You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

It’s been just over a week since one of the 350-foot-long blades of a wind turbine off the Massachusetts coast unexpectedly broke off, sending hunks of fiberglass and foam into the waters below. As of Wednesday morning, cleanup crews were still actively removing debris from the water and beaches and working to locate additional pieces of the blade.

The blade failure quickly became a crisis for residents of Nantucket, where debris soon began washing up on the island’s busy beaches. It is also a PR nightmare for the nascent U.S. offshore wind industry, which is already on the defensive against community opposition and rampant misinformation about its environmental risks and benefits.

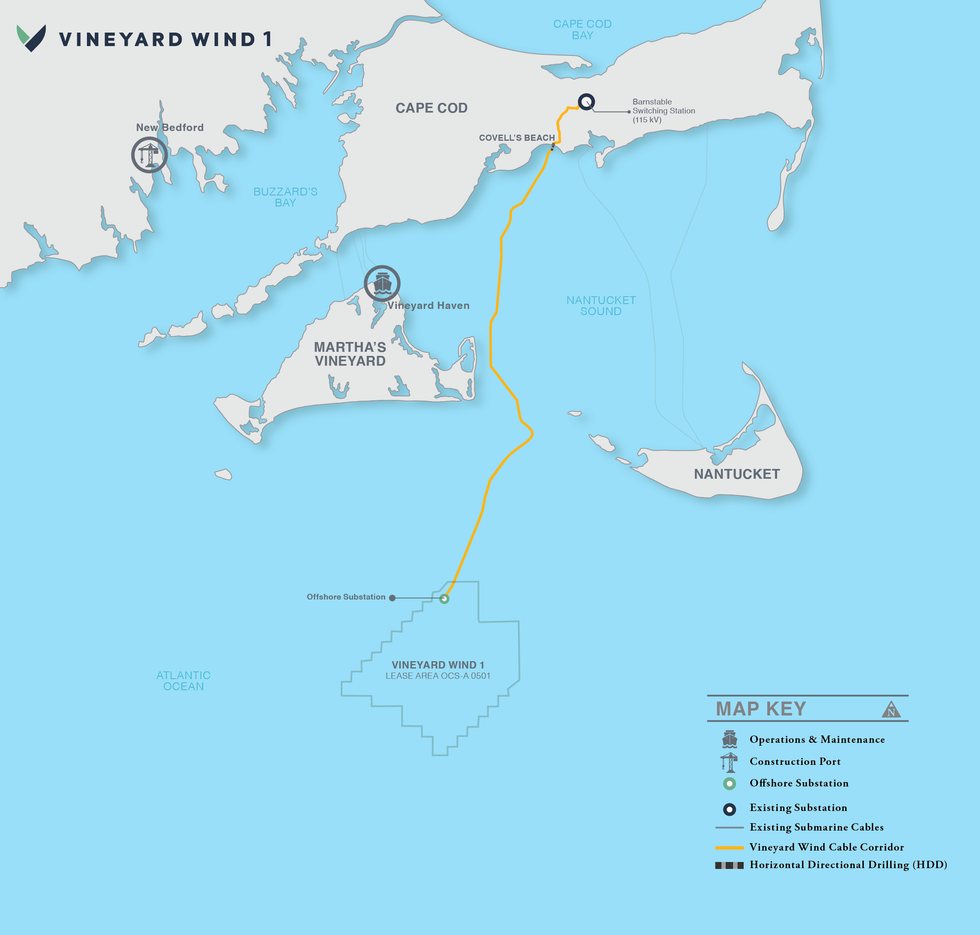

The broken turbine is part of Vineyard Wind 1, which is being developed by Avangrid and Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners. The project was still under construction when the breakage occurred, but it was already the largest operating offshore wind farm in the US, with ten turbines sending power to the New England Grid as of June. The plan is to bring another 52 online, which will produce enough electricity to power more than 400,000 homes. Now both installation and power generation have been paused while federal investigators look into the incident.

There’s still a lot we don’t know about why this happened, what the health and safety risks are, and what it means for this promising clean energy solution going forward. But here’s everything we’ve learned so far.

