You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

An interview with the long-shot candidate with a moonshot climate proposal

In a different world, maybe, Marianne Williamson is president.

There has been no such luck in this one — the 2020 campaign of the best-selling self-help author ended before the Iowa Democratic caucuses, her poll numbers never cresting the low single digits nationally. Though she managed to raise more money than either Washington Governor Jay Inslee or New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio during that time, most Americans likely best remember Williamson today for the memes and jokes about crystals, or the moment during one of the early, carnivalesque Democratic debates when she memorably warned Donald Trump that “I am going to harness love for political purposes and sir, love will win.”

Williamson is running again in 2024, a campaign that might seem even more quixotic than the last: After all, a primary challenger has never won a nomination against an incumbent president in modern U.S. history. During my Zoom conversation with her last week, she as much as admitted that we’re probably not living in a reality right now where the country would conceivably “elect me president.” (Williamson is facing other obstacles, too — there are reports of high turnover within her campaign as well as rumors of her alleged temper contributing to a toxic workplace culture, claims she’s pushed back on).

But if her 2020 campaign was often treated as a joke, the 2024 campaign is earning Williamson a cautious reappraisal. For one thing, she’s huge with the TikTok crowd. Though she was only polling around 9% this spring, that’s “higher than most of Donald Trump’s declared challengers in the GOP primary,” Politico noted at the time; Williamson also, by another poll’s findings, held 20% of the under-30 vote.

Some of the 2020 jokes have also started to look somewhat unfair in retrospect; Eric Adams, the mayor of New York City, is into crystals, too, but he hasn’t faced nearly the same gleeful mockery that Williamson has. Jacobin’s Liza Featherstone went as far as to write a piece earlier this year defending Williamson as a “serious” progressive candidate with a platform that is “essentially the Bernie Sanders 2016 and 2020 agenda.”

Much of the renewed attraction is related to Williamson’s climate agenda. When President Biden approved the Willow Project this spring, he alienated some of his young supporters who felt betrayed by his reneging on “no more drilling.” Williamson has been loudly critical of the Willow Project, and her campaign’s climate action statement is nearly 3,000 words long (and makes no less than three references to World War II).

Calling Williamson’s climate plan “ambitious” is an understatement: She promises everything from reaching “100 percent renewable energy” and phasing out fossil fuel vehicles by 2035; to decarbonizing all buildings by 2045; to investing half the federal funds for highways into transit. But as Williamson herself would say, “ambitious” is what we need. We spoke last week about her vision and what it would take to make it work.

Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

I’m in London because my daughter had a baby.

Oh, of course I was. Yes, of course. I don’t know how nature could be any louder at this point. This is no longer about what will happen if we don’t act: This is about what is already happening. It wasn’t just the smoke on the East Coast and Canada, either. It was also all the dead fish in Texas. It’s unspeakable.

But our state of — I don’t know if it’s a state of denial. I think we have a critical mass of people who are no longer in denial. The problem is the sclerotic, paralytic nature of the political system in so many areas; the problem is not with the people.

I think the environmental movement has been successful at getting the word not just out, but in the hearts and minds of enough people. But our political system at this point does more to thwart than to facilitate. That’s why it’s so heartbreaking to see tens of thousands of people out on the street. The people are speaking but the voice of the people is not reflected in our political realities. It’s not expressed in our political policies because, obviously, the financial influence of big oil and other nefarious actors drowns out the voice of the people.

It’s going to take a certain kind of leader. There’s a book called No Ordinary Time about Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt during the Depression and World War II. And when Hitler was beginning his march to Europe, Roosevelt began to realize pretty early — particularly given conditions in England — that we had a serious problem here that would probably only be dealt with if the United States ended the war.

But there was a tremendous trend towards isolationism in that time particularly because of the experience of World War I. So Roosevelt knew that he couldn’t just decide to enter the war. He had to talk to the American people. That’s what the fireside chats were. He had to convince people. And if you have a leader who’s more concerned about following the leader, who’s more concerned about the donors than about, in this case, the survivability of the planet and the species that live on it, then you can’t blame the people for the fact that no one is doing what is necessary to harness the energy we need.

