You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

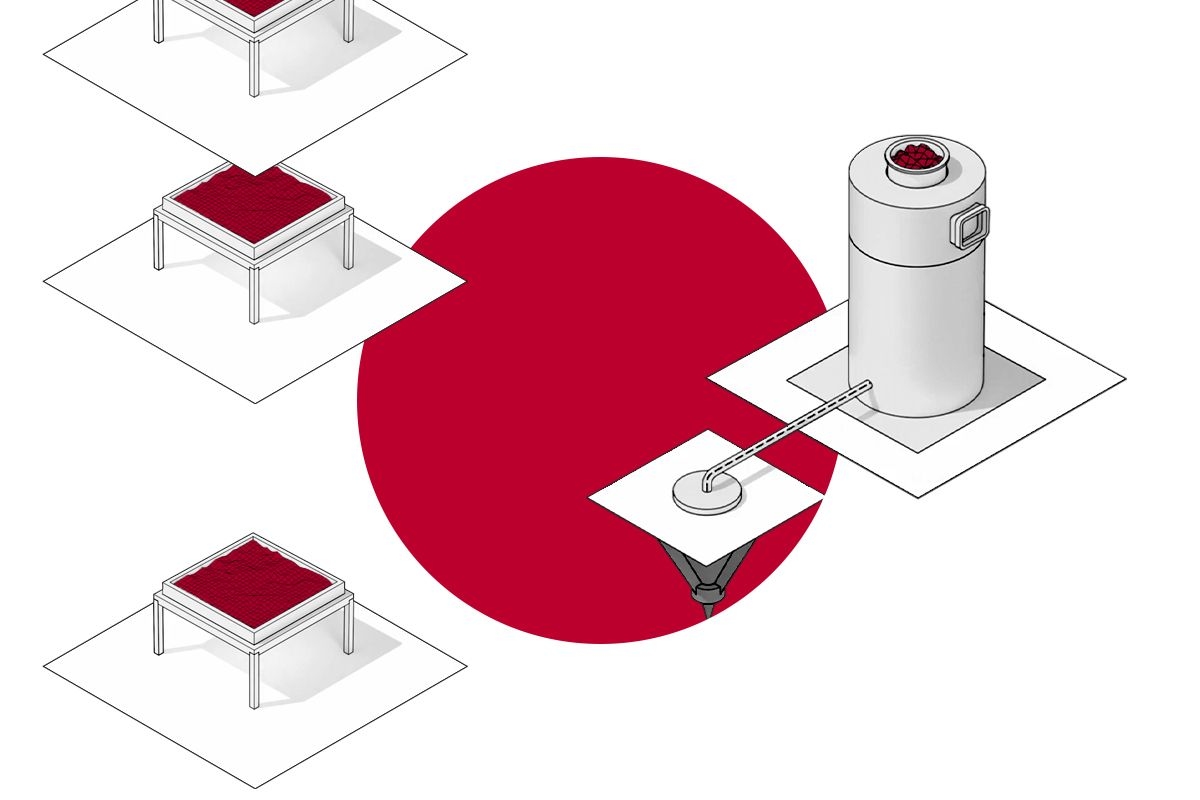

With new corporate emissions restrictions looming, Japanese investors are betting on carbon removal.

It’s not a great time to be a direct air capture company in the U.S. During a year when the federal government stepped away from its climate commitments and cut incentives for climate tech and clean energy, investors largely backed away from capital-intensive projects with uncertain economics. And if there were ever an expensive technology without a clear path to profitability, it’s DAC.

But as the U.S. retrenches, Japanese corporations are leaning in. Heirloom’s $150 million Series B round late last year featured backing from Japan Airlines, as well as major Japanese conglomerates Mitsubishi Corporation and Mitsui & Co. Then this month, the startup received an additional infusion of cash from the Development Bank of Japan and the engineering company Chiyoda Corporation. Just days later, DAC project developer Deep Sky announced a strategic partnership with the large financial institution Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation to help build out the country’s DAC market.