Vineyard Wind

On the evening of Saturday, July 13, Vineyard Wind received an alert that there was a problem with one of its turbines. The equipment contains a “delicate sensoring system,” CEO Klaus Moeller told the Nantucket Select Board during a public meeting last week. Though he did not describe what the alert said, he added that “one of the blades was broken and folded over.” Later at the meeting, a spokesperson for GE Vernova, which manufactured and installed the turbines, said that “blade vibrations” had been detected. About a third of the blade, or roughly 120 feet, fell into the water.

Two days later, Vineyard Wind contacted the town manager in Nantucket to explain that modeling showed the potential for debris from the blade to travel toward the island. Sure enough, fiberglass shards and other scraps began washing up on shore the next day, and all beaches on the island’s south shore were quickly closed to the public.

On Thursday morning, another large portion of the damaged blade detached and fell into the ocean. Monitoring and recovery crews continued to find debris throughout the area over the weekend. The beaches have since reopened, but visitors have been advised to wear shoes and leave their pets at home as cleanup continues.

During GE’s second quarter earnings call on July 24, GE Vernova CEO Scott Strazik and Vice President of Investor Relations Michael Lapides said the company had identified a “material deviation” as the cause of the accident, and that the company is continuing to work on a "root cause analysis" to get to the bottom of how said deviation happened in the first place.

The turbine was one of GE’s Haliade-X 13-megawatt turbines, which are manufactured in Gaspé, Canada, and it was still undergoing post-installation testing by GE when the failure occurred — that is, it was not among those sending power to the New England grid. This was actually the second issue the company has had at this particular turbine site. One of the original blades destined for the site was damaged during the installation process, and the one that broke last week was a replacement, Craig Gilvard, Vineyard Wind’s communications director, told the New Bedford Light.

By Vineyard Wind’s account at the meeting last week, the accident triggered an automatic shut down of the system and activated the company’s emergency response plan, which included immediately notifying the U.S. Coast Guard, the federal Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement, and regional emergency response committees.

Moeller, the CEO, said during the meeting that the company worked with the Coast Guard to immediately establish a 500 meter “safety zone” around the turbine and to send out notices to mariners. According to the Coast Guard’s notice log, however, the safety zone went into effect three days later. In response to my questions, the Coast Guard confirmed that the zone was established around 8pm that night and announced to mariners over radio broadcast.

Two days after the turbine broke, on Monday, Vineyard Wind contacted the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration for aid in modeling where the turbine debris would travel in the water. The agency estimated pieces would likely make landfall in Nantucket that day. Vineyard Wind put out a press release about the accident and subsequently contacted the Nantucket town manager. At the Nantucket Select Board meeting last week, Moeller said the company followed regulatory protocols but that there was “really no excuse” for how long it took to inform the public, and said, “we want to move much quicker and make sure that we learn from this.”

The Interior Department’s Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement has ordered the company to cease all power production and installation activities until it can determine whether this was an isolated incident or affects other turbines.

By Tuesday, Vineyard Wind said it had deployed two small teams to Nantucket in addition to hiring a local contractor to remove debris on the island. The company later said it would “increase its local team to more than 50 employees and contractors dedicated to beach clean-up and debris recovery efforts.”

GE Vernova is responsible for recovering offshore debris and has not published any public statements about the effort. In response to a list of questions, a GE Vernova spokesperson said, “We continue to work around the clock to enhance mitigation efforts in collaboration with Vineyard Wind and all relevant state, local and federal authorities. We are working with urgency to complete our root cause analysis of this event.”

There have been no reported injuries as a result of the accident.

Vineyard Wind and GE Vernova have stressed that the debris are “not toxic.” At the Select Board meeting, GE’s executive fleet engineering director Renjith Viripullan said that the blade is made of fiberglass, foam, and balsa wood. It is bonded together using a “bond paste,” he said, and likened the blade construction to that of a boat. “That's the correlation we need to think about,” he said.

One of the board members asked if there was any risk of PFAS contamination as a result of the accident. Viripullan said he would need to “take that question back” and follow up with the answer later. (This was one of the questions I asked GE, but the company did not respond to it.)

