You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Inside California’s audacious plan to stash more than a trillion gallons of water underground

The world is slowly but surely running out of groundwater. A resource that for centuries has seemed unending is being lapped up faster than nature can replenish it.

“Globally speaking, there’s a groundwater crisis,” said Michael Kiparsky, director of the Wheeler Water Institute at UC Berkeley’s Center for Law, Energy, and the Environment. “We have treated groundwater as a free and limitless source of water in effect, even as we have learned that it’s not that.”

Aquifers are the porous, sponge-like bodies of rock underground that store groundwater; they can be tapped by wells and discharge naturally at springs or wetlands. Especially in places that have already been hard-hit by climate change, many aquifers have become so depleted that humans need to step in; the Arabian Aquifer in Saudi Arabia and the Murzuk-Djado Basin in North Africa, per a 2015 study, are particularly stressed and have little hope of recharging. In the U.S., aquifers are depleting fast from the Pacific Northwest to the Gulf, but drought-stricken California is the poster-child of both water stress and efforts to undo the damage.

In March, the state approved plans to actively replenish its groundwater after months of being inundated by unexpected levels of rainfall. While this move is not brand-new — the state’s Water Resources Control Board has been structuring water restrictions to encourage enhanced aquifer recharge since 2015 in the brief windows when California has water to spare — the scale of this year’s effort is unprecedented.

