You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

It’s not just what they say over the next few weeks — it’s when they say it.

When the Senate returns from recess next week, it will have Trump’s “One Big, Beautiful Bill” to contend with. There’s no doubt the chamber will try to make changes to the omnibus plan to extend and expand Trump’s tax cuts that passed the House last week. The president even told reporters over the weekend that senators should “make the changes they want to make,” and that some of the changes “maybe are something I’d agree with, to be honest.”

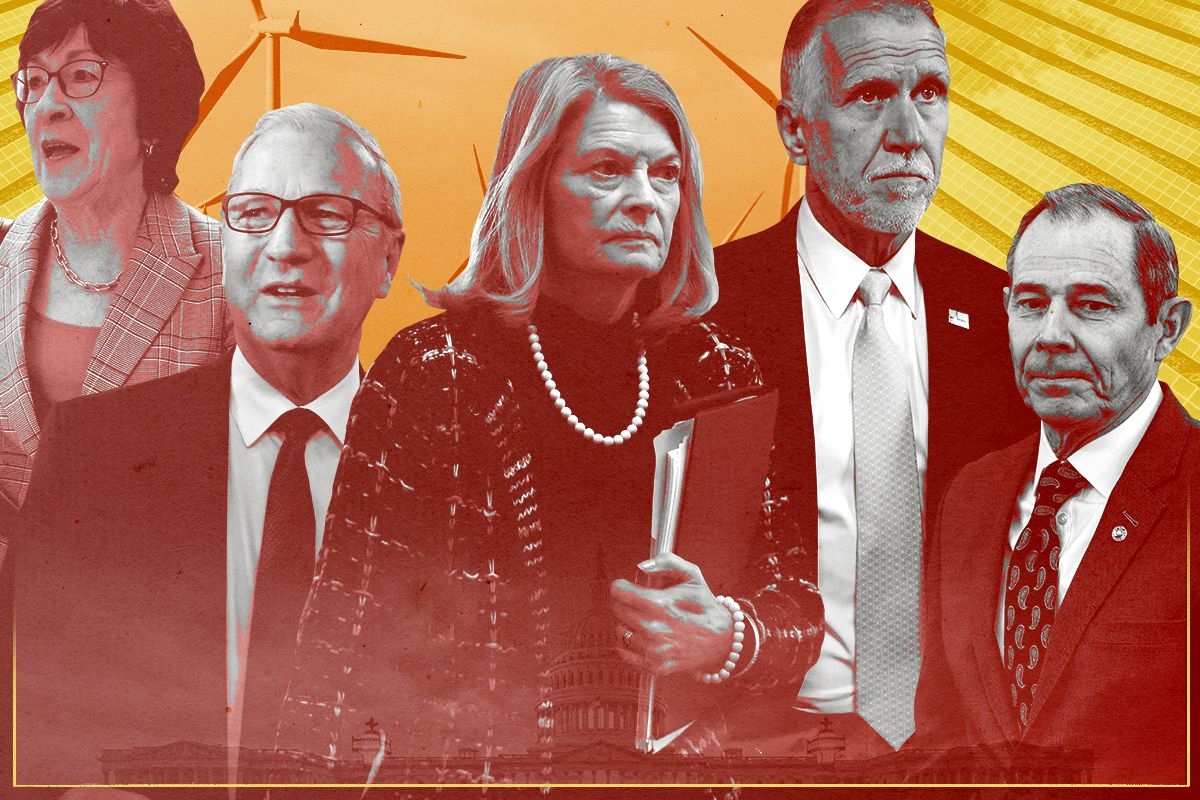

Whether those changes include salvaging the nation’s clean energy tax credits will likely depend on a small group of Republican senators who have criticized the House’s near-total gutting of the subsidies and how much they are willing to fight to undo it.

The bill that passed the House would outright eliminate consumer tax credits for electric vehicles, rooftop solar, and both energy efficiency renovations and new energy-efficient homes. It would also kill the clean hydrogen tax credit at the end of this year and give most zero-carbon power plants, including wind, solar, and geothermal, an end-of-year deadline to start construction, among many other damaging provisions.

