You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Why the Manchin-Barrasso bill might not be worth it.

Senator Joe Manchin’s new permitting deal is the best shot Congress will get this year to boost transmission and renewables. It may also lock in generations of future fossil fuel production and exports.

To many climate activists, that’s not a trade worth making.

Tomorrow, the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee will vote on a deal Manchin struck with the panel’s top Republican, John Barrasso, that couples faster transmission and renewable energy approvals and restrictions on litigation with much stronger requirements for regular oil, gas, and coal lease sales on federal lands. It would also restrict the Energy Department from continuing its pause on liquified natural gas export terminal approvals (an action that has already been overturned in court) and also, activists note, potentially bar the federal government from having authority over oil and gas drill sites on private lands. Critics say this would take away a tool regulators in Washington can use to require a well — a potential source of methane, the hyper-potent greenhouse gas — be plugged in the event the owner goes bankrupt and abandons the site.

The environmentalist reaction to the bill has been swift and loud, with a broad swath of organizations coming out fiercely against its passage. Even some groups seen as more business-friendly, such as the Environmental Defense Fund, praised the transmission bits while calling out “permitting proposals drafted without meaningful consultation of frontline communities” and proclaiming the fossil fuel language objectionable.

In a development that has quietly befuddled activists, a growing number of climate-friendly Democrats are coming out in favor of the legislation. Senators John Hickenlooper and Martin Heinrich, whose transmission proposals landed in the deal, are likely to vote in favor of the bill in committee this week.

“This legislation is our opportunity to unlock an American-made clean energy future,” Heinrich told Politico’s E&E News in a statement last week. “It will create good-paying jobs, grow our workforce, and help us deliver affordable and reliable electricity to all Americans — all while helping to meet our ambitious and urgent climate goals.”

Fossil fuels produced on federal lands for energy represent a substantial portion of the greenhouse gas emissions produced by the United States, a fact even Biden regulators have acknowledged while allowing more sales.

Whether this legislation can get to a full vote in the Senate is far from certain, and it’s a longshot for passage in this Congress. The bill goes further in favor of fossil fuels than the 2022 Manchin permitting deal, which was blocked by a confluence of opposition from environmentalists and far-right legislators that wanted an even more aggressive approach to overhauling environmental laws.

The same sort of coalition could stall this bill. But it would not surprise me if many more Democrats added their voices and votes in support. Over my years of reporting in Congress, I found a growing sense of frustration in Democratic circles at the lack of shovel-ready projects funded by the Inflation Reduction Act. They blame the National Environmental Policy Act, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, and pencil-pushing government officials. They’re tired of being asked “will they or won’t they” questions by Hill reporters about an ever-elusive permitting deal. So they may take any leap of faith to see those visual victories come to fruition faster — and help shore up political support for keeping the landmark climate law in place.

But that’s not how climate activists want them to see the bill. At all.

“Honestly, the amount of fossil fuels that can be deployed out of this far outweighs to me the gains we would get in transmission,” Johanna Bozuwa, executive director of the Climate and Community Project, told me. “I can understand the ‘for’ side of this. People are frustrated and they are sick of transmission not being deployed. Whereas the people who are against this bill are like, you need to think about the ramifications right now. Because what is being built into this bill is not next year’s emissions. It’s thirty years of emissions.”

Under Manchin-Barrasso, it would be much harder for the federal government to reduce how much land and sea it sells to fossil fuel companies every year.

The federal government regularly offers land for oil and gas companies to purchase for drilling sites. Deciding what land to sell and how much acreage to offer is normally a process decided at the bureaucratic level in tandem with industry input and environmental analyses. Under the Trump administration, lease sales were plentiful, though some had to be canceled because of inadequate climate and species reviews. Biden’s gone the opposite direction, but in order to win Manchin’s crucial vote, the IRA also complicated efforts to wind down fossil fuel auctions. One of Manchin’s non-negotiables for passing the bill was tying renewables leasing to millions of acres in mandatory oil and gas lease sales. In other words, to sell land for renewables, the government must now sell fossil fuels too.

Specifically, the IRA required the government to sell either millions of acres or the acreage that industry expresses interest in. So far, the Interior Department has found wiggle room by saying the acres they sell do not need to align precisely with properties requested by developers. Some in the oil and gas industry have accused the Biden administration of deliberately offering land the industry doesn’t want.

