You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

The raw material of America’s energy transition is poised for another boom.

In the town of Superior, Arizona, there is a hotel. In the hotel, there is a room. And in the room, there is a ghost.

Henry Muñoz’s father owned the building in the early 1980s, back when it was still a boarding house and the “Magma” in its name, Hotel Magma, referred to the copper mine up the hill. One night, a boarder from Nogales, Mexico, awoke to a phantom trying to pin her to the wall with the mattress; naturally, she demanded a new room. When Muñoz, then in his fearless early 20s, heard this story from his father, he became curious. Following his swing shift at the mine, Muñoz posted himself to the room with a six-pack of beer and passed the hours until dawn drinking and waiting for the spirit to make itself known.

Muñoz didn’t see a ghost that night, but he has since become well acquainted with others in town. There is the Mexican bakery, which used to sell pink cookies but now opens only when the late owner’s granddaughter feels up to it. There’s the old Magma Club, its once-segregated swimming pool — available one day a week to Hispanics — long since filled in. Muñoz can still point out where all the former bars were on Main Street, the ones that drew crowds of carousing miners in the good years before copper prices plunged in 1981 and Magma boarded up and left town. Now their dusty windows are what give out-of-towners from nearby Phoenix reason to write off Superior as “dead.”

“What happens when a mine closes, the hardship that brings to people — today’s generation has never experienced that,” Muñoz told me.

Superior is home to about 2,400 people, less than half its population when the mine was booming. To tourists zipping past on U.S. 60 to visit the Wild West sites in the Superstition Mountains, it might look half a step away from becoming a ghost town, itself. As recently as 2018, pictures of Main Street were used as stock photos to illustrate things like “America’s worsening geographic inequality.”

But if you take the exit into town, it’s clear something in Superior is changing. The once-haunted boarding house has undergone a multi-million-dollar renovation into a boutique hotel, charging staycationers that make the hour drive south from Scottsdale $200 a night. Across the street, Bellas Cafe whips up terrific sandwiches in a gleaming, retro-chic kitchen. The Chamber of Commerce building, a little further down the block, has been painted an inviting shade of purple. And propped in the window of some of the storefronts with their lights on, you might even see a sign: WE SUPPORT RESOLUTION COPPER.

Resolution Copper’s offices are located in the former Magma Hospital, where Muñoz was born and where his mother died. People in hard hats and safety vests mill about the parking lot, miners without a mine, which is not an unusual sight in Superior these days — no copper has been sold out of the immediate area in over two decades. And yet just a nine-minute drive further up the hill and another 15-minute elevator ride down the deepest mine shaft in the country lies one of the world’s largest remaining copper deposits. It’s estimated to be 40 billion pounds, enough to meet a quarter of U.S. demand, according to the company’s analysis.

That’s “huge,” Adam Simon, an Earth and environmental sciences professor at the University of Michigan, told me, and not just in terms of sheer size.

“Copper is the most important metal for all technologies we think of as part of the energy transition: battery electric vehicles, grid-scale battery storage, wind turbines, solar panels,” Simon said. In May, he published a study with Lawrence Cathles, an Earth and atmospheric sciences researcher at Cornell University, which looked at 120 years of copper-mining data and found that just to meet the demands of “business as usual,” the world will need 115% more of the material between 2018 and 2050 than has been previously mined in all of human history, even with recycling rates taken into account.

Aluminum, used in high-voltage lines, is sometimes floated as a potential substitute, but it’s not as good of a conductor, and copper is almost always the preferred metal in batteries and electricity generation. Renewables are particularly copper-intensive; one offshore wind turbine can require up to 29 tons. What lies in the hills behind Superior, then, represents “millions of electric vehicles, millions of wind turbines, millions of solar panels. And it’s also lots of jobs, from top to bottom — jobs for people with bachelor’s degrees in engineering, mining, geology, and environmental science, all the way down to security officers and truck drivers,” Simon said. He added: “The world will need more copper year over year for both socioeconomic improvement in the Global South and also the energy transition, and neither of those can happen without increasing the amount of copper that we produce.”

Muñoz insisted to me that the promises of jobs and a robust local economy are a kind of Trojan horse. “Everybody’s getting drunk and having a good time: ‘Oh, look at the gift they brought us!’” he said of Superior’s support for Resolution Copper. “But at night, they’re going to sneak out of that horse, and they’re going to leave an environmental disaster.”

For now, though, the copper has just one catch: Resolution isn’t allowed to touch it.

