You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

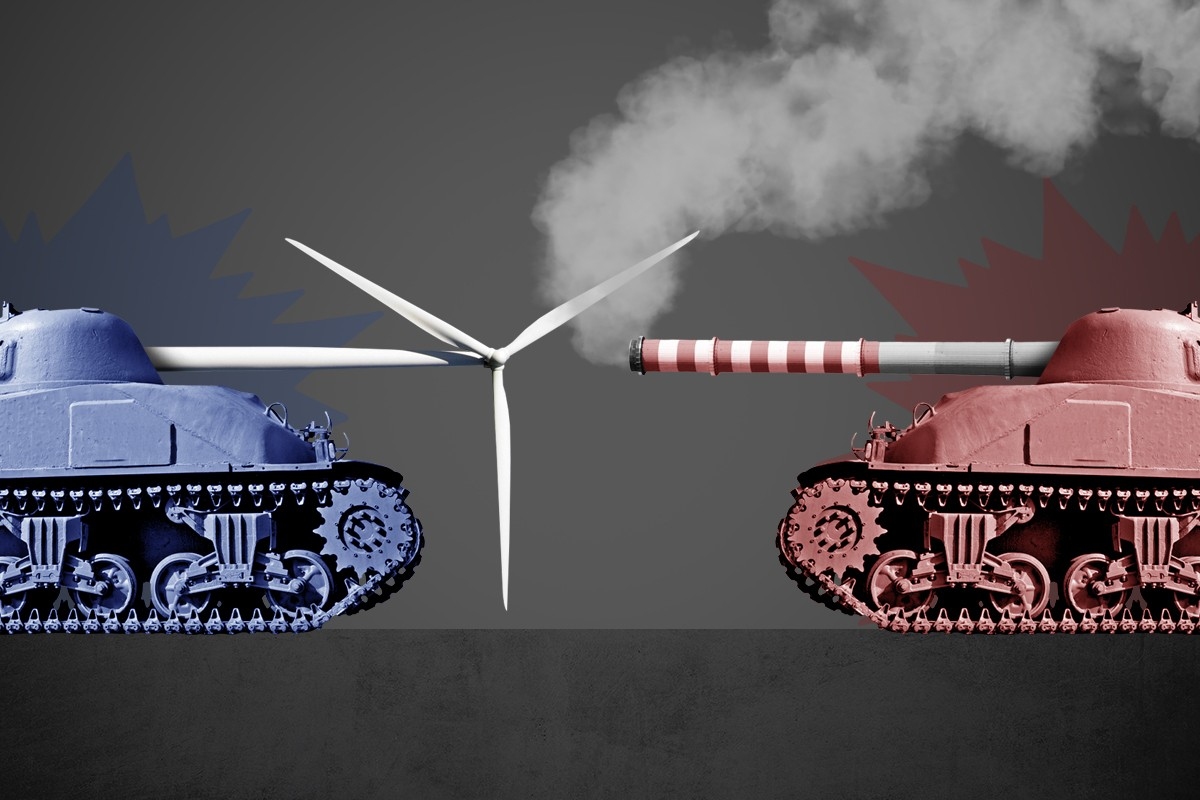

As blue states double down on renewables, a backlash is growing in red states.

The Inflation Reduction Act was the star of the show in statehouses across the United States this year. As state leaders wrapped up their legislative sessions, many not only tightened their own climate plans, but delivered an encore to the IRA by passing policies to maximize their share of the new federal clean energy funding.

But the applause hasn’t been universal. In a few key Republican-led legislatures, Biden’s climate maneuvers have produced a backlash. Lawmakers pushed through bills that could make cutting emissions a lot harder, making the map of U.S. climate policy start to look as polarized as that of abortion rights or gun control laws.

“There has been a tendency to think about the energy transition as almost automatic when the cost of clean energy technologies come down,” Matto Mildenberger, a political scientist at the University of California-Santa Barbara, told me. “But politics is a really important dimension that's often missed.”

