You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

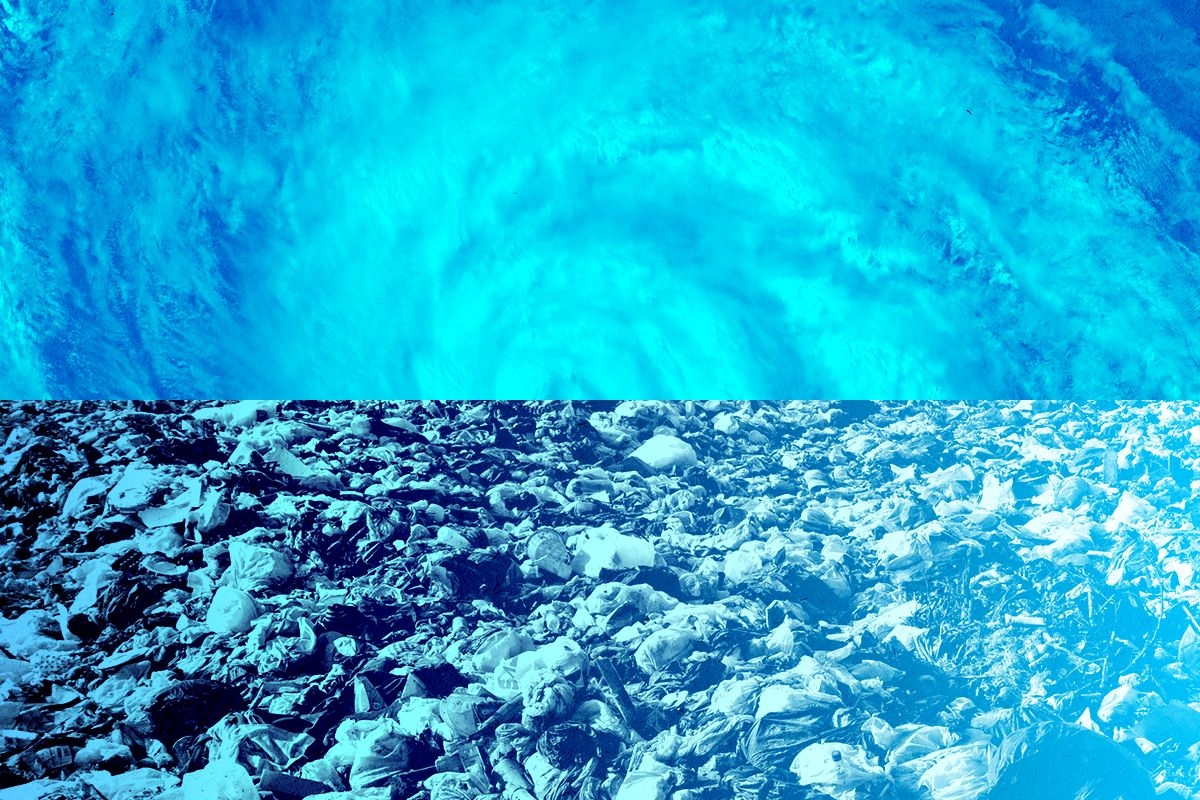

The trash mostly stays put, but the methane is another story.

In the coming days and weeks, as Floridians and others in storm-ravaged communities clean up from Hurricane Milton, trucks will carry all manner of storm-related detritus — chunks of buildings, fences, furniture, even cars — to the same place all their other waste goes: the local landfill. But what about the landfill itself? Does this gigantic trash pile take to the air and scatter Dorito bags and car parts alike around the surrounding region?

No, thankfully. As Richard Meyers, the director of land management services at the Solid Waste Authority of Palm Beach County, assured me, all landfill waste is covered with soil on “at least a weekly basis,” and certainly right before a hurricane, preventing the waste from being kicked up. “Aerodynamically, [the storm is] rolling over that covered waste. It’s not able to blow six inches of cover soil from the top of the waste.”

