You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Two things are true:

1. Levees are critical flood-control infrastructure.

2. We don’t really know what shape they’re in.

A glance at the website for the National Levee Database — which was developed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers as part of the National Levee Safety Program in the wake of Hurricane Katrina and does what it says on the can — shows nearly 25,000 miles of levees across all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam, hemming waterways on the edges of communities that 17 million Americans call home. Look a little further out and you’ll find that almost two-thirds of all Americans live in counties with levees in them, even if their homes aren’t directly protected by those levees.

But the database is full of gaps. Despite the ubiquity of levees, there’s still much we don’t know about them, starting with where they all are. According to the American Society of Civil Engineers’ 2021 Infrastructure Report Card (which, incidentally, gives America’s levees a D grade), the conditions of more than half of the levees in the database are unknown, while there are an additional 10,000 miles or so of levees that simply aren’t in the database at all — though most of them have very few, if any, people living behind them.

That latter number is up for debate, too: The 2017 Infrastructure Report Card estimated there are about 100,000 total miles of levees in the country, a number backed up by a 2022 study that used machine learning to map about 113,000 miles of potential levees, which would suggest the database is only about a quarter complete. That's a huge disparity, to put it mildly. The data gap could be something more like a breach.

“You have to know what you have in your pocket,” said Farshid Vahedifard, a professor of civil engineering at Mississippi State University who studies levees. “The first step to risk governance is awareness.”

In an email to Heatmap, a spokesperson for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers confirmed the number of levees in the National Levee Database, saying, “We think that these are the majority of functioning levees across the country with some gaps. We will continue to add to the National Levee Database as levees are built or stakeholders provide any new information.”

For many Americans, levees are the margins between the built and natural worlds. They’re the first line of defense against flooding, directing water away from communities and containing rivers and lakes when they threaten to spill over their banks. Many of them were originally built decades ago by farmers or landowners looking to protect their land, Vahedifard said, and went on to become the de facto flood control measures of the communities that happened to spring up behind them.

Climate change is going to affect levees in numerous ways. There is, to begin with, the obvious problem of more frequent and severe storms, which could lead to more chances of floods overtopping or even breaking through levees, as happened in Pajaro, California in March, leaving the majority of the town underwater.

But climate change can also undermine the infrastructure itself. Just 3% of the levees in the country are engineered floodwalls made of concrete, rock, or steel; the vast majority — 97%, according to the infrastructure report card — are earthen embankments, or what regular folks might call giant mounds of soil. Prolonged droughts can weaken the soil in those embankments, leaving them brittle and unable to stand up to intense flooding. Droughts also lead to more demand for groundwater, and removing that groundwater causes the earth under levees to subside, weakening their foundations and making them more vulnerable to breaches.

In an ideal world, every levee in the country would be upgraded and maintained according to rigorous engineering standards. But that takes time and immense amounts of money — the Army Corps of Engineers would need $21 billion to fix the high-risk levees in its portfolio alone, and those make up just 15 percent of the known levees in the country; the vast majority of the levees in the country are maintained by local governments and water management districts. That means making the levee database complete is even more crucial.

“Once we know the status, we can use some sort of a screening process to identify more vulnerable locations, like the hotspots,” Vahedifard said. “Then we can allocate existing resources and prioritize those areas.”

The National Levee Database and the National Levee Safety Program were created as part of the National Levee Safety Act, which Congress first authorized in 2007. But they have been consistently underfunded: According to the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), appropriators provided just $5 million of the $79 million per year that the National Levee Safety Program is authorized to receive. Fully funding the program would at least help close the data gap.

Education is also crucial. Many people who live behind levees don’t know about the potential risk to their communities, said Vahedifard, and educating them on how their lives can be affected by the boundaries of the waterways near them is just as important a resiliency tool as physically shoring up the levees themselves.

“No levee is flood-proof,” declares the second page of So, You Live Behind a Levee!, a jauntily-named handbook for residents created by the ASCE, Army Corps of Engineers, and a conglomeration of partners. “Flooding will happen. Actions taken now will save lives and property.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Look more closely at today’s inflation figures and you’ll see it.

Inflation is slowing, but electricity bills are rising. While the below-expectations inflation figure reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics Wednesday morning — the consumer price index rose by just 0.1% in May, and 2.4% on the year — has been eagerly claimed by the Trump administration as a victory over inflation, a looming increase in electricity costs could complicate that story.