Let’s look at a few examples. Back in February, Minnesota passed a law requiring the state’s utilities to use 100% carbon-free electricity by 2040. Democrats had just taken over the legislature, and they were just warming up. In April they created a $156 million “competitiveness fund” to help agencies and cities compete for the IRA’s clean energy programs. And last week, Democratic Governor Tim Waltz signed two additional laws, one earmarking funding for heat pumps and electric vehicles, and the other creating a new sales tax to support public transit.

Democrats took a similar approach in Colorado, passing new tax credits for many of the same technologies that the IRA funds to try and attract as much federal money into its economy as possible. Coloradans are now eligible for a $7,500 EV tax credit that can be stacked on the federal credit for a juicy $15,000 incentive.

Meanwhile, New York passed the first state-level ban on natural gas in new buildings in the country. Policymakers there also directed a state-run utility to start building renewable energy projects, taking advantage of a little-known provision in the IRA that enables public entities and nonprofits to cash in on federal tax credits.

But in other states, electeds are enacting what you could call anti-climate policies. Montana’s Republican Governor Greg Gianforte recently signed a law that bars state agencies from even considering greenhouse gas emissions when conducting environmental reviews for major projects. The legislature there also passed measures preempting local governments from requiring new buildings to be solar panel or EV-ready, and from placing any restrictions on the use of natural gas. At least 20 other states have enacted similar natural gas ban preemptions in recent years. A new anti-climate copycat bill also spread to a few states this year — Ohio and Tennessee each passed laws classifying natural gas as a source of clean energy.

In Texas, the Republican-controlled legislature is contemplating bills to publicly fund a fleet of new natural gas plants, while placing new, onerous regulations on wind and solar projects. Texas currently produces more wind and solar power than any other state, thanks to lax permitting requirements and an abundance of wind, sun, and undeveloped land. Now, lawmakers want developers of new wind and solar farms — as well as owners of existing projects — to do additional environmental reviews, get new approvals, and pay higher fees. Wind farms would have to be built at least 3,000 feet from neighboring property lines. The rules would not apply to fossil fuel plants.

Though the bill never made it out of committee, a group of Republican lawmakers in Wyoming even sought to “phase out” electric vehicle sales to protect the state’s oil and gas industry. The bill’s lead sponsor later said he supports electric vehicles, and was just trying to send a message to California, which made plans to eventually ban gas-powered vehicles last August.

And while Georgia is often held up as a leader in building a new clean economy, having attracted more clean energy investments since the IRA passed than any other state, Republican lawmakers there recently enacted a tax on public electric vehicle charging.

None of this is particularly surprising or new. To some extent, climate and clean energy policy has long followed party lines. As political scientist Leah Stokes documents in her book Short Circuiting Policy, states like Texas and Ohio have a history of enacting anti-climate policies that slowed the growth of renewables. Those were in large part driven by special interest groups backed by utilities and the fossil fuel industry.

Mildenberger said these efforts are ramping up now because the IRA has made the threat to these industries much more significant. “Increasingly, as some of these technologies are no longer cost competitive in a pure market competition framework, they need to use policy as a rearguard action to try and maintain their market share.”

There is evidence that at least some of these policies, like defining natural gas as clean energy and preempting any bans on the fuel, trace back to special interest groups like the American Legislative Exchange Council and the American Gas Association. What’s new is a push to turn these issues into culture wars by painting natural gas use as a matter of freedom or identity. Republican lawmakers have described a rash of anti-ESG bills, which also have roots with industry groups, as a crackdown on “woke” investing.

But Hanna Breetz, a political scientist at Arizona State University told me it would be a mistake to attribute the trend purely to industry influence or the usual reactionary politics. That view overlooks two other very real factors that she sees contributing to an increasingly polarized environment. One is that people in rural states are legitimately concerned about what a decarbonized future means for them in terms of land use and extraction. They are going to bear the brunt of landscape impacts from vast new solar and wind farms and lithium mines.