Experts told me these investments probably won’t lead to much large-scale DAC deployment within Japan, where the geology is poorly suited to carbon sequestration. Many of these corporations likely don’t even plan to purchase DAC-based carbon offsets anytime soon, as they haven’t made the type of bold clean energy commitments seen among U.S. tech giants, and cheaper forestry offsets still dominate the local market.

Rather, contrary to current sentiment in the U.S., many simply view it as a fantastic business opportunity. “This is actually a great investment opportunity for Japanese companies now that the U.S. companies are out,” Yuki Sekiguchi, founder of Startup Navigator for Climate Tech and the leader of a group for the Japanese clean tech community, told me. “They get to work with really high caliber startups. And now everybody’s going to Japan to raise money and have a partnership, so they have a lot to choose from.”

Chris Takigawa, a director at the Tokyo-based venture firm Global Brain, agreed. Previously he worked at Mitsubishi, where he pioneered research on CO2 removal technologies and led the company’s investment in Heirloom. “Ultimately, if there’s going to be a big project, we want to be part of that, to earn equity from that business,” he told me of Mitsubishi’s interest in DAC. “We own large stakes in mining assets or heavy industrial assets. We see this as the same thing.”

Takigawa said that he sees plenty of opportunities for the country to leverage its engineering and manufacturing expertise to play a leading role in the DAC industry’s value chain. Many Japanese companies have already gotten a jump.

To name just a few, NGK Insulators is researching ceramic materials for carbon capture, and semiconductor materials company Tokyo Ohka Kogyo is partnering with the Japanese DAC startup Carbon Xtract to develop and manufacture carbon capture membranes. The large conglomerate Sojitz is working with academic and energy partners to turn Carbon Xtract’s tech into a small-scale “direct air capture and utilization" system for buildings. And the industrial giant Kawasaki Heavy Industries has built a large DAC pilot plant in the port city of Kobe, as the company looks to store captured CO2 in concrete.

During his time at Mitsubishi, as he worked to establish the precursor to what would become the Japan CDR Coalition, Takigawa told me he reached out to “all the companies that I could think about that might be related to DAC.” Most of them, he found, were already either doing research or investing in the space.

Japan has clear climate targets — reach net-zero by 2050, with a 60% reduction in emissions by 2035, and a 73% reduction by 2040, compared to 2013 levels. It’s not among the most ambitious countries, nor is it among the least. But experts emphasize that its path is stable and linear.

“In Japan, policy is a little more top down,” Sekiguchi told me. Japan’s business landscape is dominated by large conglomerates and trading companies, which Sekigushi told me are “basically tasked by the government” to decarbonize. “And then you have to follow.”

Unlike in the U.S., climate change and decarbonization are not very politically charged issues in Japan. But at the same time, there’s little perceived need for engagement. A recent Ipsos poll showed that among the 32 countries surveyed, Japanese citizens expressed the least urgency to act on climate change. And yet, there’s broad agreement there that climate change is a big problem, as 81% of Japanese people surveyed said they’re worried about the impacts already being felt in the country.

The idea that large corporations are being instructed to lower their emissions over a decades-long timeframe is thus not a major point of contention. The same holds for Japan’s now-voluntary emissions trading scheme, called the GX-ETS, that was launched in 2023. This coming fiscal year, compliance will become mandatory, with large polluters receiving annual emissions allowances that they can trade if they’re above or below the cap.

International credits generated from DAC and other forms of carbon removal, such as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage, are accepted forms of emissions offsets during the voluntary phase, making Japan the first country to include engineered credits in its national trading scheme. But to the dismay of the country’s emergent carbon removal sector, it now appears that they won’t be included in the mandatory ETS, at least initially. While a statement from the Chairman and CEO of Japan’s Institute of Energy Economics says that “carbon removal will be recognized in the future as credits,” it’s unclear when that will be.

Sekiguchi told me this flip-flop served as a wake-up call, highlighting the need for greater organizing efforts around carbon removal in Japan.

