You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

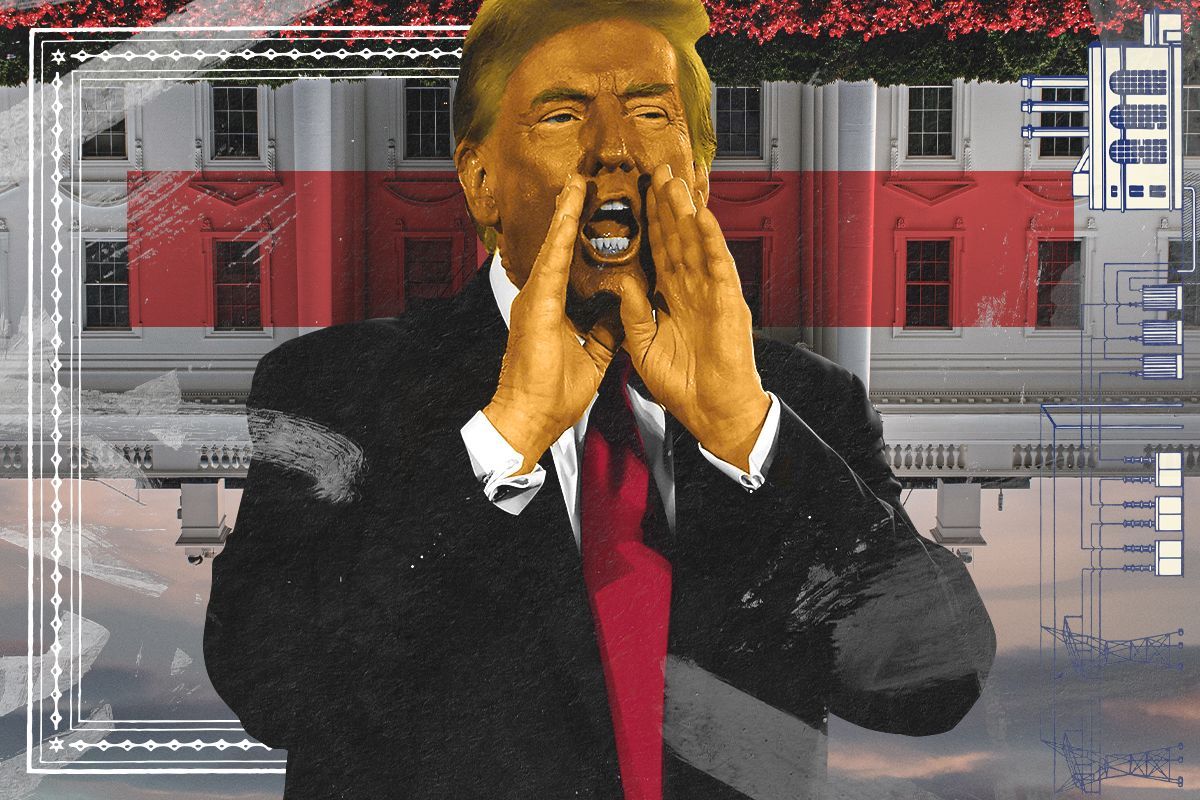

What Trump’s victory means for climate policy.

As of early Wednesday morning, Donald Trump seems likely to be re-elected president of the United States, becoming the first commander in chief since Grover Cleveland to serve non-consecutive terms.

Trump’s probable victory has profound implications for America’s economy, security, and leadership in the world. But it will also impact the country’s energy and environmental policy.

During his first term, Trump made his antipathy for climate policy into a centerpiece of his politics, turning the United States into a global pariah on environmental issues. His second term will play out in a different context — one in which the United States has a real climate law on its books, but also where China has seized a commanding lead in many of the most important zero-carbon technologies. That means Trump’s climate decisions will matter to the country’s economic policy in a way that they never did before.

But what will a Trump administration look like? To begin with: Trump’s victory will put climate advocates — and the broader clean energy economy — on defense for the next four years and beyond.