The second is genuine risks to reliability from a grid powered by increasing amounts of renewables and batteries that’s also serving an increasing number of electric appliances. “There are some very serious concerns that have yet to be dealt with, particularly in the face of climate change and weather-related issues,” said Breetz. She pointed to a recent report warning of blackouts in some parts of the country this summer, which highlighted diminished capacity from natural gas and coal plants as one potential cause. “I think there's a lot less ideological opposition within utilities than many people assume, and that they are scared to death about a lot of these reliability concerns.”

It’s hard to untangle the role of each of these components — industry influence, party politics, land use concerns, and technical challenges — when they all feed into one another. The effect could intensify as more and more people experience a bad blackout or are faced with a solar farm being built in a place they hold dear.

But also, it might not. If all goes according to Biden’s plan, the IRA will be a countervailing force that brings new jobs and economic growth to areas where political support for clean energy is in short supply. The majority of clean energy project announcements since the IRA was passed are in states like Georgia, Arizona, and South Carolina. Think of the new battery belt emerging in the South, or how many renewable energy projects are popping in Republican-held congressional districts.

“In three or five years that might make some of the extreme rhetoric and policy positions that we're seeing right now on the Republican side of the aisle a little bit more challenging to hold,” said Mildenberger. “My view is that even in some of the more fossil fuel intensive parts of the United States, the question of the energy transition is not if, but when. And to help manage the global climate crisis, that ‘when’ needs to be really soon.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

On electrolyzers’ decline, Anthropic’s pledge, and Syria’s oil and gas

Current conditions: Warmer air from down south is pushing the cold front in Northeast back up to Canada • Tropical Cyclone Gezani has killed at least 31 in Madagascar • The U.S. Virgin Islands are poised for two days of intense thunderstorms that threaten its grid after a major outage just days ago.

Back in November, Democrats swept to victory in Georgia’s Public Service Commission races, ousting two Republican regulators in what one expert called a sign of a “seismic shift” in the body. Now Alabama is considering legislation that would end all future elections for that state’s utility regulator. A GOP-backed bill introduced in the Alabama House Transportation, Utilities, and Infrastructure Committee would end popular voting for the commissioners and instead authorize the governor, the Alabama House speaker, and the Alabama Senate president pro tempore to appoint members of the panel. The bill, according to AL.com, states that the current regulatory approach “was established over 100 years ago and is not the best model for ensuring that Alabamians are best-served and well-positioned for future challenges,” noting that “there are dozens of regulatory bodies and agencies in Alabama and none of them are elected.”

The Tennessee Valley Authority, meanwhile, announced plans to keep two coal-fired plants operating beyond their planned retirement dates. In a move that seems laser-targeted at the White House, the federally-owned utility’s board of directors — or at least those that are left after President Donald Trump fired most of them last year — voted Wednesday — voted Wednesday to keep the Kingston and Cumberland coal stations open for longer. “TVA is building America’s energy future while keeping the lights on today,” TVA CEO Don Moul said in a statement. “Taking steps to continue operations at Cumberland and Kingston and completing new generation under construction are essential to meet surging demand and power our region’s growing economy.”

Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum said the Trump administration plans to appeal a series of court rulings that blocked federal efforts to halt construction on offshore wind farms. “Absolutely we are,” the agency chief said Wednesday on Bloomberg TV. “There will be further discussion on this.” The statement comes a week after Burgum suggested on Fox Business News that the Supreme Court would break offshore wind developers’ perfect winning streak and overturn federal judges’ decisions invalidating the Trump administration’s orders to stop work on turbines off the East Coast on hotly-contested national security, environmental, and public health grounds. It’s worth reviewing my colleague Jael Holzman’s explanation of how the administration lost its highest profile case against the Danish wind giant Orsted.

