You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Who gets to block an energy project?

One of the longest-running environmental controversies of Joe Biden’s presidency is now over, but it presages much bigger controversies to come.

Last week, the Supreme Court cleared the way for the Mountain Valley Pipeline, a 303-mile natural gas project that will link West Virginia’s booming gas fields to the East Coast’s mainline gas infrastructure. The justices lifted a halt on the project that had been imposed by a lower court. In doing so, they all but guaranteed that the project will get built.

But even if the Mountain Valley Pipeline case is over, the issues and questions at the center of the dispute are not. And they suggest that a profound and unanswered tension sits at the heart of environmental and climate law — one that concerns not only conservation, but the very nature of American democracy as well.

While environmental advocates have fought the pipeline for years, it only became a national issue when Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia began to champion the pipeline last year. He insisted that the Biden administration back the project in exchange for his support of Biden’s flagship climate and spending bill, which became the Inflation Reduction Act.

After several failed efforts, Manchin finally found a way to help the pipeline this spring, when he got Congress to automatically approve the project as part of the bipartisan deal to raise the debt ceiling. The Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 — better known as the debt-ceiling deal — ordered federal agencies to issue every outstanding permit necessary for the pipeline’s construction. It declared that those permits could not be challenged in court.

Furthermore, it said that legal challenges to this accelerated decision could not be heard by the Fourth Circuit, the appeals court with jurisdiction over West Virginia, but only by the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals. The D.C. Circuit is often described as the country’s second most powerful court; more saliently, fewer of its judges were appointed by Democratic presidents.

And that seemed like the end of the story. But in June, the Sierra Club and other environmentalist groups sued to block the Mountain Valley Pipeline again. They now alleged that Congress had violated a key Constitutional idea — the separation of powers — by rushing to approve the pipeline.

Specifically, they argued that the debt-ceiling deal violated a 151-year-old case called United States v. Klein, or just Klein for short. In that case, which revolved around several hundred cotton bales seized in Mississippi during the Civil War, the Supreme Court ruled that Congress could not pass a law that forced a court to rule on a case in a certain way. In other words, Congress may not pass a law that says: If Smith sues Jones, Smith wins.

The Sierra Club and others argue that Congress violated Klein when it automatically approved the pipeline in the debt-ceiling bill. The pipeline had been mired in permit-related lawsuits in the Fourth Circuit for years; its construction has led to dozens of alleged water-quality violations. So when Congress granted those permit approvals anyway, it was essentially doing an end-run around the appeals court. That was a clear-cut violation of Klein, environmentalists argue.

Is it so simple? In a brief supporting the pipeline, Laborer’s International Union of America argues that Congress acted entirely within its authority. Congress has essentially unlimited authority to authorize agency actions and revise court jurisdiction, the union says.

But here is the rub. To make their case, environmentalists appealed to Chief Justice John Roberts — specifically a dissent he wrote back in 2018.

That year, the Court declined to strike down an Obama-era law that told courts to “promptly dismiss” any lawsuits challenging a tribal casino in Michigan. But the majority could not agree about why, and three conservative justices — led by Roberts — dissented, arguing that the Obama-era law violated Klein because it forced the Court’s hand on a lawsuit, even if the lawsuit in question had not been filed yet.

In their case against the pipeline, the environmentalists urged the Court to adopt the logic of that dissent. And that may reveal something surprising about the tack taken by environmental groups here: Their arguments draw from what has increasingly come to seem like a conservative approach to Constitutional law. And while there are understandable reasons for this, it shows that the environmental movement may be facing a deeper crisis than it realizes. The questions now confronting the climate movement go to the center of questions over American democracy.

Above all: Who gets to rule in the American republic, and who gets to determine what is and isn’t constitutional? This is a live debate, and it goes to the center of contemporary fights over permitting reform. It is worth dwelling on for a moment.

The standard historical line is the Supreme Court, above all, decides what is and isn’t Constitutional — a power that it has claimed for itself since Marbury v. Madison in 1803.

But there is another tradition in American life, which holds that the American people, not the justices, are the final arbiter of constitutionality. President Abraham Lincoln backed this view in the run-up to the Civil War. And so did the men who created the Klein crisis.

Klein did not come out of nowhere. The case emerged during one of the most wrenching moments in our Constitutional history, when radicals and moderates battled over the meaning of the Civil War in the wake of Lincoln’s assassination.

