You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

“Unbelievable. This looks like Baghdad or something.”

The shocked voice in the viral flyover video of Lahaina, Hawaii, belongs to helicopter tour pilot Richard Olsten, who attempted on Wednesday to find the words to describe the devastating transformation of the land below. Grass fires that burned on the fringes of the western Maui town early Tuesday, and were initially believed to be contained, have been fanned by powerful winds toward populated areas, fueling a fast-moving conflagration that took both residents and rescue workers by surprise.

Aerial video shows wildfire devastation in Lahaina, Mauiwww.youtube.com

The fires have killed at least 93 people, although authorities caution that the toll could rise as search-and-rescue efforts are ongoing. Here’s what you need to know about the Maui fires.

The cause of the fires is not known, although they appear to have originated as brush fires that did not draw much initial alarm. But high winds that NOAA and the National Weather Service attribute to Hurricane Dora, some 600 miles to the south, knocked out power on the island, grounded firefighting helicopters, and fanned deadly flare-ups that took residents by surprise.

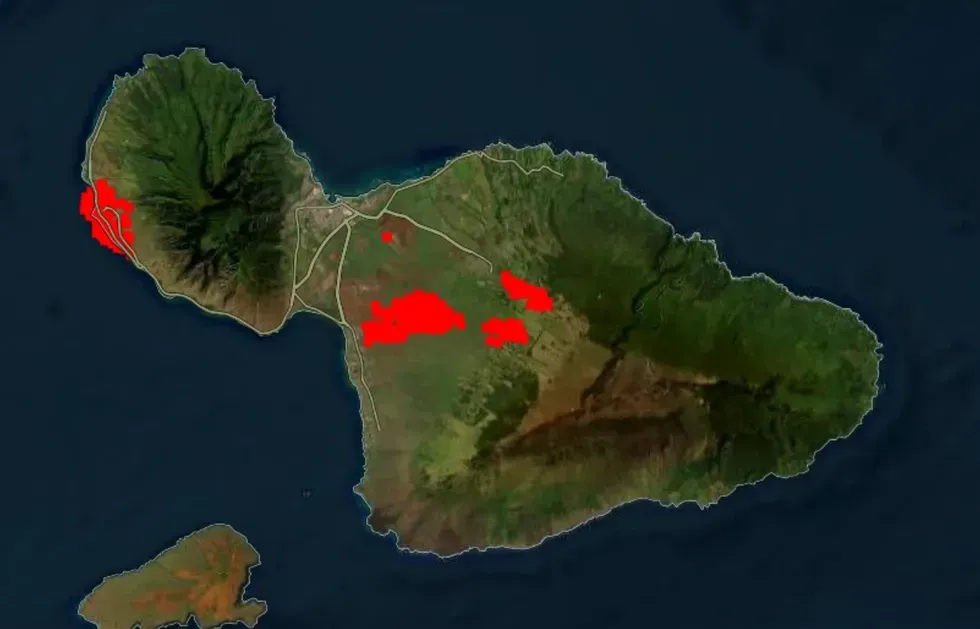

The location of the Maui fires.

NASA/FIRMS

The location of the fires as of August 10 at 12:30 PM ET are above. You can follow the location of the fires using NASA’s Fire Information for Resource Management System (FIRMS) here. There are also a number of small fires burning on Hawaii’s Big Island.

More than 271 structures have been impacted, according to the Maui County website, and “thousands” of acres have burned. More than 11,000 tourists have been evacuated from Maui and some 2,100 residents are reportedly being housed in emergency shelters.

“Local people have lost everything,” Jimmy Tokioka, the director of Hawaii’s Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism, told the press. “They’ve lost their house. They’ve lost their animals. It’s devastating.”

Lahaina, the former capital of the Kingdom of Hawaii and a place of historic and cultural importance to Native Hawaiians, has been “wiped off the map,” witnesses say. A 150-year-old banyan tree, thought to be the oldest in the state, has been scorched by the fire but appears to still be standing.

With 93 dead, the fires are one of the deadliest natural disasters in Hawaii’s recorded history and one of the deadliest modern U.S. wildfires. Authorities have warned that the death toll could rise.