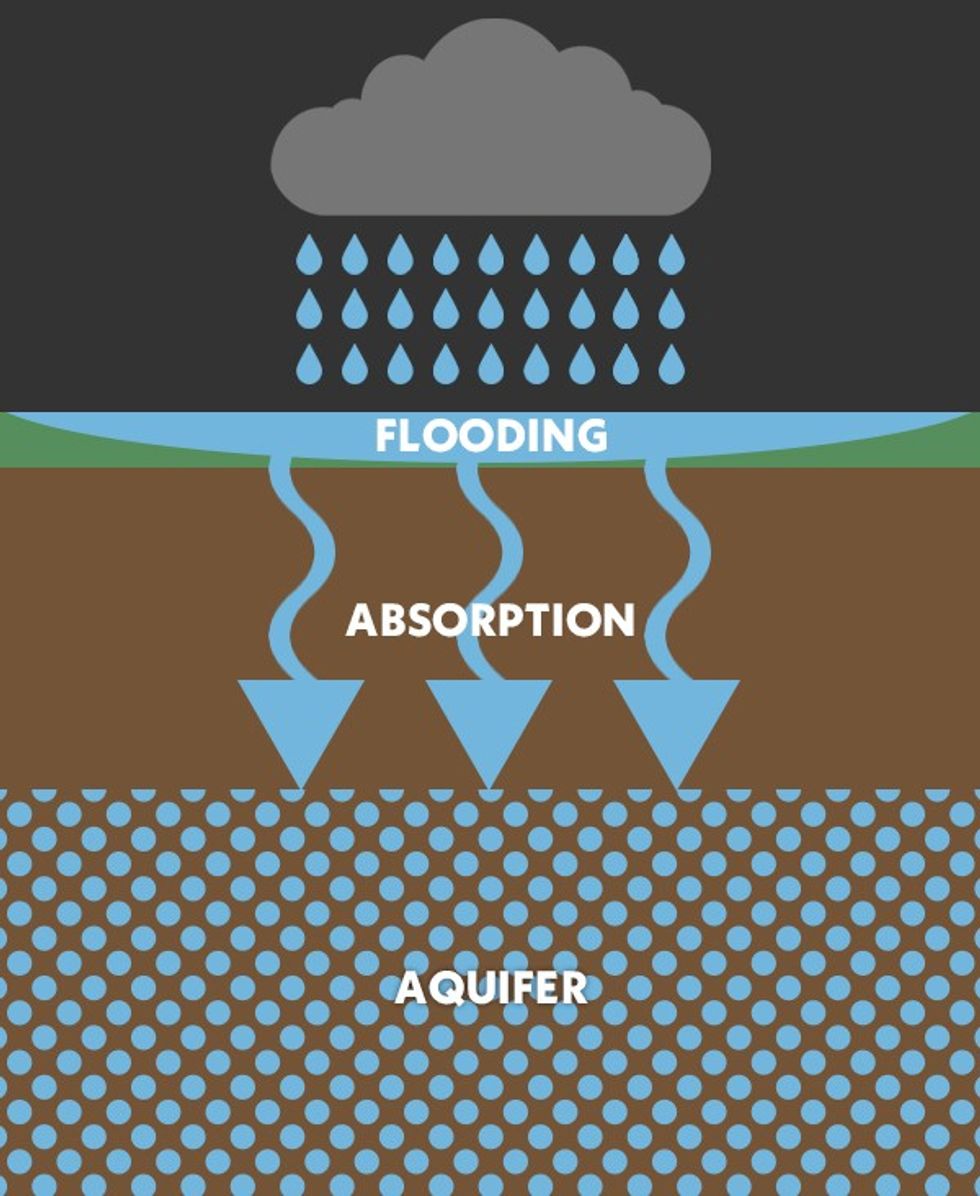

But just how will all that flood water get back underground? California’s approach, which promotes flooding certain fields and letting the water seep down slowly through soil and rocks to the aquifers below, represents just one potential technique. There are others, from injecting water straight into wells to developing pits and basins designed specifically for infiltration. It’s a plumbing challenge on an unprecedented scale.

The act of putting water back into aquifers has a number of unglamorous names — enhanced aquifer recharge, water banking, artificial groundwater recharge, and aquifer storage and recovery, among others — with some nuanced differences between them. But they all mean roughly the same thing: increasing the amount of water that infiltrates into the ground and ultimately into aquifers.

This can have the overall effect of smoothing the high peaks and deep valleys of water supply in places dealing with extreme weather fluctuations. The idea is to capture the extra water that floods during periods of intense rainfall, and bank it for use during droughts. (While aquifers can also be recharged using any old freshwater, water rights are so complicated in the West that floodwater often represents “the only surface water that’s not spoken for,” Thomas Harter, a groundwater hydrology professor at U.C. Davis, told local television outlet KCRA.)

Recharge has the potential added benefit of protecting groundwater from saltwater intrusion. As water is pumped from a coastal aquifer, water from the ocean can seep in to fill the empty space, potentially poisoning the well for future use for agriculture or drinking water. It’s a risk that will only get bigger as the climate warms and sea levels rise.

Get the best of Heatmap in your inbox every day:

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, aquifer recharge is most often used in places where groundwater demand is high and increasing even as supply remains limited. These tend to be places with lots of people and lots of farms; the San Joaquin Valley, which is the focus of California’s current plan, checks all of those boxes. Aquifers are the source of nearly 40% of water used by farms and cities in California, per the Public Policy Institute of California, and more in dry years. And, until 2023, most recent years have been dry.

In response to this year’s sudden reversal of California’s water fortunes, the state’s Water Board — which regulates water rights — allowed local contractors of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to move up to 600,000 acre-feet of water, or well over a trillion gallons, to places that normally would be off-limits this time of year. Those contractors, who are largely farmers and other major landowners, have until July 30 to take advantage.

“California is essentially the pilot project for how we want to do this in the future,” said Erik Ekdahl, deputy director for the Water Board’s water rights division. It won’t be until the end of the year that the state will know exactly how much water was successfully banked, but Ekdahl said anecdotally that some contractors have already taken steps to put the spare water underground.

This comes as California’s enormous snowpack begins to melt: a potential boon for the aquifers that could also mean problematic and dangerous floods for the communities downstream of the runoff.

How does enhanced aquifer recharge actually happen? It’s not as if the vast underground stretches of rock and sediment have faucets or even obvious holes leading to their watery depths. People aiming to reverse the centuries-long trend of drawing up water without actively replacing it have a range of artificial recharge options, which either speed along the natural seepage process or direct water straight to the aquifer below.

In the former cases, one option is to allow water to flood fields left fallow, a process known as “surface spreading,” as is beginning to happen in the San Joaquin Valley.

