those for sale in the U.S. In place of the vegan faux leather that had been the sole option for its seats, Tesla offered ordinary cloth fabric as a choice. Luxury touches such as the heated or cooled seats aren’t available in this version of the Model 3. Nor is the rear touchscreen for backseat passengers to control their own temperature settings, a key addition to the redesigned Model 3 that recently debuted.

These changes don’t knock a lot off the cost of the EV: This rear-wheel drive 3 still costs 749,000 pesos, or about $40,000. But the introduction of a more stripped-down Tesla could be a signal that, just maybe, a more affordable Tesla is around the corner.

There’s no getting around it: Money may be the biggest stumbling block for EVs in the United States — at least as range anxiety dissipates thanks to better battery technology, growing charger networks, and people simply having more exposure to electric vehicles. The gap may be closing, but, in general, new EVs remain pricier than entry-level gas cars. Meanwhile, high interest rates are depressing auto sales of every kind and making comparably expensive EVs seem out of reach.

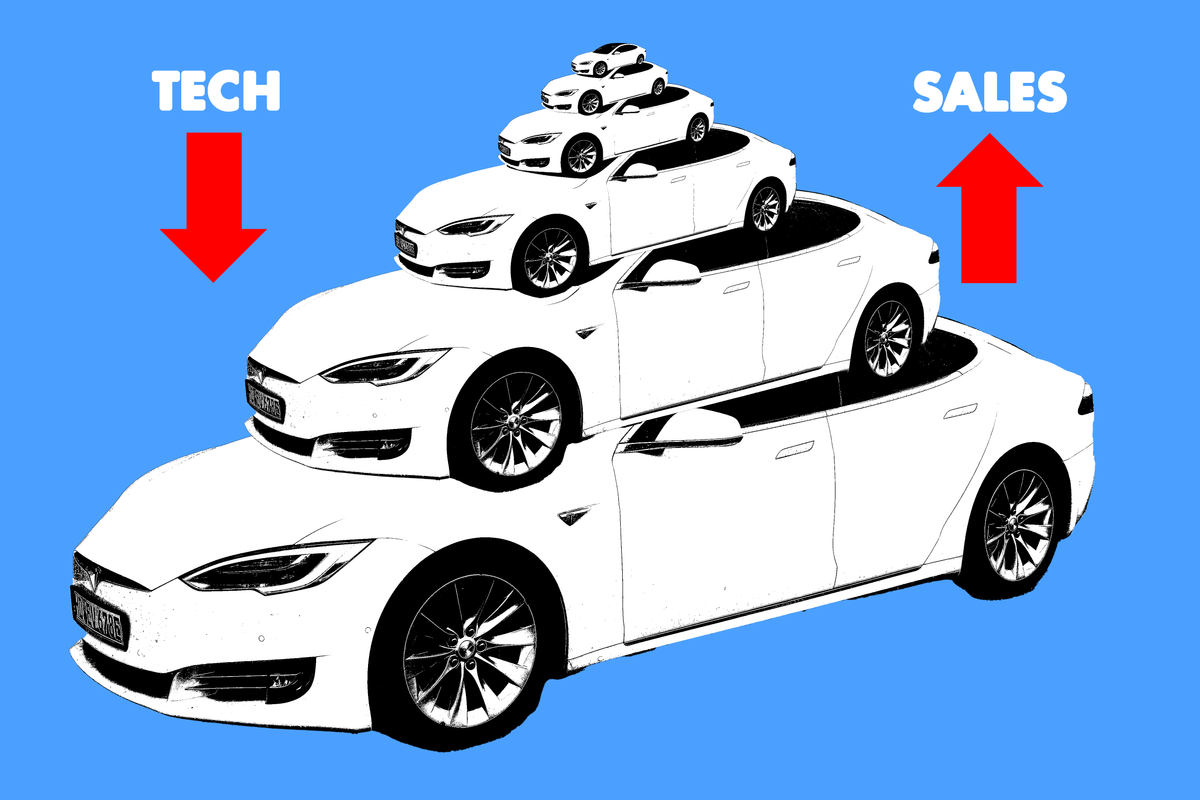

Electrics are expensive because of the costs to make their enormous batteries, the need to retool assembly lines to build a whole new kind of car, and other reasons mostly related to manufacturing. But on top of all that, they’re expensive because of how they’re positioned as a product. To get people excited about electric cars and see them not just as wimpy golf carts, carmakers led by Tesla sold the EV as the tech-forward ride of tomorrow. The look of EVs became all touchscreens and LEDs, smartphone features that meant to have us equate “electric” with “future.”

