You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

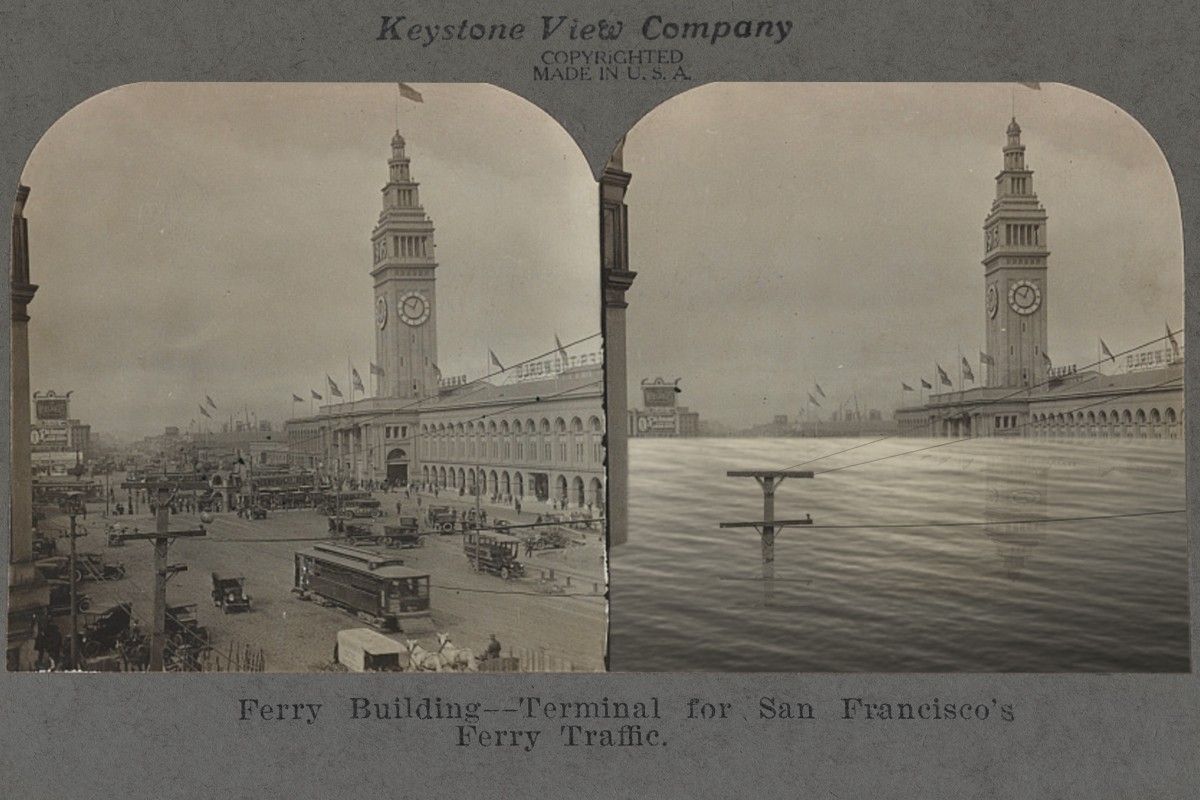

The effort to preserve the beloved landmark from sea-level rise epitomizes an existential struggle for historic waterfronts

When San Francisco’s Ferry Plaza Farmers Market is in full Saturday swing, one way to dodge the determined foodies and casual browsers is to retreat to the plaza just 30 steps south of the Ferry Building. It sits atop three tiers of dark-veined granite, accessible by two flights of nine stairs or a ramp that ascends along the water to a trio of ferry gates that, like the plaza, were completed in 2021.

The chosen height hints at what someday might be the norm — the elevation where San Francisco’s constructed shoreline will need to be to serve as a protective buffer between the natural bay and the developed city. Here, more than any place on today’s Embarcadero, you confront the existential predicament facing the Ferry Building, nearby piers, and resurrected waterfronts in other coastal American cities: sea level rise.

According to projections that were modeled by climate scientists in 2018, San Francisco Bay faces a 66% likelihood that average daily tides will rise 40 inches by 2100, with roughly half of the increase during the next 50 years and the pace accelerating after that. The same report includes an extreme but peer-reviewed scenario where the projected increase soars to 93 inches during that same period — making grim numbers profoundly worse.