To date, at least eight Senate Republicans have spoken out against at least some of these changes, but none of them have tied their vote to the issue. The pressure to stick with your party is “enormous” when your vote is the difference between a bill’s success or failure, Josh Freed, the senior vice president for climate and energy at Third Way, told me. “As we saw in the House, the biggest question is whether any Republican Senator, when push comes to shove, has any willingness to try to stop this bill in order to defend energy tax credits.”

Pay attention to what they say over the next few weeks — and when they say it. It’s one thing to speak out when everything’s still up in the air. It’s quite another to keep talking when votes are on the line.

When the budget fight was first heating up in April, four senators led by Lisa Murkowski of Alaska sent a letter to Majority Leader John Thune warning that repealing the tax credits “would create uncertainty, jeopardizing capital allocation, long-term project planning, and job creation in the energy sector and across our broader economy.” The three co-authors were Thom Tillis of North Carolina, John Curtis of Utah, and Jerry Moran of Kansas.

Last week, after the House modified its proposal to phase out the tax credits more aggressively, Murkowski told Politico the Senate was “obviously going to be looking at” the provisions “as well as the final product, and kind of seeing where we start our conversation.” The moderate Republican has a history of supporting environmental policy, and has already broken with her party on at least one vote this year. In February, she was the only Republican who voted in favor of a Democrat-led effort to reinstate 5,500 federal public lands employees that had been fired by the Department of Government Efficiency. (The legislation failed.) Murkowski has also gone her own way to support more efficient energy codes, loans for electric vehicle manufacturers, and the impeachment of President Trump over the January 6 insurrection. But she did not vote for the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022, and if you look at her overall voting record, these occasions of deviating from the party line have been rare.

Tillis, who is a member of the Finance Committee and will therefore be directly involved in writing the tax credit portion of the bill, has made more specific comments. He said he would push to wind down the tax credits more slowly to give businesses more time to prepare. “We have a lot of work that we need to do on the timeline and scope of the production and investment tax credits,” he told Politico in the same article.

While Tillis does not have the same kind of track record as Murkowski, he’s up for re-election next year, and his state has a lot to lose. Some 34 clean energy projects worth $20 billion in investment and tied to more than 17,000 jobs came to North Carolina because of the tax credits, according to the advocacy group Climate Power. Toyota invested in an EV battery manufacturing plant and just started production last month. Several EV charger manufacturers are setting up shop in the state. Siemens Energy is building a factory to make large power transformers, equipment that is essential to expanding the grid and is currently in very tight supply.

Curtis has also continued to rally around the tax credits. He attended a press conference for Fluence, an energy storage company, back in Utah where he told the Deseret News on Tuesday that the House’s changes to the subsidies were “a problem for the future” of energy. “And I think if I have anything to say about it, I’ll make sure that we’re taking into account our energy future,” he said.

When it became clear that the House was considering changes that would effectively repeal the clean energy tax credits in the IRA, Senators Kevin Cramer and John Hoeven of North Dakota, and Shelley Moore Capito of West Virginia chimed in to voice their concerns. Cramer criticized new deadlines the House proposed for ending the tax credits, telling Politico that “it’s too short for truly new technologies. We’ll have to change that. I don’t think it’s fair to treat an emerging technology the same as a 30-year-old technology.”

After the bill passed the House, Jon Husted of Ohio decided it was time to speak up. “You have companies that have already made investments, made commitments,” he told the outlet NOTUS. “Supply chains have been built around them, and we need to phase that out more slowly. I think that they deserve to have at least five years of that credit.” Like Tillis, Husted has an election coming up — and 35 clean energy projects in his state to protect.

The D.C. insiders I spoke to mentioned a few other powerful senators who could play a role in the debate who’ve been mum on the IRA so far. Thune, of South Dakota, has a history of being friendly toward tax credits for wind energy, and was honored by the American Council on Renewable Energy for his support for renewable energy in 2019. Lindsey Graham, chair of the Budget Committee, has also long been a sometimes-ally for climate action in the Senate. His home state of South Carolina has been one of the biggest beneficiaries of the tax credits, with some 43 projects and 22,000 jobs at risk.