If not for a painted sign declaring the ground HOLY LAND, there would be nothing visible to suggest the 16 oak-shaded tent sites over Resolution Copper’s ore body were anything particularly special. The Oak Flat campground is less than five miles past Superior, but at an elevation of nearly 4,000 feet, it can feel almost 10 degrees Fahrenheit cooler. On the late June day that I visited with Muñoz, Sylvia Delgado, and Orlando “Marro” Perea — the leaders of the Concerned Citizens and Retired Miners Coalition — the floor of the East Valley was 113 degrees Fahrenheit, and the altitude offered only limited relief.

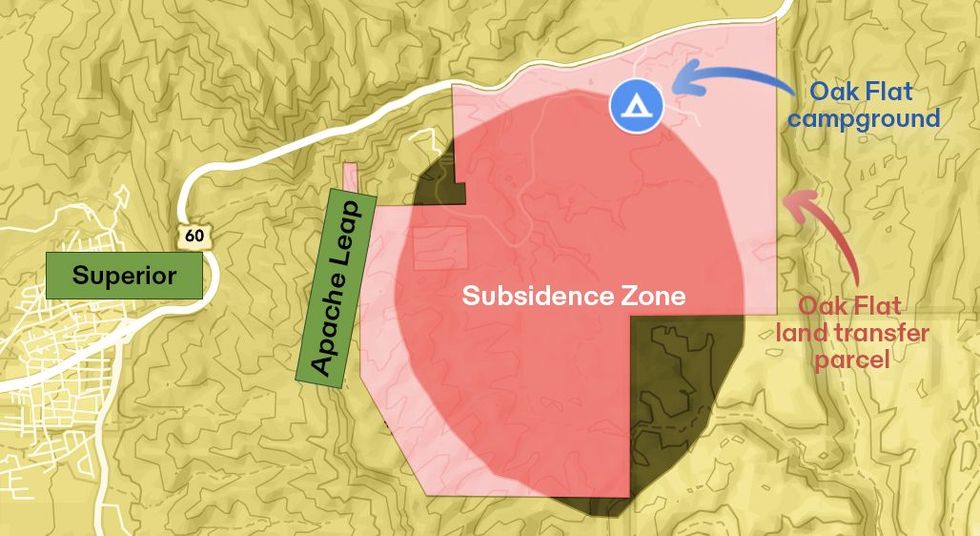

Directly below us and to the east of the campground, beneath a bouldery, yucca-studded desert, lies the copper deposit. At 7,000 or so feet deep, extracting it would require an advanced mining process called block caving, in which ore is collected from below through what is essentially a controlled cave-in, like sand slipping through the neck of an hourglass.

Muñoz, a fifth-generation miner, prefers the metaphor of going to the dentist. “They drill out your tooth and refill it: that’s basically traditional cut-and-fill mining,” he told me. “Block cave, on the other hand, would be going to the dentist and having them pull out the whole molar. It just leaves a vacant hole.” In this case, the resulting cavity would be almost two miles wide and over 1,000 feet deep by the time the ore was exhausted sometime in the 2060s.

Even four decades is just a blink of an eye for Oak Flat, though, where human history goes back at least 1,500 years; anthropologists say the mine’s sinkhole would swallow countless Indigenous burial locations and archeological sites, including petroglyphs depicting antlered animals that Muñoz and Perea showed me hidden deep in the rocks. Even more alarmingly, the subsidence would obliterate Chí'chil Biłdagoteel, the Western Apache’s name for the lands around Oak Flat, which are sacred to at least 10 federally recognized tribes. The members of the San Carlos Apache who are leading the opposition effort, and use the location for a four-day-long girlhood coming-of-age ceremony, say it is the only place where their prayers can reach the Creator directly.

Mining and Indigenous sovereignty have been at odds in Arizona for over a century. “The Apache is as near the lobo, or wolf of the country, as any human being can be to a beast,” The New York Times wrote in 1859, claiming the tribe was “the greatest obstacle to the operations of the mining companies” in the area. Three years later, the U.S. Army’s departmental commander ordered Apache men killed “wherever found,” the social archaeologist John Welch writes in his eye-opening historical survey of the region, in which he also advocates for using the term “genocide” to describe the government’s policies. That violence still casts a shadow in Superior: Apache Leap, an astonishing escarpment that looms over the town and backs up against Oak Flat, is named for a legend that cornered Apache warriors jumped to their deaths from its cliffs rather than surrender to the U.S. Cavalry.

As the Apache were being forced onto reservations and into residential boarding schools during the late 1890s, a treaty with the government set aside Oak Flat for protection. The land was later fortified against mining by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, with the federal protections reconfirmed by the Nixon administration in the 1960s. (The defunct Magma Mine that fueled the first copper boom in Superior is located just off this 760-acre “Oak Flat Withdrawal Area.”)

