You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

And that’s before we start talking about the tens of billions of dollars of investment required.

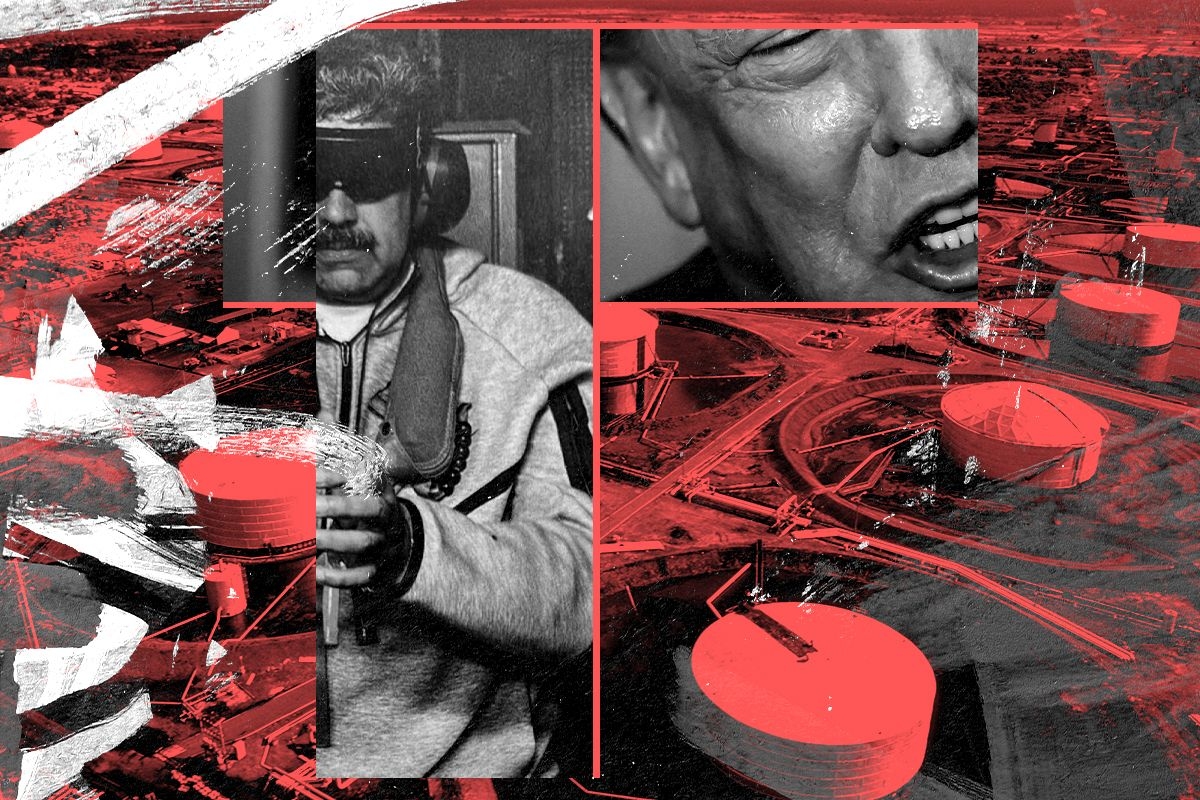

Donald Trump could not have been more clear about his intentions. Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro may be sitting in New York’s Metropolitan Detention Center on drugs and weapons charges, but the United States removed him from power — at least in part — because the Trump administration wants oil. And it wants American companies to get it.

“We’re going to have our very large United States oil companies, the biggest anywhere in the world, go in, spend billions of dollars, fix the badly broken infrastructure, the oil infrastructure, and start making money for the country,” Trump said over the weekend in a press conference following Maduro’s removal from Venezuela.

The country’s claimed crude oil reserves are the largest in the world, according to OPEC data, standing at just over 300 billion barrels, compared to around 45 billion in the United States and 267 billion in Saudi Arabia.