Susan Collins also came up repeatedly as one to watch, despite her not saying much of anything publicly about the tax credit changes yet. Collins is up for re-election next year, and while the IRA hasn’t spurred much manufacturing in Maine, it has driven a clean energy boom. The Maine Climate Labor Council, a coalition of unions, estimates there are 145 utility-scale clean energy projects that are either operating or in development that could be eligible for the tax credits. The state has also made a big energy efficiency push in recent years, with the tax credits supporting the expansion of efficiency jobs.

Then there are the potential spoilers. Republicans can only afford to lose three votes on the bill in order to send it back to the House and ultimately to the President’s desk, and the party has already split into a number of factions looking for various tweaks. Some, like Josh Hawley of Missouri, oppose the legislation’s deep cuts to Medicaid. Meanwhile, fiscal conservatives like Ron Johnson of Wisconsin have said they will push to reduce spending even more.

In the House, defenders of the tax credits ultimately cared more about raising the limit on the state and local tax deduction than fighting for clean energy subsidies. We could see a similar dynamic play out in the Senate, where Murkowski and Collins have also expressed concern about cuts to Medicaid. The Senate also can’t afford to change the bill so much that it will lose support in the House, so any changes will have to be surgical. The calculation will be, “What is the smallest thing that the authors of the bill can give these folks to fall back into line so that it is relatively easy to both pass the Senate and then get back through the House?” Freed explained.

Cramer, for his part, is not coming to the rescue for wind and solar, but he may be able to revive support for other forms of clean energy. The North Dakota Senator wrote a letter to Republican leaders in early May railing against the “indefinite entitlement” given to energy sources that depend on the wind and sun, and arguing that the tax credits should prioritize electricity generators on the basis of “reliability,” so as to encourage “geothermal, hydropower, coal and natural gas with carbon capture, and nuclear without excluding wind and solar.”

Capito has barely made a fuss about the energy credits, but she and Cramer will be the ones to watch to see how the Senate deals with the bill’s provision to repeal the Environmental Protection Agency’s greenhouse gas limits for vehicles, as both sit on the Environment and Public Works Committee, of which Capito is the chair. The repeal may not be allowed under the Senate’s rules for budget reconciliation, as it doesn’t have a direct effect on the federal budget. The Senate Parliamentarian hasn’t yet weighed in, but a negative ruling did not stop the two Republicans from leading the fight to revoke waivers granted to California that allowed it to set pollution limits on cars and trucks.

In the end, if any of these Senators wants to take a stand for big changes to the tax credits, they are going to need at least three colleagues to stick it out with them. A more likely outcome, Freed told me, is for them to attempt some smaller adjustments.

“Hopefully they can make it better, but they’re also under enormous pressure to not deviate too significantly from what the House wrote,” he said. “We just need to go in clear-eyed that it's going to be difficult.”

Editor’s note: A previous version of this article misidentified one of the signatories of the letter to Senate Majority Leader John Thune. It’s been corrected. We regret the error.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Boosters say that the energy demand from data centers make VPPs a necessary tool, but big challenges still remain.

The story of electricity in the modern economy is one of large, centralized generation sources — fossil-fuel power plants, solar farms, nuclear reactors, and the like. But devices in our homes, yards, and driveways — from smart thermostats to electric vehicles and air-source heat pumps — can also act as mini-power plants or adjust a home’s energy usage in real time. Link thousands of these resources together to respond to spikes in energy demand or shift electricity load to off-peak hours, and you’ve got what the industry calls a virtual power plant, or VPP.

The theoretical potential of VPPs to maximize the use of existing energy infrastructure — thereby reducing the need to build additional poles, wires, and power plants — has long been recognized. But there are significant coordination challenges between equipment manufacturers, software platforms, and grid operators that have made them both impractical and impracticable. Electricity markets weren’t designed for individual consumers to function as localized power producers. The VPP model also often conflicts with utility incentives that favor infrastructure investments. And some say it would be simpler and more equitable for utilities to build their own battery storage systems to serve the grid directly.

