You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Why Patagonia, REI, and just about every other gear retailer are going PFAS-free.

Hiking gear exists so that, when nature tries to kill you, it is a little less likely to succeed. Sometimes this gear’s life-saving function is obvious — a Nalgene to carry extra water so you don’t die of thirst, or a fist-sized first-aid kit so you don’t bleed to death — while other things you don’t necessarily purchase with the thought that they might one day save your life. Like, say, a small Swiss Army Knife. Or, in my case, a raincoat.

Last summer, on a casual day hike in Mount Rainier National Park, my family was overtaken by a storm that, quite literally, rose up out of nowhere. It had been a sunny, clear day when we left the parking lot; at four miles in, we were being lashed by hail and gale-force winds on an exposed alpine trail, with no trees or boulders nearby for shelter.

Then, one member of our hiking party tripped.

In the split second before she stood up and confirmed she could walk out on her own, my mind raced through what I had in my pack. Stupidly, I had nothing to assemble a makeshift shelter, no warmer layers. But I did have my blue waterproof rainshell. In weather as extreme as the storm off Rainier that day, keeping dry is essential; if we’d had to wait out the rain due to a broken ankle, we’d have become soaked and hypothermic long before help arrived. My raincoat, I realized during those terrifying seconds, could save my life.

But what made my raincoat so trustworthy that day on the mountain could also, in theory, kill me — or, more likely, kill or sicken any of the thousands of people who live downstream of the manufacturers that make waterproofing chemicals and the landfills where waterproof clothing is incinerated or interred. Outdoor apparel is typically ultraprocessed and treated using perfluoroalkyl and poly-fluoroalkyl substances, a class of water- and stain-resistant “forever chemicals” that are more commonly referred to as PFAS (pronounced “pee-fass”). After decades of work by environmental groups and health advocates, states and retailers are finally banning the sale of textiles that have been treated with the chemicals, which in the outdoor industry often manifest in the form of Gore-Tex membranes or “durable water repellent” treatments.

These bans are fast approaching: Beginning in 2025 — less than 12 months from now — California will forbid the sale of most PFAS-treated textiles; New York will restrict them in apparel; and Washington will regulate stain- and waterproofing treatments, with similar regulations pending or approved in a number of other states. Following pressure from activists, the nation’s largest outdoor retailer, REI, also announced last winter that it will ban PFAS in all the textile products and cookware sold in its stores starting fall 2024; Dick’s Sporting Goods will also eliminate PFAS from its brand-name clothing.

This will upend the outdoor apparel industry. Some of the best coats in the world — legendary gear like Arc’teryx’s Beta AR and the traditional construction of the Patagonia Torrentshell — use, or until recently used, PFAS in their waterproofing processes or in their jackets’ physical membranes. Though the bans frequently allow vague, temporary loopholes for gear intended for “extreme wet conditions” or “expeditions,” such exceptions will be closed off by the end of the 2020s. (Patagonia has “committed to making all membranes and water-repellent finishes without [PFAS] by 2025,” Gin Ando, a spokesperson for the company, told me; Arc’teryx spokesperson Amy May shared that the company is “committed to moving towards PFAS-free materials in its products.”)

Even if you aren’t buying expedition-level gear, your closet almost certainly contains PFAS. A 2022 study by Toxic-Free Future found the chemicals in nearly 75% of products labeled as waterproof or stain-resistant. Another study found that the concentration of fluorotelomer alcohols, which are used in the production of PFAS, was 30 times higher inside stores that sold outdoor clothing than in other workplaces.

Get one great climate story in your inbox every day:

The reason outdoor companies have historically loved PFAS so much is simple: The chemicals are unrivaled in their water repellency. PFAS are manufactured chains of fluorine-carbon bonds that are incredibly difficult to break (the precise number of carbons is also used in the naming process, which is why you’ll hear them called “C8” or “C6,” sometimes, as well). Because of this strong bond, other molecules slip off when they come into contact with the fluorine-carbon chain; you can observe this in a DIY test at home by dripping water onto a fabric and watching it roll off, leaving your garment perfectly dry.