As of Thursday, helicopters have resumed water drops and at least 100 Maui firefighters are working around the clock to stop the fire.

Horrifying. Survivors said they had little warning before the fire was upon them, with some being so taken by surprise that they had to jump into the ocean to escape the flames.

“While driving through the neighborhood, it looked like a war zone,” one Lahaina resident told USA Today of his escape. “Houses throughout that neighborhood were already on fire. I’m driving through the thickest black smoke, and I don’t know what’s on the other side or what’s in front of me.”

Another evacuee told Maui News she had no time to think through what to pack. “I grabbed some stuff, I put some clothes on, got some dog food. I have a giant tortoise. I couldn’t move him so I opened his gate so he could get out if he needed to,” she said.

“I was the last one off the dock when the firestorm came through the banyan tree and took everything with it,” another survivor recounted to the BBC. “And I just ran out to the beach and I ran south and I just helped everybody I could along the way.”

Hawaii’s brush fires tend to be smaller than the forest fires in the Western United States, but the proliferation of non-native vegetation, which dries out and is particularly fire-prone, has fueled a rise in recent blazes, The Washington Post reports.

There has been a 400% increase in wildfires “over the past several decades” in Hawaii, according to a 2022 report by Hawaii Business Magazine. “From 1904 through the 1980s, [University of Hawaii at Mānoa botanist and fire scientist Clay Trauernicht] estimates that 5,000 acres on average burned each year in Hawaii. In the decades that followed, that number jumped to 20,000 acres burned.”

Though Hawaii is imagined to be lush, wet, and tropical, Maui is experiencing moderate to severe drought, which has dried out the non-native grasses that make particularly good wildfire fuel. And while it is tricky to link Hawaii’s current drought directly to climate change, drought conditions in the Pacific Islands are expected to continue to increase along with warming.

Stronger hurricanes are also more likely due to climate change, and it was the strong winds buffeting Maui that made the fires this week so destructive and fast-moving. “These kinds of climate change-related disasters are really beyond the scope of things that we’re used to dealing with,” University of British Columbia researcher Kelsey Copes-Gerbitz told The Associated Press. “It’s these kind of multiple, interactive challenges that really lead to a disaster.”

The Hawaiʻi Tourism Authority has asked that “visitors who are on non-essential travel … leave Maui, and non-essential travel to Maui is strongly discouraged at this time.” If you have plans to travel to West Maui in the coming weeks, you are “encouraged to consider rescheduling [your] travel plans for a later time.”

This article was last updated on August 13 at 8:32 AM ET.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

CarbonPlan has a new tool to measure climate risk that comes with full transparency.

On a warming planet, knowing whether the home you’re about to invest your life savings in is at risk of being wiped out by a wildfire or drowned in a flood becomes paramount. And yet public data is almost nonexistent. While private companies offer property-level climate risk assessments — usually for a fee — it’s hard to know which to trust or how they should be used. Companies feed different datasets into their models and make different assumptions, and often don’t share all the details. The models have been shown to predict disparate outcomes for the same locations.

For a measure of the gap between where climate risk models are and where consumers want them to be, look no further than Zillow. The real estate website added a “climate risk” section to its property listings in 2024 in response to customer demand — only to axe the feature a year later at the behest of an industry group that questioned the accuracy of its risk ratings.

Now, however, a new tool that assesses wildfire risk for every building in the United States aims to advance the field through total transparency. The nonprofit research group CarbonPlan launched the free, user-friendly app called Open Climate Risk on Tuesday. It allows anyone to enter an address and view a wildfire risk score, on a scale of zero to 10, along with an explanation of how it was calculated. The underlying methodology, data, and code are all public. It’s the first fully open platform of its kind, according to CarbonPlan.

“Right now, the way science works in the climate risk space is that every model is independently developed at different companies, and we essentially have no idea what’s happening in them. We have no idea if they’re any good,” Oriana Chegwidden, a research scientist at CarbonPlan who led the creation of the tool, told me. “Our hope is that by opening this up, people will be able to start contributing, to help us learn how we can do it better.” That might mean critiquing CarbonPlan’s methods or code, for example, or re-running the model with additional data.

