You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

The average anti-wind farm protest is made up of just 23 people.

All across North America, more and more wind farm projects are meeting local opposition.

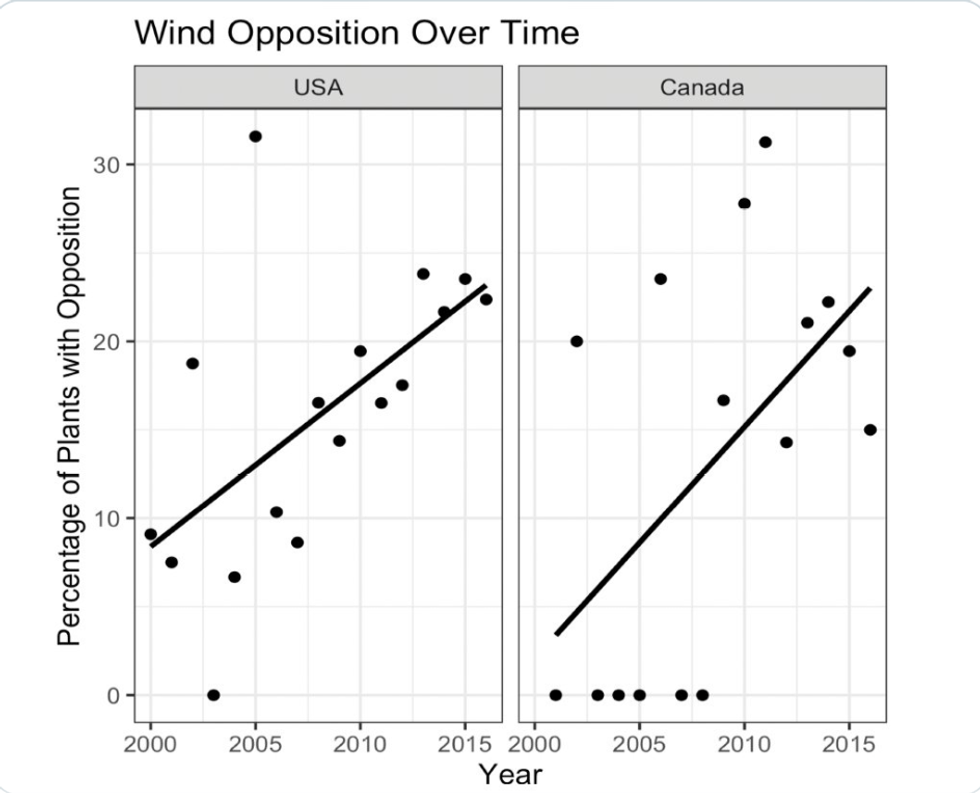

That’s the conclusion of a new study, published earlier this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, that looked at more than 1,400 wind farms proposed in the United States and Canada. The authors found that from 2000 to 2016, local opposition to proposed wind farms got successively worse in both countries.

“In the early 2000s, only around 1 in 10 wind projects was opposed. In 2016, it was closer to one in four,” Leah Stokes, an author of the study and a political-science professor at the University of California at Santa Barbara, wrote on the social network X.

The opposition has probably only gotten worse since then, she added.

Although the study stopped in 2016, a few things stand out about its findings that remain useful to climate debates today.

First, the mechanism of the protests differed between the countries. While Canadians tended to oppose projects by holding physical protests, Americans sought recourse in the courts, using local and federal permitting and environmental rules to block the wind proposals. “In the United States, courts were the dominant mode of opposition, followed by legislation, then physical protest, then letters to the editor,” the authors write.

Second, few of the protests were very large. In the United States, the median anti-wind-farm protest was made up of just 23 people — barely enough to fill a kindergarten classroom. Only about 30 people made up the average Canadian protests. Many of these protests happened in richer, whiter areas, including in the Northeastern United States.

Stokes and her colleagues conclude that reveals what they call “energy privilege,” the ability of rich, largely white communities to stymie the energy transition. By slowing down or blocking wind farms, these protests keep fossil-fuel infrastructure operating for longer, they write. And since that old, dirty infrastructure is often located in poorer or marginalized communities, these protests essentially subject low-income and nonwhite people to more pollution for longer. (That’s the “privilege” part of “energy privilege.”)