It is also because of this bond that PFAS are so stubbornly persistent — in the environment, certainly, but also in us. An estimated 98% to 99% of people have traces of PFAS in their bodies. Researchers have found the molecules in breast milk, rainwater, and Antarctica’s snow. We inhale them in dust and drink them in our tap water, and because they look a little like a fatty acid to our bodies, they can cause health problems that we’re only beginning to grasp. So far, PFAS have been linked to kidney and testicular cancer, decreased fertility, elevated cholesterol, weight gain, thyroid disease, the pregnancy complication pre-eclampsia, increased risk of preterm birth and low birth weight, hormone interference, and reduced vaccine response in children.

Chemical companies and industry groups often argue that certain PFAS are demonstrably worse than others; the so-called “long-chain” molecules, for instance, are thought to have higher bioaccumulation and toxicity potential, and have mostly been replaced by “short-chain” molecules. But as Arlene Blum, a pioneering mountaineer and the founder of the Green Science Policy Institute, an environmental advocacy organization that opposes PFAS, told me, “in all the cases that we’ve studied,” forever chemicals have been found “to be harmful in one way or another,” whether they’re short or long.

From a health perspective, the good news is that activists are winning. While initial efforts to protect humans and the environment from PFAS in the mid-2000s resulted only in the voluntary phase-out of long-chain chemicals like PFOA and PFOS, the new laws target the entire class of thousands of compounds to prevent an ongoing game of whack-a-mole with chemical manufacturers. (A recent report by The Guardian found that the chemical industry spent $110 million in the last two U.S. election cycles trying to thwart or slow the various bans.) Public pressure campaigns mounted against ostensibly sustainability-minded companies like REI have prompted store-initiated PFAS bans that will also influence future gear sold in the United States. (REI was long a PFAS laggard, and was even hit in 2022 with a class-action lawsuit over allegedly marketing PFAS-containing clothes as “sustainable.” The company declined to comment for this story. Dick’s Sporting Goods did not respond to requests for comment.)

But as the days tick closer to the first PFAS bans coming into effect in stores this fall, outdoor apparel companies are still scrambling to redesign their clothing. Some alternatives to PFAS do exist — Blum swears by her PFAS-free Black Diamond jacket — though even the most ardent supporters of the forever chemical bans will admit the waterproofing alternatives haven’t 100% caught up yet.

“The main concern that most people have in the industry is the amount of work that it’s going to take to meet these guidelines,” Chris Steinkamp, the head of advocacy at the trade association Snowsports Industries America, told me. “Because PFAS is omnipresent. Unfortunately, they’re pretty much in everything.”

Many outdoor apparel companies genuinely want to comply with the coming bans, Karolína Brabcová, the campaign manager for toxic chemicals in consumer products at Arnika, a Czech environmental non-profit, told me. “It’s not such a matter of greenwashing here,” she said. “It’s more about the fact that you’ve got the chemical industry on one side and the downstream users joining the consumers on the other side. And the downstream users don’t know everywhere the PFAS are being used; it’s a business secret.”

In one case detailed by Bloomberg, the Swedish company Fjällräven had stopped using PFAS in its products, only to learn from a 2012 Greenpeace investigation that the chemicals were still present in its apparel. “A supplier using fluorochemistry on another company’s products was cross-contaminating Fjällräven’s,” the Bloomberg authors write, adding that “subsequent testing revealed” just having “products in stores near products from other companies that used the chemicals still resulted in low levels of contamination.”

It isn’t always the case, however, that clothing manufacturers are unwitting victims of chemical sloppiness. Some apparel companies have taken advantage of the alphabet soup of chemical names to look more sustainable than they are. “We’ve seen in recent years products labeled as ‘PFOA-free’ or ‘PFOS-free,’ which suggests that they do not contain the long-chain PFAS that have largely been phased out from production in the United States,” Blum warned me. “That’s really misleading because oftentimes it’s a signal a product likely contains other PFAS chemicals, which may be just as persistent and may also be quite toxic in production to disposal.”

The reason I could count on my raincoat to protect me in the mountains, though, was because, like most expedition-level gear, it is made of a membrane manufactured by Gore-Tex, with an additional DWR waterproofing finish that also contains PFAS. Gore-Tex is known in the outdoors industry for making the holy grail of performance fabrics: Its membranes are waterproof, durable, and breathable enough to exercise in, a challenging and impressive combination to nail. But to achieve this, the company has traditionally used the fluoropolymer PTFE, a notorious forever chemical you probably know by the trademarked name Teflon.