That design approach, combined with an emphasis on the zoominess an electric powertrain can deliver, gave EVs a sheen of luxury, even though the spartan conditions inside a Tesla bear little resemblance to the cushy environs of a Mercedes-Benz. It allowed Tesla — and Rivian and Lucid — to keep their startup companies afloat by selling expensive cars at the outset to maximize revenue. (It didn’t hurt that the high sticker price provided some room to hide the cost of the battery.)

That worked for the first phase of the EV revolution, when early tech adopters and climate-focused drivers jumped in. But that era is over. As the next era begins, success or failure will rest with the millions of people who make their car decisions on dollars and cents. The declining cost of batteries as companies get better at building them will help the electric vehicle get cheaper. But the other side of the coin is for companies to start selling the EV as just a car — a better one than your dinosaur gasoline-burner, yes, but not some smartphone on wheels sent back from the future.

This isn’t an entirely foreign notion. Cars have long been sold with various “trim levels” that include different packages of features at different price tiers. They’re usually designated by the alphabet soup you see at the end of a vehicle name, like Toyota Corolla XSE or Ford F-150 STX. In the case of the F-150, the extra technology and performance packages can double the starting price of $37,000.

You might think this is an annoying way to buy a car. The system hooks buyers with the promise of a low starting price, only for many to realize the car they actually want is $15,000 more. At the very least, though, it gives you the option to buy the cheap car if you can live without the fancier wheels, heated seats, and advanced suspension.

Gasoline cars could stand to do better in this regard, but it’s especially important for electric vehicles. Today’s market abounds with crossover EVs that pass themselves off as luxurious to get away with a price that bloats into the low $40,000s. Even with a few vehicles coming in the $30,000s, like the basic trim level of the Chevy Equinox EV and the promised revival of the Chevy Bolt, the useful-but-simple EV is a rare thing.

An EV is still an EV if it’s unremarkable. It’s just as good for reducing greenhouse emissions if it looks like my old Ford Escort on the inside: plain cloth seats, chunky physical buttons, and an analog speedometer on the dash. In many ways, it’d be better.

Perhaps this is the pathway to what Tesla, Ford, and others envision when they promise us the $25,000 EV. You’ll probably give up a little in terms of battery size and range, and lose some of the amenities and creature comforts. But what you get, finally, is a truly affordable EV. As someone who grew up on dead-simple transportation, I’d welcome it.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

The transition to clean energy will be expensive today, even if it’ll be cheaper in the long run.

Democrats have embraced a new theory of how to win: run on affordability and cost-of-living concerns while hammering Donald Trump for failing to bring down inflation.

There’s only one problem: their own climate policies.

In state after state, governors and lawmakers are considering pulling back from their climate commitments — or have already reneged on them outright — out of a concern for the high costs that they could soon impose on voters. Democrats have justified the retreat by citing a new regime of sharper inflation, reduced federal support, and a need to deliver cheap energy of all kinds.

“We need to govern in reality,” New York Governor Kathy Hochul, for instance, said in a recent statement defending her approval of new natural gas infrastructure. “We are facing war against clean energy from Washington Republicans.”

Leaders in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and California have all sounded similar notes while making or considering changes to their own states’ policies.

“The trend toward a different approach to energy policy that puts costs and pragmatism first is very real,” Josh Freed, the senior vice president for climate and energy programs at Third Way, a center-left think tank, told me.

“Affordability is the entry ticket for any other policy goal that politicians have,” he continued. “It particularly makes sense on climate and clean energy because we’ve all been talking for years about the need to electrify. If electricity is expensive, then electrification is simply not going to happen.”