Now, however, many experts say that VPPs’ time to shine is nigh. Homeowners are increasingly pairing rooftop solar with home batteries, installing electric heat pumps, and buying EVs — effectively large batteries on wheels. At the same time, the ongoing data center buildout has pushed electricity demand growth upward for the first time in decades, leaving the industry hungry for new sources of cheap, clean, and quickly deployable power.

“VPPs have been waiting for a crisis and cash to scale and meet the moment. And now we have both,” Mark Dyson, a managing director at RMI, a clean energy think tank, told me. “We have a load growth crisis, and we have a class of customers who have a very high willingness to pay for power as quickly as possible.” Those customers are the data center hyperscalers, of course, who are impatient to circumvent the lengthy grid interconnection queue in any way possible, potentially even by subsidizing VPP programs themselves.

Jigar Shah, former director of the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office under President Biden, is a major VPP booster, calling their scale-up “the fastest and most cost-effective way to support electrification” in a 2024 DOE release announcing a partnership to integrate VPPs onto the electric grid. While VPPs today provide roughly 37.5 gigawatts of flexible capacity, Shah’s goal was to scale that to between 80 and160 gigawatts by 2030. That’s equivalent to around 7% to 13% of the U.S.’s current utility-scale electricity generating capacity.

Utilities are infamously slow to adopt new technologies. But Apoorv Bhargava, CEO and co-founder of the utility-focused VPP software platform WeaveGrid, told me that he’s “felt a sea change in how aware utilities are that, building my way out is not going to happen; burning my way out is not going to happen.” That’s led, he explained, to an industry-wide recognition that “we need to get much better at flexing resources — whether that’s consumer resources, whether that’s utility-cited resources, whether that’s hyperscalers even. We’ve got to flex.”

Actual VPP capacity appears to have grown more slowly over the past few years than the enthusiasm surrounding the resource’s potential. According to renewable energy consultancy WoodMackenzie, while the number of new VPP programs, offtakers, and company deployments each grew over 33% last year, capacity grew by a more modest 13.7%. Ben Hertz-Shargel, who leads a WoodMac research team focused on distributed energy resources, attributed this slower growth to utility pilot programs that cap VPP participation, rules that limit financial incentives by restricting how VPP capacity is credited, and other market barriers that make it difficult for customers to engage.

Dyson similarly said he sees “friction on the utility side, on the regulatory side, to align the incentive programs with real needs.” These points of friction include requirements for all participating devices to communicate real-time performance data — even for minor, easily modeled metrics such as a smart thermostat’s output — as well as utilities’ hesitancy to share household-level metering data with third parties, even when it’s necessary to enroll in a VPP program. Figuring out new norms for utilities and state regulations is “the nut that we have to crack,” he said.

One of the more befuddling aspects of the whole VPP ecosystem, however, can be just trying to parse out what services a VPP program can actually provide. The term VPP can refer to anything from decades-old demand response programs that have customers manually shutting off appliances during periods of grid stress to aspirational, fully integrated systems that continually and automatically respond to the grid’s needs.

“When a customer like a utility says, I want to do a VPP, nobody knows what they’re talking about. And when a regulator says we should enable VPPs, nobody knows what services they’re selling,” Bhargava told me.

In an effort to help clarify things, the software company EnergyHub developed what it calls the VPP Maturity Model, which defines five levels of maturity. Level 0 represents basic demand response. A utility might call up an industrial customer and tell them to reduce their load, or use price signals to encourage households to cut down on electricity use in the evening. Level 1 incorporates smart devices that can send data back to the utility, while at Level 2, VPPs can more precisely ramp load up or down over a period of hours with better monitoring, forecasting, and some partial autonomy — this is where most advanced VPPs are at today.

Moving into Levels 3 and 4 involves more automation, the ability to handle extended grid events, and ultimately full integration with the utility and grid-operator’s systems to provide 24/7 value. The ultimate goal, according to EnergyHub’s model, is for VPPs to operate indistinguishably from conventional power plants, eventually surpassing them in capabilities.

But some question whether imitating such a fundamentally different resource should actually be the end game.