That being said, the debris poses some dangers. Photos of cleanup crews posted to the Harbormaster’s Facebook page show workers wearing white hazmat suits. Vineyard Wind said “members of the public should avoid handling debris as the fiber-glass pieces can be sharp and lead to cuts if handled without proper gloves.”

Though members of the public raised concerns at the meeting and to the press that fiberglass fragments in the ocean threaten marine life and public health, it is not yet clear how serious the risks are, and several efforts are underway to further assess them. Vineyard Wind is developing a water quality testing plan for the island and setting up a process for people to file claims. GE hired a design and engineering firm to conduct an environmental assessment, which it will present at a Nantucket Select Board meeting later this week. The Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection has requested information from the companies about the makeup of the debris to evaluate risks, and the Department of Fish and Game is monitoring for impacts to the local ecosystem.

As of last Wednesday morning, Vineyard Wind had collected “approximately 17 cubic yards of debris, enough to fill more than six truckloads, and several larger pieces that washed ashore.” It is not yet known what fraction of the turbine that fell off has been recovered. Vineyard Wind did not respond to a request for the latest numbers in time for publication, but I’ll update this piece if I get a response.

Yes. In May, a blade on the same model of turbine, the GE Haliade-X, sustained damage at a wind farm being installed off the coast of England called Dogger Bank. At the Nantucket Select Board meeting, a spokesperson for GE said the Dogger Bank incident was “an installation issue specific to the installation of that blade” and that “we don’t think there’s a connection between that installation issue and what we saw here.” Executives emphasized this point during the earnings call and chalked up the Dogger Bank incident to “an installation error out at sea.”

Several blades have also broken off another GE turbine model dubbed the Cypress at wind farms in Germany and Sweden. After the most recent incident in Germany last October, the company used similar language, telling reporters that it was working to “determine the root cause.”

A “company source with knowledge of the investigations” into the various incidents recently told CNN that “there were different root causes for the damage, including transportation, handling, and manufacturing deviations.”

GE Vernova’s stock price fell nearly 10% last Wednesday.

The backlash was swift. Nantucket residents immediately wrote to Nantucket’s Select Board to ask the town to stop the construction of any additional offshore wind turbines. “I know it's not oil, but it's sharp and maybe toxic in other ways,” Select Board member Dawn Holgate told company executives at the meeting last week. “We're also facing an exponential risk if this were to continue because many more windmills are planned to be built out there and there's been a lot of concern about that throughout the community.”

The Select Board plans to meet in private on Tuesday night to discuss “potential litigation by the town against Vineyard Wind relative to recovery costs.”

“We expect Vineyard Wind will be responsible for all costs and associated remediation efforts incurred by the town in response to the incident,” Elizabeth Gibson, the Nantucket town manager said during the meeting last week.

The Aquinnah Wampanoag tribe is also calling for a moratorium on offshore wind development and raised concerns about the presence of fiberglass fragments in the water.

On social media, anti-wind groups throughout the northeast took up the story as evidence that offshore wind is “not green, not clean.” Republican state representatives in Massachusetts cited the incident as a reason for opposing legislation to expedite clean energy permitting last week. Fox News sought comment from internet personality and founder of Barstool Sports David Portnoy, who owns a home on Nantucket and said the island had been “ruined by negligence.” The Texas Public Policy Foundation, a nonprofit funded by oil companies and which is backing a lawsuit against Vineyard Wind, cited the incident as evidence that the project is harming local fishermen. The First Circuit Court of Appeals is set to hear oral arguments on the case this Thursday.

Meanwhile, environmental groups supportive of offshore wind tried to do damage control for the industry. “Now we must all work to ensure that the failure of a single turbine blade does not adversely impact the emergence of offshore wind as a critical solution for reducing dependence on fossil fuels and addressing the climate crisis,” the Sierra Club’s senior advisor for offshore wind, Nancy Pyne, wrote in a statement. “Wind power is one of the safest forms of energy generation.”

This story was last updated July 24 at 3:15 p.m. The current version contains new information and corrects the location where the turbine blades are produced. With assistance from Jael Holzman.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Here’s what stood out to former agency staffers.

