You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

They haven’t even been announced yet, but the idea that they will has sent prices soaring.

China, Canada, Mexico, steel, aluminum, cars, and soon, copper. That’s what the market has concluded following a Bloomberg News report last week that copper tariffs would arrive far sooner than the 270 days President Trump gave the Department of Commerce to conduct its investigation into “dumping” of the metal.

Copper has been dubbed the “metal of electrification,” and demand for it is expected to skyrocket under any reasonable scenario to contain global temperature rise. Even according to a U.S. administration that, at best, neglects climate change considerations, copper is an “essential material for national security, economic strength, and industrial resilience,” as the Trump White House said while announcing its investigation into copper imports.

The effort to boost domestic production of copper did not start with this White House, but it has historically run into the same problems that beset the mining industry: New production can take decades to begin, even after you find the minerals you’re looking for underground. And if demand is not assured — if, for instance, subsidies for electric vehicles filled with copper disappear — then investing in new production could lead to bankruptcy, whereas holding back on new capacity would, at worst, mean forgoing some profits.

The Trump administration and the broader energy and foreign policy community have been, in general, obsessed with rocks — critical minerals, rare earths, and other minerals that are indeed “critical” to much of the economy but are not listed as such. Copper sits somewhere between these categories — while it does not appear on the United States Geological Survey list of critical minerals, which ranges from aluminum and antimony to zinc and zirconium, it does appear on the Department of Energy’s list of “critical materials.”

These lists guide federal data collection efforts, and that data can then get used to guide policymaking. Being on these lists doesn’t guarantee that a related program will get funding, but it does mean that the data is there to draw from should someone need to make a case for why their program should get funding.

This gap between the lists has been a target for Congress, especially for legislators in the Southwest, where much of America’s copper is mined. The discrepancies in the list is essentially a matter of focus for the Energy and Interior Departments — with Energy naturally focused on what’s especially important for energy infrastructure. Getting consistency between the lists, which are only a few years old, will “increase transparency within our federal agencies, ensuring all of our nation’s critical resources are developed, traded, and produced equally, and strengthen our supply chains,” Mike Lee (R-Ut), a sponsor of the Senate version of the legislation, said in a statement.

Trump’s executive order asking for the investigation sought to speed up permitting for new mines — and they’ll need all the help they can get. S&P calculates that the average copper mine takes over 30 years to develop. Rio Tinto and BHP’s Resolution Copper project in Superior, Arizona — which the companies hope will produce 20 million tons of copper — has already sucked up some $2 billion of capital while producing zero copper after about 20 years of legal and political opposition. A proposed copper-nickel mine in Minnesota has already absorbed around $1 billion worth of investment and is still wrangling over the more than 20 permits it needs.

But for the Trump administration’s strategy of tariffs and expedited permitting to actually work for American copper end users, it will have to lead to an expansion of smelting and recycling, in addition to mining.

Reuters reported last year that the Mexican conglomerate Grupo Mexico would re-open an Arizona smelter, but that has yet to happen (it’s currently a Superfund site). A copper mine in Milford, Utah said last week that it was expanding to meet rising copper demand.

The smelting sector is dominated by China. “The United States has ample copper reserves, yet our smelting and refining capacity lags significantly behind global competitors,” the White House said in its copper executive order in February. China’s dominance, “coupled with global overcapacity and a single producer’s control of world supply chains, poses a direct threat to United States national security and economic stability.”

The United States produces around 1.2 million tons of copper annually from its mines and imports around 900,000 tons, according to the United States Geological Survey. Some of that domestically mined copper — around 375,000 tons worth — ends up being exported for smelting, according to the Copper Development Association.

While the United States is near the top of national copper production (well behind the world leader, Chile, but comparable to other large-scale copper producers such as Indonesia and Australia), it has a meager copper refining industry, with only two active smelters producing around 400,000 tons of copper a year — a fraction of China’s refining capacity — leaving American industry reliant on imports.

The energy industry has been dealing with the copper issue for years. More specifically, it’s worrying about how domestic and global production will be able to keep up with what forecasters anticipate could be massive demand.

That goes not just for copper — it also includes the metals that are mined alongside it. First Solar, the U.S.-based solar manufacturing company, has benefited from tariffs on solar panels put in place during the Biden administration. But while First Solar has been a winner in the renewable energy trade conflict, it is still sensitive to the global trade in commodities. That’s in part because it is also a major consumer of tellurium, a mineral that’s a byproduct of copper mining, and which was the subject of expanded export Chinese export controls announced early last month.