In 1995, the enormity of the Oak Flat ore body — and the billions it would be worth if it could be accessed — started to become apparent. The British and Australian mining companies Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton formed a U.S. subsidiary, Resolution Copper, which bought the old Magma mine and began to lobby Arizona politicians to sign over the neighboring parcel of Oak Flat. Between 2004 and 2013, lawmakers from the state introduced 11 different land transfer bills into Congress, none of which managed to earn broad support.

Then, in December 2014, President Barack Obama signed a must-pass defense spending bill. On page 1,103 was a midnight rider, inserted by Arizona Republican Senators John McCain and Jeff Flake, which authorized a land transfer of 2,400 acres of Tonto National Forest, including Oak Flat, to Resolution Copper in exchange for private land the company had bought in other parts of the state. (Flake previously worked as a paid lobbyist for a Rio Tinto uranium mine, and the company contributed to McCain’s 2014 Senate campaign.)

The senators’ rider also included an odd little twist. While the National Environmental Policy Act requires the Forest Service to conduct an environmental impact statement for a potential mine, the bill stipulated that the land transfer to Resolution Copper had to be completed within a 60-day window of the final environmental impact statement’s release, regardless of what the FEIS found.

After six years of study, the FEIS was rushed to publication by President Donald Trump in the final five days of his term, triggering that 60-day countdown. President Biden rescinded Trump’s FEIS once he took office in 2021, pending further consultation with the tribes, but the clock will begin anew once a revised FEIS is released, potentially later this year. (The new FEIS was expected last summer, but the Forest Service has since reported there is no timeline for its release. The agency declined to comment to Heatmap for this story, citing ongoing litigation.)

A spokesperson for Resolution Copper told me that the company is “committed to being a good steward of the land, air, and water throughout the entirety of this project,” and described programs to restore the local ecology and preserve certain natural features, including Apache Leap. “At each step,” the spokesperson said, “we have taken great care to solicit and act upon the input of our Native American and other neighbors. We have made many changes to the project scope to accommodate those concerns and will continue those efforts over the life of the project.”

Meanwhile, Apache Stronghold — the San Carlos Apache-led religious nonprofit opposing the mine — filed a lawsuit to block the land transfer, arguing that the destruction of Oak Flat infringes on their First Amendment right to practice their religion. The lower courts haven’t agreed, citing a controversial 1988 decision against tribes who made a similar argument in defense of a sacred grove of trees in California. Apache Stronghold, joined by the religious liberty group Becket, is now asking the U.S. Supreme Court to hear its case, a decision that is expected any day now. Nearly everyone I spoke with for this story, however, was pessimistic that the Justices would agree to hear the battle over Oak Flat, meaning the lower court’s ruling against Apache Stronghold would stand.

If Mila Besich could have it her way, Biden would visit Superior. He’d marvel at Apache Leap and Picketpost Mountain, visit the impressive new Superior Enterprise Center — paid for partially with money from his 2021 American Rescue Plan Act — and maybe wrap up the day with a purple scoop of prickly pear ice cream from Felicia’s Ice Cream Shop. And, most importantly, he’d hear her pitch: that “Superior and the state of Arizona have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to be the leader in advancing your green energy strategy.” She says Superior — and America — needs this mine.

Superior is a blue town, and Besich, its mayor, is a Democrat, which means she has found herself in the awkward position of defending Resolution Copper against colleagues like Congressman Raúl Grijalva of Tucson and Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, who have introduced unsuccessful bills in Congress to prevent the land transfer. There is something of a bitter irony, too, in seeing her party tout the economic upsides of the energy transition while standing in the way of Superior’s mine, which would employ an average of 1,434 workers per year and add over $1 billion annually to Arizona’s economy during its lifespan, according to the FEIS.

“Every mayor wants more jobs in their community,” Besich told me simply. But, she also pointed out, “Copper is critical to the green economy, so if we want the green economy, we should want to be mining American copper.”

Superior, of course, isn’t just any town. “Everybody here either worked in the mines or had family that worked in the mines,” James Schenck, a former employee of Resolution Copper who supports the mine and serves as the treasurer for Rebuild Superior, a nonprofit working to diversify the local economy, told me. “They understand the downsides, and some of them, for a while, were having a hard time understanding how this is different than what went on before.”

Though everyone seems to be on cordial terms — at one point during my visit, I was having lunch with Muñoz and Delgado when Besich walked in, and everyone smiled politely at one another — there are still clear factions. A Facebook group for locals warns against “posts concerning DRAMA, POLITICS, RELIGION, and MINING,” presumably the same topics to be avoided at family Thanksgivings.

The critical mineral experts I talked to for this story, though, said Schenck is largely right on that point. “Mining in 2024 is radically different than mining in 1954 or in 1904,” Simon told me. “It is really surgical.”