Consumer electricity prices rose 0.9% in May, and are up 4.5% in the past year. And it’s quite likely price increases will accelerate through the summer, thanks to America’s largest electricity market, PJM Interconnection. Significant hikes are expected or are already happening in many PJM states, including Maryland,New Jersey,Delaware, Pennsylvania, and Ohio with some utilities having said they would raise rates as soon as this month.

This has led to scrambling by state governments, with New Jersey announcing hundreds of millions of dollars of relief to alleviate rate increases as high as 20%. Maryland convinced one utility to spread out the increase over a few months.

While the dysfunctions of PJM are distinct and well known — new capacity additions have not matched fossil fuel retirements, leading to skyrocketing payments for those generators that can promise to be on in time of need — the overall supply and demand dynamics of the electricity industry could lead to a broader price squeeze.

“Trump and JD Vance can get off tweets about how there’s no inflation, but I don’t think they’ll feel that way in a week or two,” Skanda Amarnath, executive director of Employ America, told me.

And while the consumer price index is made up of, well, almost everything people buy, electricity price increases can have a broad effect on prices in general. “Everyone relies on energy,” Amarnath said. “Businesses that have higher costs can’t just eat it.” That means higher electricity prices may be translated into higher costs throughout the economy, a phenomenon known as “cost-push inflation.”

Aside from the particular dynamics of any one electricity market, there’s likely to be pressure on electricity prices across the country from the increased demand for energy from computing and factories. “There’s a big supply adjustment that’s going to have to happen, the data center demand dynamic is coming to roost,” Amarnath said.

Jefferies Chief U.S. Economist Thomas Simons said as much in a note to clients Wednesday. “Increased stress on the electrical grid from AI data centers, electric vehicle charging, and obligations to fund infrastructure and greenification projects have forced utilities to increase prices,” he wrote.

Of course, there’s also great uncertainty about the future path of electricity policy — namely, what happens to the Inflation Reduction Act — and what that means for prices.

The research group Energy Innovation has modeled the House reconciliation bill’s impact on the economy and the energy industry. The report finds that the bill “would dramatically slow deployment of new electricity generating capacity at a time of rapidly growing electricity demand.” That would result in higher electricity and energy prices across the board, with increases in household energy spending of around $150 per year in 2030, and more than $260 per year in 2035, due in part to a 6% increase in electricity prices by 2035.

In the near term, there’s likely not much policymakers can do about electricity prices, and therefore utility bills going up. Renewables are almost certainly the fastest way to get new electrons on the grid, but the completion of even existing projects could be thrown into doubt by the House bill’s strict “foreign entity of concern” rules, which try to extricate the renewables industry from its relationship with China.

“We’re running into a set of cost-push dynamics. It’s a hairy problem that no one is really wrapping their heads around,” Amarnath said. “It’s not really mainstream yet. It’s going to be.”

In some relief to American consumers, if not the planet, while it may be more expensive for them to cool their homes, it will be less expensive to get out of them: Gasoline prices fell 2.5% in May, according to the BLS, and are down 12% on the year.

Six months in, federal agencies are still refusing to grant crucial permits to wind developers.

Federal agencies are still refusing to process permit applications for onshore wind energy facilities nearly six months into the Trump administration, putting billions in energy infrastructure investments at risk.

On Trump’s first day in office, he issued two executive orders threatening the wind energy industry – one halting solar and wind approvals for 60 days and another commanding agencies to “not issue new or renewed approvals, rights of way, permits, leases or loans” for all wind projects until the completion of a new governmental review of the entire industry. As we were first to report, the solar pause was lifted in March and multiple solar projects have since been approved by the Bureau of Land Management. In addition, I learned in March that at least some transmission for wind farms sited on private lands may have a shot at getting federal permits, so it was unclear if some arms of the government might let wind projects proceed.

However, I have learned that the wind industry’s worst fears are indeed coming to pass. The Fish and Wildlife Service, which is responsible for approving any activity impacting endangered birds, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, tasked with greenlighting construction in federal wetlands, have simply stopped processing wind project permit applications after Trump’s orders – and the freeze appears immovable, unless something changes.

According to filings submitted to federal court Monday under penalty of perjury by Alliance for Clean Energy New York, at least three wind projects in the Empire State – Terra-Gen’s Prattsburgh Wind, Invenergy’s Canisteo Wind, and Apex’s Heritage Wind – have been unable to get the Army Corps or Fish and Wildlife Service to continue processing their permitting applications. In the filings, ACE NY states that land-based wind projects “cannot simply be put on a shelf for a few years until such time as the federal government may choose to resume permit review and issuance,” because “land leases expire, local permits and agreements expire, and as a result, the project must be terminated.”