So-called king tides already arrive monthly during the winter, a natural occurrence related to the moon’s gravitational pull that can send waves washing past Pier 14 into the Embarcadero’s protected bike lane. Behind Pier 5, water swells up and over the edge of the public walkway. For now, that occasional splash of excitement is less fearsome than fun — but if current forecasts are anywhere near accurate, future generations will face a double bind.

The threat isn’t just that tides might creep upward as temperatures increase. It’s that the extreme rainfall patterns we already experience will grow more intense, those destructive storms that in recent years have introduced terms like atmospheric rivers and bomb cyclones into conversations about the weather. For instance, if daily tides are a foot higher in 2050 than they are now — the “likely” projection — a major storm could surge 36 inches beyond where it would register today.

In the case of the Embarcadero, the hypothetical one-foot rise coupled with an “intense storm” — the sort that in the past might occur every five years — would send bay waters rushing toward the roadway in a dozen locations if the storm hit when winds were brisk and the tide was high. Kick the downpour’s fervor to the scale of the bomb cyclone that hit the Bay Area in October 2021 — a day-long deluge that was the equivalent of what scientists call a 25-year storm — and the Embarcadero could be closed for nearly a mile between Folsom Street and Pier 9. Water spilling across the roadway could flow down into the BART and Muni subway beneath Market Street, potentially paralyzing both systems.

The new plaza and the elevated ferry gates might rebuke the surging tides to come, but the landmark next door would be more vulnerable than ever. The Ferry Building has ridden out many perils since opening day in 1898, from earthquakes and the onslaught of automobiles to political tumult, misguided renovations, and the wear and tear of urban life. Now it faces the implacable though seemingly far-off threat of rising waters, as if nature was determined to restore the marshes and tidal flats that long-dead San Franciscans covered and forgot.

The addition of the granite plaza is an indicator of the danger facing the icon to its north. And it’s not as if our hefty landmark with that vaulted concrete foundation can be jacked up out of harm’s way.

Or can it?

Steven Reel headed west from Philadelphia in 1992 to earn a structural engineering degree at Stanford University because, he says now, “structural engineering means ‘earthquakes’ at Stanford, and earthquakes make structural engineering a lot more interesting.” The Bay Area was a good place to live, and local governments were investing heavily in seismic upgrades after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. In 2010, Reel successfully applied for a job at the Port of San Francisco and, to his surprise, grew intrigued by the historic aspects of making an urban shoreline function in the here and now.

“I’d start studying old engineering drawings for projects and then go down the rabbit hole,” recalls Reel, an easygoing bureaucrat with a beard that approached Rasputin-like proportions during the pandemic (he since has trimmed it back). He also began to notice regional planners stressing sea level rise in meetings.

His first project at the port was Brannan Street Wharf, where two ramshackle piers midway between the Bay Bridge and the ballpark were torn out and replaced by a four-hundred-foot-long triangular green. The response to climate concerns involved a slight upward incline from the Embarcadero promenade and a concrete lip along the edge (the same move since used for the plaza near the Ferry Building).

There was another natural threat to consider — the possibility that a tremor on the scale of the Great 1906 San Francisco Earthquake could strike again. Would the Ferry Building and the seawall hold, as before? Or would the three-mile-long agglomeration of boulders and concrete give way after all this time? Reel found himself with a new job title — manager of the seawall program — and responsibilities that included a $450,000 study with consultants being told to diagnose the barrier’s health and prescribe possible remedies.

The findings, released in April 2016, answered some questions and posed a host of others.

The good news is that even with a cataclysmic earthquake, “complete failure of the seawall is unlikely.” The rocks and boulders that form a dike beneath the concrete wouldn’t scatter like marbles. The Financial District wouldn’t be sucked into the bay toward Oakland. But the combination of sandy fill atop soft mud, behind an aged barrier with thousands of potentially moving parts of varying size, is a dangerous combination. The fill was “subject to liquefaction,” the report confirmed, making it likely that the seawall could slump and lurch outward.

“A repeat of the 1906 earthquake is predicted to cause as much as $1b in damage and $1.3b in disruption costs,” the report declared. Better to strengthen the entire three-mile seawall before a disaster struck — though the cost estimates to do this were “on the order of $2 to $3 billion.” The consultants also emphasized that even with an upgraded seawall, the slow-moving threat posed by sea level rise “will necessitate intervention ... over the next 100 years.” Figure that in, and the combined price tag approached $5 billion.