On one side, Radical Republicans in Congress wanted to enshrine equality at the heart of the American republic, protecting the economic and civil freedoms of newly emancipated Black people and harshly punishing their traitorous Southern enslavers. On the other, moderate Republicans and Democrats sought a more reconciliatory approach to Reconstruction, welcoming former Confederate elites back into American life.

This is the background of Klein. When Congress passed the 1870 law that provoked the Klein lawsuit, it sought to prevent ex-Confederates from claiming federal money as compensation for their losses. It wanted to block a man named John Klein from being paid for cotton bales seized from his client during the Civil War, specifically because Congress believed that his client had been part of the rebellion and therefore did not deserve federal funds.

But that was part of a much broader fight between Congress, the White House, and the Supreme Court, in which radical Republican lawmakers sought to assert the people’s — and therefore Congress’s — authority to govern the other branches. Since the people created the Constitution, radicals argued, then the people had final authority over the courts that it made. “It would be a sad day for American institutions and for the sacred cause of Republican Governments if any tribunal in this land, created by the will of the people, was above and superior to the people’s power,” Representative John Bingham, an Ohio radical and the leading author of the Fourteenth Amendment, said.

That theory was revived 60 years later, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt moved to rein in a Supreme Court that kept striking down his New Deal programs. He proposed packing the court with more favorable justices, arguing that the three branches of the Constitution were like a team of three horses pulling a wagon. “It is the American people themselves who are in the driver’s seat,” he said, and therefore the people who should determine the make-up of the Court.

Although Roosevelt’s packing scheme failed, it resulted in one of the Court’s more conservative justices switching to become a more reliably pro-New Deal vote. And since Democrats controlled the Senate for all but four of the following 43 years, the Court lurched in a more liberal direction through much of the 20th century. By the 1990s, the judiciary was the favored branch of establishment liberalism, an august arbiter of civil protections as enacted in Brown v. Board of Education, Loving v. Virginia, and Roe v. Wade.

No longer. Faced with the most conservative Supreme Court in 90 years, progressives have rediscovered this forgotten controversy in the Constitution. Congress, they argue, has the power and duty to regulate the Supreme Court when it strays too far from popular will. The text of the Constitution allows Congress to set exceptions to the Court’s “appellate jurisdiction,” meaning that it could simply prevent the Court from ruling on a given topic, such as abortion or climate change.

Progressives frame this claim in small-d democratic terms, framing the Supreme Court and the electoral college as institutions designed to rob majorities of the ability to govern. “As recent events have made clear, powerful reactionaries are waging a successful war against American democracy using the countermajoritarian institutions of the American political system,” the liberal columnist Jamele Bouie wrote in The New York Times last year. But “the Constitution gives our elected officials the power to restrain a lawless Supreme Court,” he added, even if it might “spark a constitutional crisis over the power and authority of Congress.”

Conservatives have noticed this push. Last week, Justice Samuel Alito argued that Congress has no ability whatsoever to set limits on the Court’s behavior. “I know this is a controversial view, but I’m willing to say it,” Alito told The Wall Street Journal. “No provision in the Constitution gives them the authority to regulate the Supreme Court — period.”

Although Alito is speaking in broader terms, his enmity gets at the simmering Constitutional dilemma at the heart of Klein, the precedent that environmentalists are citing to try to block the Mountain Valley Pipeline. When Congress approved the pipeline earlier this year, was it expressing a democratic view that must be respected by the court system (even if climate activists don’t like it)? Or was Congress instead running roughshod over due process and violating the separation of powers?

These are not academic questions. Although Congress intervened to approve a fossil-fuel pipeline this year, it could just as easily intervene to approve clean-energy infrastructure in the future. Across the country, renewable projects and long-distance electricity transmission have been slowed down by environmental lawsuits and permitting fights; even the Sierra Club has recognized the “NIMBY threat to renewable energy.” If lawsuits were to imperil, say, a major offshore wind project, should a Democratic Congress resolve that fight by granting permit approvals by fiat — or should environmentalists reject that intervention, too, as illegitimate? Under the logic of the anti-pipeline lawsuit, granting permit approvals to any stalled energy project — whether fossil or clean — would violate Klein.

These questions matter because there is no near-term political situation in which Congress and the Supreme Court will only do good things for the climate and not bad things. But there is no way to judge them without making a political assessment: Is Congress likely to expedite a renewable project? Given Democrats’ zeal for tackling climate change, such a thing doesn’t seem ludicrous to me. But if environmentalists had won their case against the pipeline, then lawmakers’ hands would be tied in the future: They could not approve a wind farm, solar plant, or nuclear reactor in the same way that they tried to rubber-stamp the MVP. They would have to wait, instead, for the legal process to run its course.