Well, the Inflation Reduction Act had some very nice investments in green energy. [Claps sarcastically]. Applause, applause, applause — until you see that he also approved the Willow Project. If you look at the effects of the Willow Project, that will nullify the effects of the energy investments. (Editors’ Note: The Willow Project is expected to increase annual American emissions by 9.2 million metric tons of carbon dioxide. According to the Rhodium Group, the IRA is projected to cut “439-660 million metric tons in 2030.”)

Plus you add to that the expansion of the military budget and you remember that the U.S. defense establishment, the U.S. military, is the single largest global institutional emitter of greenhouse gases. So this is how that establishment playbook works. Look at what I’m doing! Look at what I’m doing! I’m investing in green energy! I understand that the climate crisis is an existential threat, and I’m giving all this [money to] green energy, nobody’s given so much investment! And then over here, on the other hand, I’m giving more oil drilling permits even than Trump did. I’m approving the Willow Project, I’m expanding the military budget, and I’m approving the exploitation of liquefied natural gas — and we’ve been trained to just say, “oh, okay.”

My problem with nuclear energy is not that I don’t understand the technological advances that make it arguably a safe technology. I understand that. People have said to me so often, “Marianne, you’ve got to read this, Marianne you've got to read that, the technology has improved, it’s safe.” It’s not that I don’t trust the technology. It’s that I don’t trust people.

It’s not about the state of the technology; it’s about the state of our humanity and also the state of our climate. I mean, there’s no predicting weather. There are certain weather catastrophes that could and would override the safety measures of nuclear plants no matter what we did.

And I’m not convinced we need it. When World War II started, we basically had no standing army really. And England didn’t have anything. And Hitler not only had spent the last five years building up his military, but then he absorbed the industrial capacity of every country that he invaded. We had nothing, but you know what? We needed to get something. And we did — and that’s the issue here. The issue is not that we cannot technologically make this happen. The issue is harnessing the energy of the American people in such a way that enough of us want to.

If this country gets to the point where they would elect me president, it’s reasonable to assume it would also be at a place where they were ready to elect the kind of congressional and senatorial legislators who would agree with me and align with me in great enough numbers that my agenda could be effectuated.

[Laughing] Not necessarily.

There are many thousands of people in this country who make a living, pay their rent, put food on the table, and send their kids to college because they work at jobs that are at least indirectly related to the fossil fuel industry. That is not to be ignored. That is not to be underappreciated. There are people who would say, “Wait a minute, I make over $100,000 a year working for an oil company and you want me to make $15 an hour installing solar panels?” That person should not drop through the cracks.

Now, that’s gonna take a lot of mobilization right there when it comes to manufacturing, when it comes to research, when it comes to technology. We can move things laterally but we have to have the intention to do that.

The way I see it, we have a really, really, really big ship here. It’s headed for the iceberg. We’ve got to turn this thing around, but it can’t be turned around in a jackknife; it has to be turned around responsibly and wisely. And part of that, just transition, is respecting the needs of people. And the way we make that transition is very important to me. A lot of those people would not have voted for me, by the way.

I think a lot of people who would be fearful, in the short term, that they would lose out might not vote for me. But that would only be on the misperception that I underestimate their needs.

During the last campaign, I was basically living in Iowa. And I never had been that up close and personal with animals factory farming. And once you have experienced it, seen it, smelled it, you see it in a very different way. I mean, I conceptually know we should all be against cruelty to animals but then when you actually see what goes on, and then read more about slaughterhouses, et cetera, you recognize the moral imperative involved.

When you look at the history of the Western world, one of the historical phase transitions was the destruction of early pagan culture. And there was a time when women held aloft throughout the continent of Europe a sense of divine connection with the Earth, with the trees, with the waters, with the sky. And an early dispensation of Christianity was moving away from the notion of partnership with nature, to a very different paradigm in which nature was seen to have been created for mankind's utilitarian purposes.

Now even when you look at the natural order that way, humanity was instructed to be proper stewards of the world. But obviously, the way things unfolded… The hyper-capitalistic activity of big oil companies certainly does not display — and the laws that enabled that desecration to occur — do not reflect a reverence for the Earth or proper stewardship of it.

It was women who felt this natural connection to the Earth, who were the keepers of that flame and the consciousness of humanity at a particular place and a particular time. To me, feminism means not just standing for women, but standing for all feminine aspects of consciousness. And that means a greater sense of connection to nature, within ourselves, within each other, with animals, and with the Earth itself. So anything that empowers women, to me, increases our capacity to repair the Earth.