The score itself doesn’t tell you much other than the relative risk between one building and another. But the platform also breaks out the two inputs behind it: burn probability, or the likelihood a building will catch fire in a given year, and “conditional risk,” an estimate of how much of the building’s value would be lost if it does burn, based on projected fire intensity.

The projections are largely based on a U.S. Forest Service dataset that models fire frequency on wildlands throughout the country. CarbonPlan uses additional data on wind speed and direction to predict how a given fire might spread into an urban area.

Users can toggle between risk under the “current” climate and a “future” climate, which jumps about 20 years out. They can also see the distribution of buildings across the spectrum of risk scores at various geographic scales — by state, county, census tract, or census block.

One of CarbonPlan’s hopes is to help people become more informed consumers of climate risk data by helping them understand how it’s put together and what questions they might want to ask. While its model is more crude than others on the market, the tool is explicit about the factors that are not accounted for in the results. The loss estimates are based on a generic building, for example, and do not recognize specific traits like fire-resistant construction materials or landscaping that could make a home more fire resistant. They also don’t consider building-to-building spread. The underlying U.S. Forest Service data is also limited in that it maps vegetation across the country as it existed at the end of 2020 — any changes since then that could have reduced fire-igniting fuels, such as prescribed burns, are not incorporated.

Right now, there’s no industry standard for calculating or communicating climate risk. The Global Association of Risk Professionals recently asked 13 climate risk companies for data on floods, tropical storms, wildfires, and heat at 100 addresses to compare the outputs. The authors found there were “significant disparities,” between estimates of vulnerability and damages at the same locations. When it came to wildfires, specifically, they were unable to even compare the data, because the companies all conveyed the risk using different benchmarks.

The implications of having so many diverging methods and results extend beyond individual homebuying decisions. Insurance companies use climate risk data to set rates; publicly-traded companies use it to make disclosures to investors; policymakers use it to guide community planning and investments in adaptation. Some products might be better suited to one task or another.

Katherine Mach, an environmental science and policy professor at the University of Miami, told me the next step for the field is to have more systematic reporting requirements that help people understand how accurate the data are and what types of decisions they can be used for.

“It’s almost like we need the equivalent of industry standards,” she said. “You’re going to release a climate product? Here’s what you need to clearly communicate.”

CarbonPlan collected feedback from various likely users of the tool throughout the development process, including municipal planners, climate scientists, and consumer advocates. The group also hopes to foster an “iterative cycle of community-driven model development,” spurring other researchers to inspect the data, critique it, add to it, and spin out new versions. This is common practice in other areas of climate science, like Earth system modeling and economic modeling, and has been instrumental in advancing those fields. “There’s nothing like that for climate risk right now,” Chegwidden said.

The first step will be raising more money to support further work, but the goal is to partner with outside researchers on comparative analyses and case studies. Tracy Aquino Anderson, CarbonPlan’s interim executive director, told me they have already heard from one researcher who has a fire risk dataset that could be added to the platform. The group has also been invited to present the platform to two academic climate research groups later this spring.

The problem of black box models exists not just because the field is full of private companies that don’t want to share their code. A study published earlier this month found that only 4% of the most-cited peer-reviewed climate risk studies have made their data and code public, despite journal standards that require transparency.

“When you’re working with climate data, you’re dealing with all of these uncertainties,” Adam Pollack, an assistant professor at the University of Iowa who researches flood risk and the lead author of the paper, told me. “Researchers don’t always understand all of the assumptions that are implicit in choices that they make. That’s fine — we have methods for dealing with that. We do model intercomparisons, we do these synthesis studies as a field. The foundation of that is openness and reusability.”

Though he was not involved in the CarbonPlan project, he said it was exactly what his paper was calling for. For example, CarbonPlan’s “future” calculations are based on an extreme warming scenario that has become controversial among climate scientists. CarbonPlan didn’t choose this scenario — it’s what the Forest Service’s dataset used, and that was the only off-the-shelf data available for the entire United States. But because the underlying code is open-source, critics are free to swap it out for other data they may have access to.

“That’s what’s so great about this,” Pollack said. “People who have different values, assumptions, and expertise, can get new estimates and build a shared understanding.”