This technology — or rather, these chemicals — are incredibly and irresistibly good at what they do. “The terrible truth,” Wired wrote in its list of raincoat recommendations updated this past December, “is that if you’re going to be exposed [to inclement weather] for multiple hours, you are probably not going to be able to rely on a [PFAS]-free DWR to keep hypothermia at bay.”

When I reached out to Gore-Tex about its use of PFAS, company spokesperson Julie Evans told me via email that “there are important distinctions among materials associated with the term PFAS” and that the fluoropolymers Gore uses, such as PTFE, “are not the same as those substances that are bioavailable, mobile, and persistent.” She stressed that “not all PFAS are the same” and that PTFE and the other fluoropolymers in the Gore arsenal meet the standards of low concern, and are “extremely stable and do not degrade in the environment,” are “too large to be bioavailable,” and are “non-toxic [and] safe to use from an environmental and human perspective.” The National Resource Defense Council, by contrast, writes that PFAS polymers like PTFE, “when added as a coating or membrane to a raincoat or other product, can pose a toxic risk to wearers, just as other PFAS can.”

Some of the environmental health advocates I spoke with said Gore-Tex’s language was misleading. Mike Schade, the director of Toxic-Free Future’s Mind the Store program, which pressures retailers to avoid stocking items that use hazardous chemicals, told me that while it is “laudable that the company has phased some PFAS out of their products … what we’re concerned about is the entire class. We think it’s misleading to consumers and to the public to suggest that other PFAS are not of environmental concern.”

Blum, of the Green Science Policy Institute, admitted that while “probably your Gore-Tex jacket won’t hurt you” — there is limited evidence that PFAS will leech into your body just from wearing it — there’s a more significant issue at the heart of the PFAS debate. “When you go from the monomer to the polymer” in the chemical manufacturing process, she said, it “contaminates the drinking water in the area where it’s made.” The disposal process — and especially incineration, a common fate for discarded clothing — is another opportunity for PFAS to shed into the environment. People who live near landfills and chemical manufacturing plants in industrial hubs like Michigan and many cities in Bangladesh suffer from PFAS at disproportionate levels.

So then, where do we go from here? Hikers, skiers, mountaineers, fly-fishers — they all still need clothing to stay dry. “Our industry is committed to performance and making sure that the gear that people are sold can live up to the standards that athletes need,” Steinkamp said. “I know that is top of mind, and that’s what’s making [the transition] so hard.”

But it also might be the case that our gear is too waterproof. “When we think about the intended performance of outdoor gear, there’s a lot of expectation that your gear will keep you extremely dry,” Kaytlin Moeller, the regional sustainability manager at Fenix Outdoor North America, the parent company of outdoors brands like Fjällräven and Royal Robbins, told me. “But when we really start to look at it,” she added, “I think part of the question is: What is the level of functionality that is really necessary for the customer to have a positive experience outdoors and be prepared for their adventure?”

It’s probably less than you think; consumers frequently don Everest-level technologies to walk their dogs for 15 minutes in a drizzle. “As responsible creators of products, it’s our job to balance functionality with impact,” Moeller said. “And in terms of [PFAS], it just wasn’t worth the risk and the carcinogenic qualities to continue putting that treatment on our products when there are other innovative coatings and constructions that we can use.”

Those alternatives, like innovative fabric weavings and proprietary waxes, might not sound as high-tech as hydrophobic chemicals. Still, for the vast majority of regular people — and even most outdoor recreators — it’s likely more than enough to stay comfortably dry. “We’ve been going into the outdoors for hundreds and hundreds of years without these chemicals,” Schade pointed out. “We can do it again.”

Luckily for everything and everyone on the planet, new waterproofing products are getting better by the day. Gore-Tex has spent “the better part of the last decade” developing its new PFAS-free “ePE membrane,” Evans told me. Short for expanded polyethylene, ePE is fluorine-free (albeit, derived from fossil fuels) and has been adopted by Patagonia, Arc’teryx, and others in the outdoor industry as a PFAS-free alternative. Evans described it as feeling “a little lighter and softer” than old-school Gore-Tex, but “with all the same level of performance benefits” as the historic products.

Other companies, including Patagonia, have been transparent about their phase-out goals and the ongoing difficulties of the PFAS-free transition; Gin, the Patagonia spokesperson, told me that as of this fall, “92% of our materials by volume with water-repellent chemistries are made without” PFAS, and that the new waterproofing “stands up to the demands of our most technical items.” Deuter, Black Diamond, Outdoor Research, Jack Wolfskin, Mammut, Marmot, and prAna are among other outdoor brands that are working to remove PFAS from their gear.

