You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

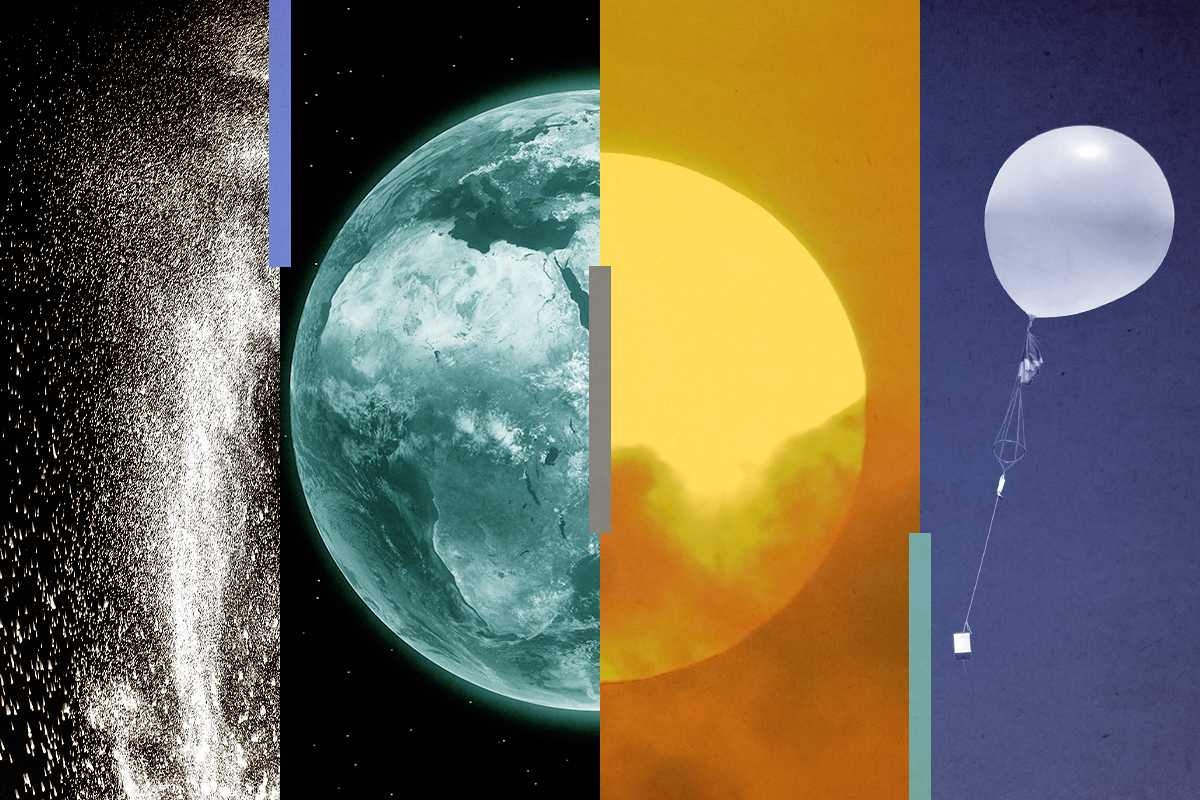

A U.S. firm led by former Israeli government physicists, Stardust seeks to patent its proprietary sunlight-scattering particle — but it won’t deploy its technology until global governments authorize such a move, its CEO says.

The era of the geoengineering startup has seemingly arrived.

Stardust Solutions, a company led by a team of Israeli physicists, announced on Friday that it has raised $60 million in venture capital to develop technological building blocks that it says will make solar geoengineering possible by the beginning of next decade.

It is betting that it can be the first to develop solar geoengineering technology, a hypothetical approach that uses aerosols to reflect sunlight away from Earth’s surface to balance out the effects of greenhouse gases. Yanai Yedvab, Stardust’s CEO, says that the company’s technology will be ready to deploy by the end of the decade.

The funding announcement represents a coming out of sorts for Stardust, which has been one of the biggest open secrets in the small world of solar geoengineering researchers. The company is — depending on how you look at it — either setting out a new way to research solar radiation management, or SRM, or violating a set of informal global norms that have built up to govern climate-intervention research over time.

Chief among these: While universities, nonprofits, and government labs have traditionally led SRM studies, Stardust is a for-profit company. It is seeking a patent for aspects of its geoengineering system, including protections for the reflective particles that it hopes governments will eventually disperse in the atmosphere.

The company has sought the advice of former United Nations diplomats, federal scientists, and Silicon Valley investors in its pursuit of geoengineering technology. Lowercarbon Capital, one of the most respected climate tech venture capital firms, led the funding round. Stardust previously raised a seed round of $15 million from Canadian and Israeli investors. It has not disclosed a valuation.

Yedvab assured me that once Stardust’s geoengineering system is ready to deploy, governments will decide whether and when to do so.

But even if it is successful, Stardust’s technology will not remove climate risk entirely. “There will still be extreme weather events. We’re not preventing them altogether,” Yedvab said. Rather, tinkering with the Earth’s atmosphere on a planetary scale could help preserve something like normal life — “like the life that all of us, you, us, our children have been experiencing over the last few decades.” The new round of funding, he says, will put that dream within reach.

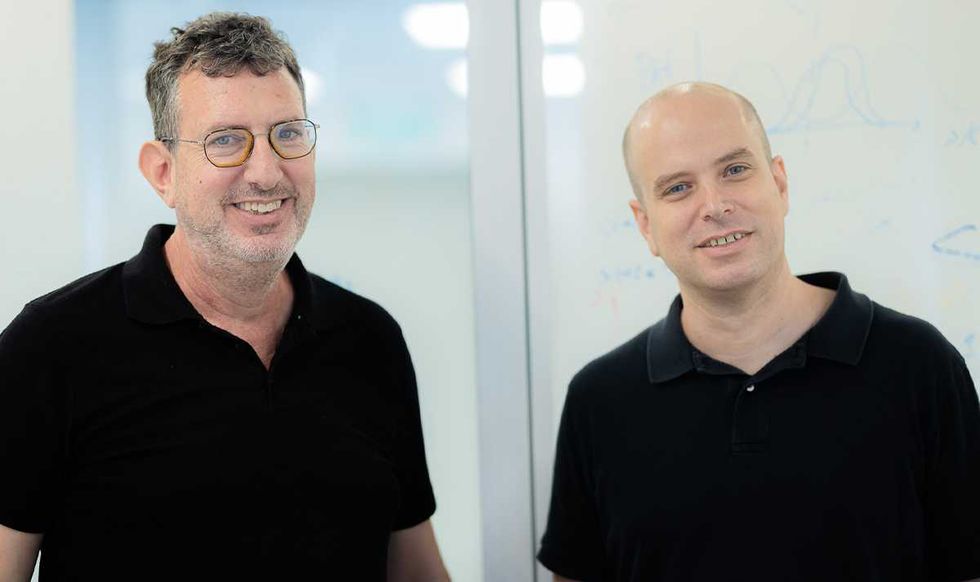

Yedvab, 54, has salt and pepper hair and a weary demeanor. When I met him earlier this month, he and his cofounder, Stardust Chief Product Officer Amyad Spector, had just flown into New York from Tel Aviv, before continuing on to Washington, D.C., that afternoon. Yedvab worked for many years at the center of the Israeli scientific and defense establishment. From 2011 to 2015, he was the deputy chief research scientist at the Israeli Atomic Energy Commission. He was also previously the head of the physics division at the highly classified Israeli nuclear research site in Negev, according to his LinkedIn.