The Department of Energy unveiled a long-awaited internal reorganization of the agency on Thursday, implementing sweeping changes that Secretary of Energy Chris Wright pitched as “aligning its operations to restore commonsense to energy policy, lower costs for American families and businesses.”

The two-paragraph press release, which linked to a PDF of the new organizational chart, offered little insight into what the changes mean. Indeed, two sources familiar with the rollout told me the agency hadn’t even held a town hall to explain the overhaul to staffers until sometime Friday. (Both sources spoke on condition of anonymity out of fear of reprisals.)

After conversations with multiple former agency staffers, including a senior political appointee who helped lead the Biden-era reorganization in 2022, here’s what stood out to me:

The spring 2022 overhaul Jennifer Granholm, former President Joe Biden’s secretary of energy, oversaw came with a detailed legal memo and extensive explanations about what the changes would mean.

“Overall, this seems sloppy,” the former senior staffer who led that process told me this morning. “If you’re trying to carry out a very coherent energy dominance strategy, you’d at least explain which boxes are moving where and what’s sitting under those boxes.”

Announcing the changes with so little detail, the former official said, “seems like a fundamental lack of leadership.”

“This, to me, just seems reckless,” the appointee continued. “People who are sitting within these offices don’t know where they’re going to work virtually on Monday.”

That, of course, may change by the end of today once the Energy Department holds its town hall meeting.

It’s unusual for an office at the agency to report directly to the secretary. Those that do typically straddle multiple types of responsibilities within the agency. For example, the Office of Technology Transitions reported directly to Granholm under the Biden administration because its purview fell under both research and deployment. The Office of Policy functions similarly. But the newly-created Office of Critical Minerals and Energy Innovation absorbed not only various mining-related sections of the agency, but also the now-defunct Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. That puts a lot of money and grant-making powers under the new office.

Leading the Office of Critical Minerals and Energy Innovation will be Audrey Robertson, who was confirmed last month as the assistant secretary for the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. A former investment banker and oil executive, Robertson served on the board of directors of Wright’s former company, the fracking giant Liberty Energy, until earlier this year. Another agency source familiar with the organization said “it makes no sense for this office not to answer to an undersecretary of energy.”

“Audrey is Wright’s person,” the source told me.

That, the other former agency official told me, creates some political liabilities for Wright.

“For departmental oversight reasons, that’s a lot of grant-making money and authorities that typically you’d want to layer under additional oversight before it goes to the secretary,” the ex-official said. “This is the thing that sticks out like a sore thumb.”

All that said about the new Office of Critical Minerals and Energy Innovation, no one can blame Wright for wanting to consolidate some of the bureaucracy. One way to read the decision to eliminate certain offices, such as the Office of Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains or the Office of State and Community Energy Programs, is that the new administration wanted to undo the changes made under its predecessor in 2022. While manufacturing work included a lot of what the U.S. is doing with batteries, funding for that work fell under the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy in the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

“A lot of the moves that they’re doing to re-consolidate offices aligns with what was technically under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which directed battery work to go through EERE,” one of the sources told me. “So some of this is realignment back to the original congressional direction.”

The stop-gap funding bill that reopened the government after the longest shutdown in history included a measure to prevent any dismissals until January 30.

But it’s unclear whether the agency plans to terminate workers as part of the reorganization starting in February.

In a sign that the Trump administration is taking efforts to commercialize fusion energy technology more seriously, the reorganization gives fusion its own office, moving the work out of the Office of Science.

“Overall this is a win for the private-fusion sector, and further cements a move from a discovery-based research model to milestone-driven, commercialization-focused policy,” Stuart Allen, the chief executive of the investment company FusionX Group, wrote in a post on LinkedIn. “All signs point to a federal strategy increasingly aligned and enmeshed with the rapid advancement of fusion energy.”

Under the new structure, geothermal and fossil fuels will live together under the new Hydrocarbons and Geothermal Energy Office.

