You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

The Florida insurance market took another hit this week when Farmers announced it would pull out of the state, leaving around 100,000 customers unable to renew their policies.

While the news garnered headlines, it was exceptional not so much for Farmers pulling out, but for how long the insurance giant had stayed in the Florida market. Other national carriers had long since left and remaining Florida-specific carriers have been suffering under the weight of the state’s dangerous weather and uniquely lawsuit friendly legal environment.

At the same time that Farmers announced its departure, records were being set for ocean temperature in Florida, crossing 90 degrees in the waters off the southern part of the state. And the state may be in for nasty storms later this year. Forecasters at Colorado State University last week projected an “above-average” Atlantic hurricane season .

Farmers’ departure from Florida is also just the latest example of a major national carrier leaving a large, disaster-prone state. Allstate and State Farm said earlier this year they were leaving the California property market.

Farmers “looked at their book and determined they needed to reduce their catastrophe exposure. Most national carriers made that decision a long time ago,” RJ Lehmann, editor-in-chief and senior fellow at the International Center for Law and Economics, told me.

Customers with Farmers-branded home, auto, or umbrella insurance will not be able to renew their policy as their terms expires. The changes will not begin to take effect for 90 days.

“This business decision was necessary to effectively manage risk exposure,” Farmers spokesperson Trevor Chapman said in a statement. The company will continue to offer insurance through other brands it owns, Bristol West and Foremost.

The future of Florida’s insurance industry could be a harbinger for the rest of the country as it deals with extreme weather exacerbated by rising temperatures. Florida is a tough insurance market for the obvious reasons — property damage caused by wind, rain, and flooding from tropical storms (not to mention wildfires and tornadoes) — as well as its unique (although changing) legal environment.

While more and more of Florida’s insurance business is being taken on by the state-run Citizens Property Insurance Corporation, some followers of the state's economy are cautiously optimistic that insurers could eventually return to the state. But that return would likely be conditioned on a market and legal environment far more friendly to insurance companies, one with high premium and reduced rights for policyholders. After all, Florida’s high insurance rates have hardly stopped people from moving in, but the combination of extreme weather and high homeowner insurance rates could put the Florida dream of home ownership in America’s tropical climate out of reach for many.

The legal environment is changing thanks to reforms of Florida’s uniquely insurance company-unfriendly litigation system that have been signed by Governor Ron DeSantis over the past few years. This included eliminating Florida’s distinctive “one-way” attorney fees set-up, whereby if a policyholder won any amount of money from an insurer, the insurance company would pay attorneys fees for both sides. This system was obviously disliked by insurance companies, who argued that it led to the flowering of a Florida-specific cottage industry for trial attorneys; while those attorneys argued it gave policyholders a shot in prevailing against well-funded insurance companies.

Another bill banned the practice of letting policyholders “assign” the right to pursue a claim — and sue insurers — to contractors, another practice blamed by the industry for increased litigation.

Florida had over 75 percent of homeowners’ lawsuits in the country as a whole, despite only having 7 percent of the homeowners’ insurance claims, according to data from the Florida Office of Insurance Regulation.

Jeff Brandes, a former Republican state legislator who has long advocated to litigation reforms, predicted that the legislation, which was passed in April, will take somewhere between 18 and 24 months to have an effect on the market.

“I fully expect three-five companies to pull out and rates to go up 10 to 15 percent next year,” Brandes said, although he noted that he expected rates to stabilize in 2025.

In February, the St. Petersburg-based United Property & Casualty Insurance Company was deemed insolvent by state regulators. Some 15 insurers became insolvent between 2020 and the end of 2022.

Since 2016, Florida property insurance companies have been losing money on their underwriting — premiums collected minus claims paid — and only in the first quarter of this year did the industry as a whole turn a net profit, and that was thanks to investment earnings; underwriting profit was still negative.

Even if insurers return to the state, that doesn’t mean that said insurance will necessarily be attractive to homeowners: Part of why a less litigation-friendly market may be tempting to insurers is the very high rates that Florida policyholders pay for home insurance.

Average premiums in the state range from $1,651 in Sumter County in Central Florida to as high as $5,665 in Miami-Dade or $5,710 in Palm Beach, according to the Florida Office of Insurance Regulation. The nationwide average is around $1,900.