The first few steps taken by the Trump administration are easy to predict. He will pull the United States out of the Paris Agreement, just like he did during the first term; he will approve a new tranche of liquified natural gas export terminals; and he will block and then begin to roll back the Environmental Protection Agency’s climate rules for power plants, cars, and light-duty trucks.

Not all of these rollbacks will make themselves felt at first. The current set of EPA clean car rules, for instance, apply to vehicles sold through model year 2026. That is close enough to the present that automakers have already begun to make the necessary investments to meet those standards. But vehicles sold in the latter half of this decade will likely face much weaker rules or none at all.

Then the bigger climate policy questions will come. First up is whether Trump tries to repeal or otherwise hinder the Inflation Reduction Act, the landmark climate incentives law passed by President Joe Biden. Trump has said that he wants to “terminate” IRA spending, telling the Economic Club of New York that he seeks to “rescind all unspent funds” under the law.

That would — as Trump hopes — set the country and world back in the fight against climate change. But it would also significantly raise taxes on energy companies (and automakers) while hurting Trump’s own voters. The IRA’s hundreds of billions in investments, which are largely tax credits, have overwhelmingly flowed to Republican districts. According to a Washington Post analysis, districts that backed Trump in 2020 have received three times as much IRA funding as those that supported Biden. New factories making EVs, batteries, and solar panels have popped up across purple and red America, including in Georgia, Arizona, and the Sun Belt. That’s why 18 House Republicans have asked Mike Johnson directly not to repeal the law. If Democrats ultimately win the House of Representatives — we will probably not know for some weeks — then Trump will lack the votes to repeal the law outright.

That’s the theory behind the IRA, at least. The climate law, like the Affordable Care Act before it, is meant to protect itself from repeal by tying itself to local economies across the country. Will that theory hold? Will the climate law survive Trump’s first 100 days? Now we will find out.

Even if the law itself stands, Trump may seek other ways to tamper with it. By saying that he might “rescind the [IRA’s] unspent funds,” he is raising the specter of impoundment, the name for when the president delays or refuses to spend funding that Congress has authorized. Impoundment is of dubious legality, and it is regulated by a 1974 law first passed to rein in Richard Nixon, but Trump might nonetheless try to pause some IRA payments for a time. The first impeachment case against him in 2019 concerned his impoundment of defense funding for Ukraine.

Beyond the IRA, though, there are a number of lurking fissures in a second Trump administration’s climate and environmental policy. Trump has ascended to the White House with the assistance of a strange coalition. It includes Elon Musk, an EV and defense contracting billionaire, and Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., an environmental lawyer turned anti-vaccine crusader and roadkill enthusiast. Trump has promised to put Kennedy in charge of public health policy, and Musk is supposedly going to oversee a new Department of Government Efficiency.

These men agree on some policies. But they do not agree on everything, including in the realm of energy policy. Even during his victory speech, Trump jokingly warned Kennedy to “stay away from the liquid gold,” referencing domestic oil production.

Kennedy is also a lifelong opponent of nuclear energy, and one of his greatest career victories is shutting down New York’s nuclear reactor Indian Point. Musk champions nuclear energy and has said shuttering reactors is “total madness.” The likely next vice president, JD Vance, also tacitly supports nuclear. But Trump, who has officially called for the U.S. to build more nuclear reactors, has sounded more skeptical of nuclear energy lately.

Other fault lines risk dividing this cohort. Kennedy has campaigned against the chemical industry. Will he back the buildout of refineries and chemical plants that Trump has promised? Elon Musk has said that repealing the IRA could benefit Tesla by kneecapping its competitors. Yet much of Tesla’s profit comes from selling regulatory credits created by California and the federal government’s climate policies. If Trump repeals those policies, what will happen to Tesla’s profitability? (Will Musk care?)

The backdrop to these disagreements will be the now forever altered geopolitics for climate policy. Eight years ago, when Trump first took office, climate policy was seen as fundamentally limited to the environment — and clean energy was an important but up-and-coming, almost wholesome niche pursuit that Democrats doted upon. Now the stuff of clean energy — renewables, batteries, and EVs — are central to modern economic development and to geopolitics.

