You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

We chat with data scientist Clayton Page Aldern about neuroplasticity, the problem of consciousness, and his new book, The Weight of Nature.

Thinking is physical. Thankfully, one of the many wonderful things about the human brain is that we don’t have to confront this unsettling fact very much — that the environment around us shapes our perceptions and reactions, that all human experience is the result of secreted hormones and synaptic transmission. In other words, our brains let us think we’re in charge.

Unfortunately, as with so many other things, climate change is interfering. “As the environment changes, you should expect to change too,” writes author, neuroscientist, and Grist senior data scientist Clayton Page Aldern in his gripping new book, The Weight of Nature: How a Changing Climate Changes Our Brains. “It is the job of your brain to model the world as it is,” he goes on. “And the world is mutating.”

You may already be familiar with some of his examples — that the heat can make us dumber and more aggressive, and that people who survive traumatic weather events can get post-traumatic stress disorder. But Aldern’s book — which, in spite of its author’s technical background, is immensely readable and literary — pushes far past the familiar, touching on topics as wide-ranging as brain-eating amoebas, language death, and free will. The common theme throughout, though, is that climate is our unseen “puppeteer.”

Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

You use the phrase “the weight of nature” in several contexts throughout the book. It made me think of both Altas, as in “the weight on our shoulders,” and also the idea of determinism that you get into a bit. At what point in the writing process did you come up with the title?

It was early on that the title came to me, but it was not the original title. I’ve been working on this project for six or seven years, and initially my working title was something awful like Nature’s Marionette, which sought to communicate this notion of forcing our hands — the puppetmaster behind our decision-making.

But I wanted to be able to communicate this feeling of being guided by the environment — in addition to carrying said burden — because it felt like weight. It does feel heavy, and heaviness does a lot of things, including forcing our hands.

Is there something about brains that makes them uniquely vulnerable to climate change? I ask because I’m sure books could be written about how climate change hurts our hearts or lungs, too. But it seems to impact our brains in a variety of terrifying forms.

Hearts do one thing: They beat. Brains are always reaching outward, and so, by extension, they’re enmeshed in the same manner in which one can imagine our entire bodies to be enmeshed in this “environment.”

More specifically, in addition to the reaching-out action, brains are actively modeling the world around us. That is what they do. This notion of having an active organ, as opposed to a somewhat passive organ, makes the difference because brains are always integrating new information about the world. And the world is changing.

As we come to terms with this changing world — and when I use the phrase “come to terms,” I’m not seeking to deploy some kind of intellectual or emotional metaphor here. I mean, on a biophysical level, as we’re coming to terms with these changes — then neurochemical changes result accordingly. We respond in kind. Certainly, our other organs are adaptive to various degrees, but the whole point of the brain is its adaptive nature, right? It seeks to model the world around us, and it implements change through a system known as neuroplasticity. It is an organ that is built for modeling and integrating change. And so, is it any wonder that climate change acts directly on this organ in ways it may not act on others?

The chapter about Karl Friston and the give-and-take of perception — in which you write, “our actions are the world’s sensations, and our sensations are the world’s actions” — completely blew my mind.

I haven’t even told this to my editor, but I think if I’m ever granted the privilege of writing a book again, I might try to pitch a biography of Karl Friston. His research is unbelievably interesting.

Is his work well-known among neuroscientists, or is it kind of fringe even within the community?

That’s a fabulous question, and I'll tell you why: Karl is one of the most cited neuroscientists of all time, but most neuroscientists have not heard of him. The reason that paradox is true is because, early in his career, he developed some of the basic algorithmic technology underlying functional resonance in functional magnetic resonance imaging: fMRI. And so, anytime anybody uses fMRI, which most neuroscientists do, there’s this casual Fristonian citation that goes back to his early work.

Far fewer people have paid attention to his groundbreaking work on what’s called the free energy hypothesis. If you Google, like, “the most influential neuroscientists of all time,” he’s always on these lists, but nobody knows who he is. Well, nobody is a stretch; he’s reasonably well-known in sub-communities. But by and large, he’s such an abstract thinker, and his material is so difficult to internalize, that most people who are attracted to his work fall into the neuro-theory community, computational neuroscientists, theoretical neuroscientists — and that’s, frankly, the vast minority of neuroscientists. So he is somewhat of an unknown entity, which is just astounding because he has literally been in the running for the Nobel.

Something that struck me was how many gaps there are in the science of understanding our own brains — we often seem to know the general region where thoughts or impulses originate but not quite the mechanics of how they work. Are there certain mysteries about our consciousness and perception that might always remain slightly out of our reach?

