You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

The average anti-wind farm protest is made up of just 23 people.

All across North America, more and more wind farm projects are meeting local opposition.

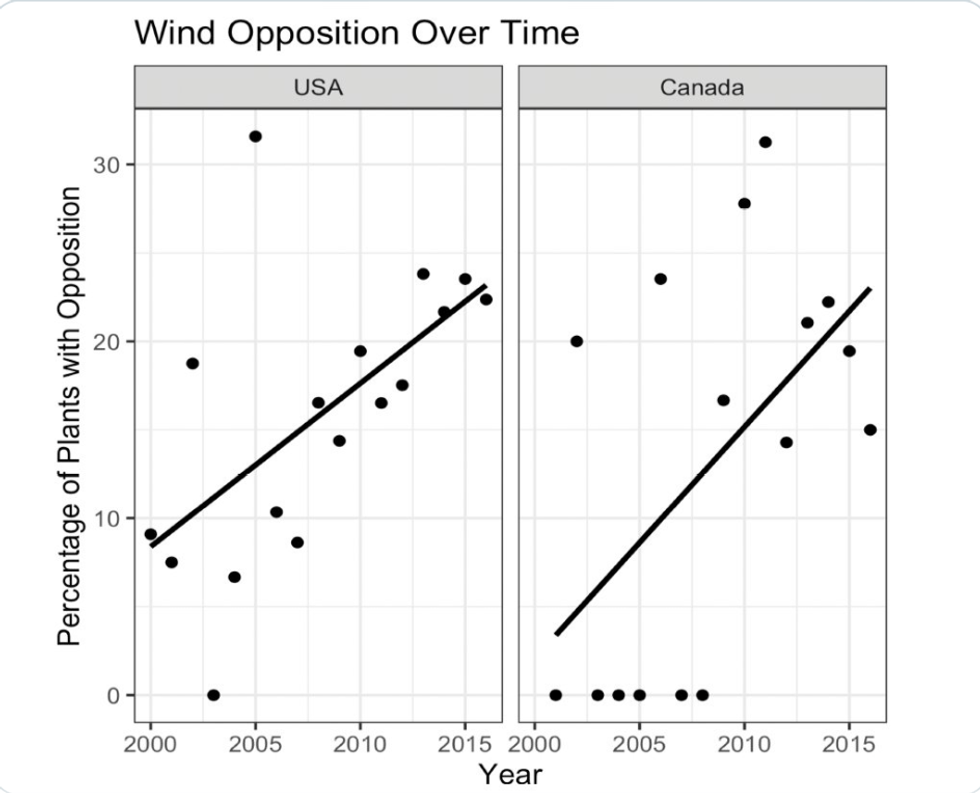

That’s the conclusion of a new study, published earlier this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, that looked at more than 1,400 wind farms proposed in the United States and Canada. The authors found that from 2000 to 2016, local opposition to proposed wind farms got successively worse in both countries.

“In the early 2000s, only around 1 in 10 wind projects was opposed. In 2016, it was closer to one in four,” Leah Stokes, an author of the study and a political-science professor at the University of California at Santa Barbara, wrote on the social network X.

The opposition has probably only gotten worse since then, she added.

Although the study stopped in 2016, a few things stand out about its findings that remain useful to climate debates today.

First, the mechanism of the protests differed between the countries. While Canadians tended to oppose projects by holding physical protests, Americans sought recourse in the courts, using local and federal permitting and environmental rules to block the wind proposals. “In the United States, courts were the dominant mode of opposition, followed by legislation, then physical protest, then letters to the editor,” the authors write.

Second, few of the protests were very large. In the United States, the median anti-wind-farm protest was made up of just 23 people — barely enough to fill a kindergarten classroom. Only about 30 people made up the average Canadian protests. Many of these protests happened in richer, whiter areas, including in the Northeastern United States.

Stokes and her colleagues conclude that reveals what they call “energy privilege,” the ability of rich, largely white communities to stymie the energy transition. By slowing down or blocking wind farms, these protests keep fossil-fuel infrastructure operating for longer, they write. And since that old, dirty infrastructure is often located in poorer or marginalized communities, these protests essentially subject low-income and nonwhite people to more pollution for longer. (That’s the “privilege” part of “energy privilege.”)

