You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

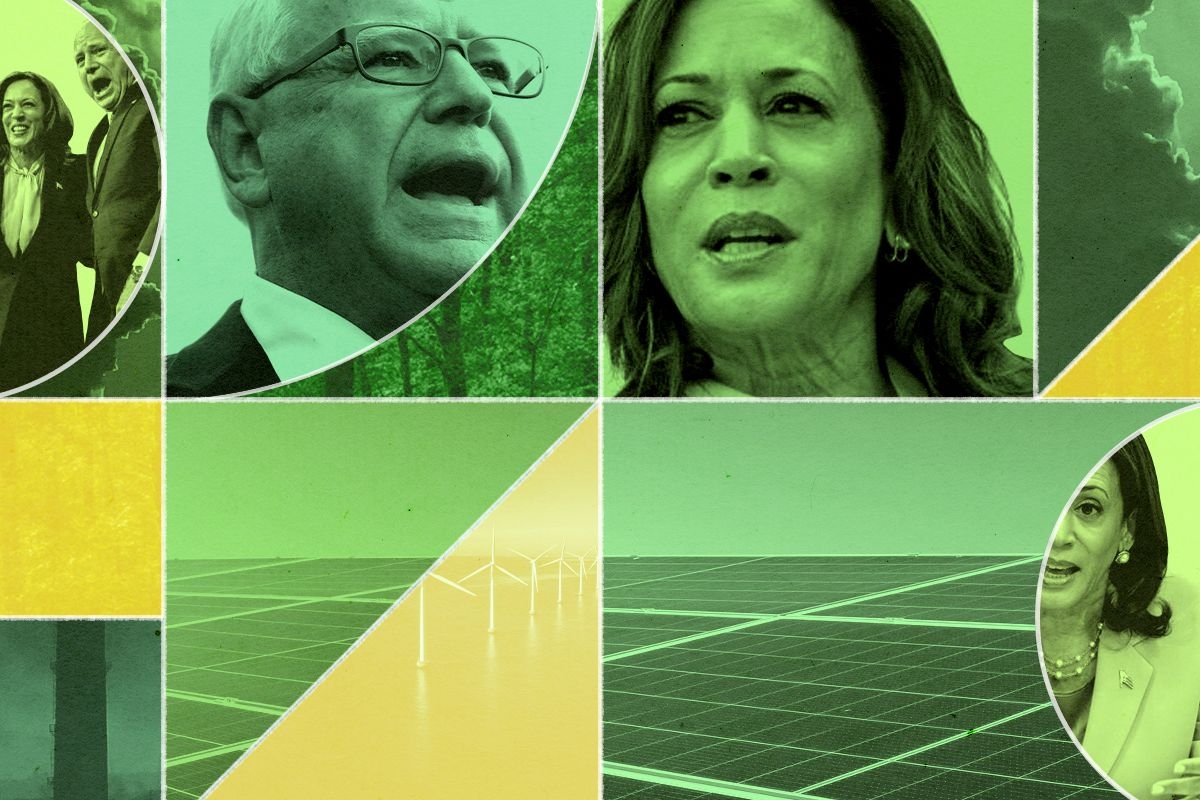

If Vice President Kamala Harris is elected president in November — as is looking increasingly likely — her term will last until the beginning of 2029. At that point, we’ll have a much better idea whether the planet is on track to hit the 1.5 degrees Celsius climate threshold that some expect it to cross that year; we’ll also know whether the United States is likely to meet the first goal of the Inflation Reduction Act: to reduce national greenhouse gas emissions to half of 2005 levels by 2030.

There is a lot riding on the outcome of the 2024 election, then. But even more to the point, there is a lot riding on how, and how aggressively, Harris extends President Biden’s climate policies. Last week, I spoke to nine different climate policy experts about what’s on their wishlists for a potential Harris-Walz administration and encountered resounding excitement about the opportunities ahead. I also encountered nine different opinions on how, exactly, Harris should capitalize on those opportunities, should she wind up in the White House come January.

That said, the ideas I heard largely coalesced into three main avenues of approach: The first would see Harris use her position to shore up the country’s existing climate policies, doubling down on spending and addressing loopholes in the IRA. A second path would involve aggressively expanding on Biden’s legacy, mainly through major new investments. The final and most ambitious path would involve Harris approaching climate change and the energy transition with an original and bold vision for the years ahead (though your priorities may vary).