But having reserves and exploiting them are very different things. Before oil producers can start pumping, both the Venezuelan government and the U.S. oil companies will have to traverse several geopolitical and financial steps. Some of these could take weeks; others may take years. The entire process will cost tens of billions of dollars, if not more, at a time when oil prices are low. And American oil companies may well be leery about investing in a country with a long history of instability when it comes to foreign investment.

Venezuela produced over 3 million barrels per day though the 1960s until the late 1990s. Then came nationalization, decades of underinvestment, and harsh sanctions imposed in Trump’s first term to pressure the Maduro government, and most recently, a U.S. naval blockade imposed in December. As of last year, production had fallen to around a million barrels per day.

About 120,000 barrels per day winds up at U.S. Gulf Coast refineries built to process its heavy sour crude, courtesy of a rare license to operate granted to Chevron. (Chevron shares were up in early trading Monday morning.) But “for the most part, the Venezuela oil story has been a small amount of production all going to China,” Greg Brew, an analyst at the Eurasia Group, told me.

To get a sense of where Venezuela’s oil production capacity sits in the international context, Texas alone has produced more oil every year since 2018 than Venezuela’s all-time peak production of 3.7 million barrels per day in 1970. Canada, which produces a comparably heavy and sour crude, produced over 5 million barrels per day in 2025.

The immediate question is whether the United States will lift its blockade and allow oil to flow more freely. Venezuela’s monthly exports dropped dramatically in December to 19 million barrels, down from 27 million the month before, according to S&P Global Commodities data.

“If that happens,” oil analyst Rory Johnston told me about the potential to lift the blockade, “those barrels will still largely go to China.”

But even that is in question.

When asked on Face the Nation how the United States would “run” Venezuela, as Trump indicated, without an active military presence in the country, Secretary of State Marco Rubio indicated that the blockade would be a key pressure point. “That’s the sort of control the president is pointing to,” he said. The blockade “remains in place,” Rubio added, “and that’s a tremendous amount of leverage that will continue to be in place until we see changes.”

Even if the blockade were lifted, the next question over the medium to long term would be the lifting of U.S. sanctions, which have been in effect on Venezuela’s oil industry in their harshest form since 2019. With very few exceptions, these have prevented U.S. and other large oil companies from getting further involved with the country.

Sanctions are “why American companies either can’t or won’t buy Venezuela oil, and that keeps other buyers from not buying it as well,” Brew told me. “That’s another source of downward pressure on Venezuela oil exports.”

Even after it’s no longer literally illegal to work with Venezuela, however, there’s still the logistical and financial questions of long-term investments in Venezuela’s oil sector.

Venezuela would have to repair its connections to the international financial system, which have been strained by its defaults on tens of billions of debt. It would also likely have to overhaul its own laws around foreign investment in its oil industry that favor its state oil company PDVSA, according to Luisa Palacios, a former chairperson of Citgo, the (for now) majority-Venezuelan-owned energy company. Only then would U.S. oil companies likely have a plausible case to re-invest.

The next question is whether that investment would be worth it.

“Foreign companies are looking for an improvement in governance, the restoration of the rule of law, and an easing of U.S. oil sanctions,” Palacios wrote in a blog post for the Columbia Center on Global Energy Policy. “If the Venezuelan government were to commit to these reforms in a serious way (and the United States was therefore prepared to remove sanctions), an increase in oil production of 500,000 b/d-1 million b/d within a 2-year horizon, while optimistic, seems plausible” — though nowhere near the country’s 3.7 million-barrel peak.

Jefferies analyst Alejando Anibal Demichelis came to a similar conclusion in a note to clients, adding that “further increases beyond that level could be much more complex and costly.”

To get from here to there would require extensive investment in an environment where oil is plentiful and cheap. Oil prices saw their largest one-year decline last year since the onset of COVID in 2020.

“This is a moment where there’s oversupply,” Johnston told me. “Prices are down. It’s not the moment that you’re like, I’m going to go on a lark and invest in Venezuela.”