What Manchin-Barrasso would do, activists say, is essentially tie the hands of the government on this requirement. One provision would insert the phrase “for which expressions of interest have been submitted” into the mandatory onshore oil and gas leasing totals in the IRA, in effect putting industry’s desired land for leasing into statute as a requirement.

The bill would also require the government to hold annual offshore oil and gas lease sales at a time when the Biden administration is non-committal about auctioning in certain future years before environmental analyses are conducted.

There’s also the part about drilling on private land. A provision in Manchin-Barrasso appears to ban the federal government from requesting applications for permits to drill on private lands in circumstances when the government owns only the minerals beneath the surface but not above. These applications, known as APDs, are a key opportunity for federal regulators to require project developers post a bond on oil and gas wells as well as provide at least some level of info on environmental mitigation measures. Advocates emphasize this input also comes with an opportunity to intervene when an operator goes bankrupt and leaves a well unplugged, puking methane into the atmosphere. Manchin-Barrasso would instead cede that authority entirely to the states.

The bill would also require the government to process applications for coal leasing when the Biden administration is trying, essentially, to stop such leasing altogether.

Plus there’s the LNG export language which, well, explains itself.

For the energy transition, the bill would: create timetables for permitting renewables on federal rights-of-way; allow minimal environmental reviews of “low-disturbance” renewables construction projects; set a national goal of 50 gigawatts of renewables on federal land by 2030; ease geothermal permitting; provide easier environmental reviews to certain transmission activities within recently approved rights-of-way; grant FERC more authority to greenlight transmission projects that are considered to be in the “national interest;” and give hydropower projects more lenience on license extensions.

To some, that might be a worthwhile compromise — in the world of the possible, the deal may be the biggest opportunity for real gains on transmission and renewables this Congress. Should the November elections swing in the GOP’s direction, Democrats seeking a less fossil-friendly permitting deal would have essentially no chance because they could lose the House, the Senate and the White House, making this the only game in town, potentially for a long time. This bill would also achieve the elusive dream of a bipartisan compromise, where both sides get some but not all of what they want to achieve incremental progress on something viewed in D.C. as a long bemoaned problem.

“It is a really good bipartisan deal,” Xan Fishman of the Bipartisan Policy Center told me last week. “Not everyone is going to be happy.”

That argument isn’t convincing Rep. Jared Huffman, a top Democrat on the House Natural Resources Committee, who has emerged as a vocal critic of the Senate legislation. Huffman told me he wants to see transmission boosted “without massive giveaways to the fossil fuel industry.” When asked if he’s comfortable with accusations he’s holding up a bipartisan compromise, he simply said, “Whatever.”

“This is a bad deal. It just goes way too far in the direction of oil, gas and coal,” he told me. “We’ve got to stop dignifying this notion that to take one step forward on clean energy, we’ve got to take two steps backward on fossil fuel production.”

Brett Hartl, government affairs director for the Center for Biological Diversity, noted to me that when the Inflation Reduction Act was passed into law, Democrats had analyses showing the potential decarbonization benefits of the legislation — oil and gas warts and all. It ultimately showed net wins on climate, no matter how hard the other stuff may have been to swallow.

“Where’s the math that proves this is good?” he asked of the Manchin-Barrasso bill.

The truth is, we don’t know the climate impacts of this legislation yet, though experts are at work poring over the details. Meanwhile, some climate advocates are trying to get their own math out there. At the start of the week, I attended a small roundtable discussion with Jeremy Symons, a longtime environmental advocate who once worked on the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, as well as representatives of Public Citizen and Earthjustice and other reporters from Politico and S&P Global. At that roundtable, Symons presented an analysis declaring the legislation’s impact on LNG exports reviews alone would be equivalent to that from 165 coal-fired power plants and that it would take roughly 50 large renewable electricity-powered transmission lines to make up the negative climate impacts of the provision.

“Lawmakers should do some deep dive reevaluation and reach out to other outside experts to make sure that they fully understand [this bill],” Tyson Slocum of Public Citizen said at the roundtable.

Manchin’s office did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

And more on the week’s biggest conflicts around renewable energy projects.