The policy proposals that fall under these loosely organized paths aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive, and, as you’ll see, some of the advocate’s proposals fall into multiple categories. But it’s also true that by making everything a priority, nothing is. With that in mind, here are three approaches climate insiders say Harris could take if she wins the White House in November.

Before jumping headlong into expanding the country’s climate policies, the Harris administration could start by shoring up existing legislation — mainly, the loopholes and oversights in the Inflation Reduction Act. “The IRA was the biggest climate investment in history and fundamentally changed the emissions trajectory of the U.S — but the work is not done,” Adrian Deveny, founder of the decarbonization strategy group Climate Vision who previously worked on the IRA as Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer’s director of energy and environmental policy, told me.

As things stand, the policies in the IRA alone won’t be enough to meet President Biden’s goal of halving the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions by 2030; to do that, the U.S. would “need to pass another IRA-sized bill,” Deveny said. Until that happens, filling the IRA’s emissions gaps will take a lot of work “in every sector of the economy,” he added.

Lena Moffitt, the executive director of Evergreen Action — which has already released a comprehensive 2025 climate roadmap for a Harris administration — told me that the task of “doubling down on Biden’s climate legacy as a job creator” will run through rebuilding and expanding the grid and revitalizing industry and rural economies, two projects that started in the IRA but remain incomplete. “We’d love to see a day one executive order from the White House outlining a plan to create American jobs and seize the mantle of leadership by building clean energy and clean tech in the United States,” she told me.

Permitting reform is part of that — and could be another piece of yet-unfinished business Harris will need to wrap up. “If that doesn’t get done this year, that is what we have to look to as soon as possible during a future Harris administration,” Harry Godfrey, who leads Advanced Energy United's Federal Investment and Manufacturing Working Group, told me.

That’s not the only regulatory matter still up in the air. Austin Whitman, the CEO of The Climate Change Project, a non-profit that offers climate certification labeling and helps businesses reduce their emissions, told me that the Federal Trade Commission, for example, still hasn’t updated its green guides — “a loose collection of recommendations to companies on how to behave to not violate the FTC Act” — since 2012. “We just need a clear timeline and a sense of direction of where that whole process is going,” Whitman told me. Additionally, he said that the government has a substantial and outstanding role to play in standardizing and streamlining emissions reporting practices for businesses — which, while perhaps not “very sexy,” are necessary to “relieve the administrative burden so companies can focus on decarbonization.”

The last piece: Make sure everything that’s already in place is actually working. “We’re seeing that states and local governments need additional capacity to manage [the IRA] money well,” Jillian Blanchard, the director of Lawyers For Good Government’s climate change program, told me. Harris could help by enacting “more tangible policies like granting federal funding to hire community engagement specialists or liaisons or paying for the time of community leaders to provide local governments with key information on where the communities are that need to be benefited, and what they need.” She also floated the idea of a Community Change Grant extension to help get federal funding to localities more directly.

“One of the criticisms of the Inflation Reduction Act is that it didn’t do ‘X’ — whatever ‘X’ is,” Costa Samaras, the director of the Wilton E. Scott Institute for Energy Innovation at Carnegie Mellon and a former senior White House energy official, told me. “And in reality, it probably did. It just didn’t do it big enough.”

As opposed to those who thought Harris should take a quieter, dare I say conservative approach to advancing the U.S. climate agenda, Samaras told me he wanted to see Harris pump up the volume. The current climate moment requires “attacking the places where we need to immediately make big emissions cuts and big resilience investments. This is the industrial sector, the cultural sector, heavy transportation, as well as making sure that our cities and communities are built for people.”

There are plenty of existing programs that could take some supersizing. Godfrey of Advanced Energy United brought up the home energy rebate programs, arguing that as things stand, those resources are only serving “a fraction of the eligible population.” Blanchard of Lawyers For Good Government also pointed out that the Environmental Protection Agency had almost 300 Climate Pollution Reduction Grant applications totaling more than $30 billion in requests — but only $4.3 billion to hand out. “There are local governments, state governments, tribal nations, and territories hungry for this money to implement clean energy projects,” she said. “There are plans that are ready to go if there are additional federal award dollars in the future.”