But just because a landfill won’t turn into a mass of airborne dirt and half-decomposed projectiles doesn’t mean there’s nothing to worry about. Because landfills — especially large ones — often contain more advanced infrastructure such as gas collection systems, which prevent methane from being vented into the atmosphere, and drainage systems, which collect contaminated liquid that’s pooled at the bottom of the waste pile and send it off for treatment. Meyers told me that getting these systems back online after a storm if they’ve been damaged is “the most critical part, from our standpoint.”

A flood-inundated gas collection system can mean more methane escaping into the air, and storm-damaged drainage pipes can lead to waste liquids leaking into the ground and potentially polluting water sources. The latter was a major concern in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria destroyed a landfill’s waste liquid collection system in the Municipality of Juncos in 2017.

As for methane, calculating exactly how much could be released as a result of a dysfunctional landfill gas collection system requires accounting for myriad factors such as the composition of the waste and the climate that it’s in, but the back of the envelope calculations don’t look promising. The Southeast County Landfill near Tampa, for instance, emitted about 100,000 metric tons of CO2 equivalent in 2022, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (although a Harvard engineering study from earlier this year suggests that this may be a significant underestimate). The EPA estimates that gas collection systems are about 75% effective, which means that the landfill generates a total of about 400,000 metric tons of CO2-worth of methane. If Southeast County Landfill’s gas collection system were to go down completely for even a day, that would mean extra methane emissions of roughly 822 metric tons of CO2 equivalent. That difference amounts to the daily emissions of more than 65,000 cars.

That’s a lot of math. But the takeaway is: Big landfills in the pathway of a destructive storm could end up spewing a lot of methane into the atmosphere. And keep in mind that these numbers are just for one hypothetical landfill with a gas collection system that goes down for one day. The emissions numbers, you can imagine, start to look much worse if you consider the possibility that floodwaters could impede access to infrastructure for even longer.

So stay strong out there, landfills of Florida. You may not be the star of this show, but you’ve got our attention.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

A new PowerLines report puts the total requested increases at $31 billion — more than double the number from 2024.

Utilities asked regulators for permission to extract a lot more money from ratepayers last year.

Electric and gas utilities requested almost $31 billion worth of rate increases in 2025, according to an analysis by the energy policy nonprofit PowerLines released Thursday morning, compared to $15 billion worth of rate increases in 2024. In case you haven’t already done the math: That’s more than double what utilities asked for just a year earlier.

Utilities go to state regulators with its spending and investment plans, and those regulators decide how much of a return the utility is allowed to glean from its ratepayers on those investments. (Costs for fuel — like natural gas for a power plant — are typically passed through to customers without utilities earning a profit.) Just because a utility requests a certain level of spending does not mean that regulators will approve it. But the volume and magnitude of the increases likely means that many ratepayers will see higher bills in the coming year.

“These increases, a lot of them have not actually hit people's wallets yet,” PowerLines executive director Charles Hua told a group of reporters Wednesday afternoon. “So that shows that in 2026, the utility bills are likely to continue to rise, barring some major, sweeping action.” Those could affect some 81 million consumers, he said.

Electricity prices have gone up 6.7% in the past year, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, outpacing overall prices, which have risen 2.7%. Electricity is 37% more expensive today than it was just five years ago, a trend researchers have attributed to geographically specific factors such as costs arising from wildfires attributed to faulty utility equipment, as well as rising costs for maintaining and building out the grid itself.

These rising costs have become increasingly politically contentious, with state and local politicians using electricity markets and utilities as punching bags. Newly elected New Jersey Governor Mikie Sherrill’s first two actions in office, for instance, were both aimed at effecting a rate freeze proposal that was at the center of her campaign.

But some of the biggest rate increase requests from last year were not in the markets best known for high and rising prices: the Northeast and California. The Florida utility Florida Power and Light received permission from state regulators for $7 billion worth of rate increases, the largest such increase among the group PowerLines tracked. That figure was negotiated down from about $10 billion.

The PowerLines data is telling many consumers something they already know. Electricity is getting more expensive, and they’re not happy about it.