Muñoz is one of those in town who still isn’t buying it, and has converted his garage into an interpretive center for exposing the perceived infiltrators. As soft classic rock played over the speakers and a fan whirred to keep us cool, he showed me the 3D model he had commissioned of the Oak Flat sinkhole, with a miniature Eiffel Tower subsumed in its crater for scale. Laid out on a table on the other side of the room was a row of six dictionary-thick, spiral-bound sections of the FEIS, their most pertinent sections bookmarked. On the walls, Muñoz had hung pictures of comparable tailings sites in other parts of the world — cautionary tales of the hazards posed during the long lifespan of mines. (Including the water demands, no small concern in a place like Arizona, which opens a whole other can of worms).

“I use my experience to educate the people,” Muñoz said. “This isn’t what it’s made out to be. They’re going to play you.”

Muñoz was employed at the Magma Copper mine until 1982, when he was 27. “One day they said, ‘We’re shutting down.’ They folded up just like a carnival does on Monday morning,” he recalled. The abrupt departure devastated Superior: In These Times described the following years as an “economic cataclysm” for the town. By 1989, the median household income was just $16,118 compared to $36,806 in Queen Creek, the nearest Phoenix suburb just a 45-minute drive away.

“I witnessed grown men cry,” Muñoz said. “Men who’d been in the mines pretty close to 30 years — they never knew nothing else.” His father, the former boarding house owner, was among them: “He had limited writing abilities and what have you. He was 58. People lost their homes here. They lost their cars. There were divorces. Some people committed suicide. The drinking, the drugs. It was a bad time.”

Muñoz went on food stamps and unemployment. “This generation that is coming up, they’ve never experienced that,” he said. “They’ve never experienced a repossession note in the mail from the bank. They’ve never experienced a disconnection notice hanging from your front door knob. And they’ve never experienced calling up the utilities and saying, ‘Hey, can you wait until Friday when my unemployment check comes in?’”

Superior’s story isn’t unique; Arizona’s Copper Triangle is a constellation of hollowed-out company towns. Like many other out-of-work Magma miners, Muñoz eventually found a job at San Manuel, a BHP-owned block cave mine about an hour south of Superior. Then, in 1999, copper prices stuttered again, and by 2003, it shut down, too.

Muñoz had just returned from a car show in San Manuel when we met in his garage, and he reported it was still a sorry sight. “The main grocery store is closed, the Subway, all the buildings are boarded up, and the schools are shut down,” he said. The mine “just abandoned that town.”

Even as Muñoz and the Concerned Citizens and Retired Miners Coalition work with Apache Stronghold and national environmentalist groups like HECHO, the Sierra Club, and the National Wildlife Federation try to block Resolution Copper’s mine, there is a distinct feeling in Superior of its inevitability. Schenck, the treasurer for Rebuild Superior, told me he suspects just “10% or 15%” of people in town are “against the project.”

“My personal belief is this copper deposit is going to be developed at some point,” Schenck said. “It’s too important.”

Besich, the mayor, gave this impression too. “What people need to understand is, this ore body is not going anywhere,” she said. “Someone will mine it in the future.” She views Superior and the copper industry as partners in an “arranged marriage,” and her job as mayor is helping them “figure out how to get along.”

From the outside, though, Resolution Copper looks more like a sugar daddy. To date, Rio Tinto and BHP have spent more than $2 billion combined pursuing the Oak Flat mine, including pumping money into the Chamber of Commerce building, the Enterprise Center, and the fire department. When the town of Kearny, downstream of the mine’s proposed tailings site, needed a new ambulance, Resolution Copper offered to help foot the bill. Local high schoolers and tribal members can even apply for Resolution Copper scholarships.

Critics say Resolution Copper is buying political and social influence in the Copper Corridor, a modern-day iteration of the propaganda tactics that swept aside the Apache in the late 1800s. Rio Tinto and BHP “remain committed to influencing U.S. government decisions about the use of public lands and minerals, regardless of additional harms to those lands, to Native Americans, or to National Register historic sites and sacred places,” the archaeologist Welch wrote in his Oak Flat study.

Rio Tinto is infamous even in the mining industry for its poor history of handling community- and heritage-related concerns. To pick a recent example, the company drew international condemnation for its 2020 destruction of the Juukan Gorge cave in Western Australia, a sacred site to the Aboriginal people that had evidence of continuous human occupation going back to the Ice Age. Though Rio Tinto had the legal right to destroy the 45,000-year-old caves, “it is hard to believe community engagement is being taken seriously” by the company, Glynn Cochrane, a former Rio Tinto senior advisor, said in a testimony in the aftermath. Archaeologists and sympathetic politicians have warned that the cultural and spiritual loss caused by mining Oak Flat would be like a second Juukan Gorge.