I’m an all-of-the-above type. But my natural holistic attitude towards things would be your second category. The first is transactional. Necessary, but not of themselves enough. Especially — I’m not an advocate for nuclear energy.

I don’t think of myself as an environmentalist; I think of myself as a human. You don’t have to call yourself an environmentalist to grieve what’s happening. Not that I wouldn’t call myself an environmentalist, it’s just I have enough labels, I don’t need another one.

I think we are disconnected from those things which are most important. We’ve lost over 50% of our bird species. Think how much more music there used to be in the air, how much more beauty.

I will tell you a moment that changed my life. It didn’t make me think, “Oh, I’m an environmentalist now.” But it impacted me in a way that nature never had before: When I went camping and hiking in the wilderness in Montana. That’s it.

I was one of those people — it’s almost embarrassing to admit this — but I thought, “Oh, yeah, I’ve seen pictures.” But once you go to certain places, you experience awe before nature. And destroying that mountaintop, oil drilling on that land, all the other things we do… You see the rivers, the creeks dying, the fish dying. Once again, it’s not because we were environmentalists. It’s because you’re a human with a modicum of connection to your soul.

East Palestine, Ohio, is a sacrifice zone. These things happen in the areas where people are the least able to absorb the pain. And I heard the fury, I saw the fury, I saw the decency, I saw the dignity, I saw the frustration, the bitterness, the despair, and in some cases, the hopelessness of people who had been not only neglected, abandoned, abused, and traumatized by Norfolk Southern, but had been re-traumatized by the neglect of their state and federal government.

I think we need to declare an emergency. I don’t say that lightly, by the way. And the powers of government should not be used like a bludgeon or meat cleaver. They should be used with appropriate nuance. Now, having said that, it has become clear to me that oil companies are not going to do this. The government, I believe, should act.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

On China’s rare earths, Bill Gates’ nuclear dream, and Texas renewables

Current conditions: Hurricane Melissa exploded in intensity over the warm Caribbean waters and has now strengthened into a major storm, potentially slamming into Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Jamaica as a Category 5 in the coming days • The Northeast is bracing for a potential nor’easter, which will be followed by a plunge in temperatures of as much as 15 degrees Fahrenheit lower than average • The northern Australian town of Julia Creek saw temperatures soar as high as 106 degrees.

Exxon Mobil filed a lawsuit against California late Friday on the grounds that two landmark new climate laws violate the oil giant’s free speech rights, The New York Times reported. The two laws would require thousands of large companies doing business in the state to calculate and report the greenhouse gas pollution created by the use of their products, so-called Scope 3 emissions. “The statutes compel Exxon Mobil to trumpet California’s preferred message even though Exxon Mobil believes the speech is misleading and misguided,” Exxon complained through its lawyers. California Governor Gavin Newsom’s office said the statutes “have already been upheld in court and we continue to have confidence in them.” He condemned the lawsuit, calling it “truly shocking that one of the biggest polluters on the planet would be opposed to transparency.”

China will delay introducing export controls on rare earths, an unnamed U.S. official told the Financial Times following two days of talks in Malaysia. For years, Beijing has been ratcheting up trade restrictions on the global supply of metals its industry dominates. But this month, China slapped the harshest controls yet on rare earths. In response, stocks in rare earth mining and refining companies soared. Despite what Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin called the “paradox of Trump’s critical mineral crusade” to mine even as he reduced demand from electric vehicle factories, “everybody wants to invest in critical minerals startups,” Heatmap’s Katie Brigham wrote. That — as frequent readers of this newsletter will recall — includes the federal government, which under the Trump administration has been taking equity stakes in major projects as part of deals for federal funding.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission rewarded Bill Gates’ next-generation reactor company, TerraPower, with its final environment impact statement last week. The next step in the construction permit process is a final safety evaluation that the company expects to receive by the end of this year. If everything goes according to plan, TerraPower could end up winning the race to build the nation’s first commercial reactor to use a coolant other than water, and do so at a former coal-fired plant in the country’s top coal-producing state. “The Natrium plant in Wyoming, Kemmerer Unit 1, is now the first advanced reactor technology to successfully complete an environmental impact statement for the NRC, bringing us another step closer to delivering America’s next nuclear power plant,” said TerraPower president and CEO Chris Levesque.