“What we don’t need is a bunch of virtual power plants that are overconstrained to act just like gas plants,” Dyson told me. By trying to engineer “a new technology to behave like an old technology,” he said, grid operators risk overlooking the unique value VPPs can provide — particularly on the distribution grid, which delivers electricity directly to homes and businesses. Here, VPPs can help manage voltage regulation or work to avoid overloads on lines with many distributed resources, such as solar panels — things traditional power plants can’t do because they’re not connected to these local lines.

Still others are frankly dubious of the value of large-scale VPP programs in the first place. “The benefits of virtual power plants, they look really tantalizing on paper,” Ryan Hanna, a research scientist at UC San Diego’s Center for Energy Research told me. “Ultimately, they’re providing electric services to the electric power grid that the power grid needs. But other resources could equally provide those.”

Why not, he posited, just incentivize or require utilities to incorporate battery storage systems at either the transmission or distribution levels into their long-term plans for meeting demand? Large-scale batteries would also help utilities maximize the value of their existing assets and capture many of the other benefits VPPs promise. Plus, they would do it at a “larger size, and therefore a lower unit cost,” Hanna told me.

Many VPP companies would certainly dispute the cost argument, and also note that with grid interconnection queues stretching on for years, VPPs offer a way to deploy aggregated resources far more quickly than building out and connecting new, centralized assets.

But another advantage of Hanna’s utility-led approach, he said, is that the benefits would be shared equally — all customers would see similar savings on their electricity bills as grid-scale batteries mitigate the need for expensive new infrastructure, the cost of which is typically passed on to ratepayers. VPPs, on the other hand, deliver an outsize benefit to the customers incentivized to participate by dint of their neighborhood’s specific needs, and with the cash on hand to invest in resources such as a home battery or an EV.

This echoes a familiar equity argument made about rooftop solar: that the financial benefits accrue only to households that can afford the upfront investment, while the cost of maintaining shared grid infrastructure falls more heavily on non-participants. Except in the case of VPPs, non-participants also stand to benefit — just less — if the programs succeed in driving down system costs and improving grid reliability.

“I may pay Customer A and Customer B may sit on the sidelines,” Matthew Plante, co-founder and president of the VPP operator Voltus, told me. “Customer A gets a direct payment, but customer B’s rates go down. And so everyone benefits, even if not directly.” On the flip side, if the VPP didn’t exist, that would be a lose-lose for all customers.

Plante is certainly not opposed to the idea of utilities building grid-scale batteries themselves, though. Neither he nor anyone else can afford to be picky about the way new capacity comes online right now, he said. “I think we all want to say, what is quickest and most efficient and most economical? And let’s choose that solution. Sometimes it’s got to be both.”

For its part, Voltus is betting that its pathway to scale runs through its recently announced partnership with the U.S. division of Octopus Energy, the U.K.’s largest energy supplier, which provides software to utilities to coordinate distributed energy resources and enroll customers in VPP programs. Together, they plan to build portfolios of flexible capacity for utilities and wholesale electricity markets, areas where Octopus has extensive experience. “So that gives us market access in a much quicker way,” Plante told me.”

At this moment, there’s no customer more motivated than a data center to bring large volumes of clean energy online as quickly as possible, in whatever way possible. Because while data enters themselves can theoretically act as flexible loads, ramping up and down in response to grid conditions, operators would probably rather pay others to be flexible instead.

“Does a data center company ever want to say, okay, I won’t run my training model for a couple hours on the hottest day of the year? They don’t, because it’s worth a lot of money to run that training model 24/7,” Dyson told me. “Instead, the opportunity here is to use the money that generates to pay other people to flex their load, or pay other people to adopt batteries or other resources that can help create headroom on the system.”

Both Plante of Voltus and Bhargava of WeaveGrid confirmed that hyperscalers are excited by the idea of subsidizing VPP programs in one form or another. That could look like providing capital to help customers in a data center’s service territory buy residential batteries or contracts that guarantee a return for VPP aggregators like Voltus. “I think they recognize in us an ability to get capacity unlocked quickly,” Plante told me.