The San Carlos Apache are not a monolith, however, and the community has differing beliefs about the cultural importance of Oak Flat. Tribal members who support the mine or work for Resolution Copper are often cited by non-Native supporters as proof of Apache Stronghold’s supposedly arbitrary defense of Oak Flat. (Apache Stronghold, which is on a prayer journey to petition the Supreme Court, did not return Heatmap’s request for comment.)

Muñoz and his team are specifically worried about how Superior, the town, will make out. U.S. copper smelters are already at capacity, meaning Resolution Copper would likely send much if not all of the raw copper extracted at Oak Flat to China for processing. (Rio Tinto’s largest shareholder is the Aluminum Corporation of China.) The spokesperson for Resolution Copper told me that it’s the company’s priority to process the ore domestically, and Rio Tinto does have its own facility in the U.S., the Kennecott copper smelting facility in Utah. Yet it hasn’t committed publicly to processing the Arizona ore there, and it’s far from clear that it even has the capacity to do so.

For Simon, the University of Michigan professor, that shouldn’t be a deterrent: “If we mine more copper here and it just means we have to export it — who cares?” he pushed back. “If it has to go to China and they smelt it, then you send it to China and they smelt it. Climate is the prize, and if we want to mitigate our impact, we’ve got to do it. There are no ifs, ands, or buts.”

Oak Flat is also located outside of Superior’s town limits, meaning the community would only recoup about $500,000 in tax revenue, on the high end, from the mine annually, according to the 2021 FEIS — Schenek told me the town’s budget is around $3 million, so it’s hardly insignificant, though it is peanuts compared to the $38 million the state would reap. The FEIS additionally estimated that only about a quarter of the mine’s eventual employees would actually “seek to live in or near Superior;” many would choose instead to commute the hour or so from Phoenix’s Maricopa County.

Because of technological advances in mining and robotics, the mine also won’t bring back the physical jobs locals remember from the 1970s — by Resolution Copper’s own admission. Besich, at least, isn’t bothered by this detail: “In all reality, I don’t see my children and their peers wanting to do the manual physical labor that my grandfather, my father, and certainly my great-grandfather did,” she told me. “So the change in technique is good, and I think that it’s actually better for the environment in the long term.” She added that Resolution Copper’s investment in things like local infrastructure and worker training programs will compensate for the comparably insignificant tax revenue the town will otherwise receive, ensuring Superior gets a fair cut of the bonanza.

What supporters and opponents of the mine can agree on is that Superior must avoid the devastation of the 1980s if or when the Oak Flat mine is exhausted in 40 or more years. Besich and Schenck told me their vision is for Superior to be a town with a mine, not a mining town. But is such a thing even possible? In recent years, Superior has tried to position itself as an outdoor recreation gateway to the many climbing routes and hiking trails in the area. Yet I struggle to imagine anyone would want to vacation or recreate so close to a massive mining operation.

Muñoz believes Superior should throw itself entirely into tourism, which brings in three times as much revenue as the copper industry in Arizona. He dismissed arguments that losing the mine this far into negotiations and preparations would set the town back two decades, telling me about a conversation he had with Vicky Peacey, the president of Resolution Copper. “She said, ‘How do I tell my 300-plus employees that they don’t have a job?’” he recalled. “I said, ‘The same way BHP told the 3,300 in San Manuel they didn’t have a job. Magma Copper didn’t have a problem telling us we didn’t have a job in ‘82.”

Whatever gets decided about Oak Flat will reverberate far beyond Superior, though. “We’ve got to keep our eyes on the prize,” Simon told me. “And if the prize is mitigating human impacts on climate, and that requires the energy transition, and that requires copper, and we have a potential mine in Arizona that would provide 500,000 tons of copper every year for decades — we need to do that.”

At the end of my day in Superior, I went with Muñoz and Delgado, another former miner, to visit the haunted boarding house.

The renovated interior was surprisingly beautiful, decorated with period-appropriate details like iron bed frames, clawfoot bathtubs, and lace curtains that softened the harshness of the mid-afternoon light. Though even the FEIS warns that “mining in Arizona has followed a ‘boom and bust’ cycle, which potentially leads to great economic uncertainty,” it was with a pang that I imagined the building one day falling back into disrepair. It, and the town, had survived too much.

After peeking into Room 103, where Muñoz had passed his tipsy night all those decades ago, we asked the friendly woman working the front desk if she’d had any supernatural experiences herself — surely she’d seen the mattress-flipping phantom, or swinging chandeliers, or perhaps a white-boot miner who’d come down from the hills?