We should be clear, here, that just because the Sierra Club and others pursued a conservative line of argument in this case does not mean that they are themselves reactionary. Their job — unlike that of politicians or pundits — is to win lawsuits. They have to fight on the terrain that politics has given them, and since that terrain tilts to the right today, they are sometimes going to advance right-leaning arguments.

But the broader environmental movement, which emerged in the 1950s and '60s as a cross-partisan, mass democratic campaign, should be careful not to confuse its goals with those of the elite legal movement. The question hangs over climate policy, permitting reform, and the entire challenge of decarbonization: How should climate advocates balance the goals of decarbonization and democracy? What does democracy even mean for the environment, a term that encompasses the water quality of a stream and the carbon intensity of the atmosphere? In the 21st century, how should Americans exert their will to reshape the land, protect the environment, and power their society?

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

And more on the week’s biggest conflicts around renewable energy projects.

1. Jackson County, Kansas – A judge has rejected a Hail Mary lawsuit to kill a single solar farm over it benefiting from the Inflation Reduction Act, siding with arguments from a somewhat unexpected source — the Trump administration’s Justice Department — which argued that projects qualifying for tax credits do not require federal environmental reviews.

2. Portage County, Wisconsin – The largest solar project in the Badger State is now one step closer to construction after settling with environmentalists concerned about impacts to the Greater Prairie Chicken, an imperiled bird species beloved in wildlife conservation circles.

3. Imperial County, California – The board of directors for the agriculture-saturated Imperial Irrigation District in southern California has approved a resolution opposing solar projects on farmland.

4. New England – Offshore wind opponents are starting to win big in state negotiations with developers, as officials once committed to the energy sources delay final decisions on maintaining contracts.

5. Barren County, Kentucky – Remember the National Park fighting the solar farm? We may see a resolution to that conflict later this month.

6. Washington County, Arkansas – It seems that RES’ efforts to build a wind farm here are leading the county to face calls for a blanket moratorium.

7. Westchester County, New York – Yet another resort town in New York may be saying “no” to battery storage over fire risks.

Solar and wind projects are getting swept up in the blowback to data center construction, presenting a risk to renewable energy companies who are hoping to ride the rise of AI in an otherwise difficult moment for the industry.

The American data center boom is going to demand an enormous amount of electricity and renewables developers believe much of it will come from solar and wind. But while these types of energy generation may be more easily constructed than, say, a fossil power plant, it doesn’t necessarily mean a connection to a data center will make a renewable project more popular. Not to mention data centers in rural areas face complaints that overlap with prominent arguments against solar and wind – like noise and impacts to water and farmland – which is leading to unfavorable outcomes for renewable energy developers more broadly when a community turns against a data center.

“This is something that we’re just starting to see,” said Matthew Eisenson, a senior fellow with the Renewable Energy Legal Defense Initiative at the Columbia University Sabin Center for Climate Change Law. “It’s one thing for environmentalists to support wind and solar projects if the idea is that those projects will eventually replace coal power plants. But it’s another thing if those projects are purely being built to meet incremental demand from data centers.”

We’ve started to see evidence of this backlash in certain resort towns fearful of a new tech industry presence and the conflicts over transmission lines in Maryland. But it is most prominent in Virginia, ground zero for American hyperscaler data centers. As we’ve previously discussed in The Fight, rural Virginia is increasingly one of the hardest places to get approval for a solar farm in the U.S., and while there are many reasons the industry is facing issues there, a significant one is the state’s data center boom.

I spent weeks digging into the example of Mecklenburg County, where the local Board of Supervisors in May indefinitely banned new solar projects and is rejecting those that were in the middle of permitting when the decision came down. It’s also the site of a growing data center footprint. Microsoft, which already had a base of operations in the county’s town of Boydton, is in the process of building a giant data center hub with three buildings and an enormous amount of energy demand. It’s this sudden buildup of tech industry infrastructure that is by all appearances driving a backlash to renewable energy in the county, a place that already had a pre-existing high opposition risk in the Heatmap Pro database.

It’s not just data centers causing the ban in Mecklenburg, but it’s worth paying attention to how the fight over Big Tech and solar has overlapped in the county, where Sierra Club’s Virginia Chapter has worked locally to fight data center growth with a grassroots citizens group, Friends of the Meherrin River, that was a key supporter of the solar moratorium, too.