The city approached voters with a $425 million bond in 2018 to fund the first round of projects; smartly, the campaign emphasized seismic concerns, lightening the ominous message with such creative touches as a neighborhood brewpub’s limited-release sour beer dubbed “Seawall’s Sea Puppy.” The bond passed with 83% support. “The earthquake message resonates,” Reel says. “Without it, I don’t think all this would have moved forward as it did.”

It makes sense to tackle the easiest fixes early, given the seismic threats posed to the Bay Area by the San Andreas and other faults. Breaking a daunting future into manageable parts also allows the Port and City Hall to shift attention from the more eye-popping aspects of climate adaptation — such as how potions of the Embarcadero might need to be raised as much as seven feet to prepare for 2100’s more extreme projected water levels.

Which leads us back to the Ferry Building.

As so often has been the case during the landmark’s history, far more is at stake than one particular structure. If the Ferry Building in its heyday represented San Francisco’s prominence within the region and beyond, in the 21st century it embodies how urban waterfronts can be reinvented without sacrificing their past identities. At the same time, the building remains essentially the same as it was in 1898 — a heavy structure of concrete and steel that covers two acres and rises from a foundation atop bundled piles of tree trunks.

The assumption for the past 25 years has been that the landmark’s impressive performance in 1906 and 1989 should ensure similar resilience when the next big earthquake hits. But the most recent geotechnical exam revealed a weak link: the section of the seawall behind the Ferry Building rests in a trench filled with liquefiable sand rather than the rubble that underlies almost everything else. That detail places “the 125-year-old Ferry Building Seawall, building substructure, and surrounding piers at risk of damage in large earthquakes,” according to the most recent Port update.

This isn’t just a concern for architecture buffs. San Francisco’s disaster relief plans treat the outdoor spaces around the landmark as crucial spots for retreat and regrouping. In a worst-case scenario where the Bay Bridge is knocked out of commission, as was the case in 1989, reliable access to a functioning ferry system will be crucial for evacuating people from the downtown scene safely. The new plaza can also serve as a staging area for bringing medical aid and supplies into the city over the water. Regular people who need to connect with family and friends know there won’t be confusion if someone says “let’s find each other at the Ferry Building.”

One solution could be to erect an entirely new seawall around the edge of the Ferry Building’s foundation, in essence creating a basement beneath it. And if you’re doing that, it’s only one more step — albeit sure to be costly and complex — to raise the entire building by several feet and resolve the challenge of sea level rise for another lifetime or two.

“With the Ferry Building, the one thing I know about it is that it has to be saved … it has such a strong identification with the city,” Elaine Forbes, the executive director for the Port, says. “So I talked myself into okaying this big expenditure.”

Realistically, adaptation planning in San Francisco and other waterfront cities will involve a variety of responses at a variety of scales. But the situation facing the Ferry Building, as at so many times in its history, is unique unto itself. This time around, the task is to remake a bustling civic icon so that life seemingly goes on as before. If anyone has challenged the need to invest what likely will be hundreds of millions of dollars to save a 125-year-old structure, the argument has gained no traction.

“The price would have to be really, really high before anything would think twice” about whether the Ferry Building’s salvation is more trouble than it’s worth, Reel says. He describes how during the public discussions on what to do about the Embarcadero, attendees would be asked to list priorities. What are you concerned about? What do you love?

In the latter category, Reel recalls, “the Ferry Building kept getting named. People want to see it forever.”

This still leaves an array of unanswered questions. How to decide how big of an engineering gamble to take. Whether to raise the structure, as implausible as that sounds, or build a new seawall to the east that would destroy the immediacy of the connection to the water. And what becomes of the tenants inside the building, especially the locally based merchants, if the building once again becomes a construction zone.

In a much different context, one San Franciscan offered a fatalistic take on what the future might hold: Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

Four years before his death in 2021, still living in North Beach, Ferlinghetti sat down in a neighborhood café to talk with a Washington Post writer about the beat era, the 97-year-old poet’s life, and his enduring love for the city that he embraced long ago. At one point, the writer asked Ferlinghetti about what might happen after he was gone.

“It’s all going to be underwater in 100 years or maybe even 50,” Ferlinghetti said with a half-smiled shrug. “The Embarcadero is one of the greatest esplanades in the world. On the weekends, thousands of people strut up and down like it’s the Ramblas in Barcelona. But it’ll all be underwater.”