China shows why that is. For every step back that Trump takes on climate policy, China will step forward and take more of a global leadership role. Indeed, partly because of Trump’s own policies, China has taken a commanding lead in zero-carbon technologies over the past decade. In particular it now dominates electric vehicle production, producing cheaper and technologically superior models to anything available elsewhere in the world. If America ends its support for EVs, then China will happily take what global market share remains from U.S. automakers — in fact, it is already doing so. As Trump’s White House steers American climate policy for the rest of the 2020s, they will not just be deciding what direction the U.S. will go in — they will be acting with, or against, the rest of the world.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

On Neil Jacobs’ confirmation hearing, OBBBA costs, and Saudi Aramco

Current conditions: Temperatures are climbing toward 100 degrees Fahrenheit in central and eastern Texas, complicating recovery efforts after the floods • More than 10,000 people have been evacuated in southwestern China due to flooding from the remnants of Typhoon Danas • Mebane, North Carolina, has less than two days of drinking water left after its water treatment plant sustained damage from Tropical Storm Chantal.

Neil Jacobs, President Trump’s nominee to head the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, fielded questions from the Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee on Wednesday about how to prevent future catastrophes like the Texas floods, Politico reports. “If confirmed, I want to ensure that staffing weather service offices is a top priority,” Jacobs said, even as the administration has cut more than 2,000 staff positions this year. Jacobs also told senators that he supports the president’s 2026 budget, which would further cut $2.2 billion from NOAA, including funding for the maintenance of weather models that accurately forecast the Texas storms. During the hearing, Jacobs acknowledged that humans have an “influence” on the climate, and said he’d direct NOAA to embrace “new technologies” and partner with industry “to advance global observing systems.”

Jacobs previously served as the acting NOAA administrator from 2019 through the end of Trump’s first term, and is perhaps best remembered for his role in the “Sharpiegate” press conference, in which he modified a map of Hurricane Dorian’s storm track to match Trump’s mistaken claim that it would hit southern Alabama. The NOAA Science Council subsequently investigated Jacobs and found he had violated the organization’s scientific integrity policy.

The Republican budget reconciliation bill could increase household energy costs by $170 per year by 2035 and $353 per year by 2040, according to a new analysis by Evergreen Action, a climate policy group. “Biden-era provisions, now cut by the GOP spending plan, were making it more affordable for families to install solar panels to lower utility bills,” the report found. The law also cut building energy efficiency credits that had helped Americans reduce their bills by an estimated $1,250 per year. Instead, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act will increase wholesale electricity prices almost 75% by 2035, as well as eliminate 760,000 jobs by the end of the decade. Separately, an analysis by the nonpartisan think tank Center for American Progress found that the OBBBA could increase average electricity costs by $110 per household as soon as next year, and up to $200 annually in some states.

Saudi Arabia’s state-owned oil company Saudi Aramco is in talks with Commonwealth LNG in Louisiana to buy liquified natural gas, Reuters reports. The discussion is reportedly for 2 million tons per year of the facility’s 9.4 million-ton annual export capacity, which would help “cement Aramco’s push into the global LNG market as it accelerates efforts to diversify beyond crude oil exports” and be the “strongest signal yet that Aramco intends to take a material position in the U.S. LNG sector,” OilPrice.com notes. LNG demand is expected to grow 50% globally by 2030, but as my colleague Emily Pontecorvo has reported, President Trump’s tariffs could make it harder for LNG projects still in early development, like Commonwealth, to succeed. “For the moment, U.S. LNG is still interesting,” Anne-Sophie Corbeau, a research scholar focused on natural gas at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy, told Emily. “But if costs increase too much, maybe people will start to wonder.”