The challenge is an old one for climate policy. Climate change — fueled by fossil fuel pollution — will ultimately raise costs through heat waves, extreme weather impacts, and a depleted natural world. But voters don’t go to the polls for lower costs in 2075. They want a cheaper cost of living now.

Democrats have more tools in this fight than ever before, with wind, solar, and batteries often much cheaper than other forms of generation. But to fully realize those cost savings — and to decarbonize the grid faster than utilities or power markets would otherwise go — politicians must push for politically or financially costly policies that speed up the transition, sometimes putting long-term climate goals ahead of near-term affordability concerns.

“We’ve been talking about affordability as the entry point and not the end of the story. It’s important to meet consumers and voters and elected officials where they are,” Justin Balik, the vice president for state policy at Evergreen Action, a climate-focused think tank and advocacy group, told me.

“We can make the argument — because the data is on our side — that clean energy is still cheaper and is a big part of lowering costs.”

Part of what’s driving this shift among Democrats on climate policy is economics. The Trump administration’s war on clean energy has made it more difficult to build clean energy than some state-level policies once envisioned. Many emissions reduction targets passed during the late 2010s or early 2020s — like New York’s, which requires the state to reduce emissions 40% from 1990 levels by 2030 and 85% by 2050 — assumed much faster clean electricity buildouts than have happened in practice. The president’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act will end wind and solar tax credits next year, driving up project costs in some cases by 40% more than once projected.

The president’s war on wind power, in particular, has hit particularly hard in Northeastern states, where grid managers once counted on thousands of megawatts of new offshore wind farms to supply power in the afternoon and evenings while meeting the states’ climate goals. The Trump administration has succeeded in cancelling virtually all of the Northeast’s offshore wind projects outside New York.

But economics do not explain all of the shifts. Democrats seem to believe the president’s war on clean energy has created a fresh rhetorical opening for them: They can now cast themselves as champions of cheap energy in all forms. Some have even revived the old Obama-era “all of the above” slogan for this new era.

“We have an energy crisis. Electricity prices for homeowners and businesses have gone up over 20% in New Jersey. The only answer is all of the above,” Representative Frank Pallone, the ranking member of the House energy committee, told Politico in September.

Even politicians who once championed climate change have downplayed it in recent speeches. New York Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani, who once described himself as a “proud ecosocialist,” barely mentioned climate change during his general election campaign for mayor.

Hochul’s recent moves illustrate the shift. Over the past year, she has delayed implementing New York’s cap-and-invest law, which seeks to reduce statewide carbon emissions 40% by 2030. She also paused the state’s ban on gas stoves and furnaces in new homes and low-rise buildings, which is due to go into effect next year. (A state court has ordered her to implement the cap-and-invest law by February.)

This month, Hochul approved two new natural gas pipelines as part of a rumored deal with the Trump administration to salvage New York’s wind farms. She defended the decision by appealing to — you guessed it — affordability.

“We have adopted an all-of-the-above approach that includes a continued commitment to renewables and nuclear power to ensure grid reliability and affordability,” she said in a statement.

New York’s neighbors have gone down similar paths. In Pennsylvania, Governor Josh Shapiro struck a budget compromise with Republican lawmakers that will remove the state from the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, or RGGI, a compact of Northeastern states to cap carbon pollution from power plants and invest the resulting revenue.

Shapiro blamed Republicans, who he said have “used RGGI as an excuse to stall substantive conversations about energy,” but said he was focused on — yes, again— “cutting costs.”

“I’m going to be aggressive about pushing for policies that create more jobs in the energy sector, bring more clean energy onto the grid, and reduce the cost of energy for Pennsylvanians,” he said before signing the budget deal.

California has also reworked its own climate policy in response to cost-of-living concerns. Earlier this year, it passed an energy package that re-upped its cap-and-trade program while allowing new oil extraction in south-central Kern County. The legislation was partly driven by a fear that local refineries would shutter — and gas prices could soar — without more crude production.