I think that’s an important idea, but I would take it one step further. In her X thread, Stokes compared the tiny number of people who make up the anti-wind protests to the more than 50,000 climate activists who filled the streets of New York earlier this month. The anti-renewable movement is small, in other words, while the pro-climate movement is big.

But that mismatch reveals a more profound question about our environmental laws than progressives are always eager to address: How can fewer than two dozen people block a wind farm in the first place? Recent economic research and reporting has shown that the community input process — that is, the meeting-based process at the center of national and local permitting decisions — inherently benefits whiter and wealthier people. And that injustice only gets worse when the threat of a lawsuit is involved.

Get one great climate story in your inbox every day:

That’s because the community-input process exists to serve only those who have the time, money, and expertise to stage a rebellion. You can see that in Washington, D.C., where whiter and wealthier neighborhoods have been able to slow down the construction of affordable housing at a much higher pace than majority Black neighborhoods. Or you can see it in California, where residents have been able to use a state environmental law to block solar farms, public transit, and denser housing. Nevermind “energy privilege” — this is just “permitting privilege.”

Even worse, the longer that a given permitting fight lasts, the more the public seems to grow skeptical of the project in question. In New Jersey, for instance, most people supported the creation of an offshore wind industry for years. But as local fights over the industry grew in salience, and as outside money poured in, the public has soured on the proposal. Today, four in 10 New Jersey residents oppose building new offshore wind farms, according to a recent Monmouth University poll.

There may even be something about the community input that favors opponents of new infrastructure. In 2017, three Boston University economists found that the community-input process may attract people who want to block projects; on average, only 14.6% of people who show up to community meetings tend to favor a given project. That systematic privilege of the status quo is an existential problem for the climate movement. Remember: If the world is to stave off 1.5 degrees Celsius of climate change, it must build new infrastructure at an unprecedented scale.

This amounts to a profound crisis. Right now, America’s legal system gives wealthier, whiter communities — and a very persuasive fossil-fuel industry — a veto to block the clean-energy transition. It’s well past time for climate advocates to ask: Is that democratic? And if it isn’t, what should we do about it?

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Clean energy stocks were up after the court ruled that the president lacked legal authority to impose the trade barriers.

The Supreme Court struck down several of Donald Trump’s tariffs — the “fentanyl” tariffs on Canada, Mexico, and China and the worldwide “reciprocal” tariffs ostensibly designed to cure the trade deficit — on Friday morning, ruling that they are illegal under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act.

The actual details of refunding tariffs will have to be addressed by lower courts. Meanwhile, the White House has previewed plans to quickly reimpose tariffs under other, better-established authorities.

The tariffs have weighed heavily on clean energy manufacturers, with several companies’ share prices falling dramatically in the wake of the initial announcements in April and tariff discussion dominating subsequent earnings calls. Now there’s been a sigh of relief, although many analysts expected the Court to be extremely skeptical of the Trump administration’s legal arguments for the tariffs.

The iShares Global Clean Energy ETF was up almost 1%, and shares in the solar manufacturer First Solar and the inverter company Enphase were up over 5% and 3%, respectively.

First Solar initially seemed like a winner of the trade barriers, however the company said during its first quarter earnings call last year that the high tariff rate and uncertainty about future policy negatively affected investments it had made in Asia for the U.S. market. Enphase, the inverter and battery company, reported that its gross margins included five percentage points of negative impact from reciprocal tariffs.

Trump unveiled the reciprocal tariffs on April 2, a.k.a. “liberation day,” and they have dominated decisionmaking and investor sentiment for clean energy companies. Despite extensive efforts to build an American supply chain, many U.S. clean energy companies — especially if they deal with batteries or solar — are still often dependent on imports, especially from Asia and specifically China.

In an April earnings call, Tesla’s chief financial officer said that the impact of tariffs on the company’s energy business would be “outsized.” The turbine manufacturer GE Vernova predicted hundreds of millions of dollars of new costs.

Companies scrambled and accelerated their efforts to source products and supplies from the United States, or at least anywhere other than China.

Even though the tariffs were quickly dialed back following a brutal market reaction, costs that were still being felt through the end of last year. Tesla said during its January earnings call that it expected margins to shrink in its energy business due to “policy uncertainty” and the “cost of tariffs.”