Thyssenkrupp Nucera’s sales of electrolyzers for green hydrogen projects halved in the first quarter of 2026 compared to the same period last year. It’s part of what Hydrogen Insight referred to as a “continued slowdown.” Several major projects to generate the zero-carbon fuel with renewable electricity went under last year in Europe, Australia, and the United States. The Trump administration emphasized the U.S. turn away from green hydrogen by canceling the two regional hubs on the West Coast that were supposed to establish nascent supply chains for producing and using green hydrogen — more on that from Heatmap’s Emily Pontecorvo. Another potential drag on the German manufacturer’s sales: China’s rise as the world’s preeminent manufacturer of electrolyzers.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

The artificial intelligence giant Anthropic said Wednesday it would work with utilities to figure out how much its data centers were driving up electricity prices and pay a rate high enough to avoid passing the costs onto ratepayers. The announcement came as part of a multi-pronged energy strategy to ease public concerns over its data centers at a moment when the server farms’ effect on power prices and local water supplies is driving a political backlash. As part of the plan, Anthropic would cover 100% of the costs of upgrading the grid to bring data centers online, and said it would “work to bring net-new power generation online to match our data centers’ electricity needs.” Where that isn’t possible, the company said it would “work with utilities and external experts to estimate and cover demand-driven price effects from our data centers.” The maker of ChatGPT rival Claude also said it would establish demand response programs to power down its data centers when demand on the grid is high, and deploy other “grid optimization” tools.

“Of course, company-level action isn’t enough. Keeping electricity affordable also requires systemic change,” the company said in a blog post. “We support federal policies — including permitting reform and efforts to speed up transmission development and grid interconnection — that make it faster and cheaper to bring new energy online for everyone.”

Syria’s oil reserves are opening to business, and Western oil giants are in line for exploration contracts. In an interview with the Financial Times, the head of the state-owned Syrian Petroleum Company listed France’s TotalEnergies, Italy’s Eni, and the American Chevron and ConocoPhillips as oil majors poised to receive exploration licenses. “Maybe more than a quarter, or less than a third, has been explored,” said Youssef Qablawi, chief executive of the Syrian Petroleum Company. “There is a lot of land in the country that has not been touched yet. There are trillions of cubic meters of gas.” Chevron and Qatar’s Power International Holding inked a deal just last week to explore an offshore block in the Mediterranean. Work is expected to begin “within two months.”

At the same time, Indonesia is showing the world just how important it’s become for a key metal. Nickel prices surged to $17,900 per ton this week after Indonesia ordered steep cuts to protection at the world’s biggest mine, highlighting the fast-growing Southeast Asian nation’s grip over the global supply of a metal needed for making batteries, chemicals, and stainless steel. The spike followed Jakarta’s order to cut production in the world’s biggest nickel mine, Weda Bay, to 12 million metric tons this year from 42 million metric tons in 2025. The government slashed the nationwide quota by 100 million metric tons to between 260 million and 270 million metric tons this year from 376 million metric tons in 2025. The effect on the global price average showed how dominant Indonesia has become in the nickel trade over the past decade. According to another Financial Times story, the country now accounts for two-thirds of global output.

The small-scale solar industry is singing a Peter Tosh tune: Legalize it. Twenty-four states — funny enough, the same number that now allow the legal purchase of marijuana — are currently considering legislation that would allow people to hook up small solar systems on balconies, porches, and backyards. Stringent permitting rules already drive up the cost of rooftop solar in the U.S. But systems small enough for an apartment to generate some power from a balcony have largely been barred in key markets. Utah became the first state to vote unanimously last year to pass a law allowing residents to plug small solar systems straight into wall sockets, providing enough electricity to power a laptop or small refrigerator, according to The New York Times.

The maker of the Prius is finally embracing batteries — just as the rest of the industry retreats.

Selling an electric version of a widely known car model is no guarantee of success. Just look at the Ford F-150 Lightning, a great electric truck that, thanks to its high sticker price, soon will be no more. But the Toyota Highlander EV, announced Tuesday as a new vehicle for the 2027 model year, certainly has a chance to succeed given America’s love for cavernous SUVs.

Highlander is Toyota’s flagship titan, a three-row SUV with loads of room for seven people. It doesn’t sell in quite the staggering numbers of the two-row RAV4, which became the third-best-selling vehicle of any kind in America last year. Still, the Highlander is so popular as a big family ride that Toyota recently introduced an even bigger version, the Grand Highlander. Now, at last, comes the battery-powered version. (It’s just called Highlander and not “Highlander EV,” by the way. The Highlander nameplate will be electric-only, while gas and hybrid SUVs will fly the Grand Highlander flag.)