Another place Harris could expand on Biden’s legacy would be by reinstating the U.S. as a climate leader on the world stage. “We need to say, ‘climate is back on the table,’” Whitman of The Climate Change Project told me. “It’s a main course, and we’re going to talk about it” — something that would give us “a more credible seat at the negotiating table at the COPs.”

Perhaps most importantly, though, Harris needs to use her term to start looking toward the future. As Deveny of Climate Vision told me, “We designed the IRA to think about meeting our 2030 target. And now we have to think about 2035.” Looking ahead isn’t “just about extending policies,” in other words, but about anticipating new technologies and opportunities that could arise in the next decade — and Harris, if elected, should step up to the challenge.

Some believe Harris shouldn’t limit herself to the framework of the IRA as it exists now — that she needs to dream bigger and better than anything seen under the Biden administration. “The question is: Are we going to just ride the coattails of the IRA as if this problem is mostly solved? Or are we going to put forward a whole new, bold vision of how we can take things on?” Saul Levin, the political director of the Green New Deal Network, wondered to me.

According to Deveny of Climate Vision, that means continuing to build on “our industrial renaissance.”

“We have really awakened a sleeping giant of clean industrial manufacturing in this country to make solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries,” he explained. “We can also lead the world in clean industrial manufacturing for steel, cement, and other heavy industry projects.” Samaras of Carnegie Mellon, too, shared this vision. “By the end of a potential Harris Administration first term, the path to zero emissions should be visible everywhere,” he told me. Also on his wishlist were “abundant energy-efficient and affordable housing, accessible clean mobility infrastructure everywhere, schools and post offices as community clean energy and resilience hubs, and climate-smart agriculture and nature-based solutions across the country,” plus greater investment in adaptation.

“The fact is that both the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act are the largest investments in resilience we’ve ever done,” he said. But “we have to think about it the same way we have to think about mitigation,” he went on. “It’s the largest thing we’ve ever done — comma, so far.”

One of the biggest openings for Harris to distinguish herself from Biden, though, would be by taking a tougher tone with big polluters. Biden had shown less of an appetite for going after businesses, several times kicking the can down the road on a decision to what would have been his second term. Harris, by contrast, is well positioned with her background as a prosecutor and already went as far as to call for a “climate pollution fee” and the creation of an independent Office of Climate and Environmental Justice and Accountability during her 2019-2020 campaign.

“We love seeing her already reference from the stump that there is a lot that she can do with Congress or through the executive branch to hold polluters accountable for the toll that they have taken on families and our climate,” Moffitt of Evergreen Action told me. “That could look like a host of things, from repealing subsidies to using the Department of Justice to hold polluters accountable.” Maria Langholz, the senior director of Arc Initiatives, a strategy group that works with climate-related organizations, told me in an email that her team would also like to see the Harris administration revoke the presidential permit for Enbridge’s Line 5 pipeline as high, in addition to developing a public interest determination “that fully addresses the social, environmental, and economic impacts of LNG.”

But Levin, more than anyone else, wanted to see Harris pursue a “moonshot campaign from day one,” he said. “Hoping that tweaking the IRA is an appropriate solution to climate change is totally out of step with mainstream scientific consensus. It’s absolutely ridiculous. At the end of the day, we need to fundamentally transform our economy so that all people can survive climate change.” To have a prayer of meeting the IRA’s climate goals — let alone putting a meaningful dent in America’s contribution to global emissions — the U.S. must “invest trillions of dollars in transforming our transportation system, our building sector, our food and agriculture sector, and every part of the economy so that we can create a livable, sustainable world forever that works for everyone.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

On nuclear tax credits, BLM controversy, and a fusion maverick’s fundraise

Current conditions: A third storm could dust New York City and the surrounding area with more snow • Floods and landslides have killed at least 25 people in Brazil’s southeastern state of Minas Gerais • A heat dome in Western Europe is pushing up temperatures in parts of Portugal, Spain, and France as high as 15 degrees Celsius above average.

The Department of Energy’s in-house lender, the Loan Programs Office — dubbed the Office of Energy Dominance Financing by the Trump administration — just gave out the largest loan in its history to Southern Company. The nearly $27 billion loan will “build or upgrade over 16 gigawatts of firm reliable power,” including 5 gigawatts of new gas generation, 6 gigawatts of uprates and license renewals for six different reactors, and more than 1,300 miles of transmission and grid enhancement projects. In total, the package will “deliver $7 billion in electricity cost savings” to millions of ratepayers in Georgia and Alabama by reducing the utility giant’s interest expenses by over $300 million per year. “These loans will not only lower energy costs but also create thousands of jobs and increase grid reliability for the people of Georgia and Alabama,” Secretary of Energy Chris Wright said in a statement.