I think that’s an important idea, but I would take it one step further. In her X thread, Stokes compared the tiny number of people who make up the anti-wind protests to the more than 50,000 climate activists who filled the streets of New York earlier this month. The anti-renewable movement is small, in other words, while the pro-climate movement is big.

But that mismatch reveals a more profound question about our environmental laws than progressives are always eager to address: How can fewer than two dozen people block a wind farm in the first place? Recent economic research and reporting has shown that the community input process — that is, the meeting-based process at the center of national and local permitting decisions — inherently benefits whiter and wealthier people. And that injustice only gets worse when the threat of a lawsuit is involved.

Get one great climate story in your inbox every day:

That’s because the community-input process exists to serve only those who have the time, money, and expertise to stage a rebellion. You can see that in Washington, D.C., where whiter and wealthier neighborhoods have been able to slow down the construction of affordable housing at a much higher pace than majority Black neighborhoods. Or you can see it in California, where residents have been able to use a state environmental law to block solar farms, public transit, and denser housing. Nevermind “energy privilege” — this is just “permitting privilege.”

Even worse, the longer that a given permitting fight lasts, the more the public seems to grow skeptical of the project in question. In New Jersey, for instance, most people supported the creation of an offshore wind industry for years. But as local fights over the industry grew in salience, and as outside money poured in, the public has soured on the proposal. Today, four in 10 New Jersey residents oppose building new offshore wind farms, according to a recent Monmouth University poll.

There may even be something about the community input that favors opponents of new infrastructure. In 2017, three Boston University economists found that the community-input process may attract people who want to block projects; on average, only 14.6% of people who show up to community meetings tend to favor a given project. That systematic privilege of the status quo is an existential problem for the climate movement. Remember: If the world is to stave off 1.5 degrees Celsius of climate change, it must build new infrastructure at an unprecedented scale.

This amounts to a profound crisis. Right now, America’s legal system gives wealthier, whiter communities — and a very persuasive fossil-fuel industry — a veto to block the clean-energy transition. It’s well past time for climate advocates to ask: Is that democratic? And if it isn’t, what should we do about it?

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

“I believe the tariff on copper — we’re going to make it 50%.”

President Trump announced Tuesday during a cabinet meeting that he plans to impose a hefty tax on U.S. copper imports.

“I believe the tariff on copper — we’re going to make it 50%,” he told reporters.

Copper traders and producers have anticipated tariffs on copper since Trump announced in February that his administration would investigate the national security implications of copper imports, calling the metal an “essential material for national security, economic strength, and industrial resilience.”

Trump has already imposed tariffs for similarly strategically and economically important metals such as steel and aluminum. The process for imposing these tariffs under section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 involves a finding by the Secretary of Commerce that the product being tariffed is essential to national security, and thus that the United States should be able to supply it on its own.

Copper has been referred to as the “metal of electrification” because of its centrality to a broad array of electrical technologies, including transmission lines, batteries, and electric motors. Electric vehicles contain around 180 pounds of copper on average. “Copper, scrap copper, and copper’s derivative products play a vital role in defense applications, infrastructure, and emerging technologies, including clean energy, electric vehicles, and advanced electronics,” the White House said in February.

Copper prices had risen around 25% this year through Monday. Prices for copper futures jumped by as much as 17% after the tariff announcement and are currently trading at around $5.50 a pound.

The tariffs, when implemented, could provide renewed impetus to expand copper mining in the United States. But tariffs can happen in a matter of months. A copper mine takes years to open — and that’s if investors decide to put the money toward the project in the first place. Congress took a swipe at the electric vehicle market in the U.S. last week, extinguishing subsidies for both consumers and manufacturers as part of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. That will undoubtedly shrink domestic demand for EV inputs like copper, which could make investors nervous about sinking years and dollars into new or expanded copper mines.

Even if the Trump administration succeeds in its efforts to accelerate permitting for and construction of new copper mines, the copper will need to be smelted and refined before it can be used, and China dominates the copper smelting and refining industry.