Water can also be directed to dedicated recharge basins and canals. In both cases, excess water is absorbed by fast-draining soil, which encourages it to pass below ground. Aside from the technical challenge of redirecting water from typical flood patterns, these approaches tend to be low-tech.

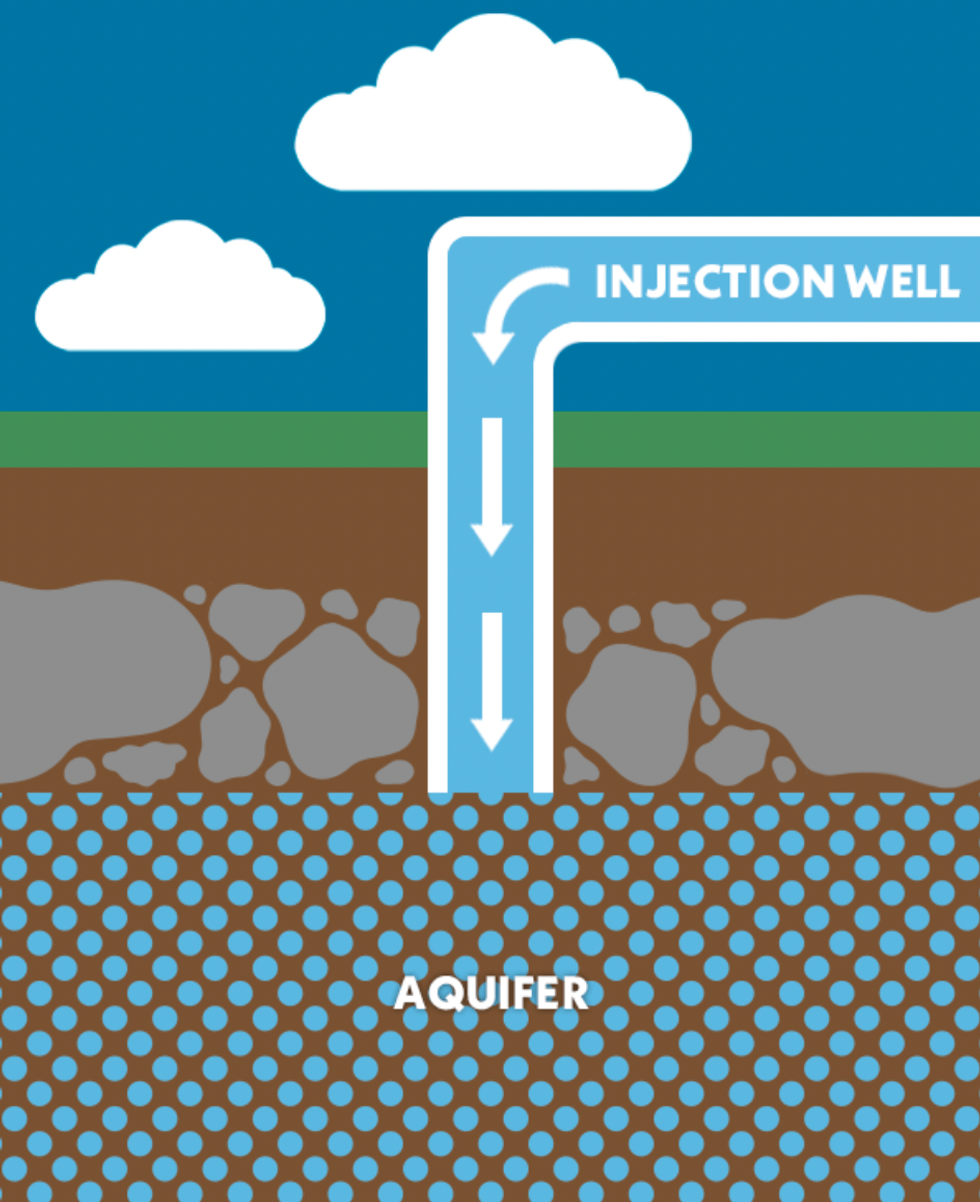

But in cases of aquifer depletion where those approaches are impractical — such as when the aquifer is under impermeable rock — injection wells represent a direct connection to the groundwater. These are either deep pits that drain into sedimentary layers above an underground drinking water source (like a traditional well functioning in reverse), or else webs of tubes and casing that blast water straight into the source.

