You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

The Rivian R1S’s sprawling touchscreen delivered the good news: After 40-plus minutes of charging at the halfway-point pit stop between San Francisco and L.A., we could easily make it the 220 miles home. Sure, fate might dictate an extra pit stop if the toddler collapsed into an inconsolable meltdown or one of the adults needed a bathroom break. But the math was clear: At a 95% charge, the big electric SUV’s battery could go an estimated 350 miles in Conserve Mode — more than enough to get home from Coalinga in one shot.

And then it happened. The baby held it together, thanks in part to the soothing power of pop song covers by a singing cat. We blew through the last leg of the journey over the mountains into greater Los Angeles.

For a fossil fuel vehicle, this would have been no big achievement; just about any old gas-burner could make a 400-mile highway trip with a single stop. In an EV, it’s a picture of what’s becoming possible as batteries get bigger and better, and more EVs have ranges that top 300 miles. Because believe me, if you want to road trip in an electric vehicle, you should buy all the range you can afford.

When my wife and I got a Tesla Model 3 six years ago, our simple single-motor edition came with a nominal 240 miles of Environmental Protection Agency-rated range. Pretty good, we thought. That’s nearly the distance to Las Vegas, and certainly enough to make the trip of 350 miles or so to San Francisco on one recharging stop.

How young I was. Range, remember, is a relative thing; an EPA miles rating doesn’t mean you’ll go that far. Compared to driving 50 miles per hour on some lonesome highway, range dips noticeably when you’re ignoring the 70 mile-per-hour speed limit on Interstate 5, just trying to get home. It is also impractical to use a battery’s entire capacity. Once you’ve passed 80% to 85% capacity, recharging slows dramatically, so much so that it’s annoying to sit there and accumulate a few extra miles unless you really need them. And when you’re driving, the miles below 10% aren’t usable unless you’re totally comfortable arriving at the next charger with just a percent or two left on the battery.

Because of these limitations, my little Tesla can’t really travel more than 140 to 150 real miles at freeway speed. As the battery has gotten older and its range has dwindled, the journey to San Francisco can be accomplished in two charging stops only if we begin with a full battery, carefully plan our stops, and don’t have to waste energy running the A/C on full blast because it’s obscenely hot. More commonly, the trip takes three full charging stops.

To be clear, this is not the worst thing in the world. It adds travel time, certainly, when compared to the Cannonball Run my wife used to make in college, stopping just once at the halfway point to get some gas. But with a baby in the back, we’re taking at least a couple breaks no matter what. The real problem driving long distances in an EV with low or fading range is that the trip becomes an exercise in logistics. You’re constantly aware of the car’s estimate for how much range will remain when you reach your destination — and alarmed if that number starts to decline. You also rarely stop just because you want to when there are so many stops you have to make.

To get a taste of the better life to come, I borrowed an R1S Tri Max Ascend for a long weekend trip to the Bay Area. A triple-motor, absurdly overpowered version of Rivian’s SUV, the Tri Max is a $105,000, nearly 7,000-pound behemoth that can outrace sports cars on a drag strip. Yet because of its enormous battery pack, the giant EV can still deliver more than 300 real-world miles on a charge, enough to fulfill my long-held fantasy of charging only once on the way to San Francisco.

The difference was apparent within the first two hours. As we crept through heavy traffic leaving Los Angeles on U.S. 101, the baby threw a fit. In my shorter-range EV, I would’ve powered through the ear-piercing misery for as long as it took to reach a Supercharger in Santa Barbara, then eaten whatever happened to be around. In the R1S, we knew we could make it comfortably all the way to Rivian’s fast charger in Pismo Beach, about halfway to S.F. So we pulled off in one of our favorite seaside towns, Carpinteria, for happy hour crab cakes to give the child a break from her seat.

It took a lengthy stop in Pismo to refill the Rivian’s gigantic battery, one we spent buying baby clothes at the outlet mall. But that got us to the Bay Area, where a quick pit stop at one of the Tesla Superchargers now open to non-Tesla cars provided plenty of electricity to bum around town all weekend. The only hitch in road-tripping in the Rivian is where you choose to stay — our hotel had one compatible slow-charging bay for overnight energy, but I never could snag it.