Venezuela will need that confidence to generate the necessary investments. The country’s oil industry “desperately needs more operational and financial support,” according to analysts at the consultancy Wood Mackenzie, which has estimated that it would require some $15 billion to $20 billion of investment over a decade to get production from existing operations to increase by 500,000 barrels per day.

Within six months to a year, Brew told me, “the volume of exports that could realistically be expected to increase is 200,000 to 400,000 barrels a day.” And that figure assumes “the stars align” in terms of the blockade, sanctions relief, and investment.

The “best case scenario,” Brew told me, is that tens of billions of dollars of U.S. investment flows into Venezuela as the blockade is lifted, sanctions are removed, and Venezuela reforms its laws to allow more foreign investment.

“Even there, I think realistically, it takes two years to get production from 1 million to 2 million barrels a day, and it costs a lot of money in a period amidst price conditions that are expected to be fairly soft,” he said.

As a rough guideline for what’s feasible over the long term, Iraq’s oil production rose from about 2 million barrels per day in 2002 to 4.7 million barrels by the end of the next decade, according to Wood Mackenzie. But that was at a time when oil prices were generally rising.

In any case, more oil is more oil, and it’s hard to see how Venezuela’s exports could get much lower. Industry analysts largely concluded that the operation to remove Maduro and put the United States in the driver’s seat would exert at least a mild downward pressure on oil prices.

But do major American oil companies want to get involved in the first place? “We’ve been expropriated from Venezuela two different times,” ExxonMobil chief executive Darren Woods told Bloomberg last year. Both Exxon and ConocoPhillips left the country in 2007 rather than accept new contracts with Venezuela’s state-owned oil company.

Brew is pessimistic. “I don’t see much of an upside in the short term,” he told me. That’s because the potential profits from reinvesting could be meager. When Maduro came to power in 2013, U.S. oil prices were over $90 a barrel, compared to around $60 today.

“But apart from commercial incentives, there is the incentive of, Okay the president wants us to do this. We can do it,” Brew said, but he cautioned, “I don’t think he’s in a position to leverage major US oil companies to go into Venezuela, simply by his own personal inclinations,” Brew said. “They’re going to need to see it make commercial sense. And right now it simply doesn’t.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Much of the world is once again asking whether fossil fuels are as reliable as they thought — not because power plants are tripping off or wellheads are freezing up, but because terawatts’ worth of energy are currently stuck outside the Strait of Hormuz in oil tankers and liquified natural gas carriers.

The current crisis in many ways echoes the 2022 energy cataclysm, kicked off when Russia invaded Ukraine. Then, oil, gas, and commodity prices immediately spiked across the globe, forcing Europe to reorient its energy supplies away from Russian gas and leaving developing countries in a state of energy poverty as they could not afford to import suddenly dear fuels.

“It just shows once again the risk of being dependent on imported fossil fuels, whether it’s oil, gas, LNG, or coal. It’s an incredibly fragile system that most of the world depends on,” Nick Hedley, an energy transition research analyst at Zero Carbon Analytics, told me. “Most people are at risk from these shocks.”

Countries suddenly competing once again for scarce gas and oil will have to make tough decisions about their energy systems, with consequences for both their economies and the global climate. In the short run, it is likely that many countries will make a dash for energy security and seek to keep their existing systems running, either paying a premium for LNG or turning to coal. In the long run, however, this moment of energy scarcity could provide yet another reason to turn towards renewables and electrification using solar panels and batteries.

The immediate economic risks may be most intense to Iran’s east.

About 90% of LNG from Qatar goes to Asia, with Qatar serving as essentially the sole supplier of LNG to some countries. Even if there’s more LNG available from non-Qatari sources, many poorer Asian countries are likely to lose out to richer countries in Europe or East Asia that can outbid them for the cargoes.

For countries like Pakistan and Bangladesh, “The result is demand destruction, not aggressive spot purchasing,” according to Kpler, the trade analytics service.