Over in Utah, meanwhile, the state government is seeking the authority to speed up its own deployment of nuclear reactors as electricity demand surges in the desert state. In a letter to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission dated November 10 — but which E&E News published this week — Tim Davis, the executive director of Utah’s Department of Environmental Quality, requested that the federal agency consider granting the state the power to oversee uranium enrichment, microreactor licensing, fuel storage, and reprocessing on its own. All of those sectors fall under the NRC’s exclusive purview. At least one program at the NRC grants states limited regulatory primacy for some low-level radiological material. While there’s no precedent for a transfer of power as significant as what Utah is requesting, the current administration is upending norms at the NRC more than any other government since the agency’s founding in 1975.

Building a new nuclear plant on a previously undeveloped site is already a steep challenge in electricity markets such as New York, California, or the Midwest, which broke up monopoly utilities in the 1990s and created competitive auctions that make decade-long, multibillion-dollar reactors all but impossible to finance. A growing chorus argues, as Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote, that these markets “are no longer working.” Even in markets with vertically-integrated power companies, the federal tax credits meant to spur construction of new reactors would make financing a greenfield plant is just as impossible, despite federal tax credits meant to spur construction of new reactors. That’s the conclusion of a new analysis by a trio of government finance researchers at the Center for Public Enterprise. The investment tax credit, “large as it is, cannot easily provide them with upfront construction-period support,” the report found. “The ITC is essential to nuclear project economics, but monetizing it during construction poses distinct challenges for nuclear developers that do not arise for renewable energy projects. Absent a public agency’s ability to leverage access to the elective payment of tax credits, it is challenging to see a path forward for attracting sufficient risk capital for a new nuclear project under the current circumstances.”

Steve Pearce, Trump’s pick to lead the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management, wavered when asked about his record of pushing to sell off federal lands during his nomination hearing Wednesday. A former Republican lawmaker from New Mexico, Pearce has faced what the public lands news site Public Domain called “broad backlash from environmental, conservation, and hunting groups for his record of working to undermine public land protections and push land sales as a way to reduce the federal deficit.” Faced with questions from Democratic senators, Pearce said, “I’m not so sure that I’ve changed,” but insisted he didn’t “believe that we’re going to go out and wholesale land from the federal government.” That has, however, been the plan since the start of the administration. As Heatmap’s Jeva Lange wrote last year, Republicans looked poised to use their trifecta to sell off some of the approximately 640 million acres of land the federal government owns.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

At Tuesday’s State of the Union address, as I told you yesterday, Trump vowed to force major data center companies to build, bring, or buy their own power plants to keep the artificial intelligence boom from driving up electricity prices. On Wednesday, Fox News reported that Amazon, Google, Meta, Microsoft, xAI, Oracle, and OpenAI planned to come to the White House to sign onto the deal. The meeting is set to take place sometime next month. Data centers are facing mounting backlash. Developers abandoned at least 25 data centers last year amid mounting pushback from local opponents, Heatmap's Robinson Meyer recently reported.

Shine Technologies is a rare fusion company that’s actually making money today. That’s because the Wisconsin-based firm uses its plasma beam fusion technology to produce isotopes for testing and medical therapies. Next, the company plans to start recycling nuclear waste for fresh reactor fuel. To get there, Shine Technologies has raised $240 million to fund its efforts for the next few years, as I reported this morning in an exclusive for Heatmap. Nearly 63% of the funding came from biotech billionaire Patrick Soon-Shiong, who will join the board. The capital will carry the company through the launch of the world’s largest medical isotope producer and lay the foundations of a new business recycling nuclear waste in the early 2030s that essentially just reorders its existing assembly line.

Vineyard Wind is nearly complete. As of Wednesday, 60 of the project’s 62 turbines have been installed off the coast of Massachusetts. Of those, E&E News reported, 52 have been cleared to start producing power. The developer Iberdrola said the final two turbines may be installed in the next few days. “For me, as an engineer, the farm is already completed,” Iberdrola’s executive chair, Ignacio Sánchez Galán, told analysts on an earnings call. “I think these numbers mean the level of availability is similar for other offshore wind farms we have in operation. So for me, that is completed.”