To our disappointment, she shook her head. For now, whatever ghosts there once might have been in Superior had gone.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to include comment from Resolution Copper.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

The proportion of voters who strongly oppose development grew by nearly 50%.

During his State of the Union address Tuesday night, President Donald Trump attempted to stanch the public’s bleeding support for building the data centers his administration says are necessary to beat China in the artificial intelligence race. With “many Americans” now “concerned that energy demand from AI data centers could unfairly drive up their electricity bills,” Trump said, he pledged to make major tech companies pay for new power plants to supply electricity to data centers.

New polling from energy intelligence platform Heatmap Pro shows just how dramatically and swiftly American voters are turning against data centers.

Earlier this month, the survey, conducted by Embold Research, reached out to 2,091 registered voters across the country, explaining that “data centers are facilities that house the servers that power the internet, apps, and artificial intelligence” and asking them, “Would you support or oppose a data center being built near where you live?” Just 28% said they would support or strongly support such a facility in their neighborhood, while 52% said they would oppose or strongly oppose it. That’s a net support of -24%.

When Heatmap Pro asked a national sample of voters the same question last fall, net support came out to +2%, with 44% in support and 42% opposed.

The steep drop highlights a phenomenon Heatmap’s Jael Holzman described last fall — that data centers are "swallowing American politics,” as she put it, uniting conservation-minded factions of the left with anti-renewables activists on the right in opposing a common enemy.

The results of this latest Heatmap Pro poll aren’t an outlier, either. Poll after poll shows surging public antipathy toward data centers as populists at both ends of the political spectrum stoke outrage over rising electricity prices and tech giants struggle to coalesce around a single explanation of their impacts on the grid.

“The hyperscalers have fumbled the comms game here,” Emmet Penney, an energy researcher and senior fellow at the right-leaning Foundation for American Innovation, told me.

A historian of the nuclear power sector, Penney sees parallels between the grassroots pushback to data centers and the 20th century movement to stymie construction of atomic power stations across the Western world. In both cases, opponents fixated on and popularized environmental criticisms that were ultimately deemed minor relative to the benefits of the technology — production of radioactive waste in the case of nuclear plants, and as seems increasingly clear, water usage in the case of data centers.

Likewise, opponents to nuclear power saw urgent efforts to build out the technology in the face of Cold War competition with the Soviet Union as more reason for skepticism about safety. Ditto the current rhetoric on China.

Penney said that both data centers and nuclear power stoke a “fear of bigness.”

“Data centers represent a loss of control over everyday life because artificial intelligence means change,” he said. “The same is true about nuclear,” which reached its peak of expansion right as electric appliances such as dishwashers and washing machines were revolutionizing domestic life in American households.

One of the more fascinating findings of the Heatmap Pro poll is a stark urban-rural divide within the Republican Party. Net support for data centers among GOP voters who live in suburbs or cities came out to -8%. Opposition among rural Republicans was twice as deep, at -20%. While rural Democrats and independents showed more skepticism of data centers than their urbanite fellow partisans, the gap was far smaller.

That could represent a challenge for the Trump administration.

“People in the city are used to a certain level of dynamism baked into their lives just by sheer population density,” Penney said. “If you’re in a rural place, any change stands out.”

Senator Bernie Sanders, the democratic socialist from Vermont, has championed legislation to place a temporary ban on new data centers. Such a move would not be without precedent; Ireland, transformed by tax-haven policies over the past two decades into a hub for Silicon Valley’s giants, only just ended its de facto three-year moratorium on hooking up data centers to the grid.

Senator Josh Hawley, the Missouri Republican firebrand, proposed his own bill that would force data centers off the grid by requiring the complexes to build their own power plants, much as Trump is now promoting.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, you have Republicans such as Mississippi Governor Tate Reeves, who on Tuesday compared halting construction of data centers to “civilizational suicide.”

“I am tempted to sit back and let other states fritter away the generational chance to build. To laugh at their short-sightedness,” he wrote in a post on X. “But the best path for all of us would be to see America dominate, because our foes are not like us. They don’t believe in order, except brutal order under their heels. They don’t believe in prosperity, except for that gained through fraud and plunder. They don’t think or act in a way I can respect as an American.”

Then you have the actual hyperscalers taking opposite tacks. Amazon Web Services, for example, is playing offense, promoting research that shows its data centers are not increasing electricity rates. Claude-maker Anthropic, meanwhile, issued a de facto mea culpa, pledging earlier this month to offset all its electricity use.

Amid that scattershot messaging, the critical rhetoric appears to be striking its targets. Whether Trump’s efforts to curb data centers’ impact on the grid or Reeves’ stirring call to patriotic sacrifice can reverse cratering support for the buildout remains to be seen. The clock is ticking. There are just 36 weeks until the midterm Election Day.