Spector, 42, has also spent much of his career working for the Israeli government. He was a physics researcher at the Negev Nuclear Research Center before working on unspecified R&D projects for the government for nearly a decade, as well as on its Covid response. He left the government in December 2022.

Stardust’s story, in their telling, began in the wake of the pandemic, when they and their third cofounder — Eli Waxman, a particle physics professor at the Weizmann Institute of Science — became curious about climate change. “We started [with a] first principles approach,” Yedvab told me. What were countries’ plans to deal with warming? What did the data say? It was a heady moment in global climate politics: The United States and Europe had recently passed major climate spending laws, and clean energy companies were finally competing on cost with oil and gas companies.

Yet Yedvab was struck by how far away the world seemed to be from meeting any serious climate goal. “I think the thing that became very clear early on is that we’re definitely not winning here, right?” he told me. “These extreme weather events essentially destroy communities, drain ecosystems, and also may have major implications in terms of national security,” he said. “To continue doing what we’re doing over the next few decades and expecting materially different results will not get us where we want to be. And the implications can be quite horrific.”

Then they came across two documents that changed their thinking. The first was a 2021 report from the National Academies of Sciences in the United States, which argued that the federal government should establish “a transdisciplinary, solar geoengineering research program” — although it added that this must only be a “minor part” of the country’s overall climate studies and could not substitute for emissions reductions. Its authors seemed to treat solar geoengineering as a technology that could be developed in the near term, akin to artificial intelligence or self-driving cars.

They also found a much older article by the physicist Edward Teller — the same Teller who had battled with J. Robert Oppenheimer during the Manhattan Project. Teller had warned the oil industry about climate change as early as 1959, but in his final years he sought ways to avoid cutting fossil fuels at all. Writing in The Wall Street Journal weeks before the Kyoto Protocol meetings in 1997, an 89-year-old Teller argued that “contemporary technology offers considerably more realistic options for addressing any global warming effect” than politicians or activists were considering.

“One particularly attractive approach,” he wrote, was solar geoengineering. Blocking just 1% of sunlight could reduce temperatures while costing $100 million to $1 billion a year, he said, a fraction of the estimated societal cost of paring fossil fuels to their 1990 levels. A few years later, he wrote a longer report for the Energy Department arguing for the “active technical management” of the atmosphere rather than “administrative management” of fossil fuel consumption. He died in 2003.

The documents captivated the two scientists. What began to appeal to Yedvab and Spector was the economy of scale unlocked by the stratosphere — the way that just a few million tons of material could change the global climate. “It's very easy to understand why, if this works, the benefit could be enormous,” Yedvab said. “You can actually stop global warming. You can cool the planet and avoid a large part of the suffering. But then again, it was a very theoretical concept.” They incorporated Stardust in early 2023.

Economists had long anticipated the appeal of such an approach to climate management. Nearly two decades ago, the Columbia economist Scott Barrett observed that solar geoengineering’s economics are almost the exact opposite of climate change’s: While global warming is a “free rider” problem, where countries must collaborate to avoid burning cheap fossil fuels, solar geoengineering is a “free driver” problem, where one country could theoretically do it alone. Solar geonengineering’s risks lay in how easy it would be to do — and how hard it would be to govern.

Experts knew how you would do it, too: You would use sulfate aerosols — the tiny airborne chemicals formed when sulfur from volcanoes or fossil fuels reacts with water vapor, oxygen, and other substances in the air. In a now classic natural experiment Teller cited in his Journal op-ed, when Mount Pintabuo erupted in 1991 in the Philippines, it hurled a 20 million ton sulfur-dioxide cloud into the stratosphere, cooling the world by up to 1.3 degrees Fahrenheit before the sulfates rained out.

But to Yedvab, “sulfates look like a poor option,” he told me. Sulfates and sulfur oxides are nasty pollutants in their own right — they can cause asthma attacks, form acid rain, and may damage the ozone layer when in the stratosphere. For this reason, the International Maritime Organization adopted new rules restricting the amount of sulfur in cargo shipping fuels; these rules — in yet another natural experiment — seem to have accidentally accelerated global warming since 2020.

Yedvab and Spector anticipated another problem with sulfates: The atmosphere already contains tens of millions of tons of them. There is already so much sulfate in the sky from natural and industrial processes, they argue, that scientists would struggle to monitor whatever was released by geoengineers; Spector estimates that the smallest potential geoengineering experiment would require emitting 1 million tons of it. The chemical seemed to present an impossible trade-off to policymakers: How could a politician balance asthma attacks and acid rain against a cooler planet? “This is not something that decisionmakers can make a decision about,” Yedvab concluded.

Instead, the three founders tried starting at the end of the process, as they put it. What would an ideal geoengineering system look like? “Let’s say that we are successful in developing a system,” Yedvab said. “What will be the questions that people like you — that policymakers, the general public — will ask us?”

Any completed geoengineering system, they concluded, would need to meet a few constraints. It would need, first, a particle that could reflect a small amount of sunlight away from Earth while allowing infrared radiation from the planet’s surface to bounce back into space. That particle would need to be tested iteratively and manufactured easily in the millions of tons, which means it would also have to be low-cost.

“This needs to be a scalable or realistic particle that we know from the start how to produce at scale in the millions of tons, and at the relevant target price of a few dollars per kilo,” Yedvab said. “So not diamonds or something that we've done at the lab but have no idea how to scale it up,” Yedvab said.

It would need to be completely safe for people and the biosphere. Stardust hopes to run its particle through a safety process like the ones that the U.S. and EU subject food or other materials to, Yedvab said. “This needs to be as safe as, say, flour or some food ingredient,” Yedvab said. The particle would also need to be robust and inert in the stratosphere, and you would need some way to manage and identify it, perhaps even to track it, once it got there.

Second, the system would need some way to “loft” that particle into the stratosphere — some machine that could disperse the particle at altitude. Finally, it would need some way to make the particles observable and controllable, to make sure they are acting as intended. “For visibility, for control, for, I would say, geopolitical implications — you want to make sure you actually know where, how these particles move around, Yedvab said.

Stardust received $15 million in seed funding from the venture firm AWZ and Solar Edge, an Israeli energy company, in early 2024. Soon after, the founders got to work.

The world has come close to solving a global environmental crisis at least once before. In 1987, countries adopted the Montreal Protocol, which set out rules to eliminate and replace the chlorofluorocarbons that were destroying the stratospheric ozone hole. Nearly 40 years later, the ozone hole is showing signs of significant recovery. And more to the point, almost nobody talks about the ozone hole anymore, because someone else is dealing with it.

“I would say it was the biggest triumph of environmental diplomacy ever,” Yedvab said. “In three years, beginning to end, the U.S. government was able to secure the support of essentially all the major powers in solving a global problem.” The story is not quite that simple — the Reagan administration initially resisted addressing the ozone hole until American companies like DuPont stood to benefit by selling non-ozone-depleting chemicals — but it captures the kind of triumphant U.S.-led process that Stardust wouldn’t mind seeing repeated.