“We have to work together, collaboratively, if we really want to eliminate them — to the point of the verbiage around being [PFAS]-free,” Moeller stressed. “No one can be [PFAS]-free ‘til everyone in the industry is, because of the risk of cross-contamination.”

Then there are the consumers who will need to adjust. I admit, in the weeks before beginning the reporting for this article, I bought myself another raincoat. It was on sale from one of my favorite outdoor brands, and I was attracted to its aggressively cheerful shade of Morton Salt-girl yellow, which I thought would also help me stand out in the case of a future emergency.

At the time, I hadn’t even thought to check what it was made of; what mattered to me was how, when I slipped it on, I became amphibious — like some kind of marine mammal, slick and impervious to the rain. Stepping out of my front door and into a downpour, I felt practically invincible.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

On a new report from the Energy Institute, high-stakes legislating, and accelerating nuclear development

Current conditions: Monsoon rains hit the southwestern U.S., with flash floods in Roswell, New Mexico, and flooding in El Paso, Texas • The Forsyth Fire in Utah has spread to 9,000 acres and is only 5% contained • While temperatures are falling into the low 80s in much of the Northeast, a high of 96 degrees Fahrenheit is forecast for Washington, D.C., where Republicans in the Senate seek to finish their work on the “One Big, Beautiful Bill.”

The world used more of just about every kind of energy source in 2024, including coal, oil, gas, renewables, hydro, and nuclear, according to the annual Statistical Review of World Energy, released by the Energy Institute. Here are some of the key numbers from the report:

You can read the full report here.

Virginia Republican Jen Kiggans is a vice chair of the Conservative Climate Caucus and a signatory of several letters supporting the preservation of clean energy tax credits in the Inflation Reduction Act, including one letter she co-authored with Pennsylvania’s Brian Fitzpatrick criticizing the House reconciliation bill’s rough approach to slashing the credits. On Wednesday, however, she said on X that the Senate language “responsibly phases out certain tax credits while preserving American investment and innovation in our energy sector.”

The Senate is still pushing to have the reconciliation bill on President Trump’s desk by July 4, and is expected to work through the weekend to get it done. But as Sahil Kapur of NBC News reported Wednesday, House and Senate leaders have been attempting to hash out yet another version of the bill that could pass both chambers quickly, meaning the legislation is still very much in flux.

Shell is in early talks to acquire fellow multinational oil giant BP, the Wall Street Journal reported. While BP declined to comment to the Journal, Shell called the story “market speculation” and said that “no talks are taking place.”

BP is currently valued at $80 billion, which would make a potential tie-up the largest corporate oil deal since the Exxon Mobil merger, according to the Journal.

Both Shell and BP have walked back from commitments to and investments in decarbonization and green energy in recent months. BP said in September of last year that it would divest from its U.S. wind business, while Shell said in January that it would “pause” its investment in the U.S. offshore wind industry and took an accompanying charge of $1 billion.

The combined company would be better positioned to compete with supermajors like Exxon, which is now worth over $450 billion, while Shell and BP have a combined valuation around $285 billion.