LNG supply is “critical” for Asia — roughly a fifth of Asia’s power can be traced back to LNG from the Middle East, Morgan Stanley analysts wrote in a note to clients Thursday.

In its absence, coal usage will likely tick up in the power sector, leading to declining air quality locally and higher emissions of greenhouse gases globally. “For uninterrupted power, coal remains the key alternative to LNG and there is flex capacity available in South Asia, which has seen new coal plants open,” the Morgan Stanley analysts wrote.

In India, the government is considering implementing an emergency directive to coal-fired power plants to “boost generation and to plan fuel procurement to meet peak summer demand,” sources told Argus Media.

Anne-Sophie Corbeau, global research scholar at the Columbia University Center on Global Energy Policy, told me that she does “expect to see some coal switching,” and that she has “already seen an increase in coal prices.” Benchmarks have already risen to their highest level in at least two years, according to the Financial Times.

This likely coal surge comes as two of the world’s most coal-hungry economies — namely India and China — saw their electricity generation from coal power drop in 2025, the first time that’s happened in both countries at once in around 50 years, according to an analysis by Lauri Myllyvirta of the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air. In much of the rich world, by contrast, coal consumption has been falling for decades.

At the same time energy insecurity may tempt countries to stoke their coal fleet, the past few years have also offered examples of huge deployments of solar in some of the countries most affected by high fossil fuel prices, leading some energy analysts to be guardedly optimistic about how the world could respond to the latest energy crisis.

In the developing world especially, the need to import oil for gasoline and natural gas for electricity generation weighs on the terms of trade. Countries become desperate to export goods in exchange for hard currency to pay for essential fuel imports, which are then often subsidized for consumers, weighing on government budgets. But at least for electricity and transportation, there are increasingly alternatives to expensive, imported fossil fuels.

“This is the first oil and gas crisis-slash-pricing scare in which clean alternatives to oil and gas are fully price-competitive,” Isaac Levi, an analyst at CREA, told me. “Looking at the solar booms, we can expect this to boost clean energy deployment in a major way, and that will be the more significant and durable impact.”

The most cited example for this kind of rapid emergency solar uptake is Pakistan, which has experienced one of the fastest solar conversions in history and expects this year to see a fifth of its electricity come from solar, according to the World Resources Institute.

The country was already under pressure from the rising price of energy following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, when it was forced to hike fuel and power prices and cut subsidies as part of a deal with the International Monetary Fund. From 2021 to 2024, Pakistan’s share of generation from solar more than tripled thanks to the growing glut of inexpensive Chinese solar panels that were locked out of the rich world — especially the United States — by tariffs.

“Countries which are heavily dependent on fossil fuel imports are once more feeling very nervous,” Kingsmill Bond, an energy strategist at the clean energy think tank Ember, told me. “The interesting thing is we have two answers: renewables and electrification. If you want quick results, you put solar panels up quickly.”

Other examples of fast transitions have been in transportation, particularly electric cars.

Ethiopia banned the import of internal combustion vehicles due to worries about the high costs of oil imports and fuel subsidies. EVs make up some 8% of the cars on the road in the East African country, up from virtually zero a few years ago. In Asia, Nepal executed a similar push-pull as part of a government effort to reduce both imports and smog; about five years later, over three-quarters of new car sales in the country were electric.

But getting all the ducks in a row for a green transition has proven difficult in both the rich world and the developing world. Few countries have been able to electrify their economies while also powering them cheaply and cleanly. Ethiopia and Nepal are two examples of electrifying demand for power, particularly transportation. But while the two countries are poor compared to much of the world, they are rich in water and elevation, giving them plentiful firm, non-carbon-emitting electricity generation.

Pakistan, on the other hand, is far from being able to, say, synthesize fertilizers at scale with renewable power. In addition to being a power source, natural gas is also a crucial input in industrial fertilizer manufacturing. Faced with spiking costs, fertilizer plants in Pakistan are shutting down, imperiling future food supplies. All the cheap Chinese solar panels and BYD cars in the world can’t feed a chemical plant.