This article was excerpted and condensed from John King’s book Portal: San Francisco’s Ferry Building and the Reinvention of American Cities, available on Nov. 7 from W. W. Norton & Company ©2023.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

On Heatmap's annual survey, Trump’s wind ‘spillover,’ and Microsoft’s soil deal

Current conditions: A polar vortex is sweeping frigid air back into the Northeast and bringing up to 6 inches of snow to northern parts of New England • Temperatures in the Southeast are set to plunge 25 degrees Fahrenheit below last week’s averages, with highs below freezing in Atlanta • Temperatures in the Nigerian capital of Abuja, meanwhile, are nearing 100 degrees.

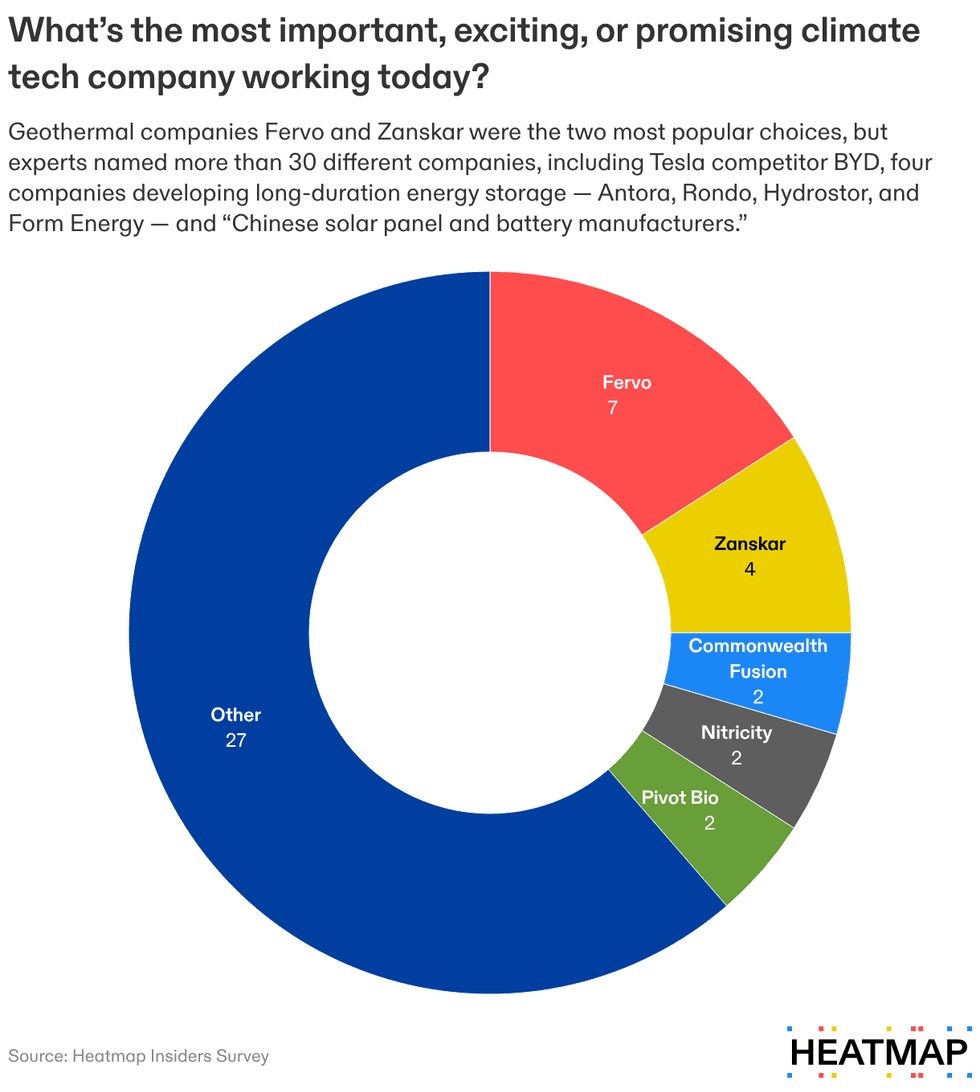

To comically understate the obvious, it’s been a big year for climate. So Heatmap called up 55 of the most discerning and disputatious experts — scientists, researchers, innovators, and reformers; some of whom led the Biden administration’s policy efforts, some of whom are harsh or heterodox critics of mainstream environmentalism. We asked them to take stock of everything going on now, from the Trump administration’s shifting policy landscape to China’s evolving place in the world.