Massachusetts could soon join the pullback. Earlier this month, the state’s House of Representatives fast-tracked a bill that included a provision nullifying a legal mandate to cut carbon emissions in half by 2030, as compared to 1990 levels.

While the bill preserved the state’s longer-term goal to cut emissions by 80% by 2050, it rendered the 2030 mandate “advisory in nature and unenforceable.”

“The number one goal is to save money and adjust to the reality with clean energy,” Representative Mark Cusack, co-chair of the energy and utilities committee and the bill’s sponsor, told the local Commonwealth Beacon. He said the Trump administration’s “assault” on clean energy made the pullback necessary. “We want to get there, but if we’re going to miss our mandates and it’s not the fault of ours, it’s incumbent on us not to get sued and not have the ratepayers be on the hook,” he said.

Cusack’s bill also included measures to transform the state’s Mass Save program — which helps households and businesses to switch to electrified heating and appliances — by dropping the program’s climate mandate and its ban on buying efficient natural gas appliances.

On Monday, lawmakers removed the mandate provision from the bill but preserved its other reforms. While the bill is no longer fast tracked, they could choose to revisit the legislation as soon as next year.

New Jersey may also revisit its own climate commitments. Governor-elect Mikie Sherrill swept to victory this month in part by promising to freeze state utility rates. She could do that in part by lifting or suspending certain “social benefit charges” now placed on state power bills.

In the long term, though, Sherrill will have to pursue other policies to lower rates. Researchers at Evergreen Action and the National Resources Defense Council have argued that changing the state’s electricity policies could lower carbon emissions while saving ratepayers more than $400 a year by 2030.

Balik described the proposal as a “three-legged stool” of immediate rate relief, medium-term clean energy deployment, and long-term utility business model reform. He also mourned that other states have not used revenue from their climate programs to pay for climate programs.

“There’s a danger of looking at cost concerns a little myopically,” he said. “Cap and invest [in New York] was paused for the stated reason that it’s not helpful with cost, but you could use cap-and-invest revenues to pay for things on the rate base now.”

Current conditions: Severe thunderstorms will bring winds of up to 85 miles per hour to parts of the Texarkana region • A cold front in Southeast Asia is stirring waves up to three meters high along the shores of Vietnam • Parts of Libya are roasting in temperatures as high as 95 degrees Fahrenheit.

David Richardson, the acting head of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, resigned Monday after just six months on the job. Richardson had no experience in managing natural disasters, and Axios reported, he “faced sharp criticism for being unavailable” amid the extreme floods that left 130 dead in Central Texas in July. A month earlier, Richardson raised eyebrows when he held a meeting in which he told staff he was unaware the U.S. had a hurricane season. He was, however, a “loyalist” to Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem, CNN reported.

With hurricane season wrapping up this month, President Donald Trump was preparing to fire Richardson in the lead up to an overhaul of the agency, whose resources for carrying out disaster relief he wants to divvy up among the states. When FEMA staffers criticized the move in an open letter over the summer, the agency suspended 40 employees who signed with their names, as I wrote in the newsletter at the time.

The Environmental Protection Agency proposed stripping federal protections from millions of acres of wetlands and streams. The New York Times cast the stakes of the rollback as “potentially threatening sources of clean drinking water for millions of Americans” while delivering “a victory for a range of business interests that have lobbied to scale back the Clean Water Act of 1972, including farmers, home builders, real estate developers, oil drillers and petrochemical manufacturers.” At an event announcing the rulemaking, EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin recognized that the proposal “is going to be met with a lot of relief from farmers, ranchers, and other landowners and governments.” Under the Clean Water Act, companies and individuals need to obtain permits from the EPA before releasing pollutants into the nation’s waterways, and permits from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers before discharging any dredged or fill material such as sand, silt, or construction debris. Yet just eliminating the federal oversight doesn’t necessarily free developers and farmers of permitting challenges since that jurisdiction simply goes to the state.