Ford confirmed this week that its $3 billion electric vehicle battery plant in Michigan will still qualify for federal tax credits due to eleventh-hour tweaks to the bill’s language, The New York Times reports. Though Ford had said it would build its factory regardless of what happened to the credits, the company’s executive chairman had previously called them “crucial” to the construction of the facility and the employment of the 1,700 people expected to work there. Ford’s battery plant is located in Michigan’s Calhoun County, which Trump won by a margin of 56%. The last-minute tweaks to save the credits to the benefit of Ford “suggest that at least some Republican lawmakers were aware that cuts in the bill would strike their constituents the hardest,” the Times writes.

Italy and Spain are on track to shutter their last remaining mainland coal power plants in the next several months, marking “a major milestone in Europe’s transition to a predominantly renewables-based power system by 2035,” Beyond Fossil Fuels reported Wednesday. To date, 15 European countries now have coal-free grids following Ireland’s move away from coal in 2025.

Italy is set to complete its transition from coal by the end of the summer with the closure of its last two plants, in keeping with the government’s 2017 phase-out target of 2025. Two coal plants in Sardinia will remain operational until 2028 due to complications with an undersea grid connection cable. In Spain, the nation’s largest coal plant will be entirely converted to fossil gas by the end of the year, while two smaller plants are also on track to shut down in the immediate future. Once they do, Spain’s only coal-power plant will be in the Balearic Islands, with an expected phase-out date of 2030.

“Climate change makes this a battle with a ratchet. There are some things you just can’t come back from. The ratchet has clicked, and there is no return. So it is urgent — it is time for us all to wake up and fight.” — Senator Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island in his 300th climate speech on the Senate floor Wednesday night.

Some of the Loan Programs Office’s signature programs are hollowed-out shells.

With a stroke of President Trump’s Sharpie, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act is now law, stripping the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office of much of its lending power. The law rescinds unobligated credit subsidies for a number of the office’s key programs, including portions of the $3.6 billion allocated to the Loan Guarantee Program, $5 billion for the Energy Infrastructure Reinvestment Program, $3 billion for the Advanced Technology Vehicle Manufacturing Program, and $75 million for the Tribal Energy Loan Guarantee Program.

Just three years ago, the Inflation Reduction Act supercharged LPO, originally established in 2005 to help stand up innovative new clean energy technologies that weren’t yet considered bankable for the private sector, expanding its lending authority to roughly $400 billion. While OBBBA leaves much of the office’s theoretical lending authority intact, eliminating credit subsidies means that it no longer really has the tools to make use of those dollars.

Credit subsidies represent the expected cost to the government of providing a loan or a loan guarantee — including the possibility of a default — and thus how much money Congress must set aside to cover these potential losses. So by axing these subsidies, Congress is effectively limiting the amount of lending that the LPO can undertake, given that many third-party lenders would be reluctant to finance riskier, more novel, or larger projects in the absence of federal credit support.

“The LPO is statutorily allowed to take loans on its books to finance these projects in these categories, but it has no credit subsidy by which to take the risk required to do so,” Advait Arun, senior associate of energy finance at the Center for Public Enterprise and a Heatmap contributor, told me.

The particular programs that have been eliminated support new and improved energy technologies, clean energy infrastructure, fuel efficient vehicles, and help native communities access energy project financing. The long-running Loan Guarantee Program and the advanced vehicles program in particular are behind some of the best known LPO efforts, supporting companies such as Tesla, Ford, and NextEra Energy, and projects such as Georgia’s Vogtle nuclear reactors, the Thacker Pass lithium mine, and Shepherd’s Flat, one of the world’s largest wind farms.

The Loan Guarantees Program is “the big Kahuna,” Arun told me. “This is the longest-standing program of the LPO. So to see this defunded is like, you’re decapitating the LPO’s crown jewel.”

The program only has about $11 million left over in credit subsidies, consisting of funding that it received prior to the IRA’s appropriations. That won’t be enough to make any meaningful loans, Arun said, and is more likely to be used to “keep a skeleton crew online” for any remaining administrative tasks.

Then there’s the Energy Infrastructure Reinvestment Program, which the IRA stood up with a whopping $250 billion in lending authority to transition and transform existing fossil fuel infrastructure for clean energy purposes. Now, OBBBA has axed the program’s remaining $5 billion in credit subsidies and replaced it with $1 billion in new subsidies for projects that “retool, repower, repurpose, or replace” existing energy infrastructure, with a focus on expanding capacity and output as opposed to decarbonizing the economy. It also refashioned the program as the predictably-named “Energy Dominance Financing” initiative.