1. Jackson County, Kansas – A judge has rejected a Hail Mary lawsuit to kill a single solar farm over it benefiting from the Inflation Reduction Act, siding with arguments from a somewhat unexpected source — the Trump administration’s Justice Department — which argued that projects qualifying for tax credits do not require federal environmental reviews.

2. Portage County, Wisconsin – The largest solar project in the Badger State is now one step closer to construction after settling with environmentalists concerned about impacts to the Greater Prairie Chicken, an imperiled bird species beloved in wildlife conservation circles.

3. Imperial County, California – The board of directors for the agriculture-saturated Imperial Irrigation District in southern California has approved a resolution opposing solar projects on farmland.

4. New England – Offshore wind opponents are starting to win big in state negotiations with developers, as officials once committed to the energy sources delay final decisions on maintaining contracts.

5. Barren County, Kentucky – Remember the National Park fighting the solar farm? We may see a resolution to that conflict later this month.

6. Washington County, Arkansas – It seems that RES’ efforts to build a wind farm here are leading the county to face calls for a blanket moratorium.

7. Westchester County, New York – Yet another resort town in New York may be saying “no” to battery storage over fire risks.

Solar and wind projects are getting swept up in the blowback to data center construction, presenting a risk to renewable energy companies who are hoping to ride the rise of AI in an otherwise difficult moment for the industry.

The American data center boom is going to demand an enormous amount of electricity and renewables developers believe much of it will come from solar and wind. But while these types of energy generation may be more easily constructed than, say, a fossil power plant, it doesn’t necessarily mean a connection to a data center will make a renewable project more popular. Not to mention data centers in rural areas face complaints that overlap with prominent arguments against solar and wind – like noise and impacts to water and farmland – which is leading to unfavorable outcomes for renewable energy developers more broadly when a community turns against a data center.

“This is something that we’re just starting to see,” said Matthew Eisenson, a senior fellow with the Renewable Energy Legal Defense Initiative at the Columbia University Sabin Center for Climate Change Law. “It’s one thing for environmentalists to support wind and solar projects if the idea is that those projects will eventually replace coal power plants. But it’s another thing if those projects are purely being built to meet incremental demand from data centers.”

We’ve started to see evidence of this backlash in certain resort towns fearful of a new tech industry presence and the conflicts over transmission lines in Maryland. But it is most prominent in Virginia, ground zero for American hyperscaler data centers. As we’ve previously discussed in The Fight, rural Virginia is increasingly one of the hardest places to get approval for a solar farm in the U.S., and while there are many reasons the industry is facing issues there, a significant one is the state’s data center boom.

I spent weeks digging into the example of Mecklenburg County, where the local Board of Supervisors in May indefinitely banned new solar projects and is rejecting those that were in the middle of permitting when the decision came down. It’s also the site of a growing data center footprint. Microsoft, which already had a base of operations in the county’s town of Boydton, is in the process of building a giant data center hub with three buildings and an enormous amount of energy demand. It’s this sudden buildup of tech industry infrastructure that is by all appearances driving a backlash to renewable energy in the county, a place that already had a pre-existing high opposition risk in the Heatmap Pro database.

It’s not just data centers causing the ban in Mecklenburg, but it’s worth paying attention to how the fight over Big Tech and solar has overlapped in the county, where Sierra Club’s Virginia Chapter has worked locally to fight data center growth with a grassroots citizens group, Friends of the Meherrin River, that was a key supporter of the solar moratorium, too.

In a conversation with me this week, Tim Cywinski, communications director for the state’s Sierra Club chapter, told me municipal leaders like those in Mecklenburg are starting to group together renewables and data centers because, simply put, rural communities enter into conversations with these outsider business segments with a heavy dose of skepticism. This distrust can then be compounded when errors are made, such as when one utility-scale solar farm – Geenex’s Grasshopper project – apparently polluted a nearby creek after soil erosion issues during construction, a problem project operator Dominion Energy later acknowledged and has continued to be a pain point for renewables developers in the county.

“I don’t think the planning that has been presented to rural America has been adequate enough,” the Richmond-based advocate said. “Has solar kind of messed up in a lot of areas in rural America? Yeah, and that’s given those communities an excuse to roll them in with a lot of other bad stuff.”