There are some obvious synergies. The new generation of geothermal startups racing toward commercialization rely on drilling techniques such as fracking to tap into hot rocks in places that conventional companies couldn’t. Oil and gas companies are excited about the industry; Sage Geosystems, one of the big players, is led by the former head of Shell’s fracking division. And notably, most of the big companies, including Sage, Fervo Energy, and XGS Energy (whom I have written about twice recently in these pages) are all headquartered in Big Oil’s capital of Houston, Texas.

Nuclear power has long had its own office at the Energy Department, and that won’t change. But you’d think that the other source of clean baseload power that the Trump administration has anointed as one of its preferred generating sources might get slotted in with geothermal. Instead, however, hydropower is in Robertson’s mega-office.

Unsurprisingly, the bulk of the Energy Department’s work that deals with the nation’s nuclear arsenal was largely left untouched by the changes. Perhaps the agency had enough drama from the Department of Government Efficiency’s dismissals of critical workers in the early days of the administration, which led to an embarrassing effort to reverse the firings.

As was widely expected, the reorg killed the Biden-era Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations, which the new administration had already gutted. What becomes of key programs that office managed is still a mystery. Chief among them: the hydrogen hubs.

The Energy Department yanked funding for the two regional hubs on the West Coast last month, as Heatmap’s Emily Pontecorovo reported at the time. A leaked list that the administration has yet to confirm as real proposed defunding all seven of the hubs. It’s unclear whether that may happen. If it doesn’t, it’s unclear where those billions of dollars may go. The most obvious place is under Robertson’s portfolio, ballooning the budget under her control by billions.

When Wright announced the first totally new loan issued under the agency’s in-house lender earlier this week, he trumpeted his new approach the Loan Programs Office. He wanted to refashion the entity with its lending authority of nearly $400 billion as a source of funding primarily for the nuclear industry. The first big loan issued Tuesday afternoon went to utility giant Constellation to finance the restart of the functional reactor at the Three Mile Island nuclear station. But at a press conference last month, Wright hinted at the new branding, as Emily called in this piece. It’s now the Office of Energy Dominance Financing.

The new office isn’t just the LPO, however. The $2.5 billion Transmission Facility Financing Program will also fall under the new so-called EDF — an acronym it will aptly share with France’s biggest utility, which came under state control recently as part of Paris’ efforts to refurbish and expand the country’s vast nuclear fleet.

I’ll leave it to my source to level a critique at my colleagues in this industry:

“Even in The New York Times today there’s an article that says all these offices are eliminated,” one of the sources told me. “Their names were eliminated, but a lot of the projects for whatever remains that they haven’t terminated are just being reassigned.” The Wall Street Journal had a similar angle.

The actual thing to watch for, the source said, was how job descriptions change.

“What’s going to be more telling is when they have a new, updated mission of the Office of Electricity or a new, updated mission of the Office of Critical Minerals and Energy Innovation.”

The United Nations climate conference wants you to think it’s getting real. It’s not total B.S.

How to transition away from fossil fuels. How to measure adaptation. How to confront the gap between national climate plans and the Paris Agreement goals. How to mine critical minerals sustainably and fairly.

How to get things done — not just whether they should get done — was front and center at this year’s United Nations climate conference, a marked shift from the annual event’s proclivity for making broad promises to wrestling with some of the tougher realities of keeping global warming in check.

Friday is the last official day of the two-week gathering known as COP30, taking place on the edge of the Amazon rainforest in Belém, Brazil, although probably not the actual end of it. Despite early assurances from the Brazilian government that this year’s conference would finish on time, delegates are still hashing out a final decision text and are likely to keep at it until at least Saturday.

The Brazilian leadership and other COP veterans have framed this as an “implementation COP,” where parties to the Paris Agreement “move from pledges to action” and similar clichès. It’s certainly not the first time these words have been used at COP. The Paris Agreement itself was billed as “enhancing the implementation” of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, the foundational treaty underlying these annual negotiations.

“Action” may be a stretch to describe what ultimately happened this year. As is the case at every COP, the provision of finance, or lack thereof, from developed to developing countries dominated the discussion, preventing progress on other agenda items. “Climate finance just remains this ongoing obstacle,” Rachel Cleetus, a senior policy director for the Union of Concerned Scientists, told me. Global south countries and small island states argue they simply cannot increase their ambition, or work on adaptation, without finance. The conference’s repeated failure to come to terms with that is probably the biggest counterpoint to the idea that these meetings have become more grounded in reality.