In a conversation with me this week, Tim Cywinski, communications director for the state’s Sierra Club chapter, told me municipal leaders like those in Mecklenburg are starting to group together renewables and data centers because, simply put, rural communities enter into conversations with these outsider business segments with a heavy dose of skepticism. This distrust can then be compounded when errors are made, such as when one utility-scale solar farm – Geenex’s Grasshopper project – apparently polluted a nearby creek after soil erosion issues during construction, a problem project operator Dominion Energy later acknowledged and has continued to be a pain point for renewables developers in the county.

“I don’t think the planning that has been presented to rural America has been adequate enough,” the Richmond-based advocate said. “Has solar kind of messed up in a lot of areas in rural America? Yeah, and that’s given those communities an excuse to roll them in with a lot of other bad stuff.”

Cywinski – who describes himself as “not your typical environmentalist” – says the data center space has done a worse job at community engagement than renewables developers in Virginia, and that the opposition against data center projects in places like Chesapeake and Fauquier is more intense, widespread, and popular than the opposition to renewables he’s seeing play out across the Commonwealth.

But, he added, he doesn’t believe the fight against data centers is “mutually exclusive” from conflicts over solar. “I’m not going to tout the gospel of solar while I’m trying to fight a data center for these people because it’s about listening to them, hearing their concerns, and then not telling them what to say but trying to help them elevate their perspective and their concerns,” Cywinski said.

As someone who spends a lot of time speaking with communities resisting solar and trying to best understand their concerns, I agree with Cywinksi: the conflict over data centers speaks to the heart of the rural vs. renewables divide, and it offers a warning shot to anyone thinking AI will help make solar and wind more popular.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act is one signature away from becoming law and drastically changing the economics of renewables development in the U.S. That doesn’t mean decarbonization is over, experts told Heatmap, but it certainly doesn’t help.

What do we do now?

That’s the question people across the climate change and clean energy communities are asking themselves now that Congress has passed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which would slash most of the tax credits and subsidies for clean energy established under the Inflation Reduction Act.

Preliminary data from Princeton University’s REPEAT Project (led by Heatmap contributor Jesse Jenkins) forecasts that said bill will have a dramatic effect on the deployment of clean energy in the U.S., including reducing new solar and wind capacity additions by almost over 40 gigawatts over the next five years, and by about 300 gigawatts over the next 10. That would be enough to power 150 of Meta’s largest planned data centers by 2035.

But clean energy development will hardly grind to a halt. While much of the bill’s implementation is in question, the bill as written allows for several more years of tax credit eligibility for wind and solar projects and another year to qualify for them by starting construction. Nuclear, geothermal, and batteries can claim tax credits into the 2030s.

Shares in NextEra, which has one of the largest clean energy development businesses, have risen slightly this year and are down just 6% since the 2024 election. Shares in First Solar, the American solar manufacturer, are up substantially Thursday from a day prior and are about flat for the year, which may be a sign of investors’ belief that buyer demand for solar panels will persist — or optimism that the OBBBA’s punishing foreign entity of concern requirements will drive developers into the company’s arms.

Partisan reversals are hardly new to climate policy. The first Trump administration gleefully pulled the rug from under the Obama administration’s power plant emissions rules, and the second has been thorough so far in its assault on Biden’s attempt to replace them, along with tailpipe emissions standards and mileage standards for vehicles, and of course, the IRA.

Even so, there are ways the U.S. can reduce the volatility for businesses that are caught in the undertow. “Over the past 10 to 20 years, climate advocates have focused very heavily on D.C. as the driver of climate action and, to a lesser extent, California as a back-stop,” Hannah Safford, who was director for transportation and resilience in the Biden White House and is now associate director of climate and environment at the Federation of American Scientists, told Heatmap. “Pursuing a top down approach — some of that has worked, a lot of it hasn’t.”

In today’s environment, especially, where recognition of the need for action on climate change is so politically one-sided, it “makes sense for subnational, non-regulatory forces and market forces to drive progress,” Safford said. As an example, she pointed to the fall in emissions from the power sector since the late 2000s, despite no power plant emissions rule ever actually being in force.

“That tells you something about the capacity to deliver progress on outcomes you want,” she said.

Still, industry groups worry that after the wild swing between the 2022 IRA and the 2025 OBBBA, the U.S. has done permanent damage to its reputation as a business-friendly environment. Since continued swings at the federal level may be inevitable, building back that trust and creating certainty is “about finding ballasts,” Harry Godfrey, the managing director for Advanced Energy United’s federal priorities team, told Heatmap.