“In a moment where affordability concerns and pocketbook concerns remain top of mind for American consumers, electricity and gas are the two fastest drivers,” Hua said. “That is creating this sense of public and consumer frustration that we're seeing.”

A federal judge in Massachusetts ruled that construction on Vineyard Wind could proceed.

The Vineyard Wind offshore wind project can continue construction while the company’s lawsuit challenging the Trump administration’s stop work order proceeds, judge Brian E. Murphy for the District of Massachusetts ruled on Tuesday.

That makes four offshore wind farms that have now won preliminary injunctions against Trump’s freeze on the industry. Dominion Energy’s Coastal Virginia offshore wind project, Orsted’s Revolution Wind off the coast of New England, and Equinor’s Empire Wind near Long Island, New York, have all been allowed to proceed with construction while their individual legal challenges to the stop work order play out.

The Department of the Interior attempted to pause all offshore wind construction in December, citing unspecified “national security risks identified by the Department of War.” The risks are apparently detailed in a classified report, and have been shared neither with the public nor with the offshore wind companies.

Vineyard Wind, a joint development between Avangrid Renewables and Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners, has been under construction since 2021, and is already 95% built. More than that, it’s sending power to Massachusetts customers, and will produce enough electricity to power up to 400,000 homes once it’s complete.

In court filings, the developer argued it was urgent the stop work order be lifted, as it would lose access to a key construction boat required to complete the project on March 31. The company is in the process of replacing defective blades on its last handful of turbines — a defect that was discovered after one of the blades broke in 2024, scattering shards of fiberglass into the ocean. Leaving those turbine towers standing without being able to install new blades created a safety hazard, the company said.

“If construction is not completed by that date, the partially completed wind turbines will be left in an unsafe condition and Vineyard Wind will incur a series of financial consequences that it likely could not survive,” the company wrote. The Trump administration submitted a reply denying there was any risk.

The only remaining wind farm still affected by the December pause on construction is Sunrise Wind, a 924-megawatt project being developed by Orsted and set to deliver power to New York State. A hearing for an injunction on that order is scheduled for February 2.

The Secretary of Energy announced the cuts and revisions on Thursday, though it’s unclear how many are new.

The Department of Energy announced on Thursday that it has eliminated nearly $30 billion in loans and conditional commitments for clean energy projects issued by the Biden administration. The agency is also in the process of “restructuring” or “revising” an additional $53 billion worth of loans projects, it said in a press release.

The agency did not include a list of affected projects and did not respond to an emailed request for clarification. However the announcement came in the context of a 2025 year-in-review, meaning these numbers likely include previously-announced cancellations, such as the $4.9 billion loan guarantee for the Grain Belt Express transmission line and the $3 billion partial loan guarantee to solar and storage developer Sunnova, which were terminated last year.

The only further detail included in the press release was that some $9.5 billion in funding for wind and solar projects had been eliminated and was being replaced with investments in natural gas and building up generating capacity in existing nuclear plants “that provide more affordable and reliable energy for the American people.”

A preliminary review of projects that may see their financial backing newly eliminated turned up four separate efforts to shore up Puerto Rico’s perennially battered grid with solar farms and battery storage by AES, Pattern Energy, Convergent Energy and Power, and Inifinigen. Those loan guarantees totalled about $2 billion. Another likely candidate is Sunwealth’s Project Polo, which closed a $289.7 million loan guarantee during the final days of Biden’s tenure to build solar and battery storage systems at commercial and industrial sites throughout the U.S. None of the companies responded to questions about whether their loans had been eliminated.

Moving forward, the Office of Energy Dominance Financing — previously known as the Loan Programs Office — says it has $259 billion in available loan authority, and that it plans to prioritize funding for nuclear, fossil fuel, critical mineral, geothermal energy, grid and transmission, and manufacturing and transportation projects.

Under Trump, the office has closed three loan guarantees totalling $4.1 billion to restart the Three Mile Island nuclear plant, upgrade 5,000 miles of transmission lines, and restart a coal plant in Indiana.