What remains to be seen is whether this crisis will be severe and enduring enough to lead to a fundamental rethinking about the global energy supply — what kind of energy countries want and where they will get it.

“Energy security crises produce the same structural response: the search for sources that do not require crossing borders and global chokepoints,” Jeff Currie, a longtime commodities analyst, and James Stavridis, a retired admiral and NATO’s former Supreme Allied Commander, argued in an analysis for The Carlyle Group. “Solar, wind, and nuclear are children of the 1970s oil shocks — with growth driven by security, not environmentalism.”

While the United States is not unaffected by the unfolding energy crisis — gasoline prices have spiked over $0.25 per gallon in the past week, and diesel prices have spiked $0.40 — its resilience comes from both its domestic oil and gas production and its solar, wind, and nuclear fleets. Much of this electricity generation and power production can be traced back in some respect to those 1970s oil shocks.

In 2024, the United States imported 17% of its primary energy supply, according to the Energy Information Administration, compared to a peak of 34% in 2006 and the lowest since 1985. Today, Asia still imports 35%, and Europe 60%, Bond told me.

“That’s massive levels of dependency in a fragile world,” Bond said. “It’s a question of security.”

On Galvanize’s latest fund strategy and more of the week’s big money moves.

This week brings encouraging news for companies on land and offshore, from the Netherlands to East Africa. First up — and in spite of a federal administration that appears to be actively hostile toward residential and commercial electrification and energy efficiency measures — California gubernatorial candidate Tom Steyer’s investment firm Galvanize just closed a fund devoted to decarbonizing real estate. Elsewhere, we have a Dutch startup pursuing a novel approach to clean heat production, a former Tesla exec rolling out electric motorbikes in East Africa, and an offshore wind developer plans to pair its floating platform with underwater data centers.

With electricity costs on the rise and war in Iran pushing energy prices further upward, energy efficiency measures are looking more prudent — and more profitable — than ever. Amidst this backdrop, the asset manager and venture firm Galvanize announced the close of its first real estate fund, bringing in $370 million as the firm looks to make commercial buildings cleaner and better able to weather price fluctuations in global energy markets.

Galvanize, co-founded by the billionaire Tom Steyer, is already doling out this money, investing in 15 buildings across 11 cities so far. The firm targets real estate in cities where demand is outpacing supply, performing decarbonization upgrades such as installing on-site solar generation and undertaking energy efficiency retrofits such as improved insulation and weatherproof windows.

Galvanize is betting that fluctuations and increases in energy prices will grow faster than the cost of upgrading buildings to be more efficient and lower-emissions, making its strategy profitable in the long-term.

While I’ve long followed thermal battery companies like Rondo and Antora, which use renewable energy to heat up hot rocks capable of delivering industrial heat, I was unaware of iron fuel’s potential to do much the same. That changed this week when the Dutch startup Rift announced it had raised $132 million to commercialize this technology.

The startup produces high-temperature heat by combusting iron powder with ambient air in a specialized boiler engineered to handle metal fuels. This process produces a flame that can reach 2,000 degrees Celsius without emitting any carbon dioxide. The resulting heat can then be delivered as steam, hot water, or hot air to industrial facilities, with the only byproduct being iron oxide (rust), which itself can then be collected and converted back into iron fuel by reacting it with hydrogen produced via low-carbon processes.

Rift’s latest funding comprises a $96.2 million Series B round involving several Netherlands-based investors, along with a $35.5 million grant from the EU Innovation Fund. Both pots of money will support the construction of the company’s first production facility for iron fuel boilers. Rift’s first customer is the building materials manufacturer Kingspan Unidek, with whom it’s developing a project that Rift says will result in over a million metric tons of avoided emissions over a 15-year period.