“We’re getting to a place where the availability problem will get better,” Lehmann said. “The affordability problem? We live on a low-lying peninsula with some of the most hurricane prone waters in the world.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Topsy turvy oil prices aren’t great for the U.S.

Oil prices are all over the place as markets reopened this week, climbing as high as $120 a barrel before crashing to around $85 after Donald Trump told CBS News that the war with Iran “is very complete, pretty much,” and that he was “thinking about taking it over,” referring to the Strait of Hormuz, the artery through which about a third of the world’s traded oil flows.

Even $85 is substantially higher than the $57 per barrel price from the end of last year. At that point, forecasters from both the public and the private sectors were expecting oil to stick around $60 a barrel through 2026.

Of course, crude oil itself is not something any consumer buys — but those high prices would likely feed through to higher consumer prices throughout the U.S. economy. That includes the price of gasoline, of course, which has risen by about $0.50 a gallon in the past month, according to AAA, — and jet fuel, which will mean increased travel costs. “Book your airfares now if they haven’t moved already,” Skanda Amarnath, the executive director of the economic policy think tank Employ America, told me.

High oil prices also raise the price of goods and services not directly linked to oil prices — groceries, for instance. “The cost of food, especially at the grocery store, is a function of the cost of diesel,” which fuels the trucks that get food to shelves, Amarnath told me. Diesel prices have risen even more than gasoline in the past week, by over $0.85 a gallon.

“We’ll see how long these prices stay elevated, how they feed their way through the supply chain and the value chain. But it’s clearly the case that it is a pretty adverse situation for both businesses and consumers.”

The oil market is going through one of the largest physical shocks in its modern history. Bloomberg’s Javier Blas estimates that of the 15 million barrels per day that regularly flow through the Strait of Hormuz, only about a third is getting through to the global market, whether through the strait itself or by alternative routes, such as the pipeline from Saudi Arabia’s eastern oil fields to the Red Sea.

Global daily oil production is just above 100 million barrels per day, meaning that around 10% of the oil supply on the market is stuck behind an effective blockade.

“The world is suddenly ‘short’ a volume that, in normal times, would dwarf almost any supply/demand imbalance we debate,” Morgan Stanley oil analyst Martjin Rats wrote in a note to clients on Sunday.

The fact that the U.S. is itself a leading producer and exporter of oil will only provide so much relief. Private sector economists have estimated that every $10 increase in the price of oil reduces economic growth somewhere between 0.1 and 0.2 percentage points.

“Petroleum product prices here in the U.S. tend to reflect global market conditions, so the price at the pump for gasoline and diesel reflect what’s going on with global prices,” Ben Cahill, a senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told me. “What happens in the rest of the world still has a deep impact on U.S. energy prices.”

To the extent the U.S. economy benefits from its export capacity, the effects are likely localized to areas where oil production and export takes place, such as Texas and Louisiana. For the economy as a whole, higher oil prices will improve the “terms of trade,” essentially a measure of the value of imports a certain quantity of exports can “buy,” Ryan Cummings, chief of staff at Stanford Institute for Economic Policymaking, told me.

Could the U.S. oil industry ramp up production to capture those high prices and induce some relief?

Oil industry analysts, Heatmap founding executive editor Robinson Meyer, and the TV show Landman have all theorized that there is a “goldilocks” range of oil prices that are high enough to encourage exploration and production but not so high as to take out the economy as a whole. This range starts at around $60 or $70 on the low end and tops out at around $90 or $95. Above that, the economic damage from high prices would likely outweigh any benefit to drillers from expanded production.

And that’s if production were to expand at all.

“Capital discipline” has been the watchword of the U.S. oil and gas industry for years since the shale boom, meaning drillers are unlikely to chase price spikes by ramping up production heedlessly, CSIS’ Ben Cahill told me. “I think they’ll be quite cautious about doing that,” he said.

A test drive provided tantalizing evidence that a great, cheap EV is possible for the U.S.

Midway through the tortuous test drive over the mountains to Malibu, as the new Chevrolet Bolt EV ably zipped through a series of sharp canyon corners, I couldn’t help but think: Who would want to kill this car?