On BYD’s lawsuit, Fervo’s hottest well, and China’s geologic hydrogen

Current conditions: A midweek clipper storm is poised to bring as much as six more inches of snow to parts of the Great Lakes and Northeast • American Samoa is halfway through three days of fierce thunderstorms and temperatures above 80 degrees Fahrenheit • Northern Portugal is bracing for up to four inches more of rain after three deadly storms in just two weeks.

The Environmental Protection Agency is preparing this week to repeal the Obama-era scientific finding that provides the legal basis for virtually all federal regulations of planet-heating emissions, marking what The Wall Street Journal called “the most far-reaching rollback of U.S. climate policy to date.” The 2009 “endangerment finding” concluded that greenhouse gases pose a threat to public health and welfare, calling for cuts to emissions from power plants and vehicle tailpipes. EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin told the newspaper the move “amounts to the largest act of deregulation in the history of the United States.” In an interview with my colleague Emily Pontecorvo last year, Harvard Law School’s Jody Freeman said rescinding the endangerment finding would do “more serious and more long term damage” and “could knock out a future administration from trying to” bring back climate policy. But that, Freeman said, would depend on the Supreme Court backing the administration. “I don’t think that’s likely, but it’s possible,” she said.

At issue is the 2007 case Massachusetts v. EPA, which determined that greenhouse gases qualified as pollutants under the Clean Air Act. As Emily wrote last week, “the agency claims that its previous read of Massachusetts v. EPA was wrong, especially in light of subsequent Supreme Court decisions, such as West Virginia v. EPA and Loper Bright v. Raimondo. The former limited the EPA's toolbox for regulating power plants, and the latter ended a requirement that courts defer to agency expertise in cases where the law is vague.” An earlier report in The Washington Post questioned whether the agency would proceed with the repeal at all, fearing these arguments would pass muster in the nation’s highest court.

BYD has sued the United States government over the 100% tariff on Chinese electrics that serves as an effective ban on Beijing’s booming auto exports. Four U.S.-based subsidiaries of the world’s largest manufacturer of electric vehicles filed a lawsuit in the U.S. Court of International Trade challenging the legality of the Trump administration’s trade levies. The litigation marks what the state-backed tabloid Global Times called “the first instance of a Chinese automaker directly and actively challenging U.S. tariffs, setting a precedent and carrying significance for Chinese enterprises to protect their legitimate rights and interests through legal means.”

Outside the U.S., BYD is booming. China’s cheap electric cars are popular all over the world, as Heatmap’s Shift Key podcast covered in December. Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney’s deal to increase trade with China will bring the battery-powered vehicles to North American roads. And the Chinese edition of the trade publication Automotive News just reported that BYD is planning a factory expansion in Europe and Canada.

Hot off last month’s news that it plans to go public, Fervo Energy has drilled its highest-temperature well yet. The drilling results confirm that the next-generation geothermal startup tapped into a resource with temperatures above 555 degrees Fahrenheit at approximately 11,200 feet deep. The company announced the findings Monday of an independent assessment using appraisal data from the drilling. The analysis found that the Project Blanford site in Millard County, Utah, has multiple gigawatts of heat that can be harnessed. Its completion will be a breakthrough for enhanced geothermal systems, one of two leading approaches to the next-generation geothermal sector that Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin outlined here. “This latest ultra-high temperature discovery highlights our team’s ability to detect and develop EGS sweet spots using AI-enhanced geophysical techniques,” Jack Norbeck, Fervo’s co-founder and chief technology officer, said in a statement.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

Chinese scientists have for the first time discovered natural hydrogen sealed in microscopic inclusions near Tibet. The finding, which the Xinhua news agency called “groundbreaking,” fills what the China Hydrogen Bulletin called “a major domestic research gap and points to a new geological pathway for identifying China’s next generation of clean energy resources.” Natural, or geological, hydrogen could provide a cheap source of the zero-carbon fuel and give oil and gas drillers a natural foothold in a new, clean industry. In the color spectrum associated with hydrogen, the rare, naturally formed stuff is called white hydrogen. But as Heatmap’s Katie Brigham wrote in December, a new color has joined the rainbow. Orange hydrogen refers to a family of technologies that naturally spur production of the gas, as the startup Vema is now attempting to do.