No, long range can’t duplicate the mad dash experience for the kind of drivers who want to stop only five minutes every four hours in order to “make good time.” And EV driving still requires more mental math than the old ways, where you would notice the fuel gauge is getting close to E and pull off at any of America’s multitude of gas stations. But extended range does give the EV driver more of the classic road trip experience, where stops are determined by life — bathroom breaks, coffee refills, backseat tantrums — and not solely by charging needs. And there’s nothing like having enough range to just get home when everybody in the family needs the trip to end.

The good news is that range is getting better across the board. A half-decade ago, a lot of pure EVs came with ranges that were barely above 200. Now, many more come with at least 240 to 250 miles in their entry-level versions, with battery upgrades available that take the figure north of 300.

The bad news is that range costs. No, you don’t have to splurge for a six-figure vehicle like the R1S Tri Max to get a big battery. Even with more affordable EVs, though, it costs thousands of dollars extra to get the larger battery, and with it, road trip peace of mind. An ideal solution to this problem is leasing, which gets people into better EVs for a lower monthly payment (and doesn’t leave them worrying about a battery’s long-term health as they would if they bought the car). But a lot of great lease deals are going to get a bit worse if the current government succeeds in undoing electric vehicle incentives.

For plenty of drivers, the extra cost won’t be practical or worthwhile — they could spend much less to stick with a hybrid vehicle, or settle for making a few extra road trip stops in a less expensive EV. But if I’m being honest, long range is a life-changer for anybody who loves the open road. EVs are already better than combustion cars in the city. Once driving range reaches well above 300 miles, they’re just about as good on the interstate, too.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

The startup — founded by the former head of Tesla Energy — is trying to solve a fundamental coordination problem on the grid.

The concept of virtual power plants has been kicking around for decades. Coordinating a network of distributed energy resources — think solar panels, batteries, and smart appliances — to operate like a single power plant upends our notion of what grid-scale electricity generation can look like, not to mention the role individual consumers can play. But the idea only began taking slow, stuttering steps from theory to practice once homeowners started pairing rooftop solar with home batteries in the past decade.

Now, enthusiasm is accelerating as extreme weather, electricity load growth, and increased renewables penetration are straining the grid and interconnection queue. And the money is starting to pour in. Today, home battery manufacturer and VPP software company Lunar Energy announced $232 million in new funding — a $102 million Series D round, plus a previously unannounced $130 million Series C — to help deploy its integrated hardware and software systems across the U.S.

The company’s CEO, Kunal Girotra, founded Lunar Energy in the summer of 2020 after leaving his job as head of Tesla Energy, which makes the Tesla Powerwall battery for homeowners and the Megapack for grid-scale storage. As he put it, back then, “everybody was focused on either building the next best electric car or solving problems for the grid at a centralized level.” But he was more interested in what was happening with households as home battery costs were declining. “The vision was, how can we get every home a battery system and with smart software, optimize that for dual benefit for the consumer as well as the grid?”

VPPs work by linking together lots of small energy resources. Most commonly, this includes solar, home batteries, and appliances that can be programmed to adjust their energy usage based on grid conditions. These disparate resources work in concert conducted by software that coordinates when they should charge, discharge, or ramp down their electricity use based on grid needs and electricity prices. So if a network of home batteries all dispatched energy to the grid at once, that would have the same effect as firing up a fossil fuel power plant — just much cleaner.

Lunar’s artificial intelligence-enabled home energy system analyzes customers’ energy use patterns alongside grid and weather conditions. That allows Lunar’s battery to automatically charge and discharge at the most cost-effective times while retaining an adequate supply of backup power. The batteries, which started shipping in California last year, also come integrated with the company’s Gridshare software. Used by energy companies and utilities, Gridshare already manages all of Sunrun’s VPPs, including nearly 130,000 home batteries — most from non-Lunar manufacturers — that can dispatch energy when the grid needs it most.

This accords with Lunar’s broader philosophy, Girotra explained — that its batteries should be interoperable with all grid software, and its Gridshare platform interoperable with all batteries, whether they’re made by Lunar or not. “That’s another differentiator from Tesla or Enphase, who are creating these walled gardens,” he told me. “We believe an Android-like software strategy is necessary for the grid to really prosper.” That should make it easier for utilities to support VPPs in an environment where there are more and more differentiated home batteries and software systems out there.