The results of that inquiry are now out. You can check out everything on this homepage.

Or see:

Wyoming is inching closer to building what could be the United States’ largest data center after commissioners in Laramie County last week unanimously approved construction of a complex designed to scale from an initial 1.8 gigawatts to 10 gigawatts. The facility, called Project Jade, is set to be built by the data center giant Crusoe, with the neighboring gas turbines to power the plant provided by BFC Power and Cheyenne Power Hub. Crusoe’s chief real estate officer, Matt Field, told commissioners last week that the first phase would “leverage natural gas with a potential pathway for CO2 sequestration in the future” by tapping into developer Tallgrass Energy Partners’ existing carbon well hub, Inside Climate News wrote Wednesday.

While the potential for renewables is under discussion, a separate state hearing last week highlighted mounting opposition to the most prolific source of clean power in the state: Wind energy. Nearly two dozen residents from central and southeast Wyoming lambasted a growing “wall” of wind turbines in what Wyofile described as “emotional pleas.” One Cheyenne resident named Wendy Volk said: “This is no longer a series of isolated projects. It is a continuous, or near continuous, industrial corridor stretching across multiple counties and landscapes.”

Global wind executives are warning of “negative spillover” effects on investor sentiment from the Trump administration’s suspended leases on all large U.S. offshore wind projects. In an interview with the Financial Times, Vestas CEO Henrik Andersen, who also serves as the president of the industry group WindEurope, called 2025 a “rollercaster” year. “When you have a 20- to 30-year investment program, the only way you can cover yourself for risk is to ask for a higher return,” he said. “When you get impairments in an industry, everyone would start saying, ‘could that hit us as well?’”

The British government seems willing to reduce that risk. On Wednesday, the United Kingdom handed out record subsidy contracts for offshore wind projects. At the same time, however, oil giant BP wrote down the value of its low-carbon business — which includes wind, solar, and hydrogen — by upward of $5 billion, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

Microsoft on Thursday announced one of the largest soil-based deals to remove carbon from the atmosphere. Under a 12-year agreement, the tech giant will purchase 2.85 million credits from the startup Indigo Carbon PBC, which sequesters carbon dioxide in soil through regenerative agricultural practices. It’s the third deal between Indigo and Microsoft, building on 40,000 metric tons in 2024 and 60,000 last year. “Microsoft is pleased by Indigo’s approach to regenerative agriculture that delivers measurable results through verified credits and payments to growers, while advancing soil carbon science with advanced modeling and academic partnerships,” Phillip Goodman, Microsoft’s director of carbon removal, said in a statement. Microsoft, as my colleague Emily Pontecorvo wrote recently, has “dominated” carbon removal over the past year, increasing its purchases more than fivefold in 2025 compared to 2024.

Despite major progress on clean energy, especially with solar and batteries, a new report by McKinsey & Company found big gaps between current deployments and 2030 goals. The analysis, the first from the megaconsultancy to include China and nuclear power, highlighted “notable discrepancies between announced projects and those with committed funding,” and warned that less than “15% of low-emissions technologies required to meet Paris-aligned goals have been deployed.” In a statement, Diego Hernandez Diaz, McKinsey partner and co-author of the report, said the “progress landscape is nuanced by region and technology and while achieving energy transition commitments remain paramount for countries and companies alike, recent announcements indicate that shifting priorities and slowing momentum have led to project pauses and cancellations across technologies.”

The findings come as emissions are rising. As I wrote in yesterday’s newsletter, the latest Rhodium Group estimate of U.S. emissions notched a reversal of the last two years of declines. In a new Carbon Brief analysis, climate scientist Zeke Hausfather found that 2025 was in the top-three warmest years on record with average surface temperatures reaching 1.44 Celsius above pre-industrial averages across eight independent datasets.

China just installed the most powerful turbine ever built offshore. The 20-megawatt turbine off the coast of Fujian Province set a record for both capacity and rotor diameter, 300 meters from its 147-meter blades. “Compared with offshore wind farms with 16-megawatt units, 20-megawatt units can help wind farms reduce the number of units by 25%, save sea area, dilute development costs, and open up economic blockages for the large-scale development of deep-sea wind power,” the manufacturer, Goldwind, said in a statement.