Americans are spending greater lengths of time in the dark amid mounting power outages, according to a new survey by the data analytics giant J.D. Power. The report, released last month but highlighted Monday in Utility Dive, cited “increased frequency and severity of extreme weather events” as the cause. The average length of the longest blackout of the year increased in all regions since 2022, from 8.1 hours to 12.8 by the midpoint of 2025. Ratepayers in the South reported the longest outages, averaging 18.2 hours, followed by the West, at 12.4 hours. While the duration of outages is worsening, the number of Americans experiencing them isn’t, J.D. Power’s director of utilities intelligence, Mark Spalinger, told Utility Dive. The percentage of ratepayers experiencing “perfect power” without any interruptions is gradually rising, he said, but disasters like storms and fires “are becoming so much more extreme that it creates these longer outage events that utilities are now having to deal with.”

The problem is particularly bad in the summertime. As Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin explained back in June, “the demands on the grid are growing at the same time the resources powering it are changing. Between broad-based electrification, manufacturing additions, and especially data center construction, electricity load growth is forecast to grow several percent a year through at least the end of the decade. At the same time, aging plants reliant on oil, gas, and coal are being retired (although planned retirements are slowing down), while new resources, largely solar and batteries, are often stuck in long interconnection queues — and, when they do come online, offer unique challenges to grid operators when demand is high.”

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

You win some, you lose some. Earlier this month, solar developer Pine Gate Renewables blamed the Trump administration’s policies in its bankruptcy filing. Now a major solar manufacturer is crediting its expansion plans to the president. Arizona-based First Solar said last week it plans to open a new panel factory in South Carolina. The $330 million factory will create 600 new jobs, E&E News reported, if it comes online in the second half of next year as planned. First Solar said the investment is the result of Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act. “The passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act and the Administration’s trade policies boosted demand for American energy technology, requiring a timely, agile response that allows us to meet the moment,” First Solar CEO Mark Widmar said in a statement. “We expect that this new facility will enable us to serve the U.S. market with technology that is compliant with the Act’s stringent provisions, within timelines that align with our customers’ objectives.”

If you want to review what actually goes into making a solar panel, it’s worth checking out Matthew’s explainer from the Climate 101 series.

French oil and gas giant TotalEnergies said Monday it would make a $6 billion investment into power plants across Europe, expanding what The Wall Street Journal called “a strategy that has set it apart from rivals focused on pumping more fossil fuels.” To start, the company agreed to buy 50% of a portfolio of assets owned by Energeticky a Prumyslovy Holding, the investment fund controlled by the Czech billionaire Daniel Kretinsky. While few question the rising value of power generation amid a surge in electricity demand from the data centers supporting artificial intelligence software, analysts and investors “question whether investment in power generation — particularly renewables — will be as lucrative as oil and gas.” Rivals Shell and BP, for example, recently axed their renewables businesses to double down on fossil fuels.

The world has successfully stored as much carbon dioxide as 81,044,946 gasoline-powered cars would emit in a year. The first-ever audit of all major carbon storage projects in the U.S., China, Brazil, Australia, and the Middle East found over 383 million tons of carbon dioxide stored since 1996. “The central message from our report is that CCS works, demonstrating a proven capability and accelerating momentum for geologic storage of CO2,” Samuel Krevor, a professor of subsurface carbon storage at Imperial College London’s Department of Earth Science and Engineering, said in a press release.

New Jersey Governor-elect Mikie Sherrill made a rate freeze one of her signature campaign promises, but that’s easier said than done.

So how do you freeze electricity rates, exactly? That’s the question soon to be facing New Jersey Governor-elect Mikie Sherrill, who achieved a resounding victory in this November’s gubernatorial election in part due to her promise to declare a state of emergency and stop New Jersey’s high and rising electricity rates from going up any further.

The answer is that it can be done the easy way, or it can be done the hard way.

What will most likely happen, Abraham Silverman, a Johns Hopkins University scholar who previously served as the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities’ general counsel, told me, is that New Jersey’s four major electric utilities will work with the governor to deliver on her promise, finding ways to shave off spending and show some forbearance.

Indeed, “We stand ready to work with the incoming administration to do our part to keep rates as low as possible in the short term and work on longer-term solutions to add supply,” Ralph LaRossa, the chief executive of PSE&G, one of the major utilities in New Jersey, told analysts on an earnings call held the day before the election.