“We have, over the past decade employed a strategic sourcing strategy to diversify our tellurium supply chain to mitigate a sole sourcing position in China and are undertaking additional measures to mitigate dependencies on China for certain products containing to tellurium,” Alexander Bradley, First Solar’s chief financial officer, said in the company’s February earnings call. “While we continue to evaluate [whether] there will be any operational impact from China's decision, this latest development emphasizes the urgent need for the United States to accelerate the strategic development of copper mining and processing of its byproduct materials, including tellurium.”

Electric vehicles are another major user of copper among climate technologies, with EVs having on average around 180 pounds of copper in them, according to the Copper Development Association. Tesla — which will soon be hit by auto tariffs — has been actively trying to reduce its copper consumption. Meanwhile Rivian, one of Tesla’s primary domestic competitors, announced last year that it would cut its production targets dramatically due to what turned out to be a supplier communication snafu for a copper component of its motors.

“We’re very bullish on copper prices,” Kathleen Quirk, chief executive officer of Freeport-McMoRan, which runs a number of U.S. copper mines (and a smelter, to boot), said at a financial conference in February. With boosts in demand coming from “power generation, new power generation investments, multibillion-dollar investments in infrastructure and energy infrastructure, it's going to be very positive for copper.”

Copper prices paid by American manufacturers have been rising for the past five months, according to the monthly PMI survey. Prices in New York reached record highs last week, hitting almost $12,000 per ton as the industry tried to beat the almost-certainly-inevitable tariffs, according to an ING analyst report released last week.

The actual imposition of the tariffs would constitute a “further upside risk to copper prices” — in other words, prices will continue to climb, according to the ING analysts. “The U.S. copper rush could leave the rest of the world tight on copper if demand picks up more quickly than expected,” the ING analysts wrote.

Copper futures have shot up this year by around 25%, leading to profits for those who mine it — especially in the United States.

From the perspective of Freeport-McMoRan, the market gyrations so far have generally been to the upside, with the premium on copper in the U.S. “helping us from that perspective of generating higher revenues for our U.S. price copper,” Quirk said at the conference. But the domestic copper industry as a whole does not see tariffs as the sole way to increase copper production.

“The U.S. will need an all-of-the-above sourcing strategy to secure a stable supply for domestic use. This must include increased mining in the U.S., increased smelting and refining in the U.S., enhanced recycling, keeping more copper scrap within U.S. borders, and continued trade with reliable partners to maintain the flow of critical raw material feedstocks for domestic use,” Copper Development Association chief executive Adam Estelle told me in an emailed statement.

And tariffs can come in faster than new mines and smelters can be built or their capacity expanded. American mining projects have been mired in decades of permitting delays and negotiations with local communities not because there isn’t a market opportunity for new copper, but because it just takes a very long time to open a mine.

Even as she was celebrating Freeport-McMoRan’s robust outlook, CEO Kathleen Quirk noted that “at the same time, it's become more and more difficult to develop new supplies of copper.”

That goes especially for industries related to renewable energy, where copper finds itself into grid equipment, solar panels, and wind turbines. Even so, they’ve been wary of talking about an impending tariff directly.

A number of trade groups, including the Zero Emission Transportation Association, the National Electrical Manufacturers Association, and the Solar Energy Industries Association, hailed an executive order aiming to accelerate critical minerals production released March 20. When I asked about copper tariffs, however, a ZETA spokesperson referred me to an earlier statement decrying trade conflict with Canada and Mexico, saying that “imposing tariffs on allies and trading partners like Canada and Mexico — both of which play a significant role in the North American automotive supply chain — will increase costs to consumers and make it more difficult to attract investment into our communities.”

Meanwhile, NEMA’s vice president of public affairs, Spencer Pederson, told me in an emailed statement that “any new trade policies must provide predictability and certainty for future domestic investments and businesses.”

Other manufacturing-centric industries that use copper aren’t thrilled about the prospect of tariffs, either. A spokesperson for the National Association of Manufacturers referred me to its recent survey showing that the top two concerns among its members were “trade uncertainties,” feared by more than three quarters of respondents, and “increased raw material costs,” which worried 60% of respondents. While NAM is broadly supportive of many Trump administration goals, especially around extending the 2017 tax cuts, it has called for a “commonsense manufacturing strategy” which includes “making way for exemptions for critical inputs.” That runs against the Trump administration’s preference for big, obvious tariffs.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

This week is light on the funding, heavy on the deals.