The U.S. produced just over 1.1 million tons of copper in 2023, with 850,000 tons being mined from ore and the balance recycled from scrap, according to United States Geological Survey data. It imported almost 900,000 tons.

With the prospect of tariffs driving up prices for domestically mined ore, the immediate beneficiaries are those who already have mines. Shares in Freeport-McMoRan, which operates seven copper mines in Arizona and New Mexico, were up over 4.5% in afternoon trading Tuesday.

“We had enough assurance that the president was going to deal with them.”

A member of the House Freedom Caucus said Wednesday that he voted to advance President Trump’s “big, beautiful bill” after receiving assurances that Trump would “deal” with the Inflation Reduction Act’s clean energy tax credits – raising the specter that Trump could try to go further than the megabill to stop usage of the credits.

Representative Ralph Norman, a Republican of North Carolina, said that while IRA tax credits were once a sticking point for him, after meeting with Trump “we had enough assurance that the president was going to deal with them in his own way,” he told Eric Garcia, the Washington bureau chief of The Independent. Norman specifically cited tax credits for wind and solar energy projects, which the Senate version would phase out more slowly than House Republicans had wanted.

It’s not entirely clear what the president could do to unilaterally “deal with” tax credits already codified into law. Norman declined to answer direct questions from reporters about whether GOP holdouts like himself were seeking an executive order on the matter. But another Republican holdout on the bill, Representative Chip Roy of Texas, told reporters Wednesday that his vote was also conditional on blocking IRA “subsidies.”

“If the subsidies will flow, we’re not gonna be able to get there. If the subsidies are not gonna flow, then there might be a path," he said, according to Jake Sherman of Punchbowl News.

As of publication, Roy has still not voted on the rule that would allow the bill to proceed to the floor — one of only eight Republicans yet to formally weigh in. House Speaker Mike Johnson says he’ll, “keep the vote open for as long as it takes,” as President Trump aims to sign the giant tax package by the July 4th holiday. Norman voted to let the bill proceed to debate, and will reportedly now vote yes on it too.

Earlier Wednesday, Norman said he was “getting a handle on” whether his various misgivings could be handled by Trump via executive orders or through promises of future legislation. According to CNN, the congressman later said, “We got clarification on what’s going to be enforced. We got clarification on how the IRAs were going to be dealt with. We got clarification on the tax cuts — and still we’ll be meeting tomorrow on the specifics of it.”

Neither Norman nor Roy’s press offices responded to a request for comment.

The state’s senior senator, Thom Tillis, has been vocal about the need to maintain clean energy tax credits.

The majority of voters in North Carolina want Congress to leave the Inflation Reduction Act well enough alone, a new poll from Data for Progress finds.

The survey, which asked North Carolina voters specifically about the clean energy and climate provisions in the bill, presented respondents with a choice between two statements: “The IRA should be repealed by Congress” and “The IRA should be kept in place by Congress.” (“Don’t know” was also an option.)

The responses from voters broke down predictably along party lines, with 71% of Democrats preferring to keep the IRA in place compared to just 31% of Republicans, with half of independent voters in favor of keeping the climate law. Overall, half of North Carolina voters surveyed wanted the IRA to stick around, compared to 37% who’d rather see it go — a significant spread for a state that, prior to the passage of the climate law, was home to little in the way of clean energy development.

But North Carolina now has a lot to lose with the potential repeal of the Inflation Reduction Act, as my colleague Emily Pontecorvo has pointed out. The IRA brought more than 17,000 jobs to the state, per Climate Power, along with $20 billion in investment spread out over 34 clean energy projects. Electric vehicle and charging manufacturers in particular have flocked to the state, with Toyota investing $13.9 billion in its Liberty EV battery manufacturing facility, which opened this past April.

North Carolina Senator Thom Tillis was one of the four co-authors of a letter sent to Majority Leader John Thune in April advocating for the preservation of the law. Together, they wrote that gutting the IRA’s tax credits “would create uncertainty, jeopardizing capital allocation, long-term project planning, and job creation in the energy sector and across our broader economy.” It seems that the majority of North Carolina voters are aligned with their senator — which is lucky for him, as he’s up for reelection in 2026.