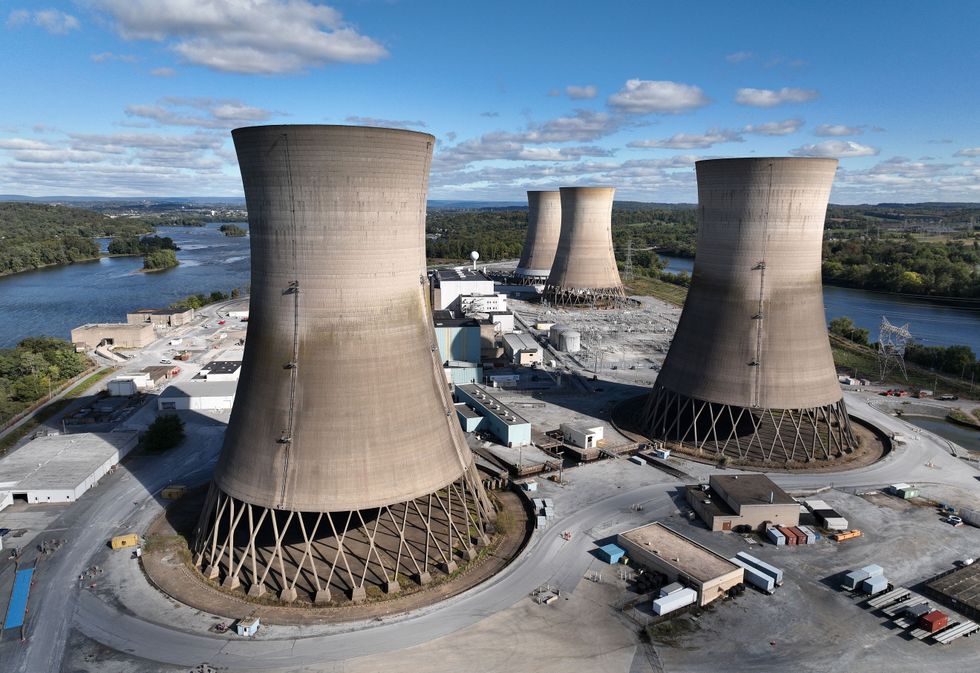

Three Mile Island Unit 1 will restart a year early, its owner Constellation said Wednesday. When Constellation and Microsoft announced the plan to restart the nuclear facility last fall they gave a target date of 2028. More recently, however, PJM Interconnection, the interstate electricity market that includes Pennsylvania, approved a request made from the state’s governor, Josh Shapiro, to fast-track the plant’s interconnection, the company said, meaning it could open as soon as 2027.

Constellation reported “significant progress” on hiring and training new workers, with around 400 workers either hired or due to start new jobs soon. “We’re on track to make history ahead of schedule, helping America achieve energy independence, supercharge economic growth, and win the global AI race,” Constellation’s chief executive Joe Dominguez said.

The Chinese electric carmarker BYD is addressing rising inventory and lower prices by cutting back its production plans. The company “has slowed its production and expansion pace in recent months by reducing shifts at some factories in China and delaying plans to add new production lines,” Reuters reported.

The slowdown comes “as it grapples with rising inventory even after offering deep price cuts in China's cutthroat auto market,” according to the Reuters report.

In 2024, BYD beat out Tesla in annual sales, with over 4 million cars sold, for a total annual revenue over $100 billion. Tesla’s revenue was just short of $100 billion last year.

While BYD’s factories may be slowing down, it is still looking to expand, especially overseas. In April, more than 7,000 BYD battery electric cars were registered in Europe, according to Bloomberg. This more-than-doubling since last year slingshotted BYD past Tesla on the continent, where its sales have fallen by almost 50%.

“Where does the power sector go from here?” an audience member asked at our exclusive Heatmap subscriber event in New York on Wednesday, referring to a potential future without the Inflation Reduction Act. “Higher costs,” Emily Pontecorvo answered. There is one potential bright spot, however, as Robinson Meyer explained: “If I were a Democrat considering running an affordability campaign or a cost-of-living campaign in ’26 or ’28, there’s lots of openings to talk about clean energy — the policy that’s happening right now — utility rates, and energy affordability.”

The science is still out — but some of the industry’s key players are moving ahead regardless.

The ocean is by far the world’s largest carbon sink, capturing about 30% of human-caused CO2 emissions and about 90% of the excess heat energy from said emissions. For about as long as scientists have known these numbers, there’s been intrigue around engineering the ocean to absorb even more. And more recently, a few startups have gotten closer to making this a reality.

Last week, one of them got a vote of confidence from leading carbon removal registry Isometric, which for the first time validated “ocean alkalinity enhancement” credits sold by the startup Planetary — 625.6 to be exact, representing 625.6 metric tons of carbon removed. No other registry has issued credits for this type of carbon removal.

When the ocean absorbs carbon, the CO2 in the air reacts with the water to form carbonic acid, which quickly breaks down into hydrogen ions and bicarbonate. The excess hydrogen increases the acidity of the ocean, changing its chemistry to make it less effective at absorbing CO2, like a sponge that’s already damp. As levels of atmospheric CO2 increase, the ocean is getting more acidic overall, threatening marine ecosystems.

Planetary is working to make the ocean less acidic, so that it can take in more carbon. At its pilot plant in Nova Scotia, the company adds alkalizing magnesium hydroxide to wastewater after it’s been used to cool a coastal power plant and before it’s discharged back into the ocean. When the alkaline substance (which, if you remember your high school chemistry, is also known as a base) dissolves in the water, it releases hydroxide ions, which combine with and neutralize hydrogen ions. This in turn reduces local acidity and raises the ocean’s pH, thus increasing its capacity to absorb more carbon dioxide. That CO2 is then stored as a stable bicarbonate for thousands of years.