China’s coal-fired power generation decreased 1.9% last year, marking what the consultancy Wood Mackenzie called “a historic shift driven by new non-fossil generation that has finally outpaced demand growth.” Power demand surged 5% in China last year, but for the first time in a decade that wasn’t propelled by coal plants. Instead, that new demand was supplied by renewables, nuclear, and hydro, all of which Beijing has rapidly deployed. Over that time, the levelized cost of energy — a widely used though, as Matthew wrote last year, far-from-perfect metric — fell 77% for utility-scale solar and 73% for onshore wind. “At the heart of this transformation is the unprecedented expansion of renewable energy capacity,” Sharon Feng, a senior research analyst for Wood Mackenzie, said in a statement. “China’s wind and solar capacity had risen more than ten-fold to 1,842 gigawatts over the past decade.”

Gone are the days when the oil industry seemed to be on track for a lucrative decline. Demand for crude will take longer to peak than previously estimated as governments prioritize growth and energy security over efforts to curb consumption. That’s according to a report issued Sunday by Vitol Group, the world’s largest independent oil trader. “Over the past year, decarbonisation policies have become a less decisive driver of efforts to curb oil consumption and reduce carbon dioxide emissions,” the report stated, according to Bloomberg. “Policy priorities have increasingly been reframed around economic competitiveness and geopolitical strategy.”

The race for a long-duration energy storage solution has a new competitor. The Dutch startup Ore Energy has deployed its iron-air storage technology successfully on the grid for a technical pilot of its system that can store for 100 hours of power. The pilot, the first of its kind in Europe, demonstrated that the company’s technology can store and discharge energy for up to four days. “This pilot allowed us to evaluate iron-air performance under European operating profiles and real-world grid conditions,” Aytaç Yilmaz, co-founder and CEO of Ore Energy, said in a statement.

Wildfires are moving east.

There were 77,850 wildfires in the United States in 2025, and nearly half of those — 49% — ignited east of the Mississippi River, according to statistics released last week by the National Interagency Fire Center. That might come as a surprise to some in the West, who tend to believe they hold the monopoly on conflagrations (along with earthquakes, tsunamis, and megalomaniac tech billionaires).