In 2024, soon after Stardust raised its seed round, Yedvab approached the Swiss-Hungarian diplomat Janos Pasztor and invited him to join the company to advise on the thicket of issues usually simplified as “governance.” These can include technical-seeming questions about how companies should test their technology and who they should seek input from, but they all, at their heart, get to the fundamentally undemocratic nature of solar geoengineering. Given that the atmosphere is a global public good, who on Earth has the right to decide what happens to it?

Pasztor is the former UN assistant secretary-general for climate change, but he was also the longtime leader of the Carnegie Climate Governance Initiative, a nonprofit effort to hammer out consensus answers to some of those questions.

Pasztor hesitated to accept the request. “It was a quadruple challenge,” he told me, speaking from his study in Switzerland. He and his wife frequently attend pro-Palestine demonstrations, he said, and he was reluctant to work with anyone from Israel as long as the country continued to occupy Gaza and the West Bank. Stardust’s status as a private, for-profit enterprise also gave him pause: Pasztor has long advocated for SRM research to be conducted by governments or academics, so that the science can happen out in the open. Stardust broke with all of that.

Despite his reservations, he concluded that the issue was too important — and the lack of any regulation or governance in the space too glaring — for him to turn the company away. “This is an issue that does require some movement,” he said. “We need some governance for the research and development of stratospheric aerosol injection … We don’t have any.”

He agreed to advise Stardust as a contractor, provided that he could publish his report on the company independently and donate his fee to charity. (He ultimately gave $27,000 to UNRWA, the UN agency for Palestinian refugees.)

That summer, Pasztor completed his recommendations, advising Stardust — which remained in stealth mode — to pursue a strategy of “maximum transparency” and publish a website with a code of conduct and some way to have two-way conversations with stakeholders. He also encouraged the company to support a de facto moratorium on geoengineering deployment, and to eventually consider making its intellectual property available to the public in much the same way that Volvo once opened its design for the three-point seatbelt.

His report gestured at Stardust’s strangeness: Here was a company that said it hoped to abide by global research norms, but was, by its very existence, flouting them. “It has generally been considered that private ownership of the means to manage the global atmosphere is not appropriate,” he wrote. “Yet the world is currently faced with a situation of de facto private finance funding [stratospheric aerosol injection] activities.”

Pasztor had initially hoped to publish his report and Stardust’s code of conduct together, he told me. But the company did not immediately establish a website, and eventually Pasztor simply released his report on LinkedIn. Stardust did not put up a website until earlier this year, during the reporting process for a longer feature about the company by the MIT-affiliated science magazine Undark. That website now features Pasztor’s report and a set of “principles,” though not the code of conduct Pasztor envisioned. They are “dragging their feet on that,” he said.

As news of the company trickled out, Stardust’s leaders grew more confident in their methods. In September 2024, Yedvab presented on Stardust’s approach to stratospheric researchers at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s chemical sciences laboratory in Boulder, Colorado. The lab’s director, David Fahey, downplayed the importance of the talk. “There’s a stratospheric community in the world and we know all the long-term members. We’re an open shop,” he said. “We’ll talk to anyone who comes.” Stardust is the only company of its size and seriousness that has shown up, he said.

Stardust is the only company of its size and seriousness working on geoengineering, period, he added. “Stardust really stands out for the investment that they’re trying to make into how you might achieve climate intervention,” he said. “They’re realizing there’s a number of questions the world will need answered if we are going to put the scale of material in the stratosphere that they think we may need to.” (At least one other U.S. company, Make Sunsets, has claimed to release sulfates in the atmosphere and has even sold “cooling credits” to fund its work. But it has raised a fraction of Stardust’s capital, and its unsanctioned outdoor experiments set off such a backlash that Mexico banned all solar geoengineering experiments in response.)

Pasztor continued to work with Stardust throughout this year despite the company’s foot-dragging. He left this summer when he felt like he was becoming a spokesperson for a business that he merely advised. Stardust has more recently worked with Matthew Waxman, a Columbia law professor, on governance issues through the company WestExec Advisors.

Today, Stardust employs a roughly 25-person team that includes physicists, chemists, mechanical engineers, material engineers, and climate experts. Many of them are drawn from Yedvab and Spector’s previous work on Israeli R&D projects.

The company is getting closer to its goals. Yedvab told me that it has developed a proprietary particle that meets its safety and reflectivity requirements. Stardust is now seeking a patent for the material, and it will not disclose the chemical makeup until it receives intellectual property protection. The company claims to be working with a handful of academics around the world on peer-reviewed studies about the particle and broader system, although it declined to provide a list of these researchers on the record.

As Yedvab sees it, the system itself is the true innovation. Stardust has engineered every part of its approach to work in conjunction with every other part — a type of systems thinking that Yedvab and Spector presumably brought from their previous career in government R&D.

Spector described one representative problem: Tiny particles tend to attract each other and clump together when floating in the air, which would decrease the amount of time they spend in the atmosphere, he said. Stardust has built custom machinery to “deagglomerate” the particles, and it has made sure that this dispersion technology is small and light enough to sit on an aircraft flying at or near the stratosphere. (The stratosphere begins at about 26,000 feet over the poles, but 52,000 feet above the equator.)

This integrated approach is part of why Stardust believes it is much further along than any other research effort. “Whatever group that would try to do this, you would need all those types of [people] working together, because otherwise you might have the best chemist, or make the best particle, but it would not fly,” Spector said.

With the new funding, the company believes that its technology could be ready to deploy as soon as the end of this decade. By then, the company hopes to have a particle fabrication facility, a mid-size fleet of aircraft (perhaps a fraction of the size of FedEx’s), and an array of monitoring technology and software ready to deploy.

Even then, its needs would be modest. That infrastructure — and roughly 2 million tons of the unspecified particle — would be all that was required to stop the climate from warming further, Spector said. Each additional million tons a year would reduce Earth’s temperature about half of a degree.

Yet having the technology does not mean that Stardust will deploy it, Yedvab said. The company maintains that it won’t move forward until governments invite it to. “We will only participate in deployment which will be done under adequate governance led by governments,” Yedvab told me. “When you're dealing with such an issue, you should have very clear guiding principles … There are certain ground rules that — I would say in the lack of regulation and governance — we impose upon ourselves.”

He said the company has spoken to American policy makers “on both sides of the aisle” to encourage near-term regulation of the technology. “Policymakers and regulators should get into this game now, because in our view, it's only a matter of time until someone will say, Okay, I'm going and trying to do it,” Yedvab said. “And this could be very dangerous.”

There is a small and active community of academics, scientists, and experts who have been thinking and studying geoengineering for a long time. Stardust is not what almost any of them would have wished a solar geoengineering company to look like.

Researchers had assumed that the first workable SRM system would come from a government, emerging at the end of a long and deliberative public research process. Stardust, meanwhile, is a for-profit company run by Israeli ex-nuclear physicists that spent years in stealth mode, is seeking patent protections for its proprietary particle, and eventually hopes — with the help of the world’s governments — to disperse that particle through the atmosphere indefinitely.

For these reasons, even experts who in other contexts support aggressive research into deploying SRM are quite critical of Stardust.

“The people involved seem like really serious, thoughtful people,” David Keith, a professor and the founding faculty director of the Climate Systems Engineering Initiative at the University of Chicago, told me. “I think their claims about making an inert particle — and their implicit assumption that you can make a particle that is better than sulfates” are “almost certain to be wrong.”