Cywinski – who describes himself as “not your typical environmentalist” – says the data center space has done a worse job at community engagement than renewables developers in Virginia, and that the opposition against data center projects in places like Chesapeake and Fauquier is more intense, widespread, and popular than the opposition to renewables he’s seeing play out across the Commonwealth.

But, he added, he doesn’t believe the fight against data centers is “mutually exclusive” from conflicts over solar. “I’m not going to tout the gospel of solar while I’m trying to fight a data center for these people because it’s about listening to them, hearing their concerns, and then not telling them what to say but trying to help them elevate their perspective and their concerns,” Cywinski said.

As someone who spends a lot of time speaking with communities resisting solar and trying to best understand their concerns, I agree with Cywinksi: the conflict over data centers speaks to the heart of the rural vs. renewables divide, and it offers a warning shot to anyone thinking AI will help make solar and wind more popular.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act is one signature away from becoming law and drastically changing the economics of renewables development in the U.S. That doesn’t mean decarbonization is over, experts told Heatmap, but it certainly doesn’t help.

What do we do now?

That’s the question people across the climate change and clean energy communities are asking themselves now that Congress has passed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which would slash most of the tax credits and subsidies for clean energy established under the Inflation Reduction Act.

Preliminary data from Princeton University’s REPEAT Project (led by Heatmap contributor Jesse Jenkins) forecasts that said bill will have a dramatic effect on the deployment of clean energy in the U.S., including reducing new solar and wind capacity additions by almost over 40 gigawatts over the next five years, and by about 300 gigawatts over the next 10. That would be enough to power 150 of Meta’s largest planned data centers by 2035.

But clean energy development will hardly grind to a halt. While much of the bill’s implementation is in question, the bill as written allows for several more years of tax credit eligibility for wind and solar projects and another year to qualify for them by starting construction. Nuclear, geothermal, and batteries can claim tax credits into the 2030s.

Shares in NextEra, which has one of the largest clean energy development businesses, have risen slightly this year and are down just 6% since the 2024 election. Shares in First Solar, the American solar manufacturer, are up substantially Thursday from a day prior and are about flat for the year, which may be a sign of investors’ belief that buyer demand for solar panels will persist — or optimism that the OBBBA’s punishing foreign entity of concern requirements will drive developers into the company’s arms.

Partisan reversals are hardly new to climate policy. The first Trump administration gleefully pulled the rug from under the Obama administration’s power plant emissions rules, and the second has been thorough so far in its assault on Biden’s attempt to replace them, along with tailpipe emissions standards and mileage standards for vehicles, and of course, the IRA.

Even so, there are ways the U.S. can reduce the volatility for businesses that are caught in the undertow. “Over the past 10 to 20 years, climate advocates have focused very heavily on D.C. as the driver of climate action and, to a lesser extent, California as a back-stop,” Hannah Safford, who was director for transportation and resilience in the Biden White House and is now associate director of climate and environment at the Federation of American Scientists, told Heatmap. “Pursuing a top down approach — some of that has worked, a lot of it hasn’t.”

In today’s environment, especially, where recognition of the need for action on climate change is so politically one-sided, it “makes sense for subnational, non-regulatory forces and market forces to drive progress,” Safford said. As an example, she pointed to the fall in emissions from the power sector since the late 2000s, despite no power plant emissions rule ever actually being in force.

“That tells you something about the capacity to deliver progress on outcomes you want,” she said.

Still, industry groups worry that after the wild swing between the 2022 IRA and the 2025 OBBBA, the U.S. has done permanent damage to its reputation as a business-friendly environment. Since continued swings at the federal level may be inevitable, building back that trust and creating certainty is “about finding ballasts,” Harry Godfrey, the managing director for Advanced Energy United’s federal priorities team, told Heatmap.

The first ballast groups like AEU will be looking to shore up is state policy. “States have to step up and take a leadership role,” he said, particularly in the areas that were gutted by Trump’s tax bill — residential energy efficiency and electrification, transportation and electric vehicles, and transmission.