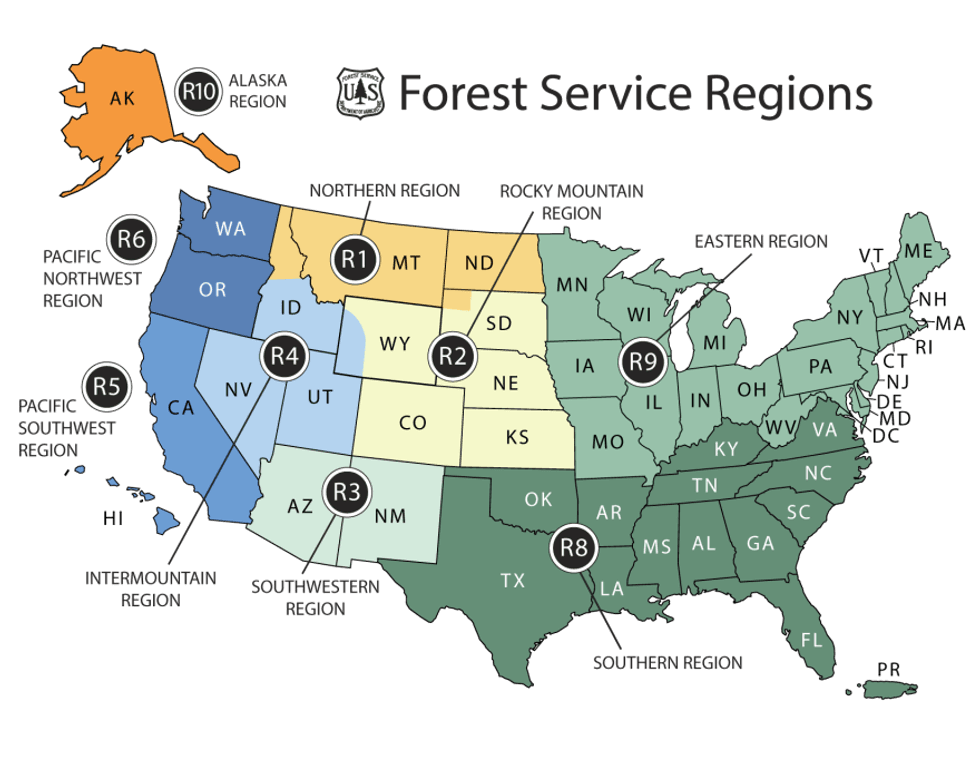

But if you lump the Central Plains and Midwest states of Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas along with everything to their east — the swath of the nation collectively designated as the Eastern and Southern Regions by the U.S. Forest Service — the wildfires in the area made up more than two-thirds of total ignitions last year.

Like fires in the West, wildfires in the eastern and southeastern U.S. are increasing. Over the past 40 years, the region has seen a 10-fold jump in the frequency of large burns. (Many risk factors contribute to wildfires, including but not limited to climate change.)

What’s exciting to wildfire researchers and managers, though, is the idea that they could catch changes to the Eastern fire regime early, before the situation spirals into a feedback loop or results in a major tragedy. “We have the opportunity to get ahead of the wildfire problem in the East and to learn some of the lessons that we see in the West,” Donovan said.

Now that effort has an organizing body: the Eastern Fire Network. Headed by Erica Smithwick, a professor in Penn State’s geography department, the research group formed late last year with the help of a $1.7 million, three-year grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, a partner with the U.S. National Science Foundation, with the goal of creating an informed research agenda for studying fire in the East. “It was a very easy thing to have people buy into because the research questions are still wide open here,” Smithwick told me.

Though the Eastern U.S. is finally exiting a three-week block of sub-freezing temperatures, the hot, dry days of summer are still far from most people’s minds. But the wildland-urban interface — that is, the high-fire-risk communities that abut tracts of undeveloped land — is more extensive in the East than in the West, with up to 72% of the land in some states qualifying as WUI. The region is also much more densely populated, meaning practically every wildfire that ignites has the potential to threaten human property and life.

It’s this density combined with the prevalent WUI that most significantly distinguishes Eastern fires from those in the comparatively rural West. One fire manager warned Smithwick that a worst-case-scenario wildfire could run across the entirety of New Jersey, the most populous state in the nation, in just 48 hours.

Generally speaking, though, wildfires in the East are much smaller than those in the West. The last megafire in the Forest Service’s Southern Region was as far west in its boundaries as you can get: the 2024 Smokehouse Creek fire in Texas and Oklahoma, which burned more than a million acres. The Eastern Region hasn’t had a megafire exceeding 100,000 acres in the modern era. For research purposes, a “large” wildfire in the East is typically defined as being 200 hectares or more in size, the equivalent of about 280 football fields; in the West, a “large” wildfire is twice that, 400 hectares or more.

But what the eastern half of the country lacks in total acres burned (for that statistic, Alaska edges out the Southern Region), it makes up for in the total number of reported ignitions. In 2025, for example, the state of Maine alone recorded 250 fires in August, more than doubling its previous record of just over 100 fires. “The East is highly fragmented,” Donovan, who is contributing to the Eastern Fire Network’s research, told me. “We have a lot of development here compared to the West, and so it’s much more challenging for fires to spread.”

Fires in the West tend to be long-duration events, burning for weeks or even months; fires in the East are often contained within 48 hours. In New Jersey, for example, “smaller, fragmented forests, which are broken up by numerous roads and the built environment, [allow] firefighters to move ahead of a wildfire to improve firebreaks and begin backfiring operations to help slow the forward progression,” a spokesperson for the New Jersey Forest Fire Service told me.

The parcelized nature of the eastern states is also reflected in who is responding to the fires. It is more common for state agencies and local departments — including many volunteer firefighting departments — to be the ones on the scene, Debbie Miley, the executive director of the National Wildfire Suppression Association, a trade group representing private wildland fire service contractors, told me by email. On the one hand, the local response makes sense; smaller fires require smaller teams to fight them. But the lack of a joint effort, even within a single state, means broader takeaways about mitigation and adaptation can be lost.