The public-private project aims to help realize the president’s goal of building 10 new reactors by 2030.

The Department of Energy and the Westinghouse Electric Company have begun meeting with utilities and nuclear developers as part of a new project aimed at spurring the country’s largest buildout of new nuclear power plants in more than 30 years, according to two people who have been briefed on the plans.

The discussions suggest that the Trump administration’s ambitious plans to build a fleet of new nuclear reactors are moving forward at least in part through the Energy Department. President Trump set a goal last year of placing 10 new reactors under construction nationwide by 2030.

The project aims to purchase the parts for 8 gigawatts to 10 gigawatts of new nuclear reactors, the people said. The reactors would almost certainly be AP1000s, a third-generation reactor produced by Westinghouse capable of producing up to 1.1 gigawatts of electricity per unit.

The AP1000 is the only third-generation reactor successfully deployed in the United States. Two AP1000 reactors were completed — and powered on — at Plant Vogtle in eastern Georgia earlier this decade. Fifteen other units are operating or under construction worldwide.

Representatives from Westinghouse and the Energy Department did not respond to requests for comment.

The project would use government and private financing to buy advanced reactor equipment that requires particularly long lead times, the people said. It would seek to lower the cost of the reactors by placing what would essentially be a single bulk order for some of their parts, allowing Westinghouse to invest in and scale its production efforts. It could also speed up construction timelines for the plants themselves.

The department is in talks with four to five potential partners, including utilities, independent power producers, and nuclear development companies, about joining the project. Under the plan, these utilities or developers would agree to purchase parts for two new reactors each. The program would be handled in part by the department’s in-house bank, the Loan Programs Office, which the Trump administration has dubbed the Office of Energy Dominance Financing.

This fleet-based approach to nuclear construction has succeeded in the past. After the oil crisis struck France in the 1970s, the national government responded by planning more than three-dozen reactors in roughly a decade, allowing the country to build them quickly and at low cost. France still has some of the world’s lowest-carbon electricity.

By comparison, the United States has built three new nuclear reactors, totaling roughly 3.5 gigawatts of capacity, since the year 2000, and it has not significantly expanded its nuclear fleet since 1990. The Trump administration set a goal in May to quadruple total nuclear energy production — which stands at roughly 100 gigawatts today — to more than 400 gigawatts by the middle of the century.

The Trump administration and congressional Republicans have periodically announced plans to expand the nuclear fleet over the past year, although details on its projects have been scant.

Senator Dave McCormick, a Republican of Pennsylvania, announced at an energy summit last July that Westinghouse was moving forward with plans to build 10 new reactors nationwide by 2030.

In October, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick announced a new deal between the U.S. government, the private equity firm Brookfield Asset Management, and the uranium company Cameco to deploy $80 billion in new Westinghouse reactors across the United States. (A Brookfield subsidiary and Cameco have jointly owned Westinghouse since it went bankrupt in 2017 due to construction cost overruns.) Reuters reported last month that this deal aimed to satisfy the Trump administration’s 2030 goal.

While there have been other Republican attempts to expand the nuclear fleet over the years, rising electricity demand and the boom in artificial intelligence data centers have brought new focus to the issue. This time, Democratic politicians have announced their own plans to boost nuclear power in their states.

In January, New York Governor Kathy Hochul set a goal of building 4 gigawatts of new nuclear power plants in the Empire State.

In his State of the State address, Governor JB Pritzker of Illinois told lawmakers last week that he hopes to see at least 2 gigawatts of new nuclear power capacity operating in his state by 2033.

Meeting Trump’s nuclear ambitions has been a source of contention between federal agencies. Politico reported on Thursday that the Energy Department had spent months negotiating a nuclear strategy with Westinghouse last year when Lutnick inserted himself directly into negotiations with the company. Soon after, the Commerce Department issued an announcement for the $80 billion megadeal, which was big on hype but short on details.

The announcement threw a wrench in the Energy Department’s plans, but the agency now seems to have returned to the table. According to Politico, it is now also “engaging” with GE Hitachi, another provider of advanced nuclear reactors.

On nuclear tax credits, BLM controversy, and a fusion maverick’s fundraise

Current conditions: A third storm could dust New York City and the surrounding area with more snow • Floods and landslides have killed at least 25 people in Brazil’s southeastern state of Minas Gerais • A heat dome in Western Europe is pushing up temperatures in parts of Portugal, Spain, and France as high as 15 degrees Celsius above average.