Rob takes Jesse through our battery of questions.

Every year, Heatmap asks dozens of climate scientists, officials, and business leaders the same set of questions. It’s an act of temperature-taking we call our Insiders Survey — and our 2026 edition is live now.

In this week’s Shift Key episode, Rob puts Jesse through the survey wringer. What is the most exciting climate tech company? Are data centers slowing down decarbonization? And will a country attempt the global deployment of solar radiation management within the next decade? It’s a fun one! Shift Key is hosted by Robinson Meyer, the founding executive editor of Heatmap, and Jesse Jenkins, a professor of energy systems engineering at Princeton University.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Here is an excerpt from our conversation:

Robinson Meyer: Next question — you have to pick one, and then you’ll get a free response section. Do you think AI and data centers energy needs are significantly slowing down decarbonization, yes or no?

Jesse Jenkins: Significantly. Yeah, I guess significantly would … yes, I think so. I think in general, the challenge we have with decarbonization is we have to add new, clean supplies of energy faster than demand growth. And so, in order to make progress on existing emissions, you have to exceed the demand growth, meet all of that growth with clean resources, and then start to drive down emissions.

If you look at what we’ve talked about — are China’s emissions peaking, or global emissions peaking? I mean, that really is a game. It’s a race between how fast we can add clean supply and how fast demand for energy’s growing. And so in the power sector in particular, an area where we’ve made the most progress in recent years in cutting emissions, now having a large, and rapid growth in electricity demand for a whole new sector of the economy — and one that doesn’t directly contribute to decarbonization, like, say, in contrast to electric vehicles or electrifying heating —certainly makes things harder. It just makes that you have to run that race even faster.

I would say in the U.S. context in particular, in a combination of the Trump policy environment, we are not keeping pace, right? We are not going to be able to both meet the large demand growth and eat into the substantial remaining emissions that we have from coal and gas in our power sector. And in particular, I think we’re going to see a lot more coal generation over the next decade than we would’ve otherwise without both AI and without the repeal of the Biden-era EPA regulations, which were going to really drive the entire coal fleet into a moment of truth, right? Are they gonna retrofit for carbon capture? Are they going to retire? Was basically their option, by 2035.

And so without that, we still have on the order of 150 gigawatts of coal-fired power plants in the United States, and many of those were on the way out, and I think they’re getting a second lease on life because of the fact that demand for energy and particularly capacity are growing so rapidly that a lot of them are now saying, Hey, you know what, we can actually make quite a bit of money if we stick around for another 5, 10, 15 years. So yeah, I’d say that’s significantly harder.

That isn’t an indictment to say we shouldn’t do AI. It’s happening. It’s valuable, and we need to meet as much, if not all of that growth with clean energy. But then we still have to try to go faster, and that’s the key.

Mentioned:

This year’s Heatmap Insiders Survey

Last year’s Heatmap Insiders Survey

The best PDF Jesse read this year: Flexible Data Centers: A Faster, More Affordable Path to Power

The best PDF Rob read this year: George Marshall’s Guide to Merleau-Ponty's Phenomenology of Perception

This episode of Shift Key is sponsored by …

Heatmap Pro brings all of our research, reporting, and insights down to the local level. The software platform tracks all local opposition to clean energy and data centers, forecasts community sentiment, and guides data-driven engagement campaigns. Book a demo today to see the premier intelligence platform for project permitting and community engagement.

Music for Shift Key is by Adam Kromelow.

They still want to decarbonize, but they’re over the jargon.

Where does the fight to decarbonize the global economy go from here? The past 12 months, after all, have been bleak. Donald Trump has pulled the United States out of the Paris Agreement (again) and is trying to leave a precursor United Nations climate treaty, as well. He ripped out half the Inflation Reduction Act, sidetracked the Environmental Protection Administration, and rechristened the Energy Department’s in-house bank in the name of “energy dominance.” Even nonpartisan weather research — like that conducted by the National Center for Atmospheric Research — is getting shut down by Trump’s ideologues. And in the days before we went to press, Trump invaded Venezuela with the explicit goal (he claims) of taking its oil.