“Now those big trading houses realize they need an actual lobbying entity. So they created the Japan CDR Coalition this summer,” she explained. Launched by Mitsubishi, the coalition’s plans include “new research and analysis on CDR, policy proposals, and training programs,” according to a press release. The group’s first meeting was this September, but when I reached out to learn more about their efforts, a representative told me the coalition had “not yet reached a stage where we can effectively share details or outcomes with media outlets.”

Sekiguchi did tell me that the group has quickly gained momentum, growing from just a handful of founding companies to a membership of around 70, including representatives from most major sectors such as shipping, chemicals, electronics, and heavy industry.

Many of these companies — especially those in difficult to decarbonize sectors — might be planning for a future in which durable engineered carbon offsets do play a critical role in complying with the country’s increasingly stringent ETS requirements. After all, Japan is small, mountainous, densely populated, and lacks the space for vast deployments of solar and wind resources, leaving it largely dependent on imported natural gas for its energy needs. “We’ll always be using fossil fuels,” Takigawa told me, “So in order to offset the emissions, the only way is to buy carbon removals.”

And while the offset market is currently dominated by inexpensive nature-based solutions, “you have to have an expectation that the price is going to go up,” Sekiguchi told me. The project developer Deep Sky is certainly betting on that. As the company’s CEO Alex Petre told me, “Specifically in Japan, due to the very strong culture of engineering and manufacturing, there is a really deep recognition that engineered credits are actually a solution that is not only exciting, but also one where there’s a lot of opportunity to optimize and to build and to deploy.”

As it stands now though, the rest of the world may expect a little too much of Japan’s nascent DAC industry, experts told me.

Take the DeCarbon Tokyo conference, which was held at the beginning of December. Petre, Sekiguchi, and Takigawa all attended. Petre’s takeaway? “Deep Sky is not the only company that has figured out that Japan is really interested in decarbonization,” she put it wryly. DAC companies Climeworks and AirMyne were also present, along with a wide range of other international carbon removal startups such as Charm Industrial, Captura, and Lithos Carbon.

Overall, Sekiguchi — who attended the conference in her role as a senior advisor to the Bay Area-based AirMyne — estimated that about 80% of participants were international companies or stakeholders looking for Japanese investment, whereas “it should be the other way around” for a conference held in Tokyo.

“I think there’s big potential, Japan can be a really big player,” she told me. But perhaps Americans and Europeans are currently a little overzealous when it comes to courting Japanese investors and pinning their expectations on the country’s developing decarbonization framework. “There’s so much hope from the international side. But in Japan it’s still like, okay, we are learning, and we are going steadily but kind of slowly. So don’t overwhelm us.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

On the real copper gap, Illinois’ atomic mojo, and offshore headwinds

Current conditions: The deadliest avalanche in modern California history killed at least eight skiers near Lake Tahoe • Strong winds are raising the wildfire risk across vast swaths of the northern Plains, from Montana to the Dakotas, and the Southwest, especially New Mexico, Texas, and Oklahoma • Nairobi is bracing for days more of rain as the Kenyan capital battles severe flooding.

Last week, the Environmental Protection Agency repealed the “endangerment finding” that undergirds all federal greenhouse gas regulations, effectively eliminating the justification for curbs on carbon dioxide from tailpipes or smokestacks. That was great news for the nation’s shrinking fleet of coal-fired power plants. Now there’s even more help on the way from the Trump administration. The agency plans to curb rules on how much hazard pollutants, including mercury, coal plants are allowed to emit, The New York Times reported Wednesday, citing leaked internal documents. Senior EPA officials are reportedly expected to announce the regulatory change during a trip to Louisville, Kentucky on Friday. While coal plant owners will no doubt welcome less restrictive regulations, the effort may not do much to keep some of the nation’s dirtiest stations running. Despite the Trump administration’s orders to keep coal generators open past retirement, as Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote in November, the plants keep breaking down.