There’s a huge body of research that seeks to address whether or not the question of consciousness, and understanding it, is unravelable at all. This is known as the hard problem of consciousness. Have we made progress in our understanding of consciousness over the past 100 or 200 years? Well, almost certainly, yes. And in neuroscience, we’ve come closer to an understanding of what perception is and what consciousness is.

Will another 20 years or so get us closer to an ultimate, grounded, and internalized rational scientific representation there of? Maybe! But there are also people today who argue with just as much empirical backing that the notion of solving consciousness — the notion of, basically, a self coming to understand itself — is a logically impossible act.

I’m not a consciousness researcher, so I’m not sure if I have enough background to really say that I’ve made my mind up. But there are certainly folks out there who say consciousness is not something that’s solvable, it’s not something that we will ever understand in the same materialistic terms that, perhaps, we understand the heart.

I’m going to be obnoxious and ask the AI question. You didn’t really get into the possibility and pitfalls of technology, but I’m wondering if it was back of mind at all while you were writing?

I’m going to give you an obnoxious answer. In fact, it’s a decades-old obnoxious answer. When I’m thinking about this stuff, my instinct is to think about technology in terms of the manners in which it removes us from nature. So much of the promise in this area of research — and I do think there’s promise, I don’t think it’s all doom and gloom — is that this intimate relationship we have with the planet is also that which can be leveraged to help mediate some of these detrimental effects.

There’s a fabulous book from a couple of years ago, The Nature Fix, by Florence Williams; I have come to understand my book as its dark version. The Nature Fix details all the manners in which interacting with nature, as opposed to the built environment, is essential for mental, psychological, spiritual, and neurological health.

This is an obnoxious answer because it’s the classic “Oh, kids are all looking at their phones!” But I think that’s real — the handheld devices and the omniscience of the all-knowing screen, which, perhaps we can extend that to the LLMs. As it were, there’s this suite of technologies that mediates our relationship both with knowledge writ large and the broader environment outside of ourselves. In my estimate, it filters the world in a way that I suspect is preventing us from interacting with some of the benefits that the environment has to offer.

The same things that make our brains incredible — their ability to adapt, create, and use language — are also what allowed us to invent the combustion engine, organize global commodities markets, and design machines for fracking. In a sense, the climate fight requires beating back against the weight and consequences of our own brains, right?

When I think about this question, it’s less about “how can we ensure we’re using the tools of evolution, the powers of the brain, for good,” and more about coming to terms with the fact that something like free will doesn’t exist.

There’s this thinker, Timothy Morton, who writes a lot about our enmeshment with the environment and the degree to which one cannot separate the self from the greater universe. Taken to its extreme, that thinking — which I think is very powerful — implies that what we need to wrap our heads around and come to terms with is the fact that we’re not really making decisions, per se. It’s just a universe of particles in motion. So grappling with what Morton calls the ecological thought, grappling with this notion of determinism and enmeshment, and trying to suss out the moral responsibilities that fall out of that relationship — that, to me, is a worthy task and, frankly, an unsolved problem.

As a neuroscientist working in the climate space, what keeps you up at night?

The 20-year timeline keeps me up at night. A lot of the research that we’re coming to terms with today is going to make itself known on a much more visceral level over the next 20 to 50 years. If it is in fact the case that cyanobacterial blooms are releasing a neurotoxin that is spurring an increased risk of ALS, that neurodegenerative disease isn’t necessarily going to manifest in people whom it is likely to affect for a number of years. We’re not going to see in tangible, visceral terms a corresponding spike in this disease in the general population for another couple of decades.

I just published a piece in The Guardian about some of these effects, and one of the researchers I interviewed for that piece basically said what I’m trying to communicate now, which is: We’re in the midst of a grand experiment. It’s not like a lab where you’ve got a rat, and you’re selectively exposing it to one toxin over the course of some fixed time period and measuring the results. The lab that we’re in is the Earth and we are exposed to climatic and environmental stressors in this soup, chronically, for years and years, and in unknown quantities. At some point, we’re going to look around and say, “Oh, this is really bad. We should do something about this.” And for many people, it will be too late.

What gives you hope?

I don’t like hope. I think that hope breeds complacency — or, at least, false hope does. I tend personally not to look for vectors of hope per se, which is not to say that I’m a pessimist or a nihilist or anything like that. I look for climate solutions, for example, or sources of resilience, or stories of the capacity of the human spirit that inspire me with a feeling of desire. I’m interested in having images out there in the world that point my compass toward a future that I would like to realize.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

1. Marion County, Indiana — State legislators made a U-turn this week in Indiana.

2. Baldwin County, Alabama — Alabamians are fighting a solar project they say was dropped into their laps without adequate warning.