Keith, who is on the scientific advisory board of Reflective, a San Francisco-based nonprofit that aims to accelerate SRM research and technology development, has frank doubts about Stardust’s scientific rationale. Sulfates are almost certainly a better choice than whatever Stardust has cooked up, he said, because we have already spent decades studying how sulfates act. “There’s no such particle that’s inert in the stratosphere,” he told me. “Now maybe they’ve invented something they’ll get a Nobel Prize for that violates that — but I don’t think so.”

He also rejects the premise that for-profit companies should work on SRM. Keith, to be clear, does not hate capitalism: In 2009, he founded the company Carbon Engineering, which developed carbon capture technology before the oil giant Occidental Petroleum bought it for $1.1 billion in 2023. But he has argued since 2018 that while carbon capture is properly the domain of for-profit firms, solar engineering research should never be commercialized.

“Companies always, by definition, have to sell their product,” he told me. “It’s just axiomatic that people tend to overstate the benefits and undersell the risk.” Capitalistic firms excel at driving down the cost of new technologies and producing them at scale, he said. But “for stratospheric aerosol injection, we don’t need it to be cheaper — it’s already cheap,” he continued. “We need better confidence and trust and better bounding of the unknown unknowns.”

Shuchi Talati, who founded and leads the Alliance for Just Deliberation on Solar Geoengineering, is also skeptical. She still believes that countries could find a way to do solar geoengineering for the public good, she told me, but it will almost certainly not look like Stardust. The company is in violation of virtually every norm that has driven the field so far: It is not open about its research or its particle, it is a for-profit company, and it is pursuing intellectual property protections for its technology.

“I think transparency is in every single set of SRM principles” developed since the technology was first conceived, she said. “They obviously have flouted that in their entirety.”

She doubted, too, that Stardust could actually develop a new and totally biosafe chemical, given the amount of mass that would have to be released in the stratosphere to counteract climate change. “Nothing is biosafe” when you disperse it at sufficient scale, she said. “Water in certain quantities is not biosafe.”

The context in which the company operates suggests some other concerns. Although SRM would likely make a poor weapon, at least on short time scales, it is a powerful and world-shaping technology nonetheless. In that way, it’s not so far from nuclear weapons. And while the world has found at least one way to govern that technology — the nonproliferation regime — Israel has bucked it. It is one of only four countries in the world to have never signed the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty. (The others are India, Pakistan, and South Sudan.) Three years ago, the UN voted 152 to 5 that Israel must give up its weapons and sign the treaty.

These concerns are not immaterial to Stardust, given Yedvab and Spector’s careers working as physicists for the government. In our interview, Yedvab stressed the company’s American connections. “We are a company registered in the U.S., working on a global problem,” he told me. “We come from Israel, we cannot hide it, and we do not want to hide it.” But the firm itself has “no ties with the Israeli government — not with respect to funding, not with respect to any other aspect of our work,” he said. “It’s the second chapter in our life,” Spector said.

Stardust may not be connected to the Israeli government, but some of its funders are. The venture capital firm AWZ, which participated in its $15 million seed round, touts its partnership with the Israeli Ministry of Defense’s directorate of defense R&D, and the fund’s strategic advisors include Tamir Pardo, the former director of the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad. “We have no connection to the Israeli government or defense establishment beyond standard regulatory or financial obligations applicable to any company operating in Israel,” a spokesperson for Stardust reiterated in a statement when I asked about the connection. “We are proud that AWZ, along with all of our investors, agrees with our mission and believes deeply in the need to address this crisis.”

One of Stardust’s stated principles is that deployment should be done under “established governance, guided by governments and authorized bodies.” But its documentation provides no detail about who those governments might be or how many governments amount to a quorum.

“The optimal case, in my view, is some kind of a multilateral coalition,” Yedvab said. “We definitely believe that the U.S. has a role there, and we expect and hope also the other governments will take part in building this governance structure.”

Speaking with Pasztor, I observed that the United States and Israel’s actions often deviate sharply from what the rest of the world might want or inscribe in law. What if they decided to conduct geoengineering themselves? “This gets into a pretty hairy geopolitical discussion, but it has to be had,” Pasztor told me. He had discussed similar issues with the company, he said, adding that “at just about every meeting he had” with the team, Stardust’s leaders hoped to “disassociate and distance themselves” from the current Israeli government. “Even when there were suggestions in my recommendations that the first step is to work through ‘your government’ — their thinking was, Okay, we will do it with the Americans,” he said.

He also discussed with the team the risks of the United States going it alone and pursuing stratospheric aerosol injection by itself. That would produce an enormous backlash, Pasztor warned, especially when the Trump administration “is doing everything contrary to what one should do” to fight climate change. “And then doing the U.S. and Israel together — given the current double geopolitical context — that would be even worse,” he said. (“Of course, they could get away with it,” he added. “Who can stop the U.S. from doing it?”)

And that hints at perhaps the greatest risk of Stardust’s existence: that it prevents progress on climate change simply because it will discourage countries from cutting their fossil fuel use. Solar geoengineering’s biggest risk has long seemed to be this moral hazard — that as soon as you can dampen the atmospheric effects of climate change, countries will stop caring about greenhouse gas emissions. It’s certainly something you can imagine the Trump administration doing, I posed to Yedvab.

Yedvab acknowledged that it is a “valid argument.” But the world is so off-track in meeting its goals, he said, that it needs to prepare a Plan B. He asked me to imagine two different scenarios, one where the world diligently develops the technology and governance needed to deploy solar geoengineering over the next 10 years, and another where it wakes up in a decade and decides to crash toward solar geoengineering. “Now think which scenario you prefer,” he said.

Perhaps Stardust will not achieve its goals. Its proprietary particle may not work, or it could prove less effective than sulfates. The company claims that it will disclose its particle once it receives its patent — which could happen as soon as next year, Yedvab and Spector said — and perhaps that process will reveal some defect or other factor that means it is not truly biosafe. The UN may also try to place a blanket ban on geoengineering research, as some groups hope.

Yet Stardust’s mere existence — and the “free driver” problem articulated by Barrett nearly two decades ago — suggests that it will not be the last to try to develop geoengineering technology. There is a great deal of interest in SRM in San Francisco’s technology circles; Pastzor told me that he saw Reflective as “not really different” from Stardust outside of its nonprofit status. “They’re getting all the money from similar types of funders,” he said. “There is stuff happening and we need to deal with it.” (A Reflective representative disputed this characterization, saying that the nonprofit publishes its funders and has no financial incentive to support geoengineering deployment.)

For those who have fretted about climate change, the continued development of SRM technology poses something of a “put up or shut up” moment. One of the ideas embedded in the concept of “climate change” is that humanity has touched everywhere on Earth, that nowhere is safe from human influence. But subsequent environmental science has clarified that, in fact, the Earth has not been free of human influence for millennia. Definitely not since 1492, when the flora and fauna of the Americas encountered those of Afro-Eurasia for the first time — and probably not since human hunters wiped out the Ice Age’s great mammal species roughly 10,000 years ago. The world has over and over again been remade by human hands.