Abroad, the picture hardly seems rosier. China’s new climate pledge struck many observers as underwhelming. Mark Carney, who once led the effort to decarbonize global finance, won Canada’s premiership after promising to lift parts of that country’s carbon tax — then struck a “grand bargain” with fossiliferous Alberta. Even Europe seems to dither between its climate goals, its economic security, and the need for faster growth.

Now would be a good time, we thought, for an industry-wide check-in. So we called up 55 of the most discerning and often disputatious voices in climate and clean energy — the scientists, researchers, innovators, and reformers who are already shaping our climate future. Some of them led the Biden administration’s climate policy from within the White House; others are harsh or heterodox critics of mainstream environmentalism. And a few more are on the front lines right now, tasked with responding to Trump’s policies from the halls of Congress — or the ivory minarets of academia.

We asked them all the same questions, including: Which key decarbonization technology is not ready for primetime? Who in the Trump administration has been the worst for decarbonization? And how hot is the planet set to get in 2100, really? (Among other queries.) Their answers — as summarized and tabulated by my colleagues — are available in these pages.

You can see whether insiders think data centers are slowing down decarbonization and what folks have learned (or, at least, say they’ve learned) from the repeal of clean energy tax credits in the Inflation Reduction Act.

But from many different respondents, a mood emerged: a kind of exhaustion with “climate” as the right frame through which to understand the fractious mixture of electrification, pollution reduction, clean energy development, and other goals that people who care about climate change actually pursue. When we asked what piece of climate jargon people would most like to ban, we expected most answers to dwell on the various colors of hydrogen (green, blue, orange, chartreuse), perhaps, or the alphabet soup of acronyms around carbon removal (CDR, DAC, CCS, CCUS, MRV). Instead, we got:

“‘Climate.’ Literally the word climate, I would just get rid of it completely,” one venture capitalist told us. “I would love to see people not use 'climate change' as a predominant way to talk to people about a global challenge like this,” seconded a former Washington official. “And who knows what a ‘greenhouse gas emission’ is in the real world?” A lobbyist agreed: “Climate change, unfortunately, has become too politicized … I’d rather talk about decarbonization than climate change.”

Not everyone was as willing to shift to decarbonization, but most welcomed some form of specificity. “I’ve always tried to reframe climate change to be more personal and to recognize it is literally the biggest health challenge of our lives,” the former official said. The VC said we should “get back to the basics of, are you in the energy business? Are you in the agriculture business? Are you in transportation, logistics, manufacturing?”

“You're in a business,” they added, “there is no climate business.”

Not everyone hated “climate” quite as much — but others mentioned a phrase including the word. One think tanker wanted to nix “climate emergency.” Another scholar said: “I think the ‘climate justice’ term — not the idea — but I think the term got spread so widely that it became kind of difficult to understand what it was even referring to.” And one climate scientist didn’t have a problem with climate change, per se, but did say that people should pare back how they discuss it and back off “the notion that climate change will result in human extinction, or the sudden and imminent end to human civilization.”

There were other points of agreement. Four people wanted to ban “net zero” or “carbon neutrality.” One scientist said activists should back off fossil gas — “I know we’re always trying to try convince people of something, but, like, the entire world calls it ’natural gas’” — and another scientist said that they wished people would stop “micromanaging” language: “People continually changing jargon to try and find the magic words that make something different than it is — that annoys me.”

Two more academics added they wish to banish discussion of “overshoot”: “It’s not clear if it's referring to temperatures or emissions — I just don't think it's a helpful frame for thinking about the problem.”

“Unit economics,” “greenwashing,” and — yes — the whole spectrum of hydrogen colors came in for a lashing. But perhaps the most distinctive ban suggestion came from Todd Stern, the former chief U.S. climate diplomat, who negotiated the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement.

“I hate it when people say ’are you going to COP?’” he told me, referring to the United Nations’ annual climate summit, officially known as the Conference of the Parties. His issue wasn’t calling it “COP,” he clarified. It was dropping the definite article.

“The way I see it, no one has the right to suddenly become such intimate pals with ‘COP.’ You go to the ball game or the conference or what have you. And you go to ‘the COP,’” he said. “I am clearly losing this battle, but no one will ever hear me drop the ‘the.’”

Now, since I talked to Stern, the United States has moved to drop the COP entirely — with or without the “the” — because Trump took us out of the climate treaty under whose aegis the COP is held. But precision still counts, even in unfriendly times. And throughout the rest of this package, you’ll find insiders trying to find a path forward in thoughtful, insightful, and precise ways.