That doesn’t mean it plans to produce electricity anytime soon.

Greg Piefer thinks nearly all his rivals in the race to commercialize fusion are doing it backward.

Of the 59 companies tracked in the Fusion Industry Association’s latest annual survey, 48 are primarily focused on generating electricity, off-grid energy, or industrial heat by harnessing the power produced when two atoms fuse together in the same type of reaction that fuels the sun. Just four are following the path of Shine Technologies and using plasma beam energy to manufacture rare and extremely valuable radioisotopes for breakthrough cancer treatments — 10 if you count the startups with a secondary medical business.

“We’re a bit different from fusion companies trying to sell the single product of electricity,” Piefer, the chief executive of Wisconsin-based Shine Technologies, told me. “The basic premise of our business is fusion is expensive today, so we’re starting by selling it to the highest-paying customers first.”

Shine Technologies’ contrarian strategy is winning over investors. On Thursday, the company plans to announce a $240 million Series E round, Heatmap can report exclusively. The funding, nearly 63% of which came from biotech billionaire Patrick Soon-Shiong, will provide enough capital to carry the company to the launch of the world’s largest medical isotope producer and lay the foundations of a new business recycling nuclear waste.

For now, Piefer said, Shine’s business is blasting uranium with enough extremely hot plasma beam energy to generate medical isotopes such as molybdenum-99 for diagnostic imaging or lutetium-177 for targeted cancer therapies. In the next few years, however, Shine Technologies is looking to apply its methods to recycling and reducing radioactive waste from commercial fission reactors’ spent fuel. Only then, sometime a decade from now, will the company start working on power plants.

“I would essentially define electricity as the lowest-paying customer of significance for fusion today,” Piefer said.

Soon-Shiong contributed $150 million to the funding pool via NantWorks, the biotech company he founded. Other investors include the financial services giant Fidelity Investments, the American division of the Japanese industrial conglomerate Sumitomo Corporation, the Texas investment bank Pelican Energy Partners, the healthcare-focused investor Deerfield Management, and the global asset manager Oaktree Capital. As part of the deal, Soon-Shiong — known outside the medical industry as the owner of the Los Angeles Times — will join Shine Technologies’ board of directors.

Since its founding in 2005, Shine has brought down the cost per fusion reaction by a thousandsfold. Over a Zoom call, Piefer pointed out the window behind him in his office in Janesville, Wisconsin, nearly two hours southwest of Milwaukee. In the afternoon sun was a gray, nondescript-looking warehouse. Inside, construction was underway on the world’s largest facility for producing medical isotopes. Dubbed Chrysalis, the flagship plant is set to come online in 2028.

“We’ll make 20 million doses of medicine per year with it,” he said. “It’ll be the biggest beneficial use of fusion for humans ever, and we expect it to be the dominant technology for decades. This will be the way the United States produces neutron-based radioisotopes probably for the next 50 years.”

To make medicine, the company follows four steps. First, it dissolves uranium. Next, it irradiates the material with the plasma beam. Then comes the separation process to remove valuable isotopes from the other radioactive material. Finally leftover uranium gets recycled back into the process. Rinse and repeat.

“It’s the first closed loop ever used for producing medicine this way,” Piefer said.

To recycle spent nuclear fuel, the company just remixes those steps, he said.

“You dissolve uranium from the nuclear waste. You separate out valuable materials. You recycle the uranium and plutonium in a reactor,” Piefer said. Then fusion comes in with the plasma beam technology to transform highly radioactive material that stays dangerous for longer than Homo sapiens is known to have existed into something that decays in half-lives that take years, decades, or centuries rather than millennia, decamillennia, and centimillennia.

“There’s about half a percent of long-lived nuclear waste from fission that we don’t know what to do with. It lives basically forever. We don’t have a use for it. But if you hit it with fusion neutrons, it becomes short-lived,” Piefer said. “So it’s the same four steps. For medicine, it goes one, two, three, four. For recycling it goes one, three, four, two.”

Not only is the market for testing and medical isotopes already worth billions of dollars, it’s on track to more than double in the next decade. Currently, it’s largely served by what Piefer called “60-year-old fission reactors.”