This week’s Funding Friday is light on the funding but heavy on the deals. In the past few days, electric carmaker Rivian and virtual power plant platform EnergyHub teamed up to integrate EV charging into EnergyHub’s distributed energy management platform; the power company AES signed 20-year power purchase agreements with Google to bring a Texas data center online; and microgrid company Scale acquired Reload, a startup that helps get data centers — and the energy infrastructure they require — up and running as quickly as possible. Even with venture funding taking a backseat this week, there’s never a dull moment.

Ahead of the Rivian R2’s launch later this year, the EV-maker has partnered with EnergyHub, a company that aggregates distributed energy resources into virtual power plants, to give drivers the opportunity to participate in utility-managed charging programs. These programs coordinate the timing and rate of EV charging to match local grid conditions, enabling drivers to charge when prices are low and clean energy is abundant while avoiding periods of peak demand that would stress the distribution grid.

As Seth Frader-Thompson, EnergyHub’s president, said in a statement, “Every new EV on the road is a win for drivers and the environment, and by managing charging effectively, we ensure this growth remains a benefit for the grid as well.”

The partnership will fold Rivian into EnergyHub’s VPP ecosystem, giving the more than 150 utilities on its platform the ability to control when and how participating Rivian drivers charge. This managed approach helps alleviate grid stress, thus deferring the need for costly upgrades to grid infrastructure such as substations or transformers. Extending the lifespan of existing grid assets means lower electricity costs for ratepayers and more capacity to interconnect new large loads — such as data centers.

Google seems to be leaning hard into the “bring-your-own-power” model of data center development as it looks to gain an edge in the AI race.

The latest evidence came on Tuesday, when the power company and utility operator AES announced a partnership with the hyperscaler to provide on-site power for a new data center in Texas. signing 20-year power purchase agreements. AES will develop, own, and operate the generation assets, as well as all necessary electricity infrastructure, having already secured the land and interconnection agreements to bring this new power online. The data center is set to begin operations in 2027.

As of yet, neither company has disclosed the exact type of energy infrastructure that AES will be building, although Amanda Peterson Corio, Google’s head of data center energy, said in a press release that it will be “clean.”

“In partnership with AES, we are bringing new clean generation online directly alongside the data center to minimize local grid impact and protect energy affordability,” she said.

This announcement came the same day the hyperscaler touted a separate agreement with the utility Xcel Energy to power another data center in Minnesota with 1.6 gigawatts of solar and wind generation and 300 megawatts of long-duration energy storage from the iron-air battery startup Form Energy.

The microgrid developer Scale has acquired Reload, a “powered land” startup founded in 2024, for an undisclosed sum. What is “powered land”? Essentially, it’s land that Reload has secured and prepared for large data centers customers, obtaining permits and planning for onsite energy infrastructure such that sites can be energized immediately. This approach helps developers circumvent the years-long utility interconnection queue and builds on Scale’s growing focus on off-grid data center projects, as the company aims to deliver gigawatts of power for hyperscalers in the coming years powered by a diverse mix of sources, from solar and battery storage to natural gas and fuel cells.

Early last year, the Swedish infrastructure investor EQT acquired Scale. The goal, EQT said, was to enable the company “to own and operate billions of dollars in distributed generation assets.” At the time of the acquisition, Scale had 2.5 gigawatts of projects in its pipeline. In its latest press release the company announced it has secured a multi-hundred-megawatt contract with a leading hyperscaler, though it did not name names.

As Jan Vesely, a partner at EQT said in a statement, “By bringing together Reload’s campus development capabilities, Scale’s proven islanded power operating platform, and EQT’s deep expertise across energy, digital infrastructure and technology, we are supporting a more integrated approach to delivering power for next-generation digital infrastructure today.”

Not to say there’s been no funding news to speak of!

As my colleague Alexander C. Kaufman reported in an exclusive on Thursday, fusion company Shine Technologies raised $240 million in a Series E round, the majority of which came from biotech billionaire Patrick Soon-Shiong. Unlike most of its peers, Shine isn’t gunning to build electricity-generating reactors anytime soon. Instead, its initial focus is producing valuable medical isotopes — currently made at high cost via fission — which it can sell to customers such as hospitals, healthcare organizations, or biopharmaceutical companies. The next step, Shine says, is to scale into recycling radioactive waste from spent fission fuel.