3. Orleans Parish, Louisiana — The Crescent City has closed its doors to data centers, at least until next year.

A conversation with Emily Pritzkow of Wisconsin Building Trades

This week’s conversation is with Emily Pritzkow, executive director for the Wisconsin Building Trades, which represents over 40,000 workers at 15 unions, including the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, the International Union of Operating Engineers, and the Wisconsin Pipe Trades Association. I wanted to speak with her about the kinds of jobs needed to build and maintain data centers and whether they have a big impact on how communities view a project. Our conversation was edited for length and clarity.

So first of all, how do data centers actually drive employment for your members?

From an infrastructure perspective, these are massive hyperscale projects. They require extensive electrical infrastructure and really sophisticated cooling systems, work that will sustain our building trades workforce for years – and beyond, because as you probably see, these facilities often expand. Within the building trades, we see the most work on these projects. Our electricians and almost every other skilled trade you can think of, they’re on site not only building facilities but maintaining them after the fact.

We also view it through the lens of requiring our skilled trades to be there for ongoing maintenance, system upgrades, and emergency repairs.

What’s the access level for these jobs?

If you have a union signatory employer and you work for them, you will need to complete an apprenticeship to get the skills you need, or it can be through the union directly. It’s folks from all ranges of life, whether they’re just graduating from high school or, well, I was recently talking to an office manager who had a 50-year-old apprentice.

These apprenticeship programs are done at our training centers. They’re funded through contributions from our journey workers and from our signatory contractors. We have programs without taxpayer dollars and use our existing workforce to bring on the next generation.

Where’s the interest in these jobs at the moment? I’m trying to understand the extent to which potential employment benefits are welcomed by communities with data center development.

This is a hot topic right now. And it’s a complicated topic and an issue that’s evolving – technology is evolving. But what we do find is engagement from the trades is a huge benefit to these projects when they come to a community because we are the community. We have operated in Wisconsin for 130 years. Our partnership with our building trades unions is often viewed by local stakeholders as the first step of building trust, frankly; they know that when we’re on a project, it’s their neighbors getting good jobs and their kids being able to perhaps train in their own backyard. And local officials know our track record. We’re accountable to stakeholders.

We are a valuable player when we are engaged and involved in these sting decisions.

When do you get engaged and to what extent?

Everyone operates differently but we often get engaged pretty early on because, obviously, our workforce is necessary to build the project. They need the manpower, they need to talk to us early on about what pipeline we have for the work. We need to talk about build-out expectations and timelines and apprenticeship recruitment, so we’re involved early on. We’ve had notable partnerships, like Microsoft in southeast Wisconsin. They’re now the single largest taxpayer in Racine County. That project is now looking to expand.

When we are involved early on, it really shows what can happen. And there are incredible stories coming out of that job site every day about what that work has meant for our union members.

To what extent are some of these communities taking in the labor piece when it comes to data centers?

I think that’s a challenging question to answer because it varies on the individual person, on what their priority is as a member of a community. What they know, what they prioritize.

Across the board, again, we’re a known entity. We are not an external player; we live in these communities and often have training centers in them. They know the value that comes from our workers and the careers we provide.

I don’t think I’ve seen anyone who says that is a bad thing. But I do think there are other factors people are weighing when they’re considering these projects and they’re incredibly personal.

How do you reckon with the personal nature of this issue, given the employment of your members is also at stake? How do you grapple with that?

Well, look, we respect, over anything else, local decision-making. That’s how this should work.

We’re not here to push through something that is not embraced by communities. We are there to answer questions and good actors and provide information about our workforce, what it can mean. But these are decisions individual communities need to make together.

What sorts of communities are welcoming these projects, from your perspective?

That’s another challenging question because I think we only have a few to go off of here.

I would say more information earlier on the better. That’s true in any case, but especially with this. For us, when we go about our day-to-day activities, that is how our most successful projects work. Good communication. Time to think things through. It is very early days, so we have some great success stories we can point to but definitely more to come.

The number of data centers opposed in Republican-voting areas has risen 330% over the past six months.