Cities are also experimenting with aquifer recharge on a smaller scale. For urban stormwater, the EPA promotes certain “green infrastructure” approaches that mold the built environment to mimic natural hydrology. For instance, shallow channels lined with vegetation, known as bioswales, redirect stormwater while encouraging it to seep through the ground. Permeable pavement — in use in several Northeastern states — works much the same way. Meanwhile, rain gardens designed to prevent flooding have the added benefit of replenishing groundwater.

Determining when and where to use different approaches to aquifer recharge, though, can be unclear. We are still a long way from widespread or coordinated adoption of these techniques, but researchers are working on weighing their costs and benefits.

Supported by a $2 million EPA grant, Kiparsky is part of a U.C. Berkeley team looking at how to make California-esque recharge work on a national scale. , including by developing a cost-benefit tool for water managers. Some of the geochemical and physical considerations are relatively simple to measure: Is the soil in question porous? Are there gravel-filled “paleo valleys” that could allow water to rapidly seep to the aquifers below, as one 2022 study found?

More complicated, potentially immeasurable, but no less important are the legal and regulatory considerations around water rights. It is, as Kiparsky put it, one of the quintessential modern examples of the tragedy of the commons. Whether the government will be able to entice individuals to use their own little corner of Earth to fill an aquifer for the benefit of the many is an open question.

But Kiparsky is fairly optimistic that recharge will take hold in years where there is water to spare, as the West recognizes that future drought must be prepared for, especially when it’s raining.

“Is recharge going to become a bigger part of water management? I would say absolutely,” he said. “I’m not usually in the game of making predictions, but I would predict the answer is yes. When we can figure out how to do it.”

Get the best of Heatmap in your inbox every day:

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Current conditions: Temperatures as low as 30 degrees Fahrenheit below average are expected to persist for at least another week throughout the Northeast, including in New York City • Midsummer heat is driving temperatures up near 100 degrees in Paraguay • Antarctica is facing intense katabatic winds that pull cold air from high altitudes to lower ones.

The United States has, once again, exited the Paris Agreement, the first global carbon-cutting pact to include the world’s two top emitters. President Donald Trump initiated the withdrawal on his first day back in office last year — unlike the last time Trump quit the Paris accords, after a prolonged will-he-won’t-he game in 2017. That process took three years to complete, allowing newly installed President Joe Biden to rejoin in 2021 after just a brief lapse. This time, the process took only a year to wrap up, meaning the U.S. will remain outside the pact for years at least. “Trump is making unilateral decisions to remove the United States from any meaningful global climate action,” Katie Harris, the vice president of federal affairs at the union-affiliated BlueGreen Alliance, said in a statement. “His personal vendetta against clean energy and climate action will hurt workers and our environment.” Now, as Heatmap’s Katie Brigham wrote last year, at “all Paris-related meetings (which comprise much of the conference), the U.S. would have to attend as an ‘observer’ with no decision-making power, the same category as lobbyists.”

America has not yet completed its withdrawal from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the overarching group through which the Paris Agreement was negotiated, which Trump initiated this month. That won’t be final until next year. That Trump is even planning to quit the body shows how much more aggressive the administration’s approach to climate policy is this time around. Trump remained within the UNFCCC during his first term, preferring to stay engaged in negotiations even after quitting the Paris Agreement.

Just weeks after a federal judge struck down the Trump administration’s stop work order on the Revolution Wind project off Rhode Island’s shores, another federal judge has overturned the order halting construction on the Vineyard Wind project off Massachusetts. That, as Heatmap’s Emily Pontecorvo wrote last night, “makes four offshore wind farms that have now won preliminary injunctions against Trump’s freeze on the industry.” Besides Revolution Wind, Dominion Energy’s Coastal Virginia offshore wind project and Equinor’s Empire Wind plant off Long Island have each prevailed in their challenges to the administration’s blanket order to abandon construction on dubious national security grounds.