“The ocean has just got such a vast amount of capacity to store carbon within it,” Will Burt, Planetary’s vice president of science and product, told me. Because ocean alkalinity enhancement mimics a natural process, there are fewer ecosystem concerns than with some other means of ocean-based carbon removal, such as stimulating algae blooms. And unlike biomass or soil-related carbon removal methods, it has a very minimal land footprint. For this reason, Burt told me “the massiveness of the ocean is going to be the key to climate relevance” for the carbon dioxide removal industry as a whole.

But that’s no guarantee. As with any open system where carbon can flow in and out, how much carbon the ocean actually absorbs is tricky to measure and verify. The best oceanography models we have still don’t always align with observational data.

Given this, is it too soon for Planetary to issue credits? It’s just not possible right now for the startup — or anyone in the field — to quantify the exact amount of carbon that this process is removing. And while the company incorporates error bars into its calculations and crediting mechanisms, scientists simply aren’t certain about the degree of uncertainty that remains.

“I think we still have a lot of work to do to actually characterize the uncertainty bars and make ourselves confident that there aren’t unknown unknowns that we are not thinking about,” Freya Chay, a program lead at CarbonPlan, told me. The nonprofit aims to analyze the efficacy of various carbon removal pathways, and has worked with Planetary to evaluate and inform its approach to ocean alkalinity enhancement.

Planetary’s process for measurement and verification employs a combination of near field observational data and extensive ocean modeling to estimate the rate, efficiency, and permanence of carbon uptake. Close to the point where it releases the magnesium hydroxide, the company uses autonomous sensors at and below the ocean’s surface to measure pH and other variables. This real-time data then feeds into ocean models intended to simulate large-scale processes such as how alkalinity disperses and dissolves, the dynamics of CO2 absorption, and ultimately how much carbon is locked away for the long-term.

But though Planetary’s models are peer-reviewed and best in class, they have their limits. One of the largest remaining unknowns is how natural changes in ocean alkalinity feed into the whole equation — that is, it’s possible that artificially alkalizing the ocean could prevent the uptake of naturally occurring bases. If this is happening at scale, it would call into question the “enhancement” part of alkalinity enhancement.

There’s also the issue of regional and seasonal variability in the efficiency of CO2 uptake, which makes it difficult to put any hard numbers to the efficacy of this solution overall. To this end, CarbonPlan has worked with the marine carbon removal research organization [C]Worthy to develop an interactive tool that allows companies to explore how alkalinity moves through the ocean and removes carbon in various regions over time.

As Chay explained, though, not all the models agree on just how much carbon is removed by a given base in a given location at a given time. “You can characterize how different the models are from each other, but then you also have to figure out which ones best represent the real world,” she told me. “And I think we have a lot of work to do on that front.”

From Chay’s perspective, whether or not Planetary is “ready” to start selling carbon removal credits largely depends on the claims that its buyers are trying to make. One way to think about it, she told me, is to imagine how these credits would stand up in a hypothetical compliance carbon market, in which a polluter could buy a certain amount of ocean alkalinity credits that would then allow them to release an equivalent amount of emissions under a legally mandated cap.

“When I think about that, I have a very clear instinctual reaction, which is, No, we are far from ready,”Chay told me.

Of course, we don’t live in a world with a compliance carbon market, and most of Planetary’s customers thus far — Stripe, Shopify, and the larger carbon removal coalition, Frontier, that they’re members of — have refrained from making concrete claims about how their voluntary carbon removal purchases impact broader emissions goals. But another customer, British Airways, does appear to tout its purchases from Planetary and others as one of many pathways it’s pursuing to reach net zero. Much like the carbon market itself, such claims are not formally regulated.

All of this, Chay told me, makes trying to discern the most responsible way to support nascent solutions all the more “squishy.”

Matt Long, CEO and co-founder of [C]Worthy, told me that he thinks it’s both appropriate and important to start issuing credits for ocean alkalinity enhancement — while also acknowledging that “we have robust reason to believe that we can do a lot better” when it comes to assessing these removals.

For the time being, he calls Planetary’s approach to measurement “largely credible.”