State support could come in the form of tax credits, but that’s not the only tool that would create more certainty for businesses — considering the budget cuts states will face as a result of Trump’s tax bill, it also might not be an option. But a lot can be accomplished through legislative action, executive action, regulatory reform, and utility ratemaking, Godfrey said. He cited new virtual power plant pilot programs in Virginia and Colorado, which will require further regulatory work to “to get that market right.”

A lot of work can be done within states, as well, to make their deployment of clean energy more efficient and faster. Tyler Norris, a fellow at Duke University's Nicholas School of the Environment, pointed to Texas’ “connect and manage” model for connecting renewables to the grid, which allows projects to come online much more quickly than in the rest of the country. That’s because the state’s electricity market, ERCOT, does a much more limited study of what grid upgrades are needed to connect a project to the grid, and is generally more tolerant of curtailing generation (i.e. not letting power get to the grid at certain times) than other markets.

“As Texas continues to outpace other markets in generator and load interconnections, even in the absence of renewable tax credits, it seems increasingly plausible that developers and policymakers may conclude that deeper reform is needed to the non-ERCOT electricity markets,” Norris told Heatmap in an email.

At the federal level, there’s still a chance for, yes, bipartisan permitting reform, which could accelerate the buildout of all kinds of energy projects by shortening their development timelines and helping bring down costs, Xan Fishman, senior managing director of the energy program at the Bipartisan Policy Center, told Heatmap. “Whether you care about energy and costs and affordability and reliability or you care about emissions, the next priority should be permitting reform,” he said.

And Godfrey hasn’t given up on tax credits as a viable tool at the federal level, either. “If you told me in mid-November what this bill would look like today, while I’d still be like, Ugh, that hurts, and that hurts, and that hurts, I would say I would have expected more rollbacks. I would have expected deeper cuts,” he told Heatmap. Ultimately, many of the Inflation Reduction Act’s tax credits will stick around in some form, although we’ve yet to see how hard the new foreign sourcing requirements will hit prospective projects.

While many observers ruefully predicted that the letter-writing moderate Republicans in the House and Senate would fold and support whatever their respective majorities came up with — which they did, with the sole exception of Pennsylvania Republican Brian Fitzpatrick — the bill also evolved over time with input from those in the GOP who are not openly hostile to the clean energy industry.

“You are already seeing people take real risk on the Republican side pushing for clean energy,” Safford said, pointing to Alaska Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski, who opposed the new excise tax on wind and solar added to the Senate bill, which earned her vote after it was removed.