The first ballast groups like AEU will be looking to shore up is state policy. “States have to step up and take a leadership role,” he said, particularly in the areas that were gutted by Trump’s tax bill — residential energy efficiency and electrification, transportation and electric vehicles, and transmission.

State support could come in the form of tax credits, but that’s not the only tool that would create more certainty for businesses — considering the budget cuts states will face as a result of Trump’s tax bill, it also might not be an option. But a lot can be accomplished through legislative action, executive action, regulatory reform, and utility ratemaking, Godfrey said. He cited new virtual power plant pilot programs in Virginia and Colorado, which will require further regulatory work to “to get that market right.”

A lot of work can be done within states, as well, to make their deployment of clean energy more efficient and faster. Tyler Norris, a fellow at Duke University's Nicholas School of the Environment, pointed to Texas’ “connect and manage” model for connecting renewables to the grid, which allows projects to come online much more quickly than in the rest of the country. That’s because the state’s electricity market, ERCOT, does a much more limited study of what grid upgrades are needed to connect a project to the grid, and is generally more tolerant of curtailing generation (i.e. not letting power get to the grid at certain times) than other markets.

“As Texas continues to outpace other markets in generator and load interconnections, even in the absence of renewable tax credits, it seems increasingly plausible that developers and policymakers may conclude that deeper reform is needed to the non-ERCOT electricity markets,” Norris told Heatmap in an email.

At the federal level, there’s still a chance for, yes, bipartisan permitting reform, which could accelerate the buildout of all kinds of energy projects by shortening their development timelines and helping bring down costs, Xan Fishman, senior managing director of the energy program at the Bipartisan Policy Center, told Heatmap. “Whether you care about energy and costs and affordability and reliability or you care about emissions, the next priority should be permitting reform,” he said.

And Godfrey hasn’t given up on tax credits as a viable tool at the federal level, either. “If you told me in mid-November what this bill would look like today, while I’d still be like, Ugh, that hurts, and that hurts, and that hurts, I would say I would have expected more rollbacks. I would have expected deeper cuts,” he told Heatmap. Ultimately, many of the Inflation Reduction Act’s tax credits will stick around in some form, although we’ve yet to see how hard the new foreign sourcing requirements will hit prospective projects.

While many observers ruefully predicted that the letter-writing moderate Republicans in the House and Senate would fold and support whatever their respective majorities came up with — which they did, with the sole exception of Pennsylvania Republican Brian Fitzpatrick — the bill also evolved over time with input from those in the GOP who are not openly hostile to the clean energy industry.

“You are already seeing people take real risk on the Republican side pushing for clean energy,” Safford said, pointing to Alaska Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski, who opposed the new excise tax on wind and solar added to the Senate bill, which earned her vote after it was removed.