The new-old program — which the law extended through 2028 — no longer requires LPO-funded infrastructure to reduce or sequester emissions, broadening the office’s lending authority to include support for fossil fuel and critical minerals projects. It also adds language encouraging the LPO to “support or enable the provision of known or forecastable electric supply,” which Arun fears is a “backend way of penalizing the addition of renewable energy” on previously developed land.

“Under the Trump administration’s direction, [the LPO] can use that term, ‘known and forecastable,’ to actually just say, well, guess what? Renewables are not known or forecastable because they are intermittent due to the weather,” Arun told me. So while government and private industry were once excited about, say, turning sites originally developed for coal mining or coal ash disposal into solar and battery facilities, those days are probably over.

Carbon capture in particular stands to suffer from this reprogramming, Arun said, explaining that while the Biden LPO saw potential in adding carbon capture to natural gas and coal plants, its current incarnation will no longer allocate funding in any meaningful amount “because reducing emissions is no longer part of the LPO’s mandate.” Some policymakers and clean energy developers had also hoped that excess renewable energy would make it economically feasible to power the production of hydrogen fuel with renewable energy. But with this law — and really each passing day under Trump — a mass buildout of solar and wind seems less and less likely, making it doubtful that green hydrogen will move down the cost curve.

As bleak as this looks, it’s better than it could have been. There was no guarantee that Trump would keep the LPO around at all. Even in this denuded state, the office can still fund the expansion of existing nuclear projects, and perhaps even the buildout of transmission lines or battery projects on brownfield sites, Arun said, depending on how LPO’s leadership ends up interpreting what it means to “increase the capacity output of operating infrastructure.”

But in many ways, what happened with the LPO looks like another instance of the Trump administration picking winners and losers: Yes to clean, firm energy and fossil fuels, no to solar, wind, and electric vehicles.

Take the Advanced Technology Vehicle Manufacturing Program, for example. OBBBA nixed both its credit subsidies and its tens of billions of dollars in lending authority. That’s hardly a surprise, given that the Bush administration created the program in 2007 explicitly to support the domestic development and manufacture of fuel-efficient vehicles and components. But it means that unlike the LPO programs for which lending authority still stands, even if Congress wanted to, it could not redesign the advanced vehicles program to serve a more Trump-aligned purpose. Safer, I suppose, to cut off any opening for funding EVs and hybrids.

The latest LPO rescissions add to the growing list of reasons the private sector has to be wary of the consistently inconsistent landscape for federal funding, Arun told me. He worries that slashing the LPO’s authority at the same time as there’s so much uncertainty around tax credit eligibility will lead some companies to forgo federal funding opportunities altogether.

“We’ll see if private developers even want to play around with the LPO,” Arun told me, “given the uncertainty around the rest of the federal landscape here.”

Electric vehicle batteries are more efficient at lower speeds — which, with electricity prices rising, could make us finally slow down.

The contours of a 30-year-old TV commercial linger in my head. The spot, whose production value matched that of local access programming, aired on the Armed Forces Network in the 1990s when the Air Force had stationed my father overseas. In the lo-fi video, two identical military green vehicles are given the same amount of fuel and the same course to drive. The truck traveling 10 miles per hour faster takes the lead, then sputters to a stop when it runs out of gas. The slower one eventually zips by, a mechanical tortoise triumphant over the hare. The message was clear: slow down and save energy.

That a car uses a lot more energy to go fast is nothing new. Anyone who remembers the 55 miles per hour national speed limit of the 1970s and 80s put in place to counter oil shortages knows this logic all too well. But in the time of electric vehicles, when driving too fast slashes a car’s range and burns through increasingly expensive electricity, the speed penalty is front and center again. And maybe that’s not a bad thing.