A judge gave New York Governor Kathy Hochul’s administration until February 6 to issue rules for its long-delayed cap-and-invest program, the Albany Times-Union reported. The government was supposed to issue the guidelines that would launch the program as early as 2024, but continuously pushed back the release. “Early outlines of New York’s cap and invest program indicate that regulators were considering a relatively low price ceiling on pollution, making it easier for companies to buy their way out of compliance with the cap,” Heatmap’s Emily Pontecorvo wrote in January.

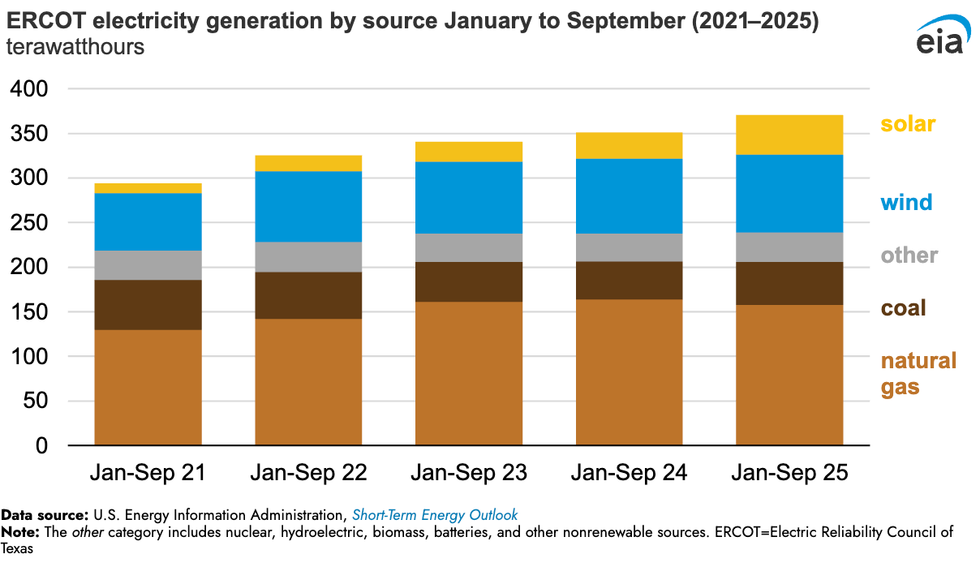

The Texas data center boom is being powered primarily with new wind, solar, and batteries, according to new analysis by the Energy Information Administration. Since 2021, electricity demand on the independent statewide grid operated by the Electric Reliability Council of Texas has soared. Over the past year, wind, solar, and batteries have been supplying that rising demand. Utility-scale solar generated 45 terawatt-hours of electricity in the first nine months of 2025. That’s 50% more than the same period in 2024 and nearly four times more than the same period in 2021. Wind generation, meanwhile, totaled 87 terawatt-hours for the first nine months of this year, up 4% from last year and 36% since 2021. “Together,” the analysis stated, “wind and solar generation met 36% of ERCOT’s electricity demand in the first nine months of 2025.”

The question isn’t whether the flames will come — it’s when, and what it will take to recover.

In the two decades following the turn of the millennium, wildfires came within three miles of an estimated 21.8 million Americans’ homes. That number — which has no doubt grown substantially in the five years since — represents about 6% of the nation’s population, including the survivors of some of the deadliest and most destructive fires in the country’s history. But it also includes millions of stories that never made headlines.

For every Paradise, California, and Lahaina, Hawaii, there were also dozens of uneventful evacuations, in which regular people attempted to navigate the confusing jargon of government notices and warnings. Others lost their homes in fires that were too insignificant to meet the thresholds for federal aid. And there are countless others who have decided, after too many close calls, to move somewhere else.

By any metric, costly, catastrophic, and increasingly urban wildfires are on the rise. Nearly a third of the U.S. population, however, lives in a county with a high or very high risk of wildfire, including over 60% of the counties in the West. But the shape of the recovery from those disasters in the weeks and months that follow is often that of a maze, featuring heart-rending decisions and forced hands. Understanding wildfire recovery is critical, though, for when the next disaster follows — which is why we’ve set out to explore the topic in depth.