While ACE NY’s filings discuss only these projects in New York, they describe the impacts as indicative of the national industry’s experience, and ACE NY’s executive director Marguerite Wells told me it is her understanding “that this is happening nationwide.”

“I can confirm that developers have conveyed to me that [the] Army Corps has stopped processing their applications specifically citing the wind ban,” Wells wrote in an email. “As I have understood it, the initial freeze covered both wind and solar projects, but the freeze was lifted for solar projects and not for wind projects.”

Lots of attention has been paid to Trump’s attacks on offshore wind, because those projects are sited entirely in federal waters. But while wind projects sited on private lands can hypothetically escape a federal review and keep sailing on through to operation, wind turbines are just so large in size that it’s hard to imagine that bird protection laws can’t apply to most of them. And that doesn’t account for wetlands, which seem to be now bedeviling multiple wind developers.

This means there’s an enormous economic risk in a six-month permitting pause, beyond impacts to future energy generation. The ACE NY filings state the impacts to New York alone represent more than $2 billion in capital investments, just in the land-based wind project pipeline, and there’s significant reason to believe other states are also experiencing similar risks. In a legal filing submitted by Democratic states challenging the executive order targeting wind, attorneys general listed at least three wind projects in Arizona – RWE’s Forged Ethic, AES’s West Camp, and Repsol’s Lava Run – as examples that may require approval from the federal government under the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act. As I’ve previously written, this is the same law that bird conservation advocates in Wyoming want Trump to use to reject wind proposals in their state, too.

The Fish and Wildlife Service and Army Corps of Engineers declined to comment after this story’s publication due to litigation on the matter. I also reached out to the developers involved in these projects to inquire about their commitments to these projects in light of the permitting pause. We’ll let you know if we hear back from them.

On power plant emissions, Fervo, and a UK nuclear plant

Current conditions: A week into Atlantic hurricane season, development in the basin looks “unfavorable through June” • Canadian wildfires have already burned more land than the annual average, at over 3.1 million hectares so far• Rescue efforts resumed Wednesday in the search for a school bus swept away by flash floods in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa.

The Environmental Protection Agency plans to announce on Wednesday the rollback of two major Biden-era power plant regulations, administration insiders told Bloomberg and Politico. The EPA will reportedly argue that the prior administration’s rules curbing carbon dioxide emissions at coal and gas plants were misplaced because the emissions “do not contribute significantly to dangerous pollution,” per The Guardian, despite research showing that the U.S. power sector has contributed 5% of all planet-warming pollution since 1990. The government will also reportedly argue that the carbon capture technology proposed by the prior administration to curb CO2 emissions at power plants is unproven and costly.