Yet another knot in this whole equation, however, is that even given hyperscalers’ enthusiasm and the maturation of VPP technology, most utilities still lack a natural incentive to support this resource. That’s because investor-owned utilities — which serve approximately 70% of U.S. electricity customers — earn profits primarily by building infrastructure such as power plants and transmission lines, receiving a guaranteed rate of return on that capital investment. Successful VPPs, on the other hand, reduce a utility’s need to build new assets.

The industry is well aware of this fundamental disconnect, though some contend that current load growth ought to quell this concern. Utilities will still need to build significant new infrastructure to meet the moment, Bhargava told me, and are now under intense pressure to expand the grid’s capacity in other ways, as well.

“They cannot build fast enough. There’s not enough copper, there’s not enough transformers, there’s not enough people,” Bhargava explained. VPPs, he expects, will allow utilities to better prioritize infrastructure upgrades that stand to be most impactful, such as building a substation near a data center instead of in a suburb that could be adequately served by distributed resources.

The real question he sees now is, “How do we make our flexibility as good as copper? How do we make people trust in it as much as they would trust in upgrading the system?”

On the real copper gap, Illinois’ atomic mojo, and offshore headwinds

Current conditions: The deadliest avalanche in modern California history killed at least eight skiers near Lake Tahoe • Strong winds are raising the wildfire risk across vast swaths of the northern Plains, from Montana to the Dakotas, and the Southwest, especially New Mexico, Texas, and Oklahoma • Nairobi is bracing for days more of rain as the Kenyan capital battles severe flooding.

Last week, the Environmental Protection Agency repealed the “endangerment finding” that undergirds all federal greenhouse gas regulations, effectively eliminating the justification for curbs on carbon dioxide from tailpipes or smokestacks. That was great news for the nation’s shrinking fleet of coal-fired power plants. Now there’s even more help on the way from the Trump administration. The agency plans to curb rules on how much hazard pollutants, including mercury, coal plants are allowed to emit, The New York Times reported Wednesday, citing leaked internal documents. Senior EPA officials are reportedly expected to announce the regulatory change during a trip to Louisville, Kentucky on Friday. While coal plant owners will no doubt welcome less restrictive regulations, the effort may not do much to keep some of the nation’s dirtiest stations running. Despite the Trump administration’s orders to keep coal generators open past retirement, as Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote in November, the plants keep breaking down.

At the same time, the blowback to the so-called climate killshot the EPA took by rescinding the endangerment finding has just begun. Environmental groups just filed a lawsuit challenging the agency’s interpretation of the Clean Air Act to cover only the effects of regional pollution, not global emissions, according to Landmark, a newsletter tracking climate litigation.

Copper prices — as readers of this newsletter are surely well aware — are booming as demand for the metal needed for virtually every electrical application skyrockets. Just last month, Amazon inked a deal with Rio Tinto to buy America’s first new copper output for its data center buildout. But new research from a leading mineral supply chain analyst suggests the U.S. can meet 145% of its annual demand using raw copper from overseas and domestic mines and from scrap. By contrast, China — the world’s largest consumer — can source just 40% of its copper that way. What the U.S. lacks, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, is the downstream processing capacity to turn raw copper into the copper cathode manufacturers need. “The U.S. is producing more copper than it uses, and is far more self-reliant than China in terms of raw materials,” Benchmark analyst Albert Mackenzie told the Financial Times. The research calls into question the Trump administration’s mineral policy, which includes stockpiling copper from jointly-owned ventures in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and domestically. “Stockpiling metal ores doesn’t help if you don’t have midstream processing,” Stephen Empedocles, chief executive of US lobbying firm Clark Street Associates, told the newspaper.