At the same time, the blowback to the so-called climate killshot the EPA took by rescinding the endangerment finding has just begun. Environmental groups just filed a lawsuit challenging the agency’s interpretation of the Clean Air Act to cover only the effects of regional pollution, not global emissions, according to Landmark, a newsletter tracking climate litigation.

Copper prices — as readers of this newsletter are surely well aware — are booming as demand for the metal needed for virtually every electrical application skyrockets. Just last month, Amazon inked a deal with Rio Tinto to buy America’s first new copper output for its data center buildout. But new research from a leading mineral supply chain analyst suggests the U.S. can meet 145% of its annual demand using raw copper from overseas and domestic mines and from scrap. By contrast, China — the world’s largest consumer — can source just 40% of its copper that way. What the U.S. lacks, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, is the downstream processing capacity to turn raw copper into the copper cathode manufacturers need. “The U.S. is producing more copper than it uses, and is far more self-reliant than China in terms of raw materials,” Benchmark analyst Albert Mackenzie told the Financial Times. The research calls into question the Trump administration’s mineral policy, which includes stockpiling copper from jointly-owned ventures in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and domestically. “Stockpiling metal ores doesn’t help if you don’t have midstream processing,” Stephen Empedocles, chief executive of US lobbying firm Clark Street Associates, told the newspaper.