It remains to be seen which, if any, of the efforts to work out the details of the transition will make it into the final agreement, but the success of these annual gatherings should not only be measured by what’s in the text.

Here are three key ways Belém has already pushed the conversation forward.

During a speech at the start of the conference, Brazil’s President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva proclaimed that it is “impossible to discuss the energy transition without talking about critical minerals, essential to make batteries, solar panels, and energy systems.”

Never before had the negotiations broached the subject of all of the industrial earth-moving implicit in the fight against climate change. By the end of the first week, however, one of the working groups had released a draft text that acknowledged “the social and environmental risks associated with” extracting and processing critical minerals.

A later revision of the document added a note about “enabling fair access to opportunities and fair distribution of benefits of value addition,” a reference to breaking the pattern of rich countries extracting minerals cheaply from the Global South while keeping the more profitable processing and manufacturing of those minerals at home. (As of Friday morning, however, references to “critical minerals” were erased from the text.)

The text was released by the Just Transition Work Program, a newer workstream at the conference that was established at COP27 in Egypt. Outside of the critical minerals note, there was a larger push to get Just Transition program as a whole more grounded in reality. This area of the negotiations focuses on ensuring the goals of the Paris Agreement are achieved fairly and equitably, with recognition that the transition will happen at a different pace in different countries, with different implications for each one’s economy. It was primarily established as a forum for countries to exchange ideas and information, with biannual meetings.

At COP30, however, the G77, China, and many global south countries began pushing to turn it into more of an action-oriented group that guides the global transition and tracks progress using agreed-upon metrics.

The Just Transition mechanism is not to be confused with the much-talked-about roadmap to transition away from fossil fuels, although the two are closely tied.

Two years ago, the final agreement at COP28 in Dubai made history with the first-ever call for “transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner.” Last year, however, that edict was dropped, as negotiations over a new climate finance target took precedence. Now it’s been revived, with robust support from countries to build on the statement with a more fleshed-out plan. Phasing out fossil fuels has vastly different implications for different countries, some of whose economies are deeply dependent on revenue from their fossil resources. The roadmap would start to work through what it would really mean to coordinate the effort.

Once again, the message came from the top. “We need roadmaps that will enable humankind, in a fair and planned manner, to overcome its dependence on fossil fuels, halt and reverse deforestation, and mobilize resources to achieve these goals,” Brazil’s Silva said in a speech at the opening of the conference.

This past Tuesday, a coalition of a whopping 82 countries came out in support of this planning effort, pressing for it to be included in the final decision text. “This is a global coalition, with global north and global south countries coming together and saying with one voice: this is an issue which cannot be swept under the carpet,” Ed Miliband, the UK’s energy secretary, said during a press conference that day.

Several more countries have joined since, bringing the count to 88 — nearly half of the 195 parties to the Paris Agreement. The biggest fossil fuel emitters, such as China, India, and Saudi Arabia, are not on board, however. As of Friday morning, all mentions of fossil fuels, let alone a roadmap, have been scrubbed from the draft decision text. Still, the huge coalition backing the roadmap is a sign of a growing and potentially powerful consensus.

One of the big questions looming over this year’s conference was whether and how countries would address their utter failure to live up to the Paris Agreement’s goal to keep warming “well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels,” let alone the more ambitious target of 1.5 degrees.

A report issued by the United Nations Environment Program just before the talks began concluded that countries’ latest climate pledges, known as their “nationally determined contributions,” or NDCs, would put the planet on a path to warm at least 2.3 degrees by the end of the century. It also stated definitively that global average temperatures would exceed 1.5 degrees of warming.

This wasn’t news — scientists have previously concluded that exceeding 1.5 degrees is basically guaranteed. “But this is the first time we saw it so bluntly in the UN report,” Cleetus told me. “So that was a pretty sobering backdrop coming into this COP.”