Illinois generates more of its power from nuclear energy than any other state. Yet for years the state has banned construction of new reactors. Governor JB Pritzker, a Democrat, partially lifted the prohibition in 2023, allowing for development of as-yet-nonexistent small modular reactors. With excitement about deploying large reactors with time-tested designs now building, Pritzker last month signed legislation fully repealing the ban. In his state of the state address on Wednesday, the governor listed the expansion of atomic energy among his administration’s top priorities. “Illinois is already No. 1 in clean nuclear energy production,” he said. “That is a leadership mantle that we must hold onto.” Shortly afterward, he issued an executive order directing state agencies to help speed up siting and construction of new reactors. Asked what he thought of the governor’s move, Emmet Penney, a native Chicagoan and nuclear expert at the right-leaning Foundation for American Innovation, told me the state’s nuclear lead is “an advantage that Pritzker wisely wants to maintain.” He pointed out that the policy change seems to be copying New York Governor Kathy Hochul’s playbook. “The governor’s nuclear leadership in the Land of Lincoln — first repealing the moratorium and now this Hochul-inspired executive order — signal that the nuclear renaissance is a new bipartisan commitment.”

The U.S. is even taking an interest in building nuclear reactors in the nation that, until 1946, was the nascent American empire’s largest overseas territory. The Philippines built an American-made nuclear reactor in the 1980s, but abandoned the single-reactor project on the Bataan peninsula after the Chernobyl accident and the fall of the Ferdinand Marcos dictatorship that considered the plant a key state project. For years now, there’s been a growing push in Manila to meet the country’s soaring electricity needs by restarting work on the plant or building new reactors. But Washington has largely ignored those efforts, even as the Russians, Canadians, and Koreans eyed taking on the project. Now the Trump administration is lending its hand for deploying small modular reactors. The U.S. Trade and Development Agency just announced funding to help the utility MGEN conduct a technical review of U.S. SMR designs, NucNet reported Wednesday.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

Despite the American government’s crusade against the sector, Europe is going all in on offshore wind. For a glimpse of what an industry not thrust into legal turmoil by the federal government looks like, consider that just on Wednesday the homepage of the trade publication OffshoreWIND.biz featured stories about major advancements on at least three projects totaling nearly 5 gigawatts:

That’s not to say everything is — forgive me — breezy for the industry. Germany currently gives renewables priority when connecting to the grid, but a new draft law would give grid operators more discretion when it comes to offshore wind, according to a leaked document seen by Windpower Monthly.

American clean energy manufacturing is in retreat as the Trump administration’s attacks on consumer incentives have forced companies to reorient their strategies. But there is at least one company setting up its factories in the U.S. The sodium-ion battery startup Syntropic Power announced plans to build 2 gigawatts of storage projects in 2026. While the North Carolina-based company “does not reveal where it manufactures its battery systems,” Solar Power World reported, it “does say” it’s establishing manufacturing capacity in the U.S. “We’re making this move now because the U.S. market needs storage that can be deployed with confidence, supported by certification, insurance acceptance, and a secure domestic supply chain,” said Phillip Martin, Syntropic’s chief executive.

For years now, U.S. manufacturers have touted sodium-ion batteries as the next big thing, given that the minerals needed to store energy are more abundant and don’t afford China the same supply-chain advantage that lithium-ion packs do. But as my colleague Katie Brigham covered last April, it’s been difficult building a business around dethroning lithium. New entrants are trying proprietary chemistries to avoid the mistakes other companies made, as Katie wrote in October when the startup Alsym launched a new stationary battery product.

Last spring, Heron Power, the next-generation transformer manufacturer led by a former Tesla executive, raised $38 million in a Series A round. Weeks later, Spain’s entire grid collapsed from voltage fluctuations spurred by a shortage of thermal power and not enough inverters to handle the country’s vast output of solar power — the exact kind of problem Heron Power’s equipment is meant to solve. That real-life evidence, coupled with the general boom in electrical equipment, has clearly helped the sales pitch. On Wednesday, the company closed a $140 million Series B round co-led by the venture giants Andreessen Horowitz and Breakthrough Energy Ventures. “We need new, more capable solutions to keep pace with accelerating energy demand and the rapid growth of gigascale compute,” Drew Baglino, Heron’s founder and chief executive, said in a statement. “Too much of today’s electrical infrastructure is passive, clunky equipment designed decades ago. At Heron we are manifesting an alternative future, where modern power electronics enable projects to come online faster, the grid to operate more reliably, and scale affordably.”

A senior scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy on what Trump has lost by dismantling Biden’s energy resilience strategy.