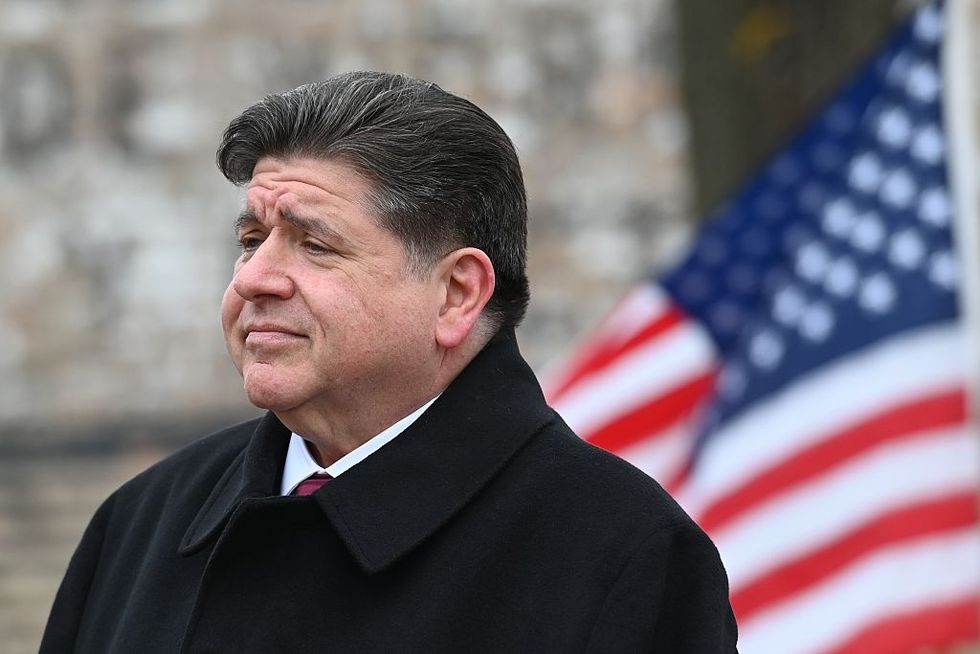

Illinois generates more of its power from nuclear energy than any other state. Yet for years the state has banned construction of new reactors. Governor JB Pritzker, a Democrat, partially lifted the prohibition in 2023, allowing for development of as-yet-nonexistent small modular reactors. With excitement about deploying large reactors with time-tested designs now building, Pritzker last month signed legislation fully repealing the ban. In his state of the state address on Wednesday, the governor listed the expansion of atomic energy among his administration’s top priorities. “Illinois is already No. 1 in clean nuclear energy production,” he said. “That is a leadership mantle that we must hold onto.” Shortly afterward, he issued an executive order directing state agencies to help speed up siting and construction of new reactors. Asked what he thought of the governor’s move, Emmet Penney, a native Chicagoan and nuclear expert at the right-leaning Foundation for American Innovation, told me the state’s nuclear lead is “an advantage that Pritzker wisely wants to maintain.” He pointed out that the policy change seems to be copying New York Governor Kathy Hochul’s playbook. “The governor’s nuclear leadership in the Land of Lincoln — first repealing the moratorium and now this Hochul-inspired executive order — signal that the nuclear renaissance is a new bipartisan commitment.”

The U.S. is even taking an interest in building nuclear reactors in the nation that, until 1946, was the nascent American empire’s largest overseas territory. The Philippines built an American-made nuclear reactor in the 1980s, but abandoned the single-reactor project on the Bataan peninsula after the Chernobyl accident and the fall of the Ferdinand Marcos dictatorship that considered the plant a key state project. For years now, there’s been a growing push in Manila to meet the country’s soaring electricity needs by restarting work on the plant or building new reactors. But Washington has largely ignored those efforts, even as the Russians, Canadians, and Koreans eyed taking on the project. Now the Trump administration is lending its hand for deploying small modular reactors. The U.S. Trade and Development Agency just announced funding to help the utility MGEN conduct a technical review of U.S. SMR designs, NucNet reported Wednesday.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

Despite the American government’s crusade against the sector, Europe is going all in on offshore wind. For a glimpse of what an industry not thrust into legal turmoil by the federal government looks like, consider that just on Wednesday the homepage of the trade publication OffshoreWIND.biz featured stories about major advancements on at least three projects totaling nearly 5 gigawatts:

That’s not to say everything is — forgive me — breezy for the industry. Germany currently gives renewables priority when connecting to the grid, but a new draft law would give grid operators more discretion when it comes to offshore wind, according to a leaked document seen by Windpower Monthly.

American clean energy manufacturing is in retreat as the Trump administration’s attacks on consumer incentives have forced companies to reorient their strategies. But there is at least one company setting up its factories in the U.S. The sodium-ion battery startup Syntropic Power announced plans to build 2 gigawatts of storage projects in 2026. While the North Carolina-based company “does not reveal where it manufactures its battery systems,” Solar Power World reported, it “does say” it’s establishing manufacturing capacity in the U.S. “We’re making this move now because the U.S. market needs storage that can be deployed with confidence, supported by certification, insurance acceptance, and a secure domestic supply chain,” said Phillip Martin, Syntropic’s chief executive.

For years now, U.S. manufacturers have touted sodium-ion batteries as the next big thing, given that the minerals needed to store energy are more abundant and don’t afford China the same supply-chain advantage that lithium-ion packs do. But as my colleague Katie Brigham covered last April, it’s been difficult building a business around dethroning lithium. New entrants are trying proprietary chemistries to avoid the mistakes other companies made, as Katie wrote in October when the startup Alsym launched a new stationary battery product.

Last spring, Heron Power, the next-generation transformer manufacturer led by a former Tesla executive, raised $38 million in a Series A round. Weeks later, Spain’s entire grid collapsed from voltage fluctuations spurred by a shortage of thermal power and not enough inverters to handle the country’s vast output of solar power — the exact kind of problem Heron Power’s equipment is meant to solve. That real-life evidence, coupled with the general boom in electrical equipment, has clearly helped the sales pitch. On Wednesday, the company closed a $140 million Series B round co-led by the venture giants Andreessen Horowitz and Breakthrough Energy Ventures. “We need new, more capable solutions to keep pace with accelerating energy demand and the rapid growth of gigascale compute,” Drew Baglino, Heron’s founder and chief executive, said in a statement. “Too much of today’s electrical infrastructure is passive, clunky equipment designed decades ago. At Heron we are manifesting an alternative future, where modern power electronics enable projects to come online faster, the grid to operate more reliably, and scale affordably.”