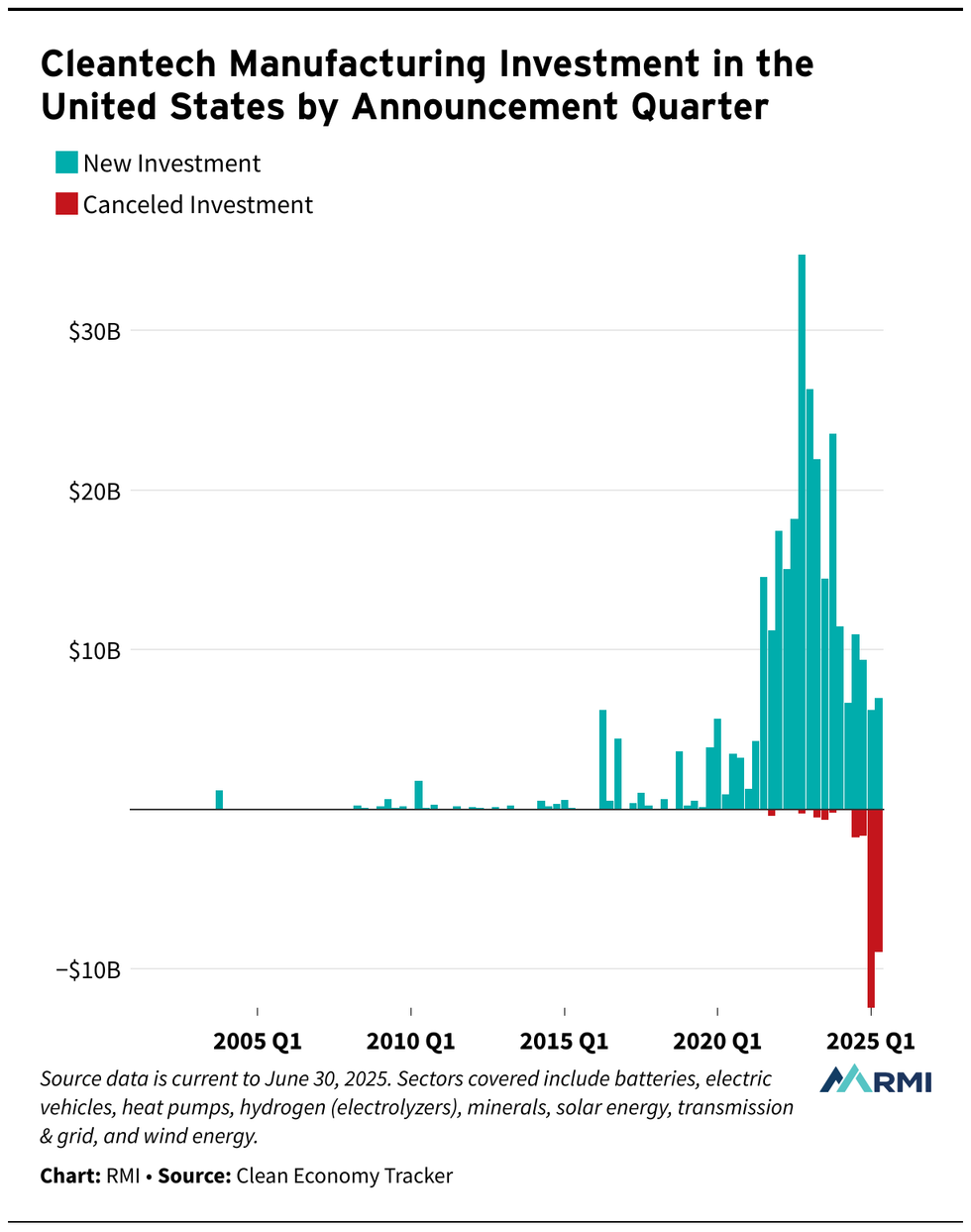

Some damage has already been done, however. Canceled clean energy investments adds up to $23 billion so far this year, compared to just $3 billion in all of 2024, according to the decarbonization think tank RMI. And that’s before OBBBA hits Trump’s desk.

The start-and-stop nature of the Inflation Reduction Act may lead some companies, states, local government and nonprofits to become leery of engaging with a big federal government climate policy again.

“People are going to be nervous about it for sure,” Safford said. “The climate policy of the future has to be polycentric. Even if you have the political opportunity to make a big swing again, people will be pretty gun shy. You will need to pursue a polycentric approach.”

But to Godfrey, all the back and forth over the tax credits, plus the fact that Republicans stood up to defend them in the 11th hour, indicates that there is a broader bipartisan consensus emerging around using them as a tool for certain energy and domestic manufacturing goals. A future administration should think about refinements that will create more enduring policy but not set out in a totally new direction, he said.

Albert Gore, the executive director of the Zero Emissions Transportation Association, was similarly optimistic that tax credits or similar incentives could work again in the future — especially as more people gain experience with electric vehicles, batteries, and other advanced clean energy technologies in their daily lives. “The question is, how do you generate sufficient political will to implement that and defend it?” he told Heatmap. “And that depends on how big of an economic impact does it have, and what does it mean to the American people?”

Ultimately, Fishman said, the subsidy on-off switch is the risk that comes with doing major policy on a strictly partisan basis.

“There was a lot of value in these 10-year timelines [for tax credits in the IRA] in terms of business certainty, instead of one- or two- year extensions,” Fishman told Heatmap. “The downside that came with that is that it became affiliated with one party. It was seen as a partisan effort, and it took something that was bipartisan and put a partisan sheen on it.”

The fight for tax credits may also not be over yet. Before passage of the IRA, tax credits for wind and solar were often extended in a herky-jerky bipartisan fashion, where Democrats who supported clean energy in general and Republicans who supported it in their districts could team up to extend them.

“You can see a world where we have more action on clean energy tax credits to enhance, extend and expand them in a future congress,” Fishman told Heatmap. “The starting point for Republican leadership, it seemed, was completely eliminating the tax credits in this bill. That’s not what they ended up doing.”