“Many eastern states have strong state forestry agencies and local departments that handle wildfire as part of an ‘all hazards’ portfolio,” Miley said. “In the West, there’s often a deeper bench of personnel and systems oriented around long-duration wildfire campaigns (though that varies by state).”

All of this feeds into why Smithwick believes the Eastern Fire Network is necessary: because of this “intermingling, at a very fine scale, of different jurisdictional boundaries,” conversations about fire management and the changing regimes in the region happen in parallel, rather than with meaningful coordination. Even within a single state, fire management might be divided between different agencies — such as the Game Commission and the Bureau of Forestry, which share fire management responsibilities in Pennsylvania. Fighting fires also often involves working with private landowners in the East; in the West, on the other hand, roughly two-thirds of wildfires burn on public land, which a single agency — e.g. the Bureau of Land Management, Forest Service, or Park Service — manages.

But “wildfire risk is going to be different than in the West, and maybe more variable,” Smithwick told me. Identifying the appropriate research questions about that risk is one of the most important objectives of the Eastern Fire Network.

Bad wildfires are the result of fuel and weather conditions aligning. “We generally know what the fuels are [in the East] and how well they burn,” Smithwick said. But weather conditions and their variability are a greater question mark.

Nationally, fire and emergency managers rely on indices to predict fire-weather risk based on humidity, temperature, and wind. But while those indices are dialed in for the Western states, they’re less well understood in the East. “We hope to look at case studies of recent fires that have occurred in the 2024 and 2025 window to look at the antecedent conditions and to use those as case studies for better understanding the mechanisms that led to that wildfire,” Smithwick said.

Learning more about the climatological mechanisms driving dry spells in the region is another explicit goal. Knowing how dry spells evolve, and where, will help researchers and eventually policymakers to identify mitigation strategies for locations most at risk. Smithwick also expects to learn that some areas might not be at high risk: “We can tell you that this is not something your community needs to invest in right now,” she told me.

Different management practices, jurisdictions, terrains, and fuel types mean solutions in the East will look different from those in the West, too. As Donovan’s research has found, the unmanaged regrowth of forests in the northeast in particular after centuries of deforestation has led to an increase in trees and shrubs that are prone to wildfires. Due to the smaller forest tracts in the area, mechanical thinning is a more realistic solution in eastern forests than on large, sprawling, remote western lands.

Prescribed burns tend to be more common and more readily accepted practices in the East, too. Florida leads the nation in preventative fires, and the New Jersey Forest Fire Service aims to treat 25,000 acres of forest, grasslands, and marshlands with prescribed fire annually.

The winter storms that swept across the Eastern and Southern regions of the United States last month have the potential to queue up a bad fire season once the land starts to thaw and eventually dry out. Though the picture in the Eastern Region is still coming into focus depending on what happens this spring, in the Southern region the storms have created “potential compaction of the abundant grasses across the Plains, in addition to ice damage in pine-dominant areas farther east,” the National Interagency Fire Center wrote in last Monday’s update to its nationwide fire outlook. (The nearly million-acre Pinelands of New Jersey are similarly a fire-adapted ecosystem and are “comparable in volatility to the chaparral shrublands found in California and southern Oregon,” the spokesperson told me.)

The compaction of grasses is significant because, although they will take longer to dry and become a fuel source, it will ultimately leave the Southern region covered with a dense, flammable fuel when summer is in full swing. Beyond the Plains, in the Southeast’s pine forests, the winter-damaged trees could cast “abundant” pine needles and “other fine debris” that could dry out and become flammable as soon as a few weeks from now. “Increased debris burning will also amplify ignitions and potential escapes, enhancing significant fire potential during warmer and drier weather that will return in short order,” NIFC goes on to warn.

Though the historically wet Northeast and humid Southeast seem like unlikely places to worry about large wildfires, as conditions change, nothing is certain. “If we learned anything from fire science over the past few decades, it’s that anywhere can burn under the right conditions,” Smithwick said. “We are burning in the tundra; we are burning in Canada; we are burning in all of these places that may not have been used to extreme wildfire situations.”

“These fires could have a large economic and social cost,” Smithwick added, “and we have not prepared for them.”