Alphabet and Amazon each plan to spend a small-country-GDP’s worth of money this year.

Big tech is spending big on data centers — which means it’s also spending big on power.

Alphabet, the parent company of Google, announced Wednesday that it expects to spend $175 billion to $185 billion on capital expenditures this year. That estimate is about double what it spent in 2025, far north of Wall Street’s expected $121 billion, and somewhere between the gross domestic products of Ecuador and Morocco.

This is a “a massive investment in absolute terms,” Jefferies analyst Brent Thill wrote in a note to clients Thursday. “Jarringly large,” Guggenheim analyst Michael Morris wrote. With this announcement, total expected capital expenditures by Alphabet, Microsoft and Meta for 2026 are at $459 billion, according to Jefferies calculations — roughly the GDP of South Africa. If Alphabet’s spending comes in at the top end of its projected range, that would be a third larger than the “total data center spend across the 6 largest players only 3 years ago,” according to Brian Nowak, an analyst at Morgan Stanley.

And that was before Thursday, when Amazon told investors that it expects to spend “about $200 billion” on capital expenditures this year.

For Alphabet, this growth in capital expenditure will fund data center development to serve AI demand, just as it did last year. In 2025, “the vast majority of our capex was invested in technical infrastructure, approximately 60% of that investment in servers, and 40% in data centers and networking equipment,” chief financial officer Anat Ashkenazi said on the company’s earnings call.

The ramp up in data center capacity planned by the tech giants necessarily means more power demand. Google previewed its immense power needs late last year when it acquired the renewable developer Intersect for almost $5 billion.

When asked by an analyst during the company’s Wednesday earnings call “what keeps you up at night,” Alphabet chief executive Sundar Pichai said, “I think specifically at this moment, maybe the top question is definitely around capacity — all constraints, be it power, land, supply chain constraints. How do you ramp up to meet this extraordinary demand for this moment?”

One answer is to contract with utilities to build. The utility and renewable developer NextEra said during the company’s earnings call last week that it plans to bring on 15 gigawatts worth of power to serve datacenters over the next decade, “but I'll be disappointed if we don't double our goal and deliver at least 30 gigawatts through this channel by 2035,” NextEra chief executive John Ketchum said. (A single gigawatt can power about 800,000 homes).

The largest and most well-established technology companies — the Microsofts, the Alphabets, the Metas, and the Amazons — have various sustainability and clean energy commitments, meaning that all sorts of clean power (as well as a fair amount of natural gas) are likely to get even more investment as data center investment ramps up.

Jefferies analyst Julien Dumoulin-Smith described the Alphabet capex figure as “a utility tailwind,” specifically calling out NextEra, renewable developer Clearway Energy (which struck a $2.4 billion deal with Google for 1.2 gigawatts worth of projects earlier this year), utility Entergy (which is Google’s partner for $4 billion worth of projects in Arkansas), Kansas-based utility Evergy (which is working on a data center project in Kansas City with Google), and Wisconsin-based utility Alliant (which is working on data center projects with Google in Iowa).

If getting power for its data centers keeps Pichai up at night, there’s no lack of utility executives willing to answer his calls.

The offshore wind industry is now five-for-five against Trump’s orders to halt construction.

District Judge Royce Lamberth ruled Monday morning that Orsted could resume construction of the Sunrise Wind project off the coast of New England. This wasn’t a surprise considering Lamberth has previously ruled not once but twice in favor of Orsted continuing work on a separate offshore energy project, Revolution Wind, and the legal arguments were the same. It also comes after the Trump administration lost three other cases over these stop work orders, which were issued without warning shortly before Christmas on questionable national security grounds.

The stakes in this case couldn’t be more clear. If the government were to somehow prevail in one or more of these cases, it would potentially allow agencies to shut down any construction project underway using even the vaguest of national security claims. But as I have previously explained, that behavior is often a textbook violation of federal administrative procedure law.

Whether the Trump administration will appeal any of these rulings is now the most urgent question. There have been no indications that the administration intends to do so, and a review of the federal dockets indicates nothing has been filed yet.

The Department of Justice declined to comment on whether it would seek to appeal any or all of the rulings.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to reflect that the administration declined to comment.