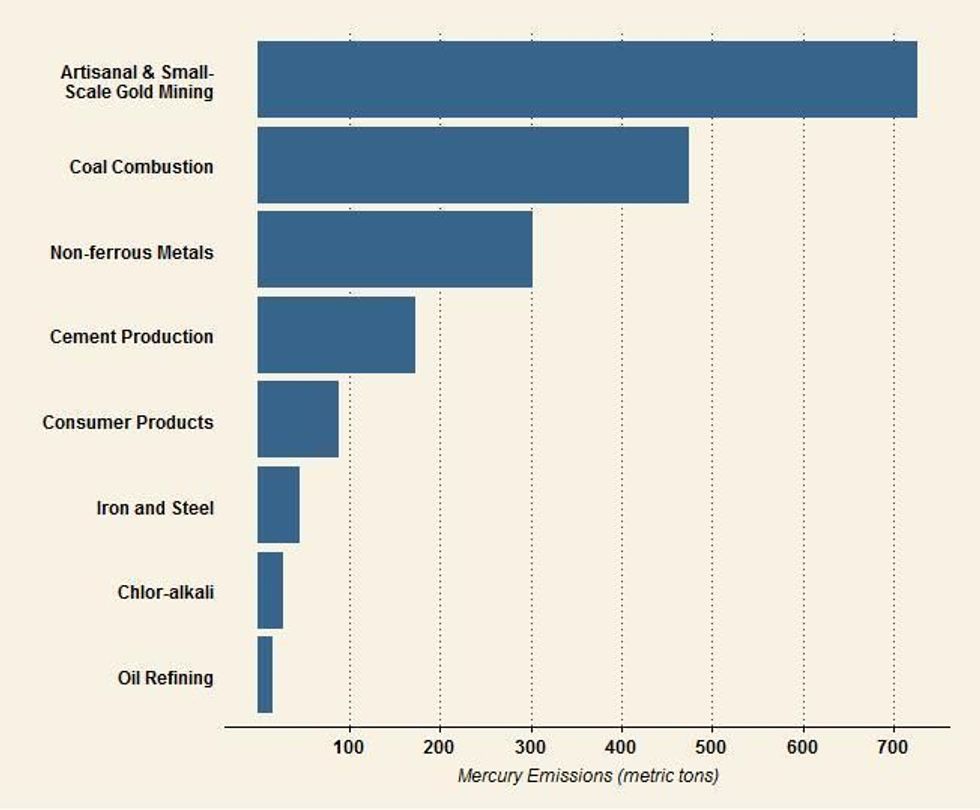

Similarly, the administration plans to soften limits on mercury emissions, which are released by burning coal, arguing that the Biden administration “improperly targeted coal-fire power plants” when it strengthened existing regulations in 2024. Per a document reviewed by The New York Times, the EPA’s proposal will “loosen emissions limits for toxic substances such as lead, nickel, and arsenic by 67%,” and for mercury at some coal power plants by as much as 70%. “Reversing these protections will take lives, drive up costs, and worsen the climate crisis,” Climate Action Campaign Director Margie Alt said in a statement. “Instead of protecting American families, [President] Trump and [EPA Administrator Lee] Zeldin are turning their backs on science and the public to side with big polluters.”

Fervo Energy announced Wednesday morning that it has secured $206 million in financing for its 400-megawatt Cape Station geothermal project in southwest Utah. The bulk of the new funding, $100 million, comes from the Breakthrough Energy Catalyst program.

Fervo’s announcement follows on the heels of the company’s Tuesday announcement that it had drilled its hottest and deepest well yet — at 15,000 feet and 500 degrees Fahrenheit — in just 16 days. As my colleague Katie Brigham reports, Fervo’s progress represents “an all too rare phenomenon: A first-of-a-kind clean energy project that has remained on track to hit its deadlines while securing the trust of institutional investors, who are often wary of betting on novel infrastructure projects.” Read her full report on the clean energy startup’s news here.

The United Kingdom said Tuesday that it will move forward with plans to construct a $19 billion nuclear power station in southwest England. Sizewell C, planned for coastal Suffolk, is expected to create 10,000 jobs and power 6 million homes, The New York Times reports. Sizewell would be only the second nuclear power plant to be built in the UK in over two decades; the country generates approximately 14% of its total electricity supply through nuclear energy. Critics, however, have pointed unfavorably to the other nuclear plant under construction in the UK, Hinkley Point C, which has experienced multiple delays and escalating costs throughout its development. “For those who have followed Sizewell’s progress over the years, there was a glaring omission in the announcement,” one columnist wrote for The Guardian. “What will consumers pay for Sizewell’s electricity? Will it still be substantially cheaper in real terms than the juice that will be generated at Hinkley Point C in Somerset?” The UK additionally announced this week that it has chosen Rolls-Royce as the “preferred bidder” to build the country’s first three small modular nuclear reactors.

The European Union on Tuesday proposed a ban on transactions with Nord Stream 1 and 2 as part of a new package of sanctions aimed at Russia, Bloomberg reports. “We want peace for Ukraine,” the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, said at a news conference in Brussels. “Therefore, we are ramping up pressure on Russia, because strength is the only language that Russia will understand.” The package would also lower the price cap on Russian oil to $45 a barrel, down from $60 a barrel, von der Leyen said, as well as crack down on Moscow’s “shadow fleet” of vessels used to transport sanctioned products like crude oil. The EU’s 27 member states need to unanimously agree to the package for it to be adopted; their next meeting is on June 23.

The world’s oceans hit their second-highest temperature ever in May, according to the European Union’s Earth observation program Copernicus. The average sea surface temperature for the month was 20.79 degrees Celsius, just 0.14 degrees below May 2024’s record. Last year’s marine heat had been partly driven by El Niño in the Pacific, so the fact that the oceans remain warm in 2025 is alarming, Copernicus senior scientist Julien Nicolas told the Financial Times. “As sea surface temperatures rise, the ocean’s capacity to absorb carbon diminishes, potentially accelerating the build-up of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and intensifying future climate warming,” he said. In some areas around the UK and Ireland, the sea surface temperature is as high as 4 degrees Celsius above average.

The Pacific Island nation of Tonga is poised to become the first country to recognize whales as legal persons — including by appointing them (human) representatives in court. “The time has come to recognize whales not merely as resources but as sentient beings with inherent rights,” Tongan Princess Angelika Lātūfuipeka Tukuʻaho said in comments delivered ahead of the U.N. Ocean Conference in Nice, France.