“The basic premise of our business is fusion is expensive today, so we’re starting by selling it to the highest-paying customers first,” the company’s CEO, Greg Piefer told Kaufman, calling electricity customers the “lowest-paying customer of significance for fusion today.”

On the solar siege, New York’s climate law, and radioactive data center

Current conditions: A rain storm set to dump 2 inches of rain across Alabama, Tennessee, Georgia, and the Carolinas will quench drought-parched woodlands, tempering mounting wildfire risk • The soil on New Zealand’s North Island is facing what the national forecast called a “significant moisture deficit” after a prolonged drought • Temperatures in Odessa, Texas, are as much as 20 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than average.

For all its willingness to share in the hype around as-yet-unbuilt small modular reactors and microreactors, the Trump administration has long endorsed what I like to call reactor realism. By that, I mean it embraces the need to keep building more of the same kind of large-scale pressurized water reactors we know how to construct and operate while supporting the development and deployment of new technologies. In his flurry of executive orders on nuclear power last May, President Donald Trump directed the Department of Energy to “prioritize work with the nuclear energy industry to facilitate” 5 gigawatts of power uprates to existing reactors “and have 10 new large reactors with complete designs under construction by 2030.” The record $26 billion loan the agency’s in-house lender — the Loan Programs Office, recently renamed the Office of Energy Dominance Financing — gave to Southern Company this week to cover uprates will fulfill the first part of the order. Now the second part is getting real. In a scoop on Thursday, Heatmap’s Robinson Meyer reported that the Energy Department has started taking meetings with utilities and developers of what he said “would almost certainly be AP1000s, a third-generation reactor produced by Westinghouse capable of producing up to 1.1 gigawatts of electricity per unit.”

Reactor realism includes keeping existing plants running, so notch this as yet more progress: Diablo Canyon, the last nuclear station left in California, just cleared the final state permitting hurdle to staying open until 2030, and possibly longer. The Central Coast Water Board voted unanimously on Thursday to give the state’s last nuclear plant a discharge permit and water quality certification. In a post on LinkedIn, Paris Ortiz-Wines, a pro-nuclear campaigner who helped pass a 2022 law that averted the planned 2025 closure of Diablo Canyon, said “70% of public comments were in full support — from Central Valley agricultural associations, the local Chamber of Commerce, Dignity Health, the IBEW union, district supervisors, marine meteorologists, and local pro-nuclear organizations.” Starting in 2021, she said, she attended every hearing on the bill that saved the plant. “Back then, I knew every single pro-nuclear voice testifying,” she wrote. “Now? I’m meeting new ones every hearing.”

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. It was a year of record solar deployments, it was a year of canceled solar megaprojects, choked-off permits, and desperate industry pleas to Congress for help. But the solar industry’s political clouds may be parting. The Department of the Interior is reviewing at least 20 commercial-scale projects that E&E News reported had “languished in the permitting pipeline” since Trump returned to office. “That includes a package of six utility-scale projects given the green light Friday by Interior Secretary Doug Burgum to resume active reviews, such as the massive Esmeralda Energy Center in Nevada,” the newswire reported, citing three anonymous career officials at the agency.

Heatmap’s Jael Holzman broke the news that the project, also known as Esmeralda 7, had been canceled in October. At the time, NextEra, one of the project’s developers, told her that it was “committed to pursuing our project’s comprehensive environmental analysis by working closely with the Bureau of Land Management.” That persistence has apparently paid off. In a post on X linking to the article, Morgan Lyons, the senior spokesperson at the Solar Energy Industries Association, called the change “quite a tone shift” with the eyes emoji. GOP voters overwhelmingly support solar power, a recent poll commissioned by the panel manufacturer First Solar found. The MAGA coalition has some increasingly prominent fans. As I have covered in the newsletter, Katie Miller, the right-wing influencer and wife of Trump consigliere Stephen Miller, has become a vocal proponent of competing with China on solar and batteries.