You certainly can notice the cost of lead-footedness in a gasoline-powered car. It’s simpler today, when lots of vehicles have digital displays that show the miles per gallon you’re getting, than in the old days when you had to do the math yourself. An EV puts the hard efficiency math right in front of you. Battery life is often displayed in terms of estimated miles of range remaining, and those miles evaporate before your eyes if you climb a mountain or accelerate like a drag racer.

This is no academic concern, like trying to boost one’s fuel efficiency through hypermiling techniques such as gentle acceleration, downhill coasting, and killing the AC. In six years of owning a Tesla Model 3, I’ve pushed its range limits trying to reach far-flung national parks and other destinations where fast chargers are scarce. I’ve found myself in numerous situations where I’ve set the cruise control at exactly the speed limit or slightly below to make sure the car would reach the one and only charging depot in the vicinity. For particularly close calls, I’ve puttered white-knuckled with one eye on Tesla’s in-car energy app — and felt my stomach drop when I found myself underperforming its expectations.

Fortunately, slow works. Three years ago I managed a comfortable round-trip from what was then the closest Tesla Supercharger to Crater Lake National Park by driving there down a 55-mile-per-hour two-lane highway; at freeway speed, my little battery probably wouldn’t have made it. Today, my fully charged Model 3 might make it something like 130 to 140 miles at interstate speed, depending on elevation. Go a little slower and it comes close to matching the 200 miles of supposed range.

Fear is the speed-killer, sure. The chance of being stranded with a dead battery is enough for any driver to be scared straight into observing the posted limit. But having all that data at the ready had already started to affect my driving habits even when there was no danger of stranding myself. It’s hard to watch the range drop when you slam the accelerator without thinking of the Interstellar meme about how much this little maneuver is going to cost us. With the price of electricity at the fast charger rising, I’m much more conscious of wasting a few kilowatt-hours by being in a hurry.

The difference is stunningly clear in the kind of controlled range tests that car sites and EV influencers have been conducting. For example, the State of Charge YouTube channel recently drove the Cadillac Escalade IQ, the fully electric version of the status SUV that is officially rated at 465 miles of range. Driven at exactly 70 miles per hour until it ran out of juice, the big EV exceeded that estimate by traveling 481 miles. With the speedometer held at 60 miles per hour, however, the vehicle went 607 miles — more than 100 miles more.

Granted, the Caddy’s comically large 205 kilowatt-hour battery — more than three times as big as the one in my little Tesla — does the lion’s share of the work in allowing it to go so very many miles. A peek into State of Charge’s data, though, makes it clear what 10 miles per hour can do. Dropping from 70 miles per hour to 60 caused the car’s miles per kilowatt-hour figure to rise from 2.1 to 2.6 or 2.7.

That’s not to say EV ownership turns every driver into an energy-obsessed hypermiler. One blessing of the huge batteries that go into Cadillac EVs and Rivians is freeing their drivers from some of the mental burden of range calculations. With driving ranges reaching well above 300 miles, you’re going to make it to the next plug even if you drive like a maniac.

Even so, the increased awareness of the cost of electricity might make some of us reconsider the casual speeding we all do just to take a few minutes off the trip. That’s a good thing for public safety: Big EV batteries make these vehicles heavier than other cars, on average, and thus potentially more dangerous in auto accidents. And slowing down will be especially relevant as electricity prices outpace inflation. Consumer electricity prices are up nearly 5% over last year and are poised to get worse: The budget reconciliation bill signed by President Trump last week won’t help, as one projection sees it leading to an increase in annual energy bills of up to $290 by 2035.

To be honest, the biggest problem of slowing down a little isn’t really the extra time it takes to get someplace. It’s trying to conserve in a world where 5 to 10 miles per hour over the speed limit is the expectation. I once had to cross 140 miles of wind-swept New Mexico expanse from Albuquerque to Gallup on a single charge, a task that required driving 55 miles per hour in a 65 zone of the interstate, holding on tight as semi trucks flew past me in revved aggravation. We made it. But if you really want to make your electrons go farther, then be prepared to become the target of road rage by the hasty and the aggrieved.