“What we need to adopt is a permissive stance towards uncertainty in the early days, such that the industry can get off the ground and we can leverage commercial pilot deployments, like the one that Planetary has engaged in, as opportunities to advance the science and practice of removal quantification,” Long told me.

Indeed, for these early-stage removal technologies there are virtually no other viable paths to market beyond selling credits on the voluntary market. This, of course, is the very raison d’etre of the Frontier coalition, which was formed to help emerging CO2 removal technologies by pre-purchasing significant quantities of carbon removal. Today’s investors are banking on the hope that one day, the federal government will establish a domestic compliance market that allows companies to offset emissions by purchasing removal credits. But until then, there’s not really a pool of buyers willing to fund no-strings-attached CO2 removal.

Isometric — an early-stage startup itself — says its goal is to restore trust in the voluntary carbon market, which has a history of issuing bogus offset credits. By contrast, Isometric only issues “carbon removal” credits, which — unlike offsets — are intended to represent a permanent drawdown of CO2 from the atmosphere, which the company defines as 1,000 years or longer. Isometric’s credits also must align with the registry’s peer-reviewed carbon removal protocols, though these are often written in collaboration with startups such as Planetary that are looking to get their methodologies approved.

The initial carbon removal methods that Isometric dove into — bio-oil geological storage, biomass geological storage, direct air capture — are very measurable. But Isometric has since branched beyond the easy wins to develop protocols for potentially less permanent and more difficult to quantify carbon removal methods, including enhanced weathering, biochar production, and reforestation.

Thus, the core tension remains. Because while Isometric’s website boasts that corporations can “be confident every credit is a guaranteed tonne of carbon removal,” the way researchers like Chay and Long talk about Planetary makes it sound much more like a promising science project that’s being refined and iterated upon in the public sphere.

For his part, Burt told me he knows that Planetary’s current methodologies have room for improvement, and that being transparent about that is what will ultimately move the company forward. “I am constantly talking to oceanography forums about, Here’s how we’re doing it. We know it’s not perfect. How do we improve it?” he said.

While Planetary wouldn’t reveal its current price per ton of CO2 removed, the company told me in an emailed statement that it expects its approach “to ultimately be the lowest-cost form” of carbon removal. Burt said that today, the majority of a credit’s cost — and its embedded emissions — comes from transporting bases from the company’s current source in Spain to its pilot project in Nova Scotia. In the future, the startup plans to mitigate this by co-locating its projects and alkalinity sources, and by clustering project sites in the same area.

“You could probably have another one of these sites 2 kilometers down the coast,” he told me, referring to the Nova Scotia project. “You could do another 100,000 tonnes there, and that would not be too much for the system, because the ocean is very quickly diluted.”

The company has a long way to go before reaching that type of scale though. From the latter half of last year until now, Planetary has released about 1,100 metric tons of material into the ocean, which it says will lead to about 1,000 metric tons of carbon removal.

But as I was reminded by everyone, we’re still in the first inning of the ocean alkalinity enhancement era. For its part, [C]Worthy is now working to create the data and modeling infrastructure that startups such as Planetary will one day use to more precisely quantify their carbon removal benefits.

“We do not have the system in place that we will have. But as a community, we have to recognize the requirement for carbon removal is very large, and that the implication is that we need to be building this industry now,” Long told me.

In other words: Ready or not, here we come.

On mercury rising, climate finance, and aviation emissions

Current conditions: Tropical Storm Andrea has become the first named Atlantic storm of 2025 • Hundreds of thousands are fleeing their homes in southwest China as heavy rains cause rivers to overflow • It’s hot and humid in New York’s Long Island City neighborhood, where last night New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani delivered his victory speech after defeating former governor and longtime party power broker Andrew Cuomo in the race’s Democratic primary.

The brutal heat dome baking the eastern half of the United States continues today. Cooler weather is in the forecast for tomorrow, but this heat wave has broken a slew of temperature records across multiple states this week:

In Washington, D.C., rail temperatures reached a blistering 135 degrees, forcing the city’s Metro to slow down train service. Meanwhile, in New Jersey, the heat sickened more than 150 people attending a high school graduation ceremony. As power demand surged, the Department of Energy issued an energy emergency in the Southeast to “help mitigate the risk of blackouts.”

As Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin pointed out on Tuesday, in terms of what is on the grid and what is demanded of it, this may be the easiest summer for a long time. “Demands on the grid are growing at the same time the resources powering it are changing,” Zeitlin writes. “Electricity load growth is forecast to grow several percent a year through at least the end of the decade. At the same time, aging plants reliant on oil, gas, and coal are being retired (although planned retirements are slowing down), while new resources, largely solar and batteries, are often stuck in long interconnection queues — and, when they do come online, offer unique challenges to grid operators when demand is high.”

A group of 21 Democrat-led states including New Jersey, Massachusetts, New York, Arizona, and California, is suing the Trump administration for cutting billions of dollars in federal funding, including grants related to climate change initiatives. The lawsuit says federal agencies have been “unlawfully invoking a single subclause” to cancel grants that the administration deems no longer align with its priorities. The clause in question states that federal agencies can terminate grants “pursuant to the terms and conditions of the federal award, including, to the extent authorized by law, if an award no longer effectuates the program goals or agency priorities.” The states accuse the administration of leaning on this clause for “virtually unfettered authority to withhold federal funding any time they no longer wish to support the programs for which Congress has appropriated funding.”

The rollback has gutted projects across states and nonprofits that support diversity, equity, and inclusion, as well as climate change preparation programs and research. The states say the clause is being used unlawfully, and hope a judge agrees. “These cuts are simply illegal,” said New York Attorney General Letitia James. “Congress has the power of the purse, and the president cannot cut billions of dollars of essential resources simply because he doesn’t like the programs being funded.”

Get Heatmap AM directly in your inbox every morning:

A brief update from the Bonn Climate Change Conference in Germany: A group of 44 “Least Developed Countries” have called for rich countries to triple the financing goal for climate change adaptation by 2030 compared to 2022 levels. The current target sits at $40 billion a year by 2025, a number set back in 2021 at COP26. According toClimate Home News, tripling the financing goal on 2022 levels would bring in a little less than $100 billion annually. That’s far short of the $160 billion to $340 billion that the United Nations estimates will be needed by 2030. The Indian Express also reports that developing countries have “managed to force a reopening of discussions on the obligations of developed nations to ‘provide’ finance, and not just make efforts towards ‘mobilising’ financial resources, for climate action.” The issue will also be discussed at COP30 in Brazil later this year. The Bonn conference has been running since June 16 and ends tomorrow.

In the UK, aviation is now a bigger source of greenhouse gas emissions than the power sector, according to a new report from the Climate Change Committee. The independent climate advisors say that demand for leisure travel is boosting demand for international flights, and “continued emissions growth in this sector could put future targets at risk.” Meanwhile, the UK power sector has been rapidly decarbonizing, and is now the sixth largest source of emissions. (In the U.S., electricity production is the second-largest source of emissions, behind transportation.) The report also found that heat pump installations increased by 56% in 2024, and that nearly 20% of new vehicles sold were electric. UK emissions were down 50% last year compared to 1990.

The committee applauded the progress but urged more action from the government to cut electricity prices to help speed up the transition to clean technologies. “Our country is among a leading group of economies demonstrating a commitment to decarbonise society,” said Piers Forster, interim chair of the committee. “This is to be celebrated: delivering deep emissions reduction is the only way to slow global warming.”

Voters in North Carolina want Congress to leave the Inflation Reduction Act well enough alone, a new poll from Data for Progress finds. The survey, which asked North Carolina voters specifically about the clean energy and climate provisions in the bill, presented respondents with a choice between two statements: “The IRA should be repealed by Congress” and “The IRA should be kept in place by Congress.” (“Don’t know” was also an option.) The responses from voters broke down predictably along party lines, with 71% of Democrats preferring to keep the IRA in place compared to just 31% of Republicans, with half of independent voters in favor of keeping the climate law. Overall, half of North Carolina voters surveyed wanted the IRA to stick around, compared to 37% who’d rather see it go — a significant spread for a state that, prior to the passage of the climate law, was home to little in the way of clean energy development.

North Carolina now has a lot to lose with the potential repeal of the Inflation Reduction Act, as Heatmap’s Emily Pontecorvo has pointed out. The IRA brought more than 17,000 jobs to the state, along with $20 billion in investment spread out over 34 clean energy projects. Electric vehicle and charging manufacturers in particular have flocked to the state, with Toyota investing $13.9 billion in its Liberty EV battery manufacturing facility, which opened this past April.

As a fragile ceasefire between Israel and Iran takes hold, oil prices are now lower than they were before the conflict began on June 13.