Get Heatmap AM directly in your inbox every morning:

MP Materials operates the only active rare earths mine in the United States at California’s Mountain Pass. Now the company, of which the federal government became the largest shareholder in a landmark deal Trump brokered earlier this year, is planning a move downstream in the rare earths pipeline. As part of its partnership with the Department of Defense, MP Materials plans to invest more than $1 billion into a manufacturing campus in Northlake, Texas, dedicated to making the rare earth magnets needed for modern military hardware and electric vehicles. Dubbed 10X, the campus is expected to come online in 2028, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

New York’s rural-urban divide already maps onto energy politics as tensions mount between the places with enough land to build solar and wind farms and the metropolis with rising demand for power from those panels and turbines. Keeping the state’s landmark climate law in place and requiring New York to generate the vast majority of its power from renewables by 2040 may only widen the split. That’s the obvious takeaway from data from the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority. In a memo sent Thursday to Governor Kathy Hochul on the “likely costs of” complying with the law as it stands, NYSERDA warned that the statute will increase the cost of heating oil and natural gas. Upstate households that depend on fossil fuels could face hikes “in excess of $4,000 a year,” while New York City residents would see annual costs spike by $2,300. “Only a portion of these costs could be offset by current policy design,” read the memo, a copy of which City & State reporter Rebecca C. Lewis posted on X.

Last fall, this publication’s energy intelligence unit Heatmap Pro commissioned a nationwide survey asking thousands of American voters: “Would you support or oppose a data center being built near where you live?” Net support came out to +2%, with 44% in support and 42% opposed. Earlier this month, the pollster Embold Research ran the exact same question by another 2,091 registered voters across the country. The shift in the results, which I wrote about here, is staggering. This time just 28% said they would support or strongly support a data center that houses “servers that power the internet, apps, and artificial intelligence” in their neighborhood, while 52% said they would oppose or strongly oppose it. That’s a net support of -24% — a 26-point drop in just a few months.

Among the more interesting results was the fact that the biggest partisan gap was between rural and urban Republicans, with the latter showing greater support than any other faction. When I asked Emmet Penney at the right-leaning Foundation for American Innovation to make sense of that for me, he said data centers stoke a “fear of bigness” in a way that compares to past public attitudes on nuclear power.

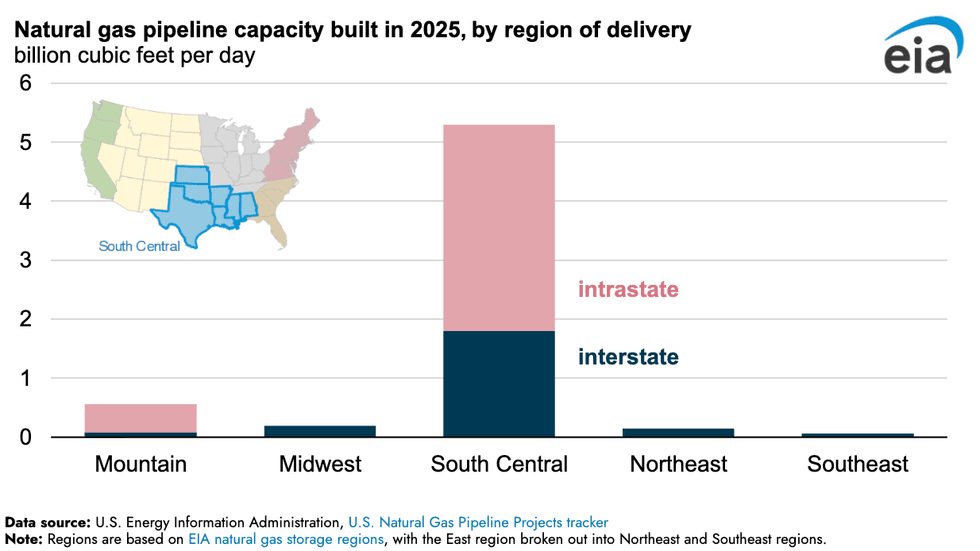

Gas pipeline construction absolutely boomed last year in one specific region of the U.S. Spanning Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama, the so-called South Central bloc saw a dramatic spike in intrastate natural gas pipelines, more than all other regions combined, per new Energy Information Administration data. It’s no mystery as to why. The buildout of liquified natural gas export terminals along the Gulf coast needs conduits to carry fuel from the fracking fields as far west as the Texas Permian.

Rob sits down with Jane Flegal, an expert on all things emissions policy, to dissect the new electricity price agenda.

As electricity affordability has risen in the public consciousness, so too has it gone up the priority list for climate groups — although many of their proposals are merely repackaged talking points from past political cycles. But are there risks of talking about affordability so much, and could it distract us from the real issues with the power system?