Stardust may not play the Prometheus here and bring this particular capability into humanity’s hands. But I have never been so certain that someone will try in our lifetimes. We find ourselves, once again, in the middle of things.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to include a response from the Reflective team.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

In this emergency episode, Rob unpacks the decision with international supply chain specialist Jonas Nahm.

The Supreme Court just struck down President Trump’s most ambitious tariff plan. What does that ruling mean for clean energy? For the data center boom? For America’s industrial policy?

On this emergency episode of Shift Key, Rob is joined by Jonas Nahm, a professor of economic and industrial policy at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in Washington, D.C. They discuss the ruling, the other authorities that Trump could now use to raise trade levies, and what (if anything) the change could mean for electric vehicles, solar panels, and more.

Shift Key is hosted by Robinson Meyer, the founding executive editor of Heatmap News.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Here is an excerpt from their conversation:

Robinson Meyer: One thing I’m hearing in this list is that there’s five other tariff authorities he could use, and while some of them have restrictions on time or duration or tariff rate, there’s actually still a good amount of like untested tariff authority out there in the law. And if the president and his administration were quite devoted, they would be able to go out there and figure out the limits of 338, or figure out the limits of of 301?

Jonas Nahm: Yeah, I mean, I think one thing to also think about is, what is the purpose of these tariffs, right? And so I think the justifications from the administration have been varied and changed over time. But, you know, they’ve taken in a significant amount of revenue, some $30 billion a month from these tariffs. This was about four times as much as in the Biden administration. And so there is some money coming in from this. And so 122, the 10% immediately would bring back some of that revenue that is otherwise lost. One question is what’s going to happen to refunds from the IEEPA tariffs? Are they going to have to pay this back? It seems like that’s also kind of a court battle that needs to be fought out. And the Supreme Court didn’t weigh in on that. But, you know, the estimates show that if you brought the 122 in at 10%, you would actually recoup a lot of the money that you would otherwise lose and the effective tariff rate in the U.S. Would go back from 10% to about 15%, roughly to where it was before the Supreme Court ruled on it.

Meyer: Has the effect of tariffs from the Trump administration been larger or smaller than what you thought it would be? Not necessarily in the immediate aftermath of “liberation day” because he announced these giant tariffs and then kind of walked some of them back. But the tariff rate has gone up a lot in the past year. Has the effect of that on the economy been more or less than you expected?

Nahm: I think that the industrial policy justification that they have also used is a completely different bucket, right? So you can use this for revenue, and then you can just sort of tax different sectors at different times as long as the sum overall is what you want it to be. From an industrial policy perspective, all of this uncertainty is not very helpful because if you’re thinking about companies making major investment decisions and you have this IEEPA Supreme Court case sort of hanging over the situation for the past year, now we don’t know exactly what they’re going to replace it with, but you’re making a $10 billion decision to build a new manufacturing plant. You may want to sit that out until you know what exactly the environment is and also what the environment is for the components that you need to import, right? So a lot of U.S. imports actually go into domestic manufacturing. And so it’s not just the product that we’re trying to kind of compete with by making it domestically, but also the inputs that we need to make that product here that are being affected.

And so for those kinds of supply chain rewiring industrial policy decisions, you probably want a lot more certainty than we’ve had. And so the Supreme Court ruling against the IEEPA tariff justification is certainly more certainty in all of this. So we’ve now taken that off the list. But we are not clear what the new environment will look like and how long it’s going to stick around. And so from sort of an industrial policy perspective, that’s not really what you want. Ideally, what you would have is very predictable tariffs that give companies time to become competitive without the competition from abroad, and then also a very credible commitment to taking these tariffs away at some point so that the companies have an incentive to become competitive behind the tariff wall and then compete on their own. That’s sort of the ideal case. And we’re somewhat far from the ideal case. Given the uncertainty, given the lack of clarity on whether these things are going to stick around or not, or might be extended forever, and sort of the politics in the U.S. that make it much harder to take tariffs away than to impose them.

You can find a full transcript of the episode here.

Mentioned:

From Heatmap: Clean Energy Looks to (Mostly) Come Out Ahead After the Supreme Court’s Tariff Ruling

This episode of Shift Key is sponsored by ...

Accelerate your clean energy career with Yale’s online certificate programs. Explore the 10-month Financing and Deploying Clean Energy program or the 5-month Clean and Equitable Energy Development program. Use referral code HeatMap26 and get your application in by the priority deadline for $500 off tuition to one of Yale’s online certificate programs in clean energy. Learn more at cbey.yale.edu/online-learning-opportunities.

Music for Shift Key is by Adam Kromelow.

This transcript has been automatically generated.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Robinson Meyer:

[1:25] Hi, I’m Robinson Meyer, the founding executive editor of Heatmap News. It is Friday, February 20. This morning, the Supreme Court threw out President Trump’s most aggressive tariffs, ruling that the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977, usually called IEEPA, does not allow the president to impose broad, indiscriminate tariffs on other countries. Had Congress intended to convey the distinct and extraordinary power to impose tariffs, it would have done so expressly, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote. It was a bit of a stitched together decision. Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Brett Kavanaugh dissented, while Neil Gorsuch, Amy Coney Barrett, and the chief justice ruled with the liberals, although the liberals only concurred with some of the decision. But it takes away a major tool of economic and diplomatic policy making for President Trump.

Robinson Meyer:

[2:12] There were really two sets of tariffs affected by this decision. One was a set of so-called reciprocal tariffs imposed on most countries in the world and set between 10% and 50%. And the second were what Trump called the fentanyl tariffs on China, Mexico, and Canada. Now, the president basically immediately followed up this ruling by saying he would impose a 10% universal tariff on all countries. We’re still trying to understand how exactly he would do that and what it would mean, and we’ll talk about it on the show. But we wanted to have a conversation on an emergency basis here on an emergency shift key episode about what this means for clean energy and what this could also mean for Trump’s industrial policy, such as it is going forward.

Robinson Meyer:

[2:53] Joining us today is Jonas Nahm. He’s an associate professor at the John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in Washington, D.C., and he was recently senior economist for industrial strategy at the White House Council of Economic Advisors. He studies industrial policy, supply chains and trade, and he’s the author of Collaborative Advantage: Forging Green Industries in the New Global Economy. Jonas, welcome to Shift Key.

Jonas Nahm:

[3:18] Thank you for having me. I’m finally on.

Robinson Meyer:

[3:20] You’re finally here. We finally got you. So I think let’s just start here. What do you make of the ruling today and then the president’s kind of successive 10% tariff announcement?

Jonas Nahm:

[3:33] I don’t think this was surprising, right? We had, during the hearings, kind of gotten this impression that the judges were somewhat skeptical, at least, of the ability of the president to use IEEPA to justify these tariffs. And so I think the surprise was really that it took so long. There were lots of rumors floating around for the past couple of months that this would come out any time. And so it finally came, but it sort of came in the form that everyone expected. And the conclusion today was that this is not a tariff statute and that there are other authorities for the president to use to do these things, but this isn’t one of them.

Robinson Meyer:

[4:09] I feel like the most interesting thing, I kind of hinted at this in the intro, was that Brett Kavanaugh, ruled, first of all, that the tariffs were legal, which is kind of crazy, but also that he was like, this is not the proper use of the major questions doctrine, a doctrine he invented to constrain executive authority. But that’s neither here nor there.

Jonas Nahm:

[4:28] Which the liberal justices also didn’t sign on to, right? So it was sort of three people saying this is major questions, and then three people saying this is just, you know, illegal.