You’ll also find them remaining surprisingly upbeat — and even more optimistic, in some ways, than they were last year. Twelve months ago, 30% of our insider panel thought China would peak its emissions in the 2020s; this year, a plurality said the peak would come this decade. Roughly the same share of respondents this year as last year thought the U.S. would hit net zero in the 2060s. Trump might be setting back American climate action in the near term. But some of the most important long-term trends remain unchanged.

OUR PANEL INCLUDED… Gavin Schmidt, director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies | Ken Caldeira, senior scientist emeritus at the Carnegie Institution for Science and visiting scholar at Stanford University | Kate Marvel, research physicist at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies | Holly Jean Buck, associate professor of environment and sustainability at the University at Buffalo | Kim Cobb, climate scientist and director of the Institute at Brown for Environment and Society | Jennifer Wilcox, chemical engineering professor at the University of Pennsylvania and former U.S. Assistant Secretary for Fossil Energy and Carbon Management | Michael Greenstone, economist and director of the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago | Solomon Hsiang, professor of global environmental policy at Stanford University | Chris Bataille, global fellow at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy | Danny Cullenward, senior fellow at the Kleinman Center for Energy Policy at the University of Pennsylvania | J. Mijin Cha, environmental studies professor at UC Santa Cruz and fellow at Cornell University’s Climate Jobs Institute | Lynne Kiesling, director of the Institute for Regulatory Law and Economics at Northwestern University | Daniel Swain, climate scientist at the University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources | Emily Grubert, sustainable energy policy professor at the University of Notre Dame | Jon Norman, president of Hydrostor | Chris Creed, managing partner at Galvanize Climate Solutions | Amy Heart, senior vice president of public policy at Sunrun | Kate Brandt, chief sustainability officer at Google | Sophie Purdom, managing partner at Planeteer Capital and co-founder of CTVC | Lara Pierpoint, managing director at Trellis Climate | Andrew Beebe, managing director at Obvious Ventures | Gabriel Kra, managing director and co-founder of Prelude Ventures | Joe Goodman, managing partner and co-founder of VoLo Earth Ventures | Erika Reinhardt, executive director and co-founder of Spark Climate Solutions | Dawn Lippert, founder and CEO of Elemental Impact and general partner at Earthshot Ventures | Rajesh Swaminathan, partner at Khosla Ventures | Rob Davies, CEO of Sublime Systems | John Arnold, philanthropist and co-founder of Arnold Ventures | Gabe Kleinman, operating partner at Emerson Collective | Amy Duffuor, co-founder and general partner at Azolla Ventures | Amy Francetic, managing general partner and founder of Buoyant Ventures | Tom Chi, founding partner at At One Ventures | Francis O’Sullivan, managing director at S2G Investments | Cooper Rinzler, partner at Breakthrough Energy Ventures | Gina McCarthy, former administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency | Neil Chatterjee, former commissioner of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission | Representative Scott Peters, member of the U.S. House of Representatives | Todd Stern, former U.S. special envoy for climate change | Representative Sean Casten, member of the U.S. House of Representatives | Representative Mike Levin, member of the U.S. House of Representatives | Zeke Hausfather, climate research lead at Stripe and research scientist at Berkeley Earth | Shuchi Talati, founder and executive director of the Alliance for Just Deliberation on Solar Geoengineering | Nat Bullard, co-founder of Halcyon | Bill McKibben, environmentalist and founder of 350.org | Ilaria Mazzocco, senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies | Leah Stokes, professor of environmental politics at UC Santa Barbara | Noah Kaufman, senior research scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy | Arvind Ravikumar, energy systems professor at the University of Texas at Austin | Jessica Green, political scientist at the University of Toronto | Jonas Nahm, energy policy professor at Johns Hopkins SAIS | Armond Cohen, executive director of the Clean Air Task Force | Costa Samaras, director of the Scott Institute for Energy Innovation at Carnegie Mellon University | John Larsen, partner at Rhodium Group | Alex Trembath, executive director of the Breakthrough Institute | Alex Flint, executive director of the Alliance for Market Solutions

The Heatmap Insiders Survey of 55 invited expert respondents was conducted by Heatmap News reporters during November and December 2025. Responses were collected via phone interviews. All participants were given the opportunity to record responses anonymously. Not all respondents answered all questions.