And yet the real-world impact of VPPs remains limited today. That’s partially due to the main problem Lunar is trying to solve — the technical complexity of coordinating thousands of household-level systems. But there are also regulatory barriers and entrenched utility business models to contend with, since the grid simply wasn’t set up for households to be energy providers as well as consumers.

Girotra is well-versed in the difficulties of this space. When he first started at Tesla a decade ago, he helped kick off what’s widely considered to be the country’s first VPP with Green Mountain Power in Vermont. The forward-looking utility was keen to provide customers with utility-owned Tesla Powerwalls, networking them together to lower peak system demand. But larger VPPs that utilize customer-owned assets and seek to sell energy from residential batteries into wholesale electricity markets — as Lunar wants to do — are a different beast entirely.

Girotra thinks their time has come. “This year and the next five years are going to be big for VPPs,” he told me. The tide started to turn in California last summer, he said, after a successful test of the state’s VPP capacity had over 100,000 residential batteries dispatching more than 500 megawatts of power to the grid for two hours — enough to power about half of San Francisco. This led to a significant reduction in electricity demand during the state’s evening peak, with the VPP behaving just like a traditional power plant.

Armed with this demonstration of potential and its recent influx of cash, Lunar aims to scale its battery fleet, growing from about 2,000 deployed systems today to about 10,000 by year’s end, and “at least doubling” every year after that. Ultimately, the company aims to leverage the popularity of its Gridshare platform to become a market maker, helping to shape the structure of VPP programs — as it’s already doing with the Community Choice Aggregators that it’s partnered with so far in California.

In the meantime, Girotra said Lunar is also involved in lobbying efforts to push state governments and utilities to make it easier for VPPs to participate in the market. “VPPs were always like nuclear fusion, always for the future,” he told me. But especially after last year’s demonstration, he thinks the entire grid ecosystem, from system operators to regulators, are starting to realize that the technology is here today. ”This is not small potatoes anymore.”

If all the snow and ice over the past week has you fed up, you might consider moving to San Francisco, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Austin, or Atlanta. These five cities receive little to no measurable snow in a given year; subtropical Atlanta technically gets the most — maybe a couple of inches per winter, though often none. Even this weekend’s bomb cyclone, which dumped 7 inches across parts of northeastern Georgia, left the Atlanta suburbs with too little accumulation even to make a snowman.

San Francisco and the aforementioned Sun Belt cities are also the five pilot locations of the all-electric autonomous-vehicle company Waymo. That’s no coincidence. “There is no commercial [automated driving] service operating in winter conditions or freezing rain,” Steven Waslander, a University of Toronto robotics professor who leads WinTOR, a research program aimed at extending the seasonality of self-driving cars, told me. “We don’t have it completely solved.”

Snow and freezing rain, in particular, are among the most hazardous driving conditions, and 70% of the U.S. population lives in areas that experience such conditions in winter. But for the same reasons snow and ice are difficult for human drivers — reduced visibility, poor traction, and a greater need to react quickly and instinctively in anticipation of something like black ice or a fishtailing vehicle in an adjacent lane — they’re difficult for machines to manage, too.

The technology that enables self-driving cars to “see” the road and anticipate hazards ahead comes in three varieties. Tesla Autopilot uses cameras, which Tesla CEO Elon Musk has lauded for operating naturally, like a human driver’s eye — but they have the same limitations as a human eye when conditions deteriorate, too.

Lidar, used by Waymo and, soon, Rivian, deploys pulses of light that bounce off objects and return to sensors to create 3D images of the surrounding environment. Lidar struggles in snowy conditions because the sensors also absorb airborne particles, including moisture and flakes. (Not to mention, lidar is up to 32 times more expensive than Tesla’s comparatively simple, inexpensive cameras.) Radar, the third option, isn’t affected by darkness, snow, fog, or rain, using long radio wavelengths that essentially bend around water droplets in the air. But it also has the worst resolution of the bunch — it’s good at detecting cars, but not smaller objects, such as blown tire debris — and typically needs to be used alongside another sensor, like lidar, as it is on Waymo cars.