Robinson Meyer:

[4:39] Yes. And I think maybe crucially for this audience, Justice Gorsuch cited disapprovingly the Trump administration’s argument that a future president could use IEEPA, the statute in question here, to impose tariffs on fossil fuels or internal combustion engines because it considers climate change to be a national security threat. That was like an argument made by President Trump’s team on behalf of the tariffs to convey their belief that IEEPA had this huge economic policymaking power within it. And Justice Gorsuch was like, no, no, no, it doesn’t let you do that. And it also doesn’t let you impose these tariffs on all these other countries. OK, so I will say I have basically spent every moment up until now not learning about the other tariff authorities. They all are like known by a different number. And it always seemed like people were mentioning a new one. So can you walk us through just like with IEEPA out of the way, what are the other things? Authorities or powers under the law that have been used to impose tariffs on the past or that are seen as kind of being the other powers the president could invoke here if he wanted to keep slapping tariffs on major trading partners?

Jonas Nahm:

[6:00] So one of the big advantages of the IEEPA path for the administration was that it didn’t really involve a lot of procedure. And they had a lot of discretion. Now, no more. But at the time, thinking that they could do this, they had a lot of discretion about how to do this, who to apply this to, which products to exempt, and how to change it very quickly. And so it was basically fairly unconstrained. And so the other authorities all come with more process. And many of them are already in place with more process. So I think one thing to maybe start with is that the IEEPA tariffs are only one part of this tariff stack, and that different products have other tariffs applied to them already. Some of them stack on top of one another, some of them don’t, but there are many kind of authorities in this space that are being used at the same time.

Jonas Nahm:

[6:51] The president came out today and said they’re going to impose 10% universal tariffs under the Section 122, which is from the Trade Act of 1974, which is really to address kind of a large and serious deficit, it can be done very immediately, but it’s capped at 15%. They said they’re going to use 10. The problem for them is that it expires in 150 days unless Congress extends it. So it can sort of stop the revenue loss from taking away the reciprocal and the fentanyl tariffs. It can buy time for permanent fixes, but itself is not really a permanent solution unless there’s congressional buy-in in 150 days, which seems somewhat unlikely. So that’s what they’ve already decided they’re going to use sort of as the bridge to get to these other authorities.

Jonas Nahm:

[7:40] There’s another tariff authority called Section 232, which is about national security related issues. And so there you need to have an investigation and then you can impose these tariffs. We have lots of these investigations ongoing. Some of them are already completed, but pharmaceuticals, robotics, chips, I mean, there’s a bunch of them that are out there. And so what they don’t like about this is that you have to have this investigation so it’s not immediate. it. And so it requires a little bit of process.

Robinson Meyer:

[8:11] Like a Commerce Department investigation, right? This is like a, it’s like a known process where they...

Jonas Nahm:

[8:18] Yeah, and there needs to be a hearing and yes, all of those things. So that’s 232. And then you have Section 301, which is about unfair trade practices. That also requires an investigation and a public hearing, kind of a common period where industry can weigh in. And so you could use that to recreate these tariffs on a country by country basis, the Section 232 tears are mostly at the sectoral level. So the investigations are about sectors that have national security implications, although that has also been stretched widely by this administration. We’ve applied them to kitchen cabinets in this past year, so I don’t immediately follow the national security implications there. But, you know, there is some leeway there in how this is laid out. Section 301 is about unfair trade practices. And then there are the tariffs that were used, you know, almost 100 years ago after the depression, which is Section 338. That gets thrown around a lot. I think it has a lot less procedural constraints attached to it than these other ones. But it’s also untested in modern courts. And this would require the administration to prove that there’s discrimination against U.S. exports. And you could imagine a lot of litigation around how to define discrimination. And so these are sort of the broad authorities that exist and that the administration

Jonas Nahm:

[9:38] has signaled they will rely on. I think mostly the first three.

Robinson Meyer:

[9:41] It does seem like, I think one thing hearing this list is that there’s five other tariff authorities he could use. And while some of them have restrictions on time or duration or tariff rate, there’s actually still a good amount of like untested tariff authority out there in the law and if the president and his administration were like quite devoted they would be able to go out there and, figure out the limits of 338 or figure out the limits of of 301?

Jonas Nahm:

[10:17] Yeah, I mean, I think one thing to also think about is what is the purpose of these tariffs? Right. And so I think the justifications from the administration have been varied and changed over time. But, you know, they’ve taken in a significant amount of revenue, some 30 billion dollars a month from these tariffs. This was about four times as much as in the Biden administration. And so there is some money coming in from this. And so 122, the 10% immediately, would bring back some of that revenue that is otherwise lost. One question is what’s going to happen to refunds from the IEEPA tariffs? Are they going to have to pay this back? It seems like that’s also kind of a court battle that needs to be fought out. And the Supreme Court didn’t weigh in on that. But, you know, the estimates show that if you brought the 122 in at 10%, you would actually recoup a lot of the money that you would otherwise lose and the effective tariff rate in the U.S. Would go back from 10% to about 15%, roughly to where it was before the Supreme Court ruled on it.

Robinson Meyer:

[11:18] Has the effect of tariffs from the Trump administration been larger or smaller than what you thought it would be? Not necessarily in the immediate aftermath of “liberation day”, because he announced these giant tariffs and then kind of walked some of them back. But like the tariff rate has gone up a lot in the past year. Has the effect of that on the economy been more or less than you expected?

Jonas Nahm:

[11:43] I think that the industrial policy justification that they have also used is a completely different bucket. Right. So you can use this for revenue and then you can just sort of tax different sectors at different times as long as the sum overall is what you want it to be. From an industrial policy perspective, all of this uncertainty is not very helpful because if you’re thinking about companies making major investment decisions and you have this IEEPA Supreme Court case sort of hanging over the situation for the past year, now we don’t know exactly what they’re going to replace it with, but you’re making a $10 billion decision to build a new manufacturing plant. You may want to sit that out until you know what exactly the environment is and also what the environment is for the components that you need to import, right? So a lot of U.S. imports actually go into domestic manufacturing. And so it’s not just the product that we’re trying to kind of compete with by making it domestically, but also the inputs that we need to make that product here that are being affected.

Jonas Nahm:

[12:38] And so for those kinds of supply chain rewiring industrial policy decisions, you probably want a lot more certainty than we’ve had. And so the Supreme Court ruling against the IEEPA tariff justification is certainly more certainty in all of this. So we’ve now taken that off the list. But we are not clear what the new environment will look like and how long it’s going to stick around. And so from sort of an industrial policy perspective, that’s not really what you want. Ideally, what you would have is very predictable tariffs that give companies time to become competitive without the competition from abroad, and then also a very credible commitment to taking these tariffs away at some point so that the companies have an incentive to become competitive behind the tariff wall and then compete on their own. That’s sort of the ideal case. And we’re somewhat far from the ideal case. Given the uncertainty, given the lack of clarity on whether these things are going to stick around or not, or might be extended forever, and sort of the politics in the U.S. that make it much harder to take tariffs away than to impose them.