The most immediate concerns for many in the weeks following a wildfire are financial. Homeowners are still required to pay the mortgage on homes that are nothing more than piles of ash — one study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia found that 90-day delinquencies rose 4% and prepayments rose 16% on properties that were damaged by wildfires. Because properties destroyed in fires often receive insurance settlements that are lower than the cost to fully replace their home, “households face strong incentives to apply insurance funds toward the mortgage balance instead of rebuilding, and the observed increase in prepayment represents a symptom of broader frictions in insurance markets that leave households with large financial losses in the aftermath of a natural disaster,” the researchers explain.

Indeed, many people who believed they had adequate insurance only discover after a fire that their coverage limits are lower than 75% of their home’s actual replacement costs, putting them in the category of the underinsured. Homeowners still grappling with the loss of their residence and possessions are also left to navigate reams of required paperwork to get their money, a project one fire victim likened to having a “part-time job.” It’s not uncommon for fire survivors to wait months or even years for payouts, or to find that necessary steps to rebuilding, such as asbestos testing and dead tree removals, aren’t covered. Just last week, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed a new law requiring insurers to pay at least 60% of a homeowner’s personal property coverage on a total loss without a detailed inventory, up to $350,000. The original proposal called for a 100% payout, but faced intense insurance industry blowback .

Even if your home doesn’t burn to the ground, you might be affected by the aftermath of a nearby fire. In California, a fifth of homes in the highest-risk wildfire areas have lost insurance coverage since 2019, while premiums in those same regions have increased by 42%. Insurers’ jitters have overflowedspilled over into other Western states like Washington, where there are fewer at-risk properties than in California — 16% compared to 41% — but premiums have similarly doubled in some cases due to the perceived hazardrisks.

Some experts argue that people should be priced out of the wildland-urban interface and that managed retreat will help prevent future tragedies. But as I report in my story on fire victims who’ve decided not to rebuild, that’s easier said than done. There are only three states where insured homeowners have the legal right to replace a wildfire-destroyed home by buying a new property instead of rebuilding, meaning many survivors end up shackled to a property that is likely to burn again.

The financial maze, of course, is only one aspect of recovery — the physical and mental health repercussions can also reverberate for years. A study that followed survivors of Australia’s Black Saturday bush fires in 2009, which killed over 170 people, found that five years after the disaster, a fifth of survivors still suffered from “serious mental health challenges” like post-traumatic stress disorder. In Lahaina, two years after the fire, nearly half of the children aged 10 to 17 who survived are suspected of coping with PTSD.

Federal firefighting practices continue to focus on containing fires as quickly as possible, to the detriment of less showy but possibly more effective solutions such as prescribed burns and limits on development in fire-prone areas. Some of this is due to the long history of fire suppression in the West, but it persists due to ongoing political and public pressure. Still, you can find small and promising steps forward for forest management in places like Paradise, where the recreation and park district director has scraped together funds to begin to build a buffer between an ecosystem that is meant to burn and survivors of one of the worst fires in California’s history.

In the four pieces that follow, I’ve attempted to explore the challenges of wildfire recovery in the weeks and months after the disaster itself. In doing so, I’ve spoken to firefighters, victims, researchers, and many others to learn more about what can be done to make future recoveries easier and more effective.

The bottom line, though, is that there is no way to fully prevent wildfires. We have to learn to live alongside them, and that means recovering smarter, too. It’s not the kind of glamorous work that attracts TV cameras and headlines; often, the real work of recovery occurs in the many months after the fire is extinguished. But it also might just make the difference.

Wildfire evacuation notices are notoriously confusing, and the stakes are life or death. But how to make them better is far from obvious.

How many different ways are there to say “go”? In the emergency management world, it can seem at times like there are dozens.

Does a “level 2” alert during a wildfire, for example, mean it’s time to get out? How about a “level II” alert? Most people understand that an “evacuation order” means “you better leave now,” but how is an “evacuation warning” any different? And does a text warning that “these zones should EVACUATE NOW: SIS-5111, SIS-5108, SIS-5117…” even apply to you?

As someone who covers wildfires, I’ve been baffled not only by how difficult evacuation notices can be to parse, but also by the extent to which they vary in form and content across the United States. There is no centralized place to look up evacuation information, and even trying to follow how a single fire develops can require hopping among jargon-filled fire management websites, regional Facebook pages, and emergency department X accounts — with some anxious looking-out-the-window-at-the-approaching-pillar-of-smoke mixed in.