PSE&G’s retail bills rose 36% this past summer, according to the investment bank Jefferies. As for what working with the administration might look like, “We expect management to offer rate concessions,” Jefferies analyst Paul Zimbrado wrote in a note to clients in the days following the election, meaning essentially that the utility would choose to eat some higher costs. PSE&G might also get “creative,” which could mean things like “extensions of asset recoverable lives, regulatory item amortization acceleration, and other approaches to deliver customer bill savings in the near-term,” i.e. deferring or spreading out costs to minimize their immediate impact. “These would be cash flow negative but [PSE&G] has the cushion to absorb it,” Zimbrado wrote.

In return, Silverman told me that the New Jersey utilities “have a wish list of things they want from the administration and from the legislature,” including new nuclear plants, owning generation, and investing in energy storage. “I think that they are probably incented to work with the new administration to come up with that list of items that they think they can accomplish again without sacrificing reliability.”

Well before the election, in a statement issued in August responding to Sherrill’s energy platform, PSE&G hinted toward a path forward in its dealings with the state, noting that it isn’t allowed to build or own power generation and arguing that this deregulatory step “precluded all New Jersey electric companies from developing or offering new sources of power supply to meet rising demand and reduce prices.” Of course, the failure to get new supply online has bedeviled regulators and policymakers throughout the PJM Interconnection, of which New Jersey is a part. If Mikie Sherrill can figure out how to get generation online quickly in New Jersey, she’ll have accomplished something more impressive than a rate freeze.

As for ways to accomplish the governor-elect’s explicit goal of keeping price increases at zero, Silverman suggested that large-scale investments could be paid off on a longer timeline, which would reduce returns for utilities. Other investments could be deferred for at least a few years in order to push out beyond the current “bubble” of high costs due to inflation. That wouldn’t solve the problem forever, though, Silverman told me. It could simply mean “seeing lower costs today, but higher costs in the future,” he said.

New Jersey will also likely have to play a role in deliberations happening in front of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission about interconnecting large loads — i.e. data centers — a major driver of costs throughout PJM and within New Jersey specifically. Rules that force data centers to “pay their own way” for transmission costs associated with getting on the grid could relieve some of the New Jersey price crunch, Silverman told me. “I think that will be a really significant piece.”

Then there’s the hard way — slashing utilities’ regulated rates of return.

In a report prepared for the Natural Resources Defence Council and Evergreen Collective and released after the election, Synapse Economics considered reducing utilities’ regulated return on equity, the income they’re allowed to generate on their investments in the grid, from its current level of 9.6% as one of four major levers to bring down prices. A two percentage point reduction in the return on equity, the group found, would reduce annual bills by $40 in 2026.

Going after the return on equity would be a more difficult, more contentious path than working cooperatively on deferring costs and increasing generation, Silverman told me. If voluntary and cooperative solutions aren’t enough to stop rate increases, however, Sherrill might choose to take it anyway. “You could come in and immediately cut that rate of return, and that would absolutely put downward pressure on rates in the short run. But you establish a very contentious relationship with the utilities,” Silverman told me.

Silverman pointed to Connecticut, where regulators and utilities developed a hostile relationship in recent years, resulting in the state’s Public Utilities Regulatory Authority chair, Marissa Gillett, stepping down last month. Gillett had served on PURA since 2019, and had tried to adopt “performance-based ratemaking,” where utility payouts wouldn’t be solely determined by their investment level, but also by trying to meet public policy goals like energy efficiency and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Connecticut utilities said these rules would make attracting capital to invest in the grid more difficult. Gillett’s tenure was also marred by lawsuits from the state’s utilities over accusations of “bias” against them in the ratemaking process. At the same time, environmental and consumer groups hailed her approach.

While Sherrill and her energy officials may not want to completely overhaul how they approach ratemaking, some conflict with the state’s utilities may be necessary to deliver on her signature campaign promise.

Going directly after the utilities’ regulated return “is kind of like making your kid eat their broccoli,” Silverman said. “You can probably make them eat it. You can have a very contentious evening for the rest of the night.”