Rob is joined by Jane Flegal, a senior fellow at the Searchlight Institute and the States Forum. Flegal was the former senior director for industrial emissions at the White House Office of Domestic Climate Policy, and she has worked on climate policy at Stripe. She was recently executive director of the Blue Horizons Foundation.

Shift Key is hosted by Robinson Meyer, the founding executive editor of Heatmap News.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Here is an excerpt from their conversation:

Robinson Meyer: What’s interesting is the scarcity model is driven by the fact that ultimately rate payers that is utility customers are where the buck stops, and so state regulators don’t want utilities to overbuild for a given moment because ultimately it is utility customers — it’s people who pay their power bills — who will bear the burden of a utility overbuilding. In some ways, the entire restructured electricity market system, the entire shift to electricity markets in the 90s and aughts, was because of this belief that utilities were overbuilding.

And what’s been funny is that, what, we started restructuring markets around the year 2000. For about five or six or seven years. Wall Street was willing to finance new electricity. I mean, I hear two stories here — basically it’s another place where I hear two stories, and I think where there’s a lot of disagreement about the path forward on electricity policy, in that I’ve heard a story that, basically, electricity restructuring starts in the late 90s you know year 2000, and for five years, Wall Street is willing to finance new power investment based entirely on price risk based entirely on the idea that market prices for electricity will go up. Then three things happen: The Great Recession, number one, wipes out investment, wipes out some future demand.

Number two, fracking. Power prices tumble, and a bunch of plays that people had invested in, including then advanced nuclear, are totally out of the money suddenly. Number three, we get electricity demand growth plateaus, right? So for 15 years, electricity demand plateaus. We don’t need to finance investments into the power grid anymore. This whole question of, can you do it on the back of price risk? goes away because electricity demand is basically flat, and different kinds of generation are competing over shares and gas is so cheap that it’s just whittling away.

Jane Flegal: But this is why that paradigm needs to change yet again. Like ,we need to pivot to like a growth model where, and I’m not, again —

Meyer: I think what’s interesting, though, is that Texas is the other counterexample here. Because Texas has had robust load growth for years, and a lot of investment in power production in Texas is financed off price risk, is financed off the assumption that prices will go up. Now, it’s also financed off the back of the fact that in Texas, there are a lot of rules and it’s a very clear structure around finding firm offtake for your powers. You can find a customer who’s going to buy 50% of your power, and that means that you feel confident in your investment. And then the other 50% of your generation capacity feeds into ERCOT. But in some ways, the transition that feels disruptive right now is not only a transition like market structure, but also like the assumptions of market participants about what electricity prices will be in the future.

Flegal: Yeah, and we may need some like backstop. I hear the concerns about the risks of laying early capital risks basically on rate payers in the frame of growth rather than scarcity. But I guess my argument is just there’s ways to deal with that. Like we could come up with creative ways to think about dealing with that. And I’m not seeing enough ideation in that space, which — I would like, again, a call for papers, I guess — that I would really like to get a better handle on.

The other thing that we haven’t talked about, but that I do think, you know, the States Forum, where I’m now a senior fellow, I wrote a piece for them on electricity affordability several months ago now. But one of the things that doesn’t get that much attention is just like getting BS off of bills, basically. So there’s like the rate question, but then there’s the like, what’s in a bill? And like, what, what should or should not be in a bill? And in truth, you know, we’ve got a lot of social programs basically that are being funded by the rate base and not the tax base. And I think there are just like open questions about this — whether it’s, you know, wildfire in California, which I think everyone recognizes is a big challenge, or it’s efficiency or electrification or renewable mandates in blue states. There are a bunch of these things and it’s sort of like there are so few things you can do in the very near term to constrain rate increases for the reasons we’ve discussed.

You can find a full transcript of the episode here.

Mentioned:

Cheap and Abundant Electricity Is Good, by Jane Flegal

From Heatmap: Will Virtual Power Plants Ever Really Be a Thing?

Previously on Shift Key: How California Broke Its Electricity Bills and How Texas Could Destroy Its Electricity Market

This episode of Shift Key is sponsored by …

Accelerate your clean energy career with Yale’s online certificate programs. Explore the 10-month Financing and Deploying Clean Energy program or the 5-month Clean and Equitable Energy Development program. Use referral code HeatMap26 and get your application in by the priority deadline for $500 off tuition to one of Yale’s online certificate programs in clean energy. Learn more at cbey.yale.edu/online-learning-opportunities.

Music for Shift Key is by Adam Kromelow.