Google and Apple Maps don’t incorporate evacuation zone data. Third-party emergency alert programs have low subscriber rates, and official government-issued Wireless Emergency Alerts, or WEAs — messages that trigger a loud tone and vibration to all enabled phones in a specific geographic region — are often delayed, faulty, or contain bad information, none of which is ideal in a scenario where people are making life-or-death decisions. The difficulty in accessing reliable information during fast-moving disasters like wildfires is especially aggravating when you consider that nearly everyone in America owns a smartphone, i.e. a portal to all the information in the world.

So why is it still so hard to learn when and where specific evacuation notices are in place, or if they even apply to you? The answer comes down to the decentralized nature of emergency management in the United States.

A downed power line sparks a fire on a day with a Red Flag Warning. A family driving nearby notices the column of smoke and calls to report it to 911. The first responders on the scene realize that the winds are fanning the flames toward a neighborhood, and the sheriff decides to issue a wildfire warning, communicating to the residents that they should be ready to leave at a moment’s notice. She radios her office — which is now fielding multiple calls asking for information about the smoke column — and asks for the one person in the office that day with training on the alert system to compose the message.

Scenarios like these are all too common. “The people who are put in the position of issuing the messages are doing 20 other things at the same time,” Jeannette Sutton, a researcher at the University at Albany’s Emergency and Risk Communication Message Testing Lab, told me. “They might have limited training and may not have had the opportunity to think about what the messages might contain — and then they’re told by an incident commander, Send this, and they’re like, Oh my God, what do I do?”

The primary way of issuing wildfire alerts is through WEAs, with 78,000 messages sent since 2012. Although partnerships between local emergency management officials, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Federal Communications Commission, and cellular and internet providers facilitate the technology, it’s local departments that determine the actual content of the message. Messaging limits force some departments to condense the details of complicated and evolving fire events into 90 characters or fewer. Typos, confusing wording, and jargon inevitably abound.

Emergency management teams often prefer to err on the side of sending too few messages rather than too many for fear of inducing information overload. “We’re so attached to our devices, whether it’s Instagram or Facebook or text messages, that it’s hard to separate the wheat from the chaff, so to speak — to make sure that we are getting the right information out there,” John Rabin, the vice president of disaster management at the consulting firm ICF International and a former assistant administrator at the Federal Emergency Management Agency, told me. “One of the challenges for local and state governments is how to bring [pertinent information] up and out, so that when they send those really important notifications for evacuations, they really resonate.”

But while writing an emergency alert is a bit of an art, active prose alone doesn’t ensure an effective evacuation message.

California’s Cal Fire has found success with the “Ready, Set, Go” program, designed by the International Association of Fire Chiefs, which uses an intuitive traffic light framework — “ready” is the prep work of putting together a go-bag and waiting for more news if a fire is in the vicinity, escalating to the “go” of the actual evacuation order. Parts of Washington and Oregon use similar three-tiered systems of evacuation “levels” ranging from 1 to 3. Other places, like Montana, rely on two-step “evacuation warnings” and “evacuation orders.”

Watch Duty, a website and app that surged in popularity during the Los Angeles fires earlier this year, doesn’t worry about oversharing. Most information on Watch Duty comes from volunteers, who monitor radio scanners, check wildfire cameras, and review official law enforcement announcements, then funnel the information to the organization’s small staff, who vet it before posting. Though WatchDuty volunteers and staff — many of whom are former emergency managers or fire personnel themselves — actively review and curate the information on the app, the organization still publishes far more frequent and iterative updates than most people are used to seeing and interpreting. As a result, some users and emergency managers have criticized Watch Duty for having too much information available, as a result.

The fact that Watch Duty was downloaded more than 2 million times during the L.A. fires, though, would seem to testify to the fact that people really are hungry for information in one easy-to-locate place. The app is now available in 22 states, with more than 250 volunteers working around the clock to keep wildfire information on the app up to date. John Clarke Mills, the app’s CEO and co-founder, has said he created the app out of “spite” over the fact that the government doesn’t have a better system in place for keeping people informed on wildfires.