Driving in the snow is still “definitely out of the domain of the current robotaxis from Waymo or Baidu, and the long-haul trucks are not testing those conditions yet at all,” Waslander said. “But our research has shown that a lot of the winter conditions are reasonably manageable.”

To boot, Waymo is now testing its vehicles in Tokyo and London, with Denver, Colorado, set to become the first true “winter city” for the company. Waymo also has ambitions to expand into New York City, which received nearly 12 inches of snow last week during Winter Storm Fern.

But while scientists are still divided on whether climate change is increasing instances of polar vortices — which push extremely cold Arctic air down into the warmer, moister air over the U.S., resulting in heavy snowfall — we do know that as the planet warms, places that used to freeze solid all winter will go through freeze-thaw-refreeze cycles that make driving more dangerous. Freezing rain, which requires both warm and cold air to form, could also increase in frequency. Variability also means that autonomous vehicles will need to navigate these conditions even in presumed-mild climates such as Georgia.

Snow and ice throw a couple of wrenches at autonomous vehicles. Cars need to be taught how to brake or slow down on slush, soft snow, packed snow, melting snow, ice — every variation of winter road condition. Other drivers and pedestrians also behave differently in snow than in clear weather, which machine learning models must incorporate. The car itself will also behave differently, with traction changing at critical moments, such as when approaching an intersection or crosswalk.

Expanding the datasets (or “experience”) of autonomous vehicles will help solve the problem on the technological side. But reduced sensor accuracy remains a big concern — because you can only react to hazards you can identify in the first place. A crust of ice over a camera or lidar sensor can prevent the equipment from working properly, which is a scary thought when no one’s in the driver’s seat.

As Waslander alluded to, there are a few obvious coping mechanisms for robotaxi and autonomous vehicle makers: You can defrost, thaw, wipe, or apply a coating to a sensor to keep it clear. Or you can choose something altogether different.

Recently, a fourth kind of sensor has entered the market. At CES in January, the company Teradar demonstrated its Summit sensor, which operates in the terahertz band of the electromagnetic spectrum, a “Goldilocks” zone between the visible light used by cameras and the human eye and radar. “We have all the advantages of radar combined with all the advantages of lidar or camera,” Gunnar Juergens, the SVP of product at Teradar, told me. “It means we get into very high resolution, and we have a very high robustness against any weather influence.”

The company, which raised $150 million in a Series B funding round last year, says it is in talks with top U.S. and European automakers, with the goal of making it onto a 2028 model vehicle; Juergens also told me the company imagines possible applications in the defense, agriculture, and health-care spaces. Waslander hadn’t heard of Teradar before I told him about it, but called the technology a “super neat idea” that could prove to be a “really useful sensor” if it is indeed able to capture the advantages of both radar and lidar. “You could imagine replacing both with one unit,” he said.

Still, radar and lidar are well-established technologies with decades of development behind them, and “there’s a reason” automakers rely on them, Waslander told me. Using the terahertz band, “there’s got to be some trade-offs,” he speculated, such as lower measurement accuracy or higher absorption rates. In other words, while Teradar boasts the upsides of both radar and lidar, it may come with some of their downsides, too.

Another point in Teradar’s favor is that it doesn’t use a lens at all — there’s nothing to fog, freeze, or salt over. The sensor could help address a fundamental assumption of autonomy — as Juergen put it, “if you transfer responsibility from the human to a machine, it must be better than a human.” There are “very good solutions on the road,” he went on. “The question is, can they handle every weather or every use case? And the answer is no, they cannot.” Until sensors can demonstrate matching or exceeding human performance in snowy conditions — whether through a combination of lidar, cameras, and radar, or through a new technology such as Teradar’s Summit sensor — this will remain true.

If driving in winter weather can eventually be automated at scale, it could theoretically save thousands of lives. Until then, you might still consider using that empty parking lot nearby to brush up on your brake pumping.

Otherwise, there’s always Phoenix; I’ve heard it’s pleasant this time of year.

Current conditions: After a brief reprieve of temperatures hovering around freezing, the Northeast is bracing for a return to Arctic air and potential snow squalls at the end of the week • Cyclone Fytia’s death toll more than doubled to seven people in Madagascar as flooding continues • Temperatures in Mongolia are plunging below 0 degrees Fahrenheit for the rest of the workweek.

Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum suggested the Supreme Court could step in to overturn the Trump administration’s unbroken string of losses in all five cases where offshore wind developers challenged its attempts to halt construction on turbines. “I believe President Trump wants to kill the wind industry in America,” Fox Business News host Stuart Varney asked during Burgum’s appearance on Tuesday morning. “How are you going to do that when the courts are blocking it?” Burgum dismissed the rulings by what he called “court judges” who “were all at the district level,” and said “there’s always the possibility to keep moving that up through the chain.” Burgum — who, as my colleague Robinson Meyer noted last month, has been thrust into an ideological crisis over Trump’s actions toward Greenland — went on to reiterate the claims made in a Department of Defense report in December that sought to justify the halt to all construction on offshore turbines on the grounds that their operation could “create radar interference that could represent a tremendous threat off our highly populated northeast coast.” The issue isn’t new. The Obama administration put together a task force in 2011 to examine the problem of “radar clutter” from wind turbines. The Department of Energy found that there were ways to mitigate the issue, and promoted the development of next-generation radar that could see past turbines.

The Trump administration, meanwhile, is facing accusations of violating the Constitution with its orders to keep coal-fired power stations operating past planned retirement. By mandating their coal plants stay open, two electrical cooperatives in Colorado said the Energy Department’s directive “constitutes both a physical taking and a regulatory taking” of property by the government without just compensation or due process, Utility Dive reported.

Back in December, the promise of a bipartisan deal on permitting reform seemed possible as the SPEED Act came up for a vote in the House. At the last minute, however, far-right Republicans and opponents of offshore wind leveraged their votes to win an amendment specifically allowing President Donald Trump to continue his attempts to kill off the projects to build turbines off the Eastern Seaboard. With key Democrats in the Senate telling Heatmap’s Jael Holzman that their support hinged on legislation that did the opposite of that, the SPEED Act stalled out. Now a new bipartisan bill aims to rectify what went wrong. The FREEDOM Act — an acronym for “Fighting for Reliable Energy and Ending Doubt for Open Markets” — would prevent a Republican administration from yanking permits from offshore wind or a Democratic one from going after already-licensed oil and gas projects, while setting new deadlines for agencies to speed up application reviews. I got an advanced copy of the bill Monday night, so you can read the full piece on it here on Heatmap.

One element I didn’t touch on in my story is what the legislation would do for geothermal. Next-generation geothermal giant Fervo Energy pulled off its breakthrough in using fracking technology to harness the Earth’s heat in more places than ever before just after the Biden administration completed work on its landmark clean energy bills. As a result, geothermal lost out on key policy boosts that, for example, the next-generation nuclear industry received. The FREEDOM Act would require the government to hold twice as many lease sales on federal lands for geothermal projects. It would also extend the regulatory shortcuts the oil and gas industry enjoys to geothermal companies.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