Meanwhile, the White House is potentially starving another major infrastructure project of funding. The Gateway rail project to build a new tunnel under the Hudson River between New Jersey and New York City could run out of money and halt construction by the end of next week, the project manager warned Tuesday. Washington had promised billions to get the project done, but the money stopped flowing in October during the government shutdown. Officials at the Department of Transportation said the funding would remain suspended until, as The New York Times reported, the project’s contracts could be reviewed for compliance with new rules about businesses owned by women and minorities.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

A new transmission line connecting New England’s power-starved and gas-addicted grid to Quebec’s carbon-free hydroelectric system just came online this month. But electricity abruptly stopped flowing onto the New England Clean Energy Connect as the Canadian province’s state-owned utility, Hydro-Quebec, withheld power to meet skyrocketing demand at home amid the Arctic chill. Power plant owners in New England and New York, where Hydro-Quebec is building another line down the Hudson River to connect to New York City, complained that deals with the utility focused on maintaining supplies during the summer, when air conditioning traditionally surges power to peak demand. Hydro-Quebec restored power to the line on Monday.

The storm represented a force majeure event. If it hadn’t, the utility would have needed to pay penalties. But the incident is sure to fuel more criticism from power plant owners, most of which are fossil fueled, who oppose increased competition from the Quebecois. “I hate to say it, but a lot of the issues and concerns that we have been talking about for years have played out this weekend,” Dan Dolan — who leads the New England Power Generators Association, a trade group representing power plant owners — told E&E News. “This is a very expensive contract for a product that predominantly comes in non-stressed periods in the winter,” he said.

Europe has signed what the European Commission president Urusula von der Leyen called “the mother of all deals” with India, “a free trade zone of 2 billion people.” As part of the deal, the world’s second-largest market and the most populous nation plan to ramp up exports of steel, plastics, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals. But don’t expect Brussels to give New Delhi a break on its growing share of the global emissions. The EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism — the first major tariff in the world based on the carbon intensity of imports — just took effect this month, and will remain intact for Indian goods, Reuters reported.

The Department of the Interior has ordered staff at the National Park Service to remove or edit signs and other informational materials in at least 17 parks out West to scrub mentions of climate change or hardship inflicted by settlers on Native Americans. The effort comes as part of what The Washington Post called a renewed push to implement Trump’s executive order on “restoring truth and sanity to American history.” Park staff have interpreted those orders, the newspaper reported, to mean eliminating any reference to historic racism, sexism, LGBTQ rights, and climate change. Just last week, officials removed an exhibit at Independence National Historical Park on George Washington’s ownership of slaves.

Tesla is going trucking. The electric automaker inked a deal Tuesday with Pilot Travel Centers, the nation’s largest operator of highway pit stops, to install Tesla’s Semi Chargers for heavy-duty electric vehicle charging. The stations are set to be built at select Pilot locations along Interstate 5, Interstate 10, and several other major corridors where heavy-duty charging is highest. The first sites are scheduled to open this summer.

Rob talks with McMaster University engineering professor Greig Mordue, then checks in with Heatmap contributor Andrew Moseman on the EVs to watch out for.

It’s been a huge few weeks for the electric vehicle industry — at least in North America.

After a major trade deal, Canada is set to import tens of thousands of new electric vehicles from China every year, and it could soon invite a Chinese automaker to build a domestic factory. General Motors has also already killed the Chevrolet Bolt, one of the most anticipated EV releases of 2026.

How big a deal is the China-Canada EV trade deal, really? Will we see BYD and Xiaomi cars in Toronto and Vancouver (and Detroit and Seattle) any time soon — or is the trade deal better for Western brands like Volkswagen or Tesla which have Chinese factories but a Canadian presence? On this week’s Shift Key, Rob talks to Greig Mordue, a former Toyota executive who is now an engineering professor at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, about how the deal could shake out. Then he chats with Heatmap contributor Andrew Moseman about why the Bolt died — and the most exciting EVs we could see in 2026 anyway.