“I’ve not known too many situations where not having information makes it better,” Katlyn Cummings, the community manager at Watch Duty, told me. But while the app’s philosophy is “rooted in transparency and trust with our users,” Cummings stressed to me that the app’s volunteers only use official and public sources of information for their updates and never include hearsay, separating it from other crowd-sourced community apps that have proved to be less than reliable.

Still, it takes an army of a dozen full-time staff and over 200 part-time volunteers, plus an obsessively orchestrated Slack channel to centralize the wildfire and evacuation updates — which might suggest why a more official version doesn’t exist yet, either from the government or a major tech company. Google Maps currently uses AI to visualize the boundaries of wildfires, but stops short of showing users the borders of local evacuation zones (though it will route you around known road closures). A spokesperson for Google also pointed me toward a feature in Maps that shares news articles, information from local authorities, and emergency numbers when users are in “the immediate vicinity” of an actively unfolding natural disaster — a kind of do-it-yourself Watch Duty. The company declined to comment on the record about why Maps specifically excludes evacuation zones. Apple did not respond to a request for comment.

There is, of course, a major caveat to the usefulness of Watch Duty.

Users of the app tend to be a self-selecting group of hyper-plugged-in digital natives who are savvy enough to download it or otherwise know to visit the website during an unfolding emergency. As Rabin, the former FEMA official, pointed out, Watch Duty users aren’t the population that first responders are most concerned about — they’re like “Boy Scouts,” he said, because they’re “always prepared.” They’re the ones who already know what’s going on. “It’s reaching the folks that aren’t paying attention that is the big challenge,” he told me.

The older adult population is the most vulnerable in cases of wildfire. Death tolls often skew disproportionately toward the elderly; of the 30 people who died in the Los Angeles fires in January, for example, all but two were over 60 or disabled, with the average age of the deceased 77, the San Francisco Chronicle reported. Part of that is because adults 65 and older are more likely to have physical impairments that make quick or unplanned evacuations challenging. Social and technological isolation are also factors — yes, almost everyone in America has a smartphone, but that includes just 80% of those 65 and older, and only 26% of the older adult population feels “very confident” using computers or smartphones. According to an extensive 2024 report on how extreme weather impacts older adults by CNA, an independent, nonprofit research organization, “Evacuation information, including orders, is not uniformly communicated in ways and via media that are accessible to older adults or those with access and functional needs.”

Sutton, the emergency warning researcher, also cautioned that more information isn’t always better. Similar to the way scary medical test results might appear in a health portal before a doctor has a chance to review them with you (and calm you down), wildfire information shared without context or interpretation from emergency management officials means the public is “making assumptions based upon what they see on Watch Duty without actually having those official messages coming from the public officials who are responsible for issuing those messages,” she said. One role of emergency managers is to translate the raw, on-the-ground information into actionable guidance. Absent that filter, panic is probable, which could lead to uncontrollable evacuation traffic or exacerbate alert fatigue. Alternatively, people might choose to opt out of future alerts or stop checking for updates.

Sutton, though she’s a strong advocate of creating standardized language for emergency alerts — “It would be wonderful if we had consistent language that was agreed upon” between departments, she told me — was ultimately skeptical of centralizing the emergency alert system under a large agency like FEMA. “The movement of wildfires is so fast, and it requires knowledge of the local communities and the local terrain as well as meteorological knowledge,” she said. “Alerts and warnings really should be local.”

The greater emphasis, Sutton stressed, should be on providing emergency managers with the training they need to communicate quickly, concisely, and effectively with the tools they already have.

The high wire act of emergency communications, though, is that while clear and regionally informed messages are critical during life-or-death situations, it also falls on residents in fire-risk areas to be ready to receive them. California first adopted the “Ready, Set, Go” framework in 2009, and it has spent an undisclosed amount of money over the years on a sustained messaging blitz to the public. (Cal Fire’s “land use planning and public education budget is estimated at $16 million, and funds things like the updated ad spots it released as recently as this August.) Still, there is evidence that even that has not been enough — and Cal Fire is the best-resourced firefighting agency in the country, setting the gold standard for an evacuation messaging campaign.

Drills and test messages are one way to bring residents up to speed, but participation is typically very low. Many communities and residents living in wildfire-risk areas continue to treat the threat with low urgency — something to get around to one day. But whether they’re coming from your local emergency management department or the White House itself, emergency notices are only as effective as the public is willing and able to heed them.