It’s probably an exaggeration to say that there are more alligators than people in Colleton County, South Carolina, but it’s close. A rural swath of the Lowcountry that went for Trump by almost 20%, the “alligator alley” is nearly 10% coastal marshes and wetlands, and is home to one of the largest undeveloped watersheds in the nation. Only 38,600 people — about the population of New York’s Kew Gardens neighborhood — call the county home.

Colleton County could soon have a new landmark, though: South Carolina’s first gigawatt data center project, proposed by Eagle Rock Partners.

That’s if it overcomes mounting local opposition, however. Although the White House has drummed up data centers as the key to beating China in the race for AI dominance, Heatmap Pro data indicate that a backlash is growing from deep within President Donald Trump’s strongholds in rural America.

According to Heatmap Pro data, there are 129 embattled data centers located in Republican-voting areas. The vast majority of these counties are rural; just six occurred in counties with more than 1,000 people per square mile. That’s compared with 93 projects opposed in Democratic areas, which are much more evenly distributed across rural and more urban areas.

Most of this opposition is fairly recent. Six months ago, only 28 data centers proposed in low-density, Trump-friendly countries faced community opposition. In the past six months, that number has jumped by 95 projects. Heatmap’s data “shows there is a split, especially if you look at where data centers have been opposed over the past six months or so,” says Charlie Clynes, a data analyst with Heatmap Pro. “Most of the data centers facing new fights are in Republican places that are relatively sparsely populated, and so you’re seeing more conflict there than in Democratic areas, especially in Democratic areas that are sparsely populated.”

All in all, the number of data centers that have faced opposition in Republican areas has risen 330% over the past six months.

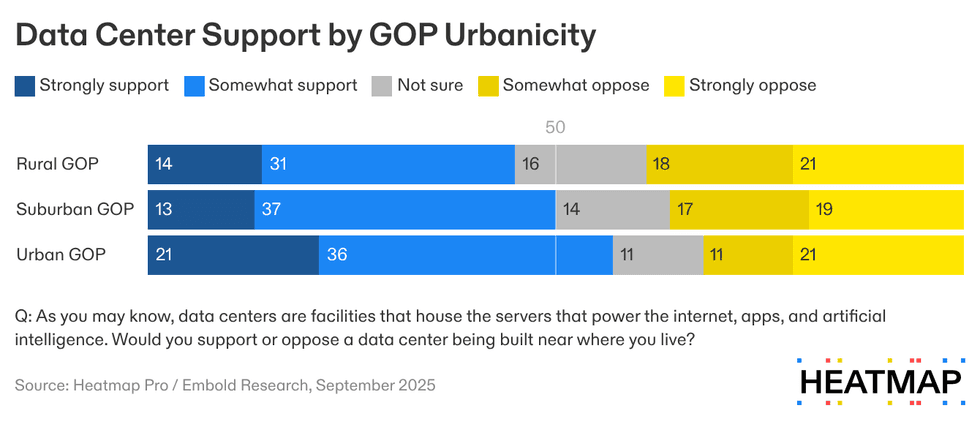

Our polling reflects the breakdown in the GOP: Rural Republicans exhibit greater resistance to hypothetical data center projects in their communities than urban Republicans: only 45% of GOP voters in rural areas support data centers being built nearby, compared with nearly 60% of urban Republicans.

Such a pattern recently played out in Livingston County, Michigan, a farming area that went 61% for President Donald Trump, and “is known for being friendly to businesses.” Like Colleton County, the Michigan county has low population density; last fall, hundreds of the residents of Howell Township attended public meetings to oppose Meta’s proposed 1,000-acre, $1 billion AI training data center in their community. Ultimately, the uprising was successful, and the developer withdrew the Livingston County project.

Across the five case studies I looked at today for The Fight — in addition to Colleton and Livingston Counties, Carson County, Texas; Tucker County, West Virginia; and Columbia County, Georgia, are three other red, rural examples of communities that opposed data centers, albeit without success — opposition tended to be rooted in concerns about water consumption, noise pollution, and environmental degradation. Returning to South Carolina for a moment: One of the two Colleton residents suing the county for its data center-friendly zoning ordinance wrote in a press release that he is doing so because “we cannot allow” a data center “to threaten our star-filled night skies, natural quiet, and enjoyment of landscapes with light, water, and noise pollution.” (In general, our polling has found that people who strongly oppose clean energy are also most likely to oppose data centers.)

Rural Republicans’ recent turn on data centers is significant. Of 222 data centers that have faced or are currently facing opposition, the majority — 55% —are located in red low-population-density areas. Developers take note: Contrary to their sleepy outside appearances, counties like South Carolina’s alligator alley clearly have teeth.