The electric vehicle transition looks pretty different in East Africa, where two-wheeled motorcycles dominate daily commuting and urban transit. These smaller, lighter vehicles are simple and cheap to electrify, and while their upfront cost is higher than gasoline-powered bikes, operating expenses can be 50% lower. This week, the market received a boost as e-motorbike startup Zeno announced a $25 million Series A round to scale production of its flagship bike.

The round was led by the climate tech VC Congruent Ventures, with support from other heavyweights such as Lowercarbon Capital. Zeno’s CEO Michael Spencer, who left Tesla in 2022 to start the company, sees a larger electrification opportunity in emerging economies than here in the U.S. As he told TechCrunch when Zeno emerged from stealth in fall 2024, “the Tesla master plan has more legs and more room to run with lower hurdles in emerging markets.”

Spencer saw particular potential to sell low-cost motorbikes with batteries that Zeno would own rather than the customer, meaning they can’t charge their bikes at home. Riders instead rely on swap stations where they can exchange depleted batteries for fully charged ones — much as the Chinese electric vehicle company Nio does with its cars.

Zeno designs and manufactures its own bikes and charging infrastructure, with 800 motorbikes sold and 150 charging and battery-swap stations installed across four cities across Kenya and Uganda. With this latest influx of cash, the company plans to fulfill its backlogged orderbook, which it says now has more than 25,000 retail and fleet customers.

Data centers developers are hitting bottlenecks securing energy, land, and social acceptance — so the startup Aikido wants to ship them out to sea, where it says “energy, cooling and space are abundant.” This week, the offshore wind developer revealed its novel floating turbine platform, designed to co-locate wind generation and battery storage with data centers submerged in compartments connected to the turbine itself.

The installation would still be grid-connected, but the idea is that the turbine and batteries will meet most of the data center’s energy needs, drawing on the grid mainly during the summer when the wind dies down. A 100-kilowatt proof of concept is already being developed in Norway, with the first commercial deployment slated for the U.K. sometime in 2028. Eventually, Aikido says it envisions building “gigawatt-scale” data centers at sea — an ambitious undertaking in a notoriously harsh environment.

But as CEO Sam Kanner reasoned in a press release, “before we go off-world, we should go offshore” — a likely jab at Elon Musk, who has repeatedly expressed his desire to launch data centers into space to rid himself of terrestrial concerns over real estate and energy.

A conversation with Center for Rural Innovation founder and Vermont hative Matt Dunne.

This week’s conversation is with Matt Dunne, founder of the nonprofit Center for Rural Innovation, which focuses on technology, social responsibility, and empowering small, economically depressed communities.

Dunne was born and raised in Vermont, where he still lives today. He was a state legislator in the Green Mountain State for many years. I first became familiar with his name when I was in college at the state’s public university, reporting on his candidacy for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination in 2016. Dunne ultimately lost a tight race to Sue Minter, who then lost to current governor Phil Scott, a Republican.

I can still remember how back in 2016, Dunne’s politics then presaged the kind of rural empathy and economic populism now en vogue and rising within the Democratic Party. Dunne endorsed Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential bid and was backed by the state’s AFL-CIO; Minter, a more establishment Democrat, stayed out of the 2016 primary and underperformed in the general election. It doesn’t surprise me now to see Dunne emerging with novel, nuanced perspectives on how advanced technological infrastructure can succeed in rural America. So I decided to chat with him about the state of data center development today.

The following chat has been lightly edited for clarity.

So first of all, can you tell our readers about your organization in case they’re unfamiliar?

We founded this social enterprise back in 2017 because the economic gap between urban and rural turned into a chasm. We traced the core reasons and it was the winners and losers of the tech economy. There were millions and millions of jobs created from the great recession, but the problem was that it was almost exclusively in urban areas, in the services sectors like consulting, finance, and tech. At the end of the day, we believe in the age of the internet there should be no limit to where high-quality technology jobs should thrive.