All countries were supposed to submit updated NDCs this year that contained targets for 2035, but more than 70 have failed to do so, including India, one of the world’s biggest emitters.

Island states, backed by Latin American nations and the EU, wanted the conference to make some kind of declaration that countries’ current pledges are not sufficient and should be revised. The draft text issued this morning, while acknowledging the insufficiencies of NDCs, does not spell out the implications or required response as bluntly as many want to see.

It does, however, introduce an important new concept that could become a key part of the negotiations in the future. For the first time, the text references a resolve to “limit both the magnitude and duration of any temperature overshoot.” This not only acknowledges that it’s possible to bring temperatures back down after warming surpasses 1.5 degrees, but that the level at which temperatures peak, and the length of time we remain at that peak before the world begins to cool, are just as important. The statement implies the need for a much larger conversation about carbon removal that has been nearly absent from the annual COPs, but which scientists say that countries must have if they are serious about the Paris Agreement goals.

"If countries (or the UNFCCC) want to keep talking about reaching 1.5C, they need to embrace net-negative emissions, moving even beyond net-zero,” Oliver Geden, a senior fellow at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs, and an IPCC report author, told me. “If they don't want to do this, then talking about reaching 1.5°C is not credible anymore.”

Things in Sulphur Springs are getting weird.

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton is trying to pressure a company into breaking a legal agreement for land conservation so a giant data center can be built on the property.

The Lone Star town of Sulphur Springs really wants to welcome data center developer MSB Global, striking a deal this year to bring several data centers with on-site power to the community. The influx of money to the community would be massive: the town would get at least $100 million in annual tax revenue, nearly three times its annual budget. Except there’s a big problem: The project site is on land gifted by a former coal mining company to Sulphur Springs expressly on the condition that it not be used for future energy generation. Part of the reason for this was that the lands were contaminated as a former mine site, and it was expected this property would turn into something like a housing development or public works project.

The mining company, Luminant, went bankrupt, resurfaced as a diversified energy company, and was acquired by power giant Vistra, which is refusing to budge on the terms of the land agreement. After sitting on Luminant’s land for years expecting it to be used for its intended purposes, the data center project’s sudden arrival appears to have really bothered Vistra, and with construction already underway, the company has gone as far as to send the town and the company a cease and desist.

This led Sulphur Springs to sue Vistra. According to a bevy of legal documents posted online by Jamie Mitchell, an activist fighting the data center, Sulphur Springs alleges that the terms of the agreement are void “for public policy,” claiming that land restrictions interfering with a municipality’s ability to provide “essential services” are invalid under prior court precedent in Texas. The lawsuit also claims that by holding the land for its own use, Vistra is violating state antitrust law by creating an “energy monopoly.” The energy company filed its own counterclaims, explicitly saying in a filing that Sulphur Springs was part of crafting this agreement and that “a deal is a deal.”

That’s where things get weird, because now Texas is investigating Luminant over the “energy monopoly” claim raised by the town. It’s hard not to see this as a pressure tactic to get the data center constructed.

In an amicus brief filed to the state court and posted online, Paxton’s office backs up the town’s claim that the land agreement against energy development violates the state’s antitrust law, the Texas Free Enterprise and Antitrust Act, contesting that the “at-issue restriction appears to be perpetual” and therefore illegally anti-competitive. The brief also urges the court not to dismiss the case before the state completes its investigation, which will undoubtedly lead to the release of numerous internal corporate documents.

“Sulphur Springs has alleged a pattern of restricting land with the potential for energy generation, with the effect of harming competition for energy generation generally, which would necessarily have the impact of increasing costs for both Sulphur Springs and Texas consumers generally,” the filing states. “Evaluating the competitive effects of Luminant’s deed restrictions as well as the harm to Texans generally is a fact-intensive matter that will require extensive discovery.”

The Texas attorney general’s office did not respond to multiple requests for comment on the matter. It’s worth noting that Paxton has officially entered the Republican Senate primary, challenging sitting U.S. Senator John Cornyn. Contrary to his position in this case, Paxton has positioned himself as a Big Tech antagonist and fought the state public utilities commission in pursuit of releasing data on the crypto mining industry’s energy use.