“These are specialized research reactors that are very cold and very constrained from a capacity standpoint,” he said. “You can buy new ones, but it takes billions of dollars and probably two decades to bring a new reactor online.”

By contrast, Shine Technologies broke ground on Chrysalis in 2019, and is set to complete the project at what Piefer said would be an eighth the cost of building a new research reactor.

The U.S. government, meanwhile, is helping to fund the next phase of Shine Technologies’ business. Just a few weeks ago, the Department of Energy gave the company a share of $19 million split between five companies looking to commercialize reprocessing technology. Last year, the company inked a deal with the reactor fuel startup Standard Nuclear to sell the fuel-grade material it recovers from recycling.

In both the fusion and next-generation fission industries, companies often lure investors by promising to pull off several very challenging things at once, said Chris Gadomski, the lead nuclear analyst at the consultancy BloombergNEF.

Oklo, a stock market darling for its planned microreactor and power plant business, was also among the recipients of the federal funding for waste reprocessing. Amazon-backed microreactor developer X-energy just won approval to start manufacturing the rare and expensive form of reactor fuel known as TRISO. TAE Technologies, the fusion startup that merged in December with the parent company of President Donald Trump’s social media network TruthSocial in a bid to build the world’s first fusion power plant, also has a subsidiary producing medical isotopes.

“I usually look at it as a distressing sign when you have an energy company tackling four or five different things,” Gadomski said. “But Shine is really a medical device company that is focused on isotopes but whose technology can also reprocess spent fuel — and, by the way, it can be applied down the road to energy.”

So far, Shine’s technology has followed a similar Moore’s Law trajectory to semiconductors.

From roughly 1990 to 2000, microchips used in workstations increased their computation rate per dollar. Then came the gaming era from 2000 to 2015, when videogames drove demand for more and more efficient semiconductors, with upgrades on average every other year. From 2015 until roughly the debut of ChatGPT in 2022, the high-speed computing applications spurred on chip upgrades at a similar rate. Now the artificial intelligence era is upon us, transforming chipmakers such as Nvidia into goliaths seemingly overnight.

Piefer sees Shine Technologies on its own 35-year timeline. From 2010 to roughly 2023, testing dominated the business. From then until about 2028, medical isotopes are the new play. The recycling pilot plant set to come online after 2030 will kick off the reprocessing period. And finally, sometime in the 2040s, Piefer wants to get into energy production.

“It’s a different approach than most,” he said.

“Don’t get me wrong, moonshots have their place, too,” he added. “But I feel very confident in this path.”

After a disappointing referendum in Maine, campaigners in New York are taking their arguments straight to lawmakers.

As electricity affordability has become the issue on every politician’s lips, a coalition of New York state lawmakers and organizations in the Hudson Valley have proposed a solution: Buy the utility and operate it publicly.

Assemblymember Sarahana Shrestha, whose district covers the mid-Hudson Valley, introduced a bill early last year to buy out the Hudson Valley’s investor-owned utility, Central Hudson Gas and Electric, and run it as a state entity. That bill hung around for a while before Shrestha reintroduced it to committee in January. It now has more than a dozen co-sponsors, a sign that the idea is gaining traction in Albany.

With politicians across the country in a frenzy to quell voters’ growing anxieties over their power bills, public power advocates are seizing the moment to make a renewed case that investor-owned utilities are to blame for rising prices. A victory for public power in the Hudson Valley would be the movement’s biggest win in decades — and could serve as a blueprint for other locales.

Shrestha’s proposal, while ambitious, draws on a long history of public power campaigns in the United States, stretching from the late 1800s to the New Deal 1930s to the present. Most recently, a 2023 referendum in Maine would have seen the state take over its two largest utilities; organizers argued the move would improve service and lower rates. But as Emily Pontecorvo covered for Heatmap, Maine voters rejected the referendum by a nearly 40-point margin. Public power advocates chalked up the loss to Maine’s investor-owned utilities outspending the proposition’s supporters by more than 30 to 1.

The current Hudson Valley campaign has a lot in common with Maine’s. In both, utilities rolled out faulty billing systems that overcharged customers, fueling resentment. Both targeted utilities owned by foreign corporations (Central Hudson is owned by Fortis, a Canadian company; Central Maine Power is owned by a subsidiary of Iberdrola, a Spanish company, while Versant, another utility in the state, is a subsidiary of Enmax, a Canadian corporation). And both took place amid rate hikes.