The Department of Energy’s in-house lender, the Loan Programs Office — dubbed the Office of Energy Dominance Financing by the Trump administration — just gave out the largest loan in its history to Southern Company. The nearly $27 billion loan will “build or upgrade over 16 gigawatts of firm reliable power,” including 5 gigawatts of new gas generation, 6 gigawatts of uprates and license renewals for six different reactors, and more than 1,300 miles of transmission and grid enhancement projects. In total, the package will “deliver $7 billion in electricity cost savings” to millions of ratepayers in Georgia and Alabama by reducing the utility giant’s interest expenses by over $300 million per year. “These loans will not only lower energy costs but also create thousands of jobs and increase grid reliability for the people of Georgia and Alabama,” Secretary of Energy Chris Wright said in a statement.

Over in Utah, meanwhile, the state government is seeking the authority to speed up its own deployment of nuclear reactors as electricity demand surges in the desert state. In a letter to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission dated November 10 — but which E&E News published this week — Tim Davis, the executive director of Utah’s Department of Environmental Quality, requested that the federal agency consider granting the state the power to oversee uranium enrichment, microreactor licensing, fuel storage, and reprocessing on its own. All of those sectors fall under the NRC’s exclusive purview. At least one program at the NRC grants states limited regulatory primacy for some low-level radiological material. While there’s no precedent for a transfer of power as significant as what Utah is requesting, the current administration is upending norms at the NRC more than any other government since the agency’s founding in 1975.

Building a new nuclear plant on a previously undeveloped site is already a steep challenge in electricity markets such as New York, California, or the Midwest, which broke up monopoly utilities in the 1990s and created competitive auctions that make decade-long, multibillion-dollar reactors all but impossible to finance. A growing chorus argues, as Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote, that these markets “are no longer working.” Even in markets with vertically-integrated power companies, the federal tax credits meant to spur construction of new reactors would make financing a greenfield plant is just as impossible, despite federal tax credits meant to spur construction of new reactors. That’s the conclusion of a new analysis by a trio of government finance researchers at the Center for Public Enterprise. The investment tax credit, “large as it is, cannot easily provide them with upfront construction-period support,” the report found. “The ITC is essential to nuclear project economics, but monetizing it during construction poses distinct challenges for nuclear developers that do not arise for renewable energy projects. Absent a public agency’s ability to leverage access to the elective payment of tax credits, it is challenging to see a path forward for attracting sufficient risk capital for a new nuclear project under the current circumstances.”

Steve Pearce, Trump’s pick to lead the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management, wavered when asked about his record of pushing to sell off federal lands during his nomination hearing Wednesday. A former Republican lawmaker from New Mexico, Pearce has faced what the public lands news site Public Domain called “broad backlash from environmental, conservation, and hunting groups for his record of working to undermine public land protections and push land sales as a way to reduce the federal deficit.” Faced with questions from Democratic senators, Pearce said, “I’m not so sure that I’ve changed,” but insisted he didn’t “believe that we’re going to go out and wholesale land from the federal government.” That has, however, been the plan since the start of the administration. As Heatmap’s Jeva Lange wrote last year, Republicans looked poised to use their trifecta to sell off some of the approximately 640 million acres of land the federal government owns.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

At Tuesday’s State of the Union address, as I told you yesterday, Trump vowed to force major data center companies to build, bring, or buy their own power plants to keep the artificial intelligence boom from driving up electricity prices. On Wednesday, Fox News reported that Amazon, Google, Meta, Microsoft, xAI, Oracle, and OpenAI planned to come to the White House to sign onto the deal. The meeting is set to take place sometime next month. Data centers are facing mounting backlash. Developers abandoned at least 25 data centers last year amid mounting pushback from local opponents, Heatmap's Robinson Meyer recently reported.

Shine Technologies is a rare fusion company that’s actually making money today. That’s because the Wisconsin-based firm uses its plasma beam fusion technology to produce isotopes for testing and medical therapies. Next, the company plans to start recycling nuclear waste for fresh reactor fuel. To get there, Shine Technologies has raised $240 million to fund its efforts for the next few years, as I reported this morning in an exclusive for Heatmap. Nearly 63% of the funding came from biotech billionaire Patrick Soon-Shiong, who will join the board. The capital will carry the company through the launch of the world’s largest medical isotope producer and lay the foundations of a new business recycling nuclear waste in the early 2030s that essentially just reorders its existing assembly line.

Vineyard Wind is nearly complete. As of Wednesday, 60 of the project’s 62 turbines have been installed off the coast of Massachusetts. Of those, E&E News reported, 52 have been cleared to start producing power. The developer Iberdrola said the final two turbines may be installed in the next few days. “For me, as an engineer, the farm is already completed,” Iberdrola’s executive chair, Ignacio Sánchez Galán, told analysts on an earnings call. “I think these numbers mean the level of availability is similar for other offshore wind farms we have in operation. So for me, that is completed.”