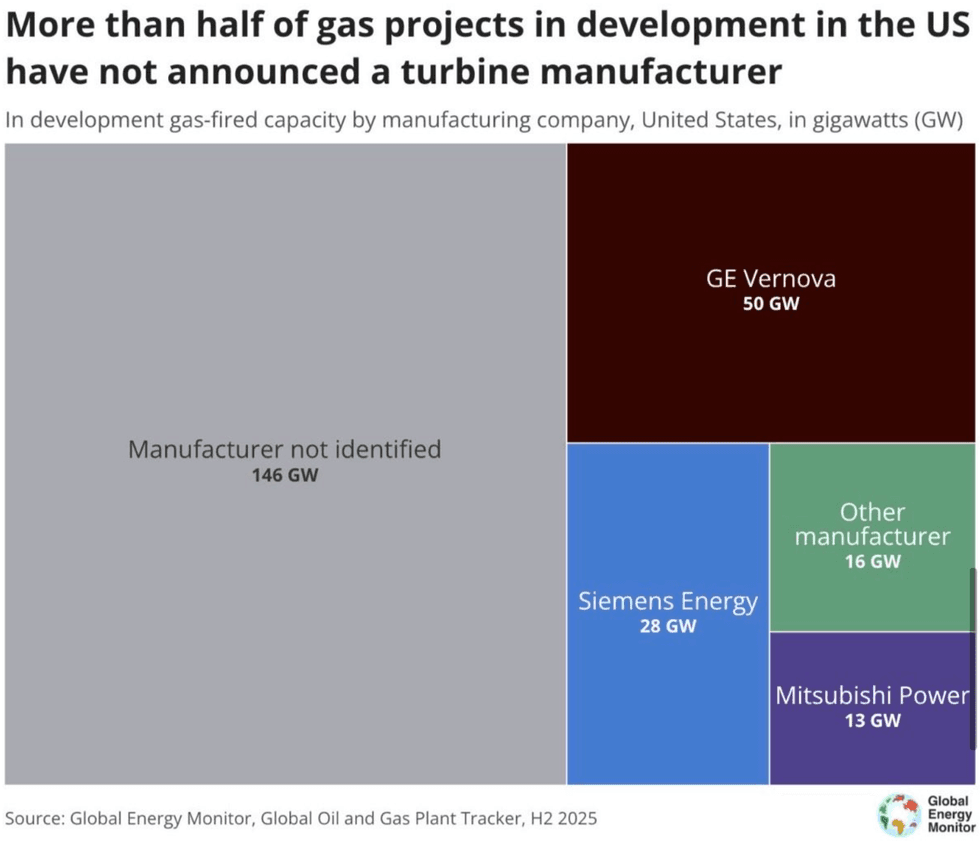

Take a look at the above chart. In the United States, new gas power plants are surging to meet soaring electricity demand. At last count, two thirds of projects currently underway haven’t publicly identified which manufacturer is making their gas turbines. With the backlog for turbines now stretching to the end of the decade, Siemens Energy wants to grow its share of booming demand. The German company, which already boasts the second-largest order book in the U.S. market, is investing $1 billion to produce more turbines and grid equipment. “The models need to be trained,” Christian Bruch, the chief executive of Siemens Energy, told The New York Times. “The electricity need is going to be there.”

While most of the spending is set to go through existing plants in Florida and North Carolina, Siemens Energy plans to build a new factory in Mississippi to produce electric switchgear, the equipment that manages power flows on the grid. It’s hardly alone. In September, Mitsubishi announced plans to double its manufacturing capacity for gas turbines over the next two years. After the announcement, the Japanese company’s share price surged. Until then, investors’ willingness to fund manufacturing expansions seemed limited. As Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin put it, “Wall Street has been happy to see developers get in line for whatever turbines can be made from the industry’s existing facilities. But what happens when the pressure to build doesn’t come from customers but from competitors?” Siemens just gave its answer.

At his annual budget address in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro touted Amazon’s plans to invest $20 billion into building two data center campuses in his state. But he said it’s time for the state to become “selective about the projects that get built here.” To narrow the criteria, he said developers “must bring their own power generation online or fully fund new generation to meet their needs — without driving up costs for homeowners or businesses.” He insisted that data centers conserve more water. “I know Pennsylvanians have real concerns about these data centers and the impact they could have on our communities, our utility bills, and our environment,” he said, according to WHYY. “And so do I.” The Democrat, who is running for reelection, also called on utilities to find ways to slash electricity rates by 20%.

For the first time, every vehicle on Consumer Reports’ list of top picks for the year is a hybrid (or available as one) or an electric vehicle. The magazine cautioned that its endorsement extended to every version of the winning vehicles in each category. “For example, our pick of the Honda Civic means we think the gas-only Civic, the hybrid, and the sporty Si are all excellent. But for some models, we emphasize the version that we think will work best for most people.” But the publication said “the hybrid option is often quieter and more refined at speed, and its improved fuel efficiency usually saves you money in the long term.”

Elon Musk wants to put data centers in space. In an application to the Federal Communications Commission, SpaceX laid out plans to launch a constellation of a million solar-powered data centers to ease the strain the artificial intelligence boom is placing on the Earth’s grids. Each data center, according to E&E News, would be 31 miles long and operate more than 310 miles above the planet’s surface. “By harnessing the Sun’s abundant, clean energy in orbit — cutting emissions, minimizing land disruption, and reducing the overall environmental costs of grid expansion — SpaceX’s proposed system will enable sustainable AI advancement,” the company said in the filing.