We work with communities across the country that are rural and looking to add technology as a component to their economy. We help them with strategies – tech accelerators, tech accountability programs, co-working spaces, all the other stuff you need to create a vibrant place where those kinds of companies can emerge so people can come back, come home. We work with 43 regions across 25 states that are all on this journey together and help them secure the resources to execute on that journey.

One of the reasons I wanted to speak with you is your history in Vermont. I went to the University of Vermont, and I loved living there, but there aren’t jobs to keep kids there which is still a huge disappointment to young folks who love living in the state.

At the same time the state reflects many of the same signals we see in Heatmap Pro data around advanced industrial development. Large land owners bristle at new projects regardless of their political party, and Democratic voters are more inclined to side more with locavorism than a YIMBY growth-minded approach.

How do your Vermonter roots inform your work, and do they affect the ways you see the conflicts over new advanced tech infrastructure?

What we’ve seen in Vermont after the Great Recession is that there’s lots of available space and a population that’s aged significantly.

This all impacted my outlook as a community development person, and now as a leader of a social enterprise. We need to be thinking proactively about what an economically healthy community looks like and how we ensure we have places importing cash and exporting value in a way that doesn’t destroy what’s amazing about these rural places. You pretty quickly land on tech, as well as maybe some design-related manufacturing where the ideas are local.

To make it clear, we’re building infrastructure for technology communities which is different from building technology infrastructure itself. That’s an important distinction. It’s about giving them the tools to stand up a tech accelerator and have a co-working space that creates community. A good co-working space has good programming, allows for remote workers to go to a place, and you can have those virtuous collisions that lead to something else. A collaboration. A volunteer project. Whatever it is. Having hack-a-thons, lectures or demonstrations on the latest AI technology that can be used. Youth programming around robotics. If you can create a space where that happens, you create a lot of synergy, which is important in smaller markets – you have to be intentional with all of this.

Okay, so considering those practices, what do you think of the way data center development is going?

For the record, I spent six and a half years at Google and was hired at first because of data centers. At the time, I saw Google try to build a big data center in a community of less than 10,000 people in secret, and it didn’t go well because it just doesn’t work, and that’s how I got my job there.

There is a right way to come into a community with a data center or frankly any kind of global company infrastructure project, and there’s a wrong way to do it. The right way is being as transparent as possible, knowing full well that when a brand name is mentioned, the price goes through the roof for the land. There does have to be some level of confidentiality when you’re ready to go, but once you can, you have to be proactive with it.

You have to be a really good steward on the impacts, whether they’re electrical demand or water demand. It’s about being clear, it’s about figuring out how to mitigate it, and it’s about maintaining your commitment to 100% renewable energy even as you’re bringing online data centers. Oh, and it’s about having a real financial commitment to make sure the community can economically diversify away from being overly dependent on the data center, on that one industry. The data center developers know full well that they’ll create a lot of construction jobs but that’s not going to be a good, sustainable employer. Frankly, the history of rural places is littered with communities that are too dependent on one industry, one company, and that hasn’t

What does that look like from a policy perspective and a community relations perspective?

I think there are models emerging, including from Microsoft, Google, and others, about what good entry and strong commitments look like. It would be great if someone put a line in the sand about 2% of capex going to a community to diversify the economy. It would be great if companies put a reasonable time horizon out there to replace potable water through technology or other kinds of supports. It would be great to see commitments to ratepayers that say people won’t have to foot the bill for increased demand.

Here’s the part we focus on more because we’re not as focused on site selection: Rural America is likely to shoulder the burden of data center infrastructure just like they shouldered the burden of energy production infrastructure. The question at the end of the day is, how do we make sure those communities see the upside? How do we make sure they can leverage tech capacity inside these data centers to be able to have more agency and chart their own economic futures? That’s what we’re really focused on because if you do that, it doesn’t have to be a repeat of the extractive processes of the past, where rural places were used for cheap land and low-wage workers. They can instead be places with lots of land available and incredible innovation, new enterprises and solving the world’s problems.