A senior scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy on what Trump has lost by dismantling Biden’s energy resilience strategy.

A fossil fuel superpower cannot sustain deep emissions reductions if doing so drives up costs for vulnerable consumers, undercuts strategic domestic industries, or threatens the survival of communities that depend on fossil fuel production. That makes America’s climate problem an economic problem.

Or at least that was the theory behind Biden-era climate policy. The agenda embedded in major legislation — including the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act — combined direct emissions-reduction tools like clean energy tax credits with a broader set of policies aimed at reshaping the U.S. economy to support long-term decarbonization. At a minimum, this mix of emissions-reducing and transformation-inducing policies promised a valuable test of political economy: whether sustained investments in both clean energy industries and in the most vulnerable households and communities could help build the economic and institutional foundations for a faster and less disruptive energy transition.

Sweeping policy reversals have cut these efforts short. Abandoning the strategy makes the U.S. economy less resilient to the decline of fossil fuels. It also risks sowing distrust among communities and firms that were poised to benefit, complicating future efforts to recommit to the economic policies needed to sustain an energy transition.

This agenda rested on the idea that sustaining decarbonization would require structural changes across the economy, not just cleaner sources of energy. First, in a country that derives substantial economic and geopolitical power from carbon-intensive industries, a durable energy transition would require the United States to become a clean energy superpower in its own right. Only then could the domestic economy plausibly gain, rather than lose, from a shift away from fossil fuels.

Second, with millions of households struggling to afford basic energy services and fossil fuels often providing relatively cheap energy, climate policy would need to ensure that clean energy deployment reduces household energy burdens rather than exacerbates them.

Third, policies would need to strengthen the economic resilience of communities that rely heavily on fossil fuel industries so the energy transition does not translate into shrinking tax bases, school closures, and lost economic opportunity in places that have powered the country for generations.

This strategy to reshape the economy for the energy transition has largely been dismantled under President Trump.

My recent research examines federal support for fossil fuel-reliant communities, assessing President Biden’s stated goal of “revitalizing the economies of coal, oil, gas, and power plant communities.” Federal spending data provides little evidence that these at-risk communities have been effectively targeted. One reason is timing: While legislation authorized unprecedented support, actual disbursements lagged far behind those commitments.

Many of the key policies — including $4 billion in manufacturing tax credits reserved for communities affected by coal closures — took years to move from statutory language to implementation guidance and final project selection. As a result, aside from certain pandemic-era programs, fossil fuel-reliant communities had received limited support by the time Trump took office last year.

Since then, the Trump administration and Congress have canceled projects intended to benefit fossil fuel-reliant regions, including carbon capture and clean hydrogen demonstrations, and discontinued programs designed to help communities access and implement federal funding.

Other elements of the strategy to reduce the country’s vulnerability to fossil fuel decline have fared even worse under the Trump administration. Programs intended to help households access and afford clean energy — most notably the $27 billion Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund — were effectively canceled last year, including attempts to claw back previously awarded funds. More broadly, the rollback of IRA programs with an explicit equity or justice focus leaves lower-income households more exposed to the economic disruptions that can accompany an energy transition.

By contrast, subsidies and grant programs aimed at strengthening the country’s energy manufacturing base have largely survived, including tax credits supporting domestic production of batteries, solar components, and other key technologies. Even so, the investment environment has weakened. Automakers have scaled back planned U.S. battery manufacturing expansions. Clean Investment Monitor data shows annual clean energy manufacturing investments on pace to decline in 2025, after rising sharply from 2022 to 2024. Whatever one believed about the potential to build globally competitive domestic supply chains for the technologies that will power clean energy systems, those prospects have dimmed amid slowing investment and the Trump administration’s prioritization of fossil fuels.

Perhaps these outcomes were unavoidable. Building a strong domestic solar industry was always uncertain, and place-based economic development programs have a mixed track record even under favorable conditions. Still, the Biden-era approach reflected a coherent theory of climate politics that warranted a real-world test.