The American-made electric Highlander comes with a max range of 287 miles in its less expensive form and 320 in its more expensive form. The SUV comes with the NACS port to charge at Tesla Superchargers and vehicle-to-load capability that lets the driver use their battery power for applications like backing up the home’s power supply. Six seats come standard, but the upgraded Highlander comes with the option to go to seven. The interior is appropriately high-tech.

Toyota will begin to build this EV later this year at a factory in Kentucky and start sales late in the year. We don’t know the price yet, but industry experts expect Highlander to start around $55,000 — in the same ballpark as big three-row SUVs like the Kia EV9 and Hyundai Ioniq 9 — and go up from there.

The most important point of the electric Highlander’s arrival, however, is that it signals a sea change for the world’s largest automaker. Toyota was decidedly not all in on the first wave (or two) of modern electric cars. The Japanese giant was content to make money hand over first while the rest of the industry struggled, losing billions trying to catch up to Tesla and deal with an unpredictable market for electrics.

A change was long overdue. This year, Toyota was slated to introduce better EVs to replace the lackluster bZ4x, which had been its sole battery-only model. That included an electrified version of the C-HR small crossover. Now comes the electrified Highlander, marking a much bigger step into the EV market at a time when other automakers are reining in their battery-powered ambitions. (Fellow Japanese brand Subaru, which sold a version of bZ4x rebadged as the Solterra, seems likely to do the same with the electric Highlander and sell a Subaru-labeled version of essentially the same vehicle.)

The Highlander EV matters to a lot of people simply because it’s a Toyota, and they buy Toyotas. This pattern was clear with the success of the Honda Prelude. Under the skin that car was built on General Motors’ electric vehicle platform, but plenty of people bought it because they were simply waiting for their brand, Honda, to put out an EV. Toyota sells more cars than anyone in the world. Its act of putting out a big family EV might signal to some of its customers that, yeah, it’s time to go electric.

Highlander’s hefty size matters, too. The five-seater, two-row crossover took over as America’s default family car in the past few decades. There are good EVs in this space, most notably the Tesla Model Y that has led the world in sales for a long time. By contrast, the lineup of true three-row SUVs that can seat six, seven, or even eight adults has been comparatively lacking. Tesla will cram two seats in the back of the Model Y to make room for seven people, but this is not a true third row. The excellent Rivian R1S is big, but expensive. Otherwise, the Ioniq 9 and EV9 are left to populate the category.

And if nothing else, the electrified Highlander is a symbolic victory. After releasing an era-defining auto with the Prius hybrid, Toyota arguably had been the biggest heel-dragger about EVs among the major automakers. It waited while others acted; its leadership issued skeptical statements about battery power. Highlander’s arrival is a statement that those days are done. Weirdly, the game plan feels like an announcement from the go-go electrification days of the Biden administration — a huge automaker going out of its way to build an important EV in America.

If it succeeds, this could be the start of something big. Why not fully electrify the RAV4, whose gas-powered version sells in the hundreds of thousands in America every year?

Third Way’s latest memo argues that climate politics must accept a harsh reality: natural gas isn’t going away anytime soon.

It wasn’t that long ago that Democratic politicians would brag about growing oil and natural gas production. In 2014, President Obama boasted to Northwestern University students that “our 100-year supply of natural gas is a big factor in drawing jobs back to our shores;” two years earlier, Montana Governor Brian Schweitzer devoted a portion of his speech at the Democratic National Convention to explaining that “manufacturing jobs are coming back — not just because we’re producing a record amount of natural gas that’s lowering electricity prices, but because we have the best-trained, hardest-working labor force in the history of the world.”

Third Way, the long tenured center-left group, would like to go back to those days.

Affordability, energy prices, and fossil fuel production are all linked and can be balanced with greenhouse gas-abatement, its policy analysts and public opinion experts have argued in a series of memos since the 2024 presidential election. Its latest report, shared exclusively with Heatmap, goes further, encouraging Democrats to get behind exports of liquified natural gas.