Robinson Meyer:

[15:26] I have heard from Democrats and like Democratic economic policymaker making staff, let’s say, that they really did believe that when Trump announced all these tariffs, that what people said it was going to crash the economy. And the fact that it like hasn’t necessarily crashed the economy has made some of them go, huh, well, maybe tariffs aren’t as bad as we kind of were told they were. And we should consider them as part of a broader economic playbook. Looking over the past year, have you been surprised by how resilient the U.S. economy has been despite all these new trade restrictions that didn’t exist two years ago?

Jonas Nahm:

[16:04] I think the answer to that question really depends on what you’re looking at specifically, right? So if this was supposed to be a manufacturing reshoring tool, in some ways it’s too early to tell whether it’ll work. We’ve seen this during the Biden administration. The Inflation Reduction Act came out. And by the time the election rolled around, a lot of these plants were still under construction. So in some ways, the theory was still untested on whether

Jonas Nahm:

[16:28] that would have changed people’s voting behavior, because we didn’t have enough time. And so in the same way, we don’t have enough time now. And we’ve seen manufacturing job losses over the last year, things have picked up a little bit recently, and sort of capacity utilization is up this month, or last month, rather in the U.S.. But I think that is from using existing plants more rather than building new ones in response to the tariffs. And of course, there are big announcements that have been made where companies that were going to build a plant in Canada are now building it in the U.S.. And some changes in decision-making have occurred as a result of it. But I think to really judge this as a sort of reassuring manufacturing industrial policy, it’s just too early. And I think the uncertainty really also then prolongs the period that it would take for companies to really do this. I mean, you’d want to think about that decision quite carefully. And while a lot of this stuff is still ongoing, I think companies have just avoided making big decisions.

Robinson Meyer:

[17:27] It’s also unclear to me how much of American trade tariffs actually did fall on in terms of specific bilateral relationships. So to be specific, like we talk about these fentanyl tariffs, which is the president’s name for what he said were 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico and 10% tariffs on China and 10% tariffs on Canadian energy exports. And what, Those are big numbers, but what wound up happening in the immediate aftermath of his initial decision was that trade previously authorized under USMCA, the successor to NAFTA, was exempted or wasn’t fully subject to that tariff. And what that meant is that basically, for instance, no Canadian oil exports have ever been subject to this 10% tariff. It’s totally trade as normal between the two countries, at least on an energy basis, and yet. But notionally on the books, there is a threat of a much higher tariff, I suppose, if the president were to change his mind or in the future.

Jonas Nahm:

[18:31] I think you raise a really good point also because the effective tariff rate was around 15 or 16% or so, much lower than some of these headline numbers that were being thrown around. And that’s because we’ve exempted a lot of stuff, right? So coffee prices went up and we exempted Brazilian coffee imports. And we’ve taken other key industries out of this calculation. And USMCA-compliant goods were exempted from the fentanyl tariffs on Canada and Mexico. And so overall, the sort of number of products that are being impacted are much smaller than everything. And one of the interesting questions I think now is, for instance, in the Section 122 10% game that they’re trying to play, the process for exempting and excluding certain products works differently. And so if this really becomes a universal 10%, it would actually affect a lot of things that currently aren’t being tariffed by the reciprocal tariffs. And they don’t have a lot of time. So maybe that also plays into it where they don’t have the capacity to really plan it out strategically. And so if we’re now then moving to a world where a lot of critical inputs into domestic manufacturing are being tariffed at 10% that were previously exempt, that might have some negative consequences for the manufacturers that are trying to survive and all of this uncertainty.

Robinson Meyer:

[19:49] I guess that also removes like a huge opportunity for corruption, because one thing that would happen is the president would take not only like coffee out of the tariff. One thing that would happen is the president wouldn’t only remove tariffs on product categories like coffee, but he would just remove them from companies or put them back on other companies. And it seemed like this huge black box of potential corruption that there just wasn’t a lot of visibility into.

Robinson Meyer:

[20:17] Let’s talk about the sectors that we follow here. So what does this Supreme Court case mean, if anything, for electric vehicles?

Jonas Nahm:

[20:28] Maybe before we jump into this, just to remind everyone, so we’ve taken away one layer of this kind of cake of tariffs that we’ve built here over time. There’s Section 301, there’s Section 232s, there’s anti-dumping and countervailing duties. Sometimes there’s safeguards, Section 201. And so all of those things can apply to the same product. And so we’re sort of taking one piece out of that stack, but it means the others are still there.

Robinson Meyer:

[20:52] And crucially, this is not like a supermarket sheet cake with two layers or even a pound cake like you might.

Jonas Nahm:

[20:59] Make at home. No, it’s a fancy cake.

Robinson Meyer:

[21:00] It’s a Russian honey cake with 12 or 13 layers stacked upon each other of delectable trade-fine goodness.

Jonas Nahm:

[21:09] That’s exactly right. And so if we think about EVs, for instance, the European companies actually aren’t being tariffed under IEEPA. They’re tariffed under Section 232 for autos and parts, which is a totally different legal foundation. And so they are not benefiting from IEEPA going away. They might now get hit with 122s on top of what they were paying previously if that isn’t designed carefully. And so there’s a lot of open questions about what that actually looks like in practice, but it’s certainly not helping them. On the China side, which is probably our bigger concern, is that electric vehicles are already in the Section 301 penalty box and they get 100% on EVs and there’s tariffs on batteries under 301. So IEEPA was there with 10% for these products, but it wasn’t really the significant piece. And so I think there it doesn’t fundamentally change the landscape. But the problem, I think, is more that we have uncertainty and there’s this constant turmoil over what it’s going to be. And we have four meetings between Xi and Trump lined up for the year and he’s supposed to go there at the end of March and lots of uncertainty sort of in the policy space that IEEPA kind of feeds into, but wasn’t really that critical, I think.

Jonas Nahm:

[22:23] And on China specifically, the U.S.TR, the Office of the Trade Representative, launched in the fall a Section 301 investigation on China saying that they hadn’t adhered to the requirements of the phase one trade deal from the first Trump administration. They held the public hearings. They probably have a report ready to go. So they could reimpose also kind of on a national level 301 tariffs on China based on this finding, which could more than offset the loss of the Aiba tariffs.

Robinson Meyer:

[22:53] Okay, next sector. So what does this mean for solar? Because one interesting subplot here that my colleague Matt Zeitlin was talking about earlier today is that after “liberation day”, Wall Street became very convinced that First Solar, this U.S. solar manufacturing firm, was going to be the huge beneficiary of this new Trumpian tariff regime. And it really has not been at all. It’s like, it turned out that a lot of its inputs had new tariffs on them, that it really didn’t affect its business very much. But there are a lot of tariffs on solar. Are they that go back all the way to the Biden administration or the first Trump administration? Were those issued under IEEPA? And what is their current status?

Jonas Nahm:

[23:36] Solar was affected by the IEEPA layer in China, for instance, but there are other tariffs in place that are much more significant. And then on China and also Southeast Asian suppliers, there are anti-dumping and countervailing duties in place that are issued to specific companies. And so the rate kind of depends on which company, but some of them are over 200%. So there you might have a loophole that like a new supplier springs up that isn’t yet affected by this countervailing duty regime. And so they might benefit. But I think there are two, the IEEPA story is only one layer. We had Section 201 safeguards on solar that I think were expiring in February this year. So that layer was ending and now IEEPA is ending. But Section 301 on China and the ADECVDs remain in place and I think are going

Jonas Nahm:

[24:26] to make it unlikely that we see the sudden onslaught of Chinese supply.