Over the past year, debates in climate policy circles have centered on whether clean energy progress can continue under less supportive federal policies, with plausible cases made on both sides. The fate of Biden’s broader economic strategy to sustain the energy transition, however, is less ambiguous. The underlying dependence of the United States on fossil fuels across industries, households, and many local communities remains largely unchanged.

New data from the Clean Investment Monitor shows the first year-over-year quarterly decline since the project began.

Investment in the clean economy is flagging — and the electric vehicle supply chain is taking the biggest hit.

The Clean Investment Monitor, a project by the Rhodium Group and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research that tracks spending on the energy transition, found that total investment in clean technology in the last three months of 2025 was $60 billion. That compares to $68 billion in the fourth quarter of 2024 and $79 billion in the third quarter of last year. While total clean investment in 2025 was $277 billion — the highest the group has ever recorded — the fourth quarter of 2025 was the first time since the Clean Investment Monitor began tracking that the numbers fell compared to the same quarter the year before.

“Since 2019, quarterly investment has surpassed the level observed in the same period of the previous year — even when quarter-on-quarter declines occurred,” the report says. “That trend ended in Q4 2025, when investment declined 11% from the level observed in Q4 2024.”

It starts downstream, with consumer purchases of clean energy technology once favored by federal tax policy: electric vehicles, heat pumps, and home electricity generation. Consumer purchases fell 36% from the third quarter to the fourth quarter, after the $7,500 federal EV credit expired on September 30.

With a consumer market for EVs being undercut, car companies responded by canceling projects and redirecting investment.

“There were a lot of big, multi-billion dollar cancellations coming from Ford specifically,” Harold Tavarez, a research analyst at Rhodium, told me. There’s been a lot of pivots from having fully electric vehicles to doing more hybrids, more internal combustion, and even extended range EVs.”

Ford alone took an almost $20 billion hit on its EV investments in 2025. The company suspended production of its all-electric F-150 Lightning late last year, despite its status as the best-selling electric pickup in the country for 2025, and announced a pivot into hybrids and extended-range EVs (which have gasoline-powered boosters onboard), including a revamped Lightning. It has also announced plans to convert some manufacturing facilities designed to produce EVs back into internal combustion plants, but it hasn’t abandoned electricity entirely. Other decommissioned EV factories will instead produce battery electric storage systems, and the company has announced a pivot to smaller, cheaper EVs.

Ford is far from alone in its EV-related pain, however. Rival Big Three automaker GM also booked $6 billion in losses for 2025, while Stellantis, the European parent company of the Chrysler, Dodge, and Jeep brands, will take as much as $26 billion in charges. EV sales fell some 46% in the fourth quarter of last year compared to the third quarter, and 36% compared to the fourth quarter of 2024, according to Cox Automotive.

Looking at the investment data holistically, the true dramatic decline was in forward-looking announcements, again heavily concentrated in the EV supply chain. The $3 billion in clean manufacturing announced in the fourth quarter of last year was an almost 50% drop from the previous quarter, “marking this quarter as the lowest period of announcements since Q4 2020,” the report says. Announcements were down about 25% for the year as a whole compared to 2024. Of the $29 billion of canceled projects Clean Investment Monitor tracked from 2018 through the end of last year, almost three quarters — some $23 billion — happened in 2025.

“Collectively, we estimate around 27,000 operational jobs in the manufacturing segment were affected by cancellations,” the report says, “two-thirds (68%) of which were tied to projects canceled in 2025.”

“One of the most frustrating parts of watching Trump wage war on all things clean energy is the apparent lack of understanding — or care — of how it impacts his stated goals,” Alex Jacquez, a former Biden economic policy official who is chief of policy and advocacy at the Groundwork Collective, told me. “The IRA built a real, competitive manufacturing base in the U.S. in a new sector for the first time in decades. Administration priorities are being hampered by blind opposition to anything Biden, IRA, or clean energy.”