A fossil fuel superpower cannot sustain deep emissions reductions if doing so drives up costs for vulnerable consumers, undercuts strategic domestic industries, or threatens the survival of communities that depend on fossil fuel production. That makes America’s climate problem an economic problem.

Or at least that was the theory behind Biden-era climate policy. The agenda embedded in major legislation — including the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act — combined direct emissions-reduction tools like clean energy tax credits with a broader set of policies aimed at reshaping the U.S. economy to support long-term decarbonization. At a minimum, this mix of emissions-reducing and transformation-inducing policies promised a valuable test of political economy: whether sustained investments in both clean energy industries and in the most vulnerable households and communities could help build the economic and institutional foundations for a faster and less disruptive energy transition.

Sweeping policy reversals have cut these efforts short. Abandoning the strategy makes the U.S. economy less resilient to the decline of fossil fuels. It also risks sowing distrust among communities and firms that were poised to benefit, complicating future efforts to recommit to the economic policies needed to sustain an energy transition.

This agenda rested on the idea that sustaining decarbonization would require structural changes across the economy, not just cleaner sources of energy. First, in a country that derives substantial economic and geopolitical power from carbon-intensive industries, a durable energy transition would require the United States to become a clean energy superpower in its own right. Only then could the domestic economy plausibly gain, rather than lose, from a shift away from fossil fuels.

Second, with millions of households struggling to afford basic energy services and fossil fuels often providing relatively cheap energy, climate policy would need to ensure that clean energy deployment reduces household energy burdens rather than exacerbates them.

Third, policies would need to strengthen the economic resilience of communities that rely heavily on fossil fuel industries so the energy transition does not translate into shrinking tax bases, school closures, and lost economic opportunity in places that have powered the country for generations.

This strategy to reshape the economy for the energy transition has largely been dismantled under President Trump.

My recent research examines federal support for fossil fuel-reliant communities, assessing President Biden’s stated goal of “revitalizing the economies of coal, oil, gas, and power plant communities.” Federal spending data provides little evidence that these at-risk communities have been effectively targeted. One reason is timing: While legislation authorized unprecedented support, actual disbursements lagged far behind those commitments.

Many of the key policies — including $4 billion in manufacturing tax credits reserved for communities affected by coal closures — took years to move from statutory language to implementation guidance and final project selection. As a result, aside from certain pandemic-era programs, fossil fuel-reliant communities had received limited support by the time Trump took office last year.

Since then, the Trump administration and Congress have canceled projects intended to benefit fossil fuel-reliant regions, including carbon capture and clean hydrogen demonstrations, and discontinued programs designed to help communities access and implement federal funding.

Other elements of the strategy to reduce the country’s vulnerability to fossil fuel decline have fared even worse under the Trump administration. Programs intended to help households access and afford clean energy — most notably the $27 billion Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund — were effectively canceled last year, including attempts to claw back previously awarded funds. More broadly, the rollback of IRA programs with an explicit equity or justice focus leaves lower-income households more exposed to the economic disruptions that can accompany an energy transition.

By contrast, subsidies and grant programs aimed at strengthening the country’s energy manufacturing base have largely survived, including tax credits supporting domestic production of batteries, solar components, and other key technologies. Even so, the investment environment has weakened. Automakers have scaled back planned U.S. battery manufacturing expansions. Clean Investment Monitor data shows annual clean energy manufacturing investments on pace to decline in 2025, after rising sharply from 2022 to 2024. Whatever one believed about the potential to build globally competitive domestic supply chains for the technologies that will power clean energy systems, those prospects have dimmed amid slowing investment and the Trump administration’s prioritization of fossil fuels.

Perhaps these outcomes were unavoidable. Building a strong domestic solar industry was always uncertain, and place-based economic development programs have a mixed track record even under favorable conditions. Still, the Biden-era approach reflected a coherent theory of climate politics that warranted a real-world test.

Over the past year, debates in climate policy circles have centered on whether clean energy progress can continue under less supportive federal policies, with plausible cases made on both sides. The fate of Biden’s broader economic strategy to sustain the energy transition, however, is less ambiguous. The underlying dependence of the United States on fossil fuels across industries, households, and many local communities remains largely unchanged.