Shift Key is hosted by Robinson Meyer, the founding executive editor of Heatmap, and Jesse Jenkins, a professor of energy systems engineering at Princeton University. Jesse is off this week.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Here is an excerpt from our conversation:

Robinson Meyer: Over the weekend there was a new tariff threat from President Trump — he seems to like to do this on Saturday when there are no futures markets open — a new tariff threat on Canada. It is kind of interesting because he initially said that he thought if Canada could make a deal with China, they should, and he thought that was good. Then over the weekend, he said that it was actually bad that Canada had made some free trade, quote-unquote, deal with China.

Do you think that these tariff threats will affect any Carney actions going forward? Is this already priced in, slash is this exactly why Carney has reached out to China in the first place?

Greig Mordue: I think it all comes under the headline of “deep sigh,” and we’ll see where this goes. But for the first 12 months of the U.S. administration, and the threat of tariffs, and the pullback, and the new threat, and this going forward, the public policy or industrial policy response from the government of Canada and the province of Ontario, where automobiles are built in this country, was to tread lightly. And tread lightly, generally means do nothing, and by doing nothing stop the challenges.

And so doing nothing led to Stellantis shutting down an assembly plant in Brampton, Ontario; General Motors shutting an assembly plant in Ingersoll, Ontario; General Motors reducing a three-shift operation in Oshawa, Ontario to two shifts; and Ford ragging the puck — Canadian term — on the launch of a new product in their Oakville, Ontario plant. So doing nothing didn’t really help Canada from a public policy perspective.

So they’re moving forward on two fronts: One is the resetting of relationships with China and the hope of some production from Chinese manufacturers. And two, the promise of automotive industrial policy in February, or at some point this spring. So we’ll see where that goes — and that may cause some more restless nights from the U.S. administration. We’ll see.

Mentioned:

Canada’s new "strategic partnership” with China

The Chevy Bolt Is Already Dead. Again.

The EVs Everyone Will Be Talking About in 2026

This episode of Shift Key is sponsored by …

Heatmap Pro brings all of our research, reporting, and insights down to the local level. The software platform tracks all local opposition to clean energy and data centers, forecasts community sentiment, and guides data-driven engagement campaigns. Book a demo today to see the premier intelligence platform for project permitting and community engagement.

Music for Shift Key is by Adam Kromelow.

A federal judge in Massachusetts ruled that construction on Vineyard Wind could proceed.

The Vineyard Wind offshore wind project can continue construction while the company’s lawsuit challenging the Trump administration’s stop work order proceeds, judge Brian E. Murphy for the District of Massachusetts ruled on Tuesday.

That makes four offshore wind farms that have now won preliminary injunctions against Trump’s freeze on the industry. Dominion Energy’s Coastal Virginia offshore wind project, Orsted’s Revolution Wind off the coast of New England, and Equinor’s Empire Wind near Long Island, New York, have all been allowed to proceed with construction while their individual legal challenges to the stop work order play out.

The Department of the Interior attempted to pause all offshore wind construction in December, citing unspecified “national security risks identified by the Department of War.” The risks are apparently detailed in a classified report, and have been shared neither with the public nor with the offshore wind companies.

Vineyard Wind, a joint development between Avangrid Renewables and Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners, has been under construction since 2021, and is already 95% built. More than that, it’s sending power to Massachusetts customers, and will produce enough electricity to power up to 400,000 homes once it’s complete.

In court filings, the developer argued it was urgent the stop work order be lifted, as it would lose access to a key construction boat required to complete the project on March 31. The company is in the process of replacing defective blades on its last handful of turbines — a defect that was discovered after one of the blades broke in 2024, scattering shards of fiberglass into the ocean. Leaving those turbine towers standing without being able to install new blades created a safety hazard, the company said.

“If construction is not completed by that date, the partially completed wind turbines will be left in an unsafe condition and Vineyard Wind will incur a series of financial consequences that it likely could not survive,” the company wrote. The Trump administration submitted a reply denying there was any risk.

The only remaining wind farm still affected by the December pause on construction is Sunrise Wind, a 924-megawatt project being developed by Orsted and set to deliver power to New York State. A hearing for an injunction on that order is scheduled for February 2.