Shrestha has spent the past year working her district, holding town halls to sell the bill to her constituents. At each one she presents the same schpiel: “I gave people a little brief story of each of the different notable fights, from Long Island Power Authority to Massena to Maine to Rochester,” she told me, “because I also want people to understand that our fight is not happening in isolation.”

Public power advocates in the Hudson Valley are certainly applying lessons from the Maine defeat to their own campaign. For one, the venue is paramount. This time, public power campaigners are gearing up for a fight in the statehouse rather than the ballot box.

Unlike a ballot proposition, state legislation typically doesn’t attract millions of dollars in television and radio advertising from deep-pocketed utilities. Sandeep Vaheesan, a legal scholar and public power expert, told me that passing a law may be a more feasible route to victory for public power.

“Legislative fights are more winnable because referenda end up being messaging wars,” Vaheesan told Heatmap. “And more often than not, the side that has money can win that war.”

The message itself is also key. One lesson Maine organizers walked away with is that affordability is a winning strategy — an insight that has only gotten more robust over the past several months.

The Climate & Community Institute, a progressive climate think tank, released a report in November reflecting on the Maine referendum that put numbers to the campaigners’ intuition. “While climate change was an issue for many in our polling,” the report states, “it often took a backseat to problems Mainers continue to experience, like rising costs and power shutoff risks.” The group also pointed me to a survey it did in the fall of 2023 — years before data centers and energy demand became top-tier political issues — in which 69% of voters said they were worried about climate change, but 85% said they were worried about energy costs.

So how could public power lower costs for ratepayers?

“If you take shareholders out of the picture — if you replace private debt with cheaper public debt — you can lower rates pretty quickly and bring energy bills down,” Vaheesan argued.

The proposed Hudson Valley Power Authority wouldn’t have a profit motive; its return on equity, currently 9.5% for Central Hudson, would be reduced to zero. As a public entity, HVPA could also access capital at much lower interest rates than a private company and would be exempt from state and federal taxes.

Investor-owned utilities also inflate customers’ bills with unnecessary capital spending, Shrestha told me.

“The only way they can drive up their profits is by expanding their capital infrastructure, which is a very rare and unique characteristic of this industry,” she said, noting that a company like Walmart can’t make a profit by overspending. “So we’re stuck with a grid that is unnecessarily bloated and cumbersome and not at all efficient.”

A feasibility report commissioned by HVPA supporters and released in December estimates that ratepayers would see their bills go down by 2% in the first year after the public takeover — and result in 14% lower bills by 2055. A competing report, issued by opponents of the legislation, claimed the delivery portion of charges could increase by 36% under HVPA due to the cost of buying out Central Hudson, though advocates criticized the report for failing to publish any data.

Hudson Valley public power supporters can take another lesson from Maine to counter a combative utility. The two Maine utilities estimated the cost for the state to acquire them would be billions of dollars more than what public power advocates estimated — though in a televised debate, an anti-referendum representative refused to defend the stated numbers until the moderator instructed her to do so.

Lucy Hochschartner, the deputy campaign manager for Pine Tree Power (Maine’s proposed state-run utility), said she often assuaged voters’ concerns over the acquisition price by comparing it to buying a house.

“Right now we pay a really high rent to [Central Maine Power],” Hochschartner told us. “We pay them more than a billion dollars in revenue a year through our electric grid. And instead we could have moved to a low-cost mortgage.”

With a public acquisition, the cost of buying the electrical and gas systems would be funded through revenue bonds, paid off through customers’ bills over time. However a spokesperson for Central Hudson, Joe Jenkins, said the company would launch a legal battle rather than agree to sell its assets to New York State.

“Fortis has made no inclination that the company is for sale,” Jenkins told me. “So to take over a company by means of eminent domain, I believe that our parents would want to see this through a court.”

While a legal battle could be costly, public power advocates say the cost of inaction is also high. Winston Yau, an energy and industrial policy manager at the Climate & Community Institute, told me that publicly run utilities are better equipped to lead the transition to carbon-free power and adapt to a warming and more turbulent climate.

“Climate disasters and extreme weather events and heat waves are a major and increasing cause of rising utility bills,” Yau said. “In the coming decades, a significant amount of new investment will be needed.”