For many progressive Democrats and climate activists, LNG is the ultimate bogeyman. It sits at the Venn diagram overlap of high greenhouse gas emissions, the risk of wasteful investment and “stranded” assets, and inflationary effects from siphoning off American gas that could be used by domestic households and businesses.

These activists won a decisive victory in the Biden years when the president put a pause on approvals for new LNG export terminal approvals — a move that was quickly reversed by the Trump White House, which now regularly talks about increases in U.S. LNG export capacity.

“I think people are starting to finally come to terms with the reality that oil and gas — and especially natural gas— really aren’t going anywhere,” John Hebert, a senior policy advisor at Third Way, told me. To pick just one data point: The International Energy Agency’s latest World Energy Outlook included a “current policies scenario,” which is more conservative about policy and technological change, for the first time since 2019. That saw the LNG market almost doubling by 2050.

“The world is going to keep needing natural gas at least until 2050, and likely well beyond that,” Hebert said. “The focus, in our view, should be much more on how we reduce emissions from the oil and gas value chain and less on actually trying to phase out these fuels entirely.”

The memo calls for a variety of technocratic fixes to America’s LNG policy, largely to meet demand for “cleaner” LNG — i.e. LNG produced with less methane leakage — from American allies in Europe and East Asia. That “will require significant efforts beyond just voluntary industry engagement,” according to the Third Way memo.

These efforts include federal programs to track methane emissions, which the Trump administration has sought to defund (or simply not fund); setting emissions standards with Europe, Japan, and South Korea; and more funding for methane tracking and mitigation programs.

But the memo goes beyond just a few policy suggestions. Third Way sees it as part of an effort to reorient how the Democratic Party approaches fossil fuel policy while still supporting new clean energy projects and technology. (Third Way is also an active supporter of nuclear power and renewables.)

“We don’t want to see Democrats continuing to slow down oil and gas infrastructure and reinforce this narrative that Democrats are just a party of red tape when these projects inevitably go forward anyway, just several years delayed,” Hebert told me. “That’s what we saw during the Biden administration. We saw that pause of approvals of new LNG export terminals and we didn’t really get anything for it.”

Whether the Democratic Party has any interest in going along remains to be seen.

When center-left commentator Matthew Yglesias wrote a New York Times op-ed calling for Democrats to work productively with the domestic oil and gas industry, influential Democratic officeholders such as Illinois Representative Sean Casten harshly rebuked him.

Concern over high electricity prices has made some Democrats a little less focused on pursuing the largest possible reductions in emissions and more focused on price stability, however. New York Governor Kathy Hochul, for instance, embraced an oft-rejected natural gas pipeline in her state (possibly as part of a deal with the Trump administration to keep the Empire Wind 1 project up and running), for which she was rewarded with the Times headline, “New York Was a Leader on Climate Issues. Under Hochul, Things Changed.”

Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro (also a Democrat) was willing to cut a deal with Republicans in the Pennsylvania state legislature to get out of the Northeast’s carbon emissions cap and trade program, which opponents on the right argued could threaten energy production and raise prices in a state rich with fossil fuels. He also made a point of working with the White House to pressure the region’s electricity market, PJM Interconnection, to come up with a new auction mechanism to bring new data centers and generation online without raising prices for consumers.

Ruben Gallego, a Democratic Senator from Arizona (who’s also doing totally normal Senate things like having town halls in the Philadelphia suburbs), put out an energy policy proposal that called for “ensur[ing] affordable gasoline by encouraging consistent supply chains and providing funding for pipeline fortification.”

Several influential Congressional Democrats have also expressed openness to permitting reform bills that would protect oil and gas — as well as wind and solar — projects from presidential cancellation or extended litigation.

As Democrats gear up for the midterms and then the presidential election, Third Way is encouraging them to be realistic about what voters care about when it comes to energy, jobs, and climate change.

“If you look at how the Biden administration approached it, they leaned so heavily into the climate message,” Hebert said. “And a lot of voters, even if they care about climate, it’s just not top of mind for them.”