Robinson Meyer:

[24:30] Are there any other kind of sectors to talk about here, you know, really affected by this or, I don’t know, data center inputs?

Jonas Nahm:

[24:41] Wind, I think, was exposed to the IEEPA layer to some degree, but I think the other question is more broadly, what are we doing with the domestic wind industry? There’s also a 232 national security investigation that is ongoing on wind that they could switch to as a justification, both on wind turbines and turbine parts. And so there, I think we might see some sort of temporary IEEPA relief, especially for inputs like metals and so on that are now coming in, perhaps at different prices. I don’t know if that can really help the wind industry overcome the broader headwinds that they’re facing with this administration. But, you know, if there is a real positive impact, I would expect them to very quickly switch to the 232 justification to make up for it. I think on data centers, it’s interesting.

Jonas Nahm:

[25:29] Data centers import a huge amount of equipment, right? So servers, networking, equipment, power distribution, cooling, switch, there’s all this stuff that goes into a data center. And if IEEPA went away and nothing replaces it, that might actually be a meaningful relief for a lot of that stack. But now under this 10% 122 surcharge, it’s coming back. And if some of these exemptions that we had in place for some of these components in order to support domestic data center build out are not included, and we have to see how they actually implement this, this could be quite negative. But to me, this is really a story at this point of thinking about this way more as a revenue source than a strategic industrial policy that’s trying to reshore certain sectors. And the more we change it up and switch from one authority to another, the more it becomes a revenue story because the actual economic impact in terms of reshoring is going to be less and less.

Robinson Meyer:

[26:22] So one thing I’m taking from this conversation is that while clean energy and energy inputs might get a tiny bit of relief, largely they were already subject to this existing stack of pre-existing tariff authorities under other laws. And so they might benefit from like some economic tailwinds from this, but it’s not like Chinese or Southeast Asian solar panels are going to suddenly

Robinson Meyer:

[26:50] be available in the United States at cost. Stepping back then, what is your read of how this ruling fits into the Trump administration’s trade policy, and I think broadly, America’s attempt to formulate some kind of industrial policy that now started with the first Trump administration, was continued and changed by the Biden administration, and now soldiers on under the second Trump administration.

Jonas Nahm:

[27:19] If I think about this broadly in terms of sort of economic policymaking, the tariffs are one tool you can use to shape the nature and structure and composition of the domestic economy. In many ways, what I think is much more important is what do you do behind the tariff wall to really help companies build competitive manufacturing capacity, for instance, right? And the tariffs themselves are not really enough to do much there. And a lot of the incentives and sort of support that, for instance, the Inflation Reduction Act included, that have been taken away or it’s shortened significantly. And so we’re doing kind of less on the domestic economy and we’re doing more at the border. But I think ideally you would do

Jonas Nahm:

[28:08] Much more certainty at the border, and then combine it with a domestic strategy. And I think we’re seeing some of this now happen kind of in the critical mineral space, you know, Vault, Forge, all these kinds of new initiatives that are being pushed out by the administration to look at the demand side, and kind of create more stable markets for these technologies, for instance. So slow beginnings of kind of the supply side and demand side match in pairing different industrial policy tools. But in some ways, I think this tariff game has been a huge distraction from the actual work that we need to do on vocational training, on financing for manufacturing, on creating stable demand for these technologies that we want to make domestically so that companies can get financing and invest. And so looking at trade policy in that kind of broader picture, it looks more like a revenue policy than an industrial policy because it’s not really coordinated with these other elements.

Robinson Meyer:

[29:05] I think we’ll have to leave it there. Jonas Nahm, thank you so much.

Jonas Nahm:

[29:09] Thank you for having me on.

Robinson Meyer:

[29:14] And that will do it for us today. Thank you so much for joining us on this special weekend emergency edition of Shift Key. If you enjoyed Shift Key, then leave us a review or send this episode to your friends. You can follow me on X or Bluesky or LinkedIn, all of the above, under my name, Robinson Meyer. We’ll be back next week with at least one new episode of Shift Key for you until then Shift Key is a production of Heatmap News. Our editors are Jillian Goodman and Nico Lauricella, multimedia editing audio engineering is by Jacob Lambert and by Nick Woodbury. Our music is by Adam Kromelow. Thanks so much for listening and see you next week.

NineDot Energy’s nine-fiigure bet on New York City is a huge sign from the marketplace.

Battery storage is moving full steam ahead in the Big Apple under new Mayor Zohran Mamdani.

NineDot Energy, the city’s largest battery storage developer, just raised more than $430 million in debt financing for 28 projects across the metro area, bringing the company’s overall project pipeline to more than 60 battery storage facilities across every borough except Manhattan. It’s a huge sign from the marketplace that investors remain confident the flashpoints in recent years over individual battery projects in New York City may fail to halt development overall. In an interview with me on Tuesday, NineDot CEO David Arfin said as much. “The last administration, the Adams administration, was very supportive of the transition to clean energy. We expect the Mamdani administration to be similar.”

It’s a big deal given that a year ago, the Moss Landing battery fire in California sparked a wave of fresh battery restrictions at the local level. We’ve been able to track at least seven battery storage fights in the boroughs so far, but we wouldn’t be surprised if the number was even higher. In other words, risk remains evident all over the place.

Asked where the fears over battery storage are heading, Arfin said it's “really hard to tell.”

“As we create more facts on the ground and have more operating batteries in New York, people will gain confidence or have less fear over how these systems operate and the positive nature of them,” he told me. “Infrastructure projects will introduce concern and reasonably so – people should know what’s going on there, what has been done to protect public safety. We share that concern. So I think the future is very bright for being able to build the cleaner infrastructure of the future, but it's not a straightforward path.”

In terms of new policy threats for development, local lawmakers are trying to create new setback requirements and bond rules. Sam Pirozzolo, a Staten Island area assemblyman, has been one of the local politicians most vocally opposed to battery storage without new regulations in place, citing how close projects can be to residences, because it's all happening in a city.

“If I was the CEO of NineDot I would probably be doing the same thing they’re doing now, and that is making sure my company is profitable,” Pirozzolo told me, explaining that in private conversations with the company, he’s made it clear his stance is that Staten Islanders “take the liability and no profit – you’re going to give money to the city of New York but not Staten Island.”

But onlookers also view the NineDot debt financing as a vote of confidence and believe the Mamdani administration may be better able to tackle the various little bouts of hysterics happening today over battery storage. Former mayor Eric Adams did have the City of Yes policy, which allowed for streamlined permitting. However, he didn’t use his pulpit to assuage battery fears. The hope is that the new mayor will use his ample charisma to deftly dispatch these flares.

“I’d be shocked if the administration wasn’t supportive,” said Jonathan Cohen, policy director for NY SEIA, stating Mamdani “has proven to be one of the most effective messengers in New York City politics in a long time and I think his success shows that for at least the majority of folks who turned out in the election, he is a trusted voice. It is an exercise that he has the tools to make this argument.”

City Hall couldn’t be reached for comment on this story. But it’s worth noting the likeliest pathway to any fresh action will come from the city council, then upwards. Hearings on potential legislation around battery storage siting only began late last year. In those hearings, it appears policymakers are erring on the side of safety instead of blanket restrictions.