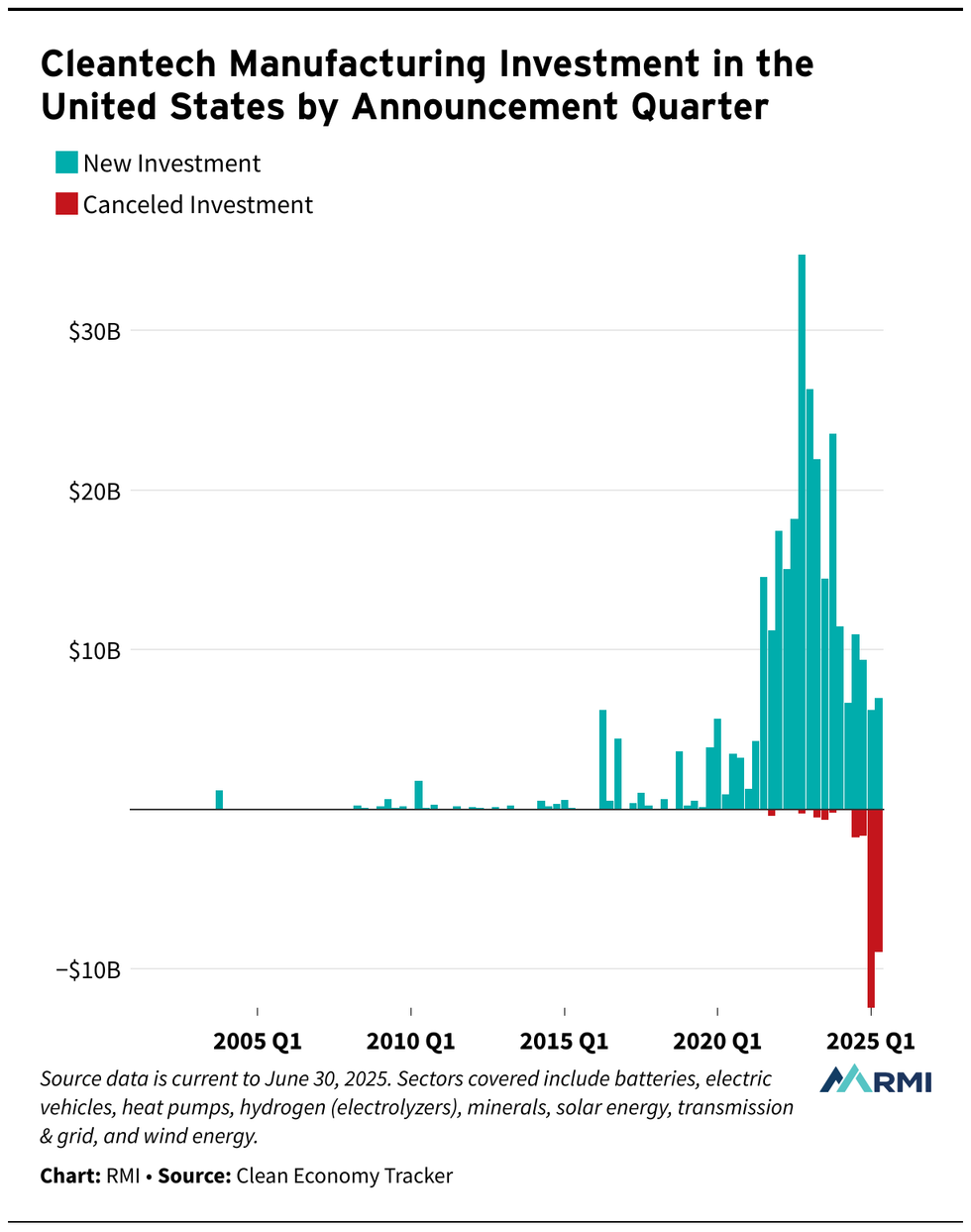

Some damage has already been done, however. Canceled clean energy investments adds up to $23 billion so far this year, compared to just $3 billion in all of 2024, according to the decarbonization think tank RMI. And that’s before OBBBA hits Trump’s desk.

The start-and-stop nature of the Inflation Reduction Act may lead some companies, states, local government and nonprofits to become leery of engaging with a big federal government climate policy again.

“People are going to be nervous about it for sure,” Safford said. “The climate policy of the future has to be polycentric. Even if you have the political opportunity to make a big swing again, people will be pretty gun shy. You will need to pursue a polycentric approach.”

But to Godfrey, all the back and forth over the tax credits, plus the fact that Republicans stood up to defend them in the 11th hour, indicates that there is a broader bipartisan consensus emerging around using them as a tool for certain energy and domestic manufacturing goals. A future administration should think about refinements that will create more enduring policy but not set out in a totally new direction, he said.

Albert Gore, the executive director of the Zero Emissions Transportation Association, was similarly optimistic that tax credits or similar incentives could work again in the future — especially as more people gain experience with electric vehicles, batteries, and other advanced clean energy technologies in their daily lives. “The question is, how do you generate sufficient political will to implement that and defend it?” he told Heatmap. “And that depends on how big of an economic impact does it have, and what does it mean to the American people?”

Ultimately, Fishman said, the subsidy on-off switch is the risk that comes with doing major policy on a strictly partisan basis.

“There was a lot of value in these 10-year timelines [for tax credits in the IRA] in terms of business certainty, instead of one- or two- year extensions,” Fishman told Heatmap. “The downside that came with that is that it became affiliated with one party. It was seen as a partisan effort, and it took something that was bipartisan and put a partisan sheen on it.”

The fight for tax credits may also not be over yet. Before passage of the IRA, tax credits for wind and solar were often extended in a herky-jerky bipartisan fashion, where Democrats who supported clean energy in general and Republicans who supported it in their districts could team up to extend them.

“You can see a world where we have more action on clean energy tax credits to enhance, extend and expand them in a future congress,” Fishman told Heatmap. “The starting point for Republican leadership, it seemed, was completely eliminating the tax credits in this bill. That’s not what they ended up doing.”