Such is life for the Bolt. Chevy revived the budget electric car after its fans howled when it killed the first version in 2023. But by the time the car press assembled last week for the official test drive of Bolt 2.0, the new car already had an expiration date: General Motors said it would end the production run next summer. This is a shame for a variety of reasons. Among the most important: The new Bolt, which starts just under $30,000 and is soon to start arriving at Chevy dealerships, shows that the cheap EV for the masses is really, almost there.

The 2027 Bolt comes with a 65 kilowatt-hour lithium iron phosphate battery that’s rated to deliver 262 miles of range. That’s not bad for an economy car, given that lots of more expensive EVs came with ranges in the low 200s just a couple of years ago.

Charging speed, the big bugaboo with the original Bolt, is fixed. The glacial 50-kilowatt speed has risen to 150 kilowatts, allowing the car to charge from 10% to 80% in about 25 minutes. That pales in comparison to the 350-kilowatt Hyundai touts for some of its EVs, but it makes the Bolt road trip an acceptable experience, not a slog. Crucially, the new Bolt comes with the NACS port and will seamlessly plug-and-charge at many charging stations, including Tesla’s.

Bolt comes with a single motor that delivers 210 horsepower and 169 pound-feet of torque — not eye-popping numbers. But because all of an electric car’s torque is available at any time, the Bolt feels livelier as it accelerates away from a start compared to an equivalent combustion-powered economy car. It huffs and puffs just a tad trying to accelerate uphill on California’s mountain highways, sure, but Bolt has enough oomph to have some fun without getting you into trouble. And in a world of white cars, Bolt comes in honest-to-goodness colors. Red. Blue. Yellow!

The tech features are the same story — that is, plenty good for the price. Many Bolt loyalists are incensed that Chevy killed off Apple Carplay and Android Auto integration in the new car, forcing drivers to rely on what’s built in. For those who can get over the disappointment, what is built into Bolt’s 11-inch touchscreen is pretty good, starting with Google Maps integration for navigation. Its method for displaying charging stations — and allowing the driver to filter them by plug style, provider, and other factors — isn’t quite up to the Silicon Valley seamlessness of a Rivian, but is easier to use than what a lot of legacy car companies put in their EVs. (The fabulous Kia EV9 three-row SUV I tested just before the Bolt is superior in just about every way except this.)

The Bolt even has a few features you wouldn’t expect at the entry level. The surround vision recorder for storing footage from the car’s camera is a first for a GM vehicle, Chevy says. The brand is also making a big to-do over the Super Cruise hands-free driving feature since the Bolt is now the least expensive car to get it, though adding all that tech takes the basic LT version of the Bolt up from $29,000 to more than $35,000, which is the starting price for the bigger Chevy Equinox EV.

With so much going right for this vehicle, why preemptively kill it? The most obvious factor is the Trump White House. Chevrolet had always called the Bolt’s return a limited run, but the fact that its production run might last for just a year and a half is a direct result of Trump tariffs: GM wants to make gas-powered Buick crossovers, currently made in China, at the Kansas factory that builds the Bolt.

And the loss last year of the federal incentive to buy an EV is particularly punitive for the Bolt. With $7,500 shaved off the price, the Chevy EV would have been cost-competitive with the cheapest new gas cars, like the Hyundai Elantra or Toyota Corolla. Without it, Bolt is closer in price to a larger vehicle like the Toyota RAV4. When Chevy can’t make the case that its EV is as cheap as any other small car you might be looking at, it must sell a car like Bolt on its down-the-road value: very little routine maintenance, no buying gasoline during a period of wartime oil shocks, and so on. That’s a tougher task, and perhaps explains why GM was so quick to move on.

Still, there’s clearly something bigger at stake here for GM. The American car companies’ pivot back to the short-term profitability of petroleum, exemplified by the Bolt-Buick affair, comes as the rest of the world continues to embrace EVs. Headlines lately have wondered whether China’s ascent combined with America’s yoyo-ing on electric power could lead to Detroit’s outright demise, leaving the U.S. auto industry with scraps as someone else’s superior EVs take over the world.

In this light, Chevy’s own market data on Bolt is especially jarring. Of the nearly 200,000 Bolts on the road from the car’s previous generation, 75% percent of those drivers came from other car companies to GM, and 72% remained loyal to GM. In other words, the new Bolt is set to build on General Motors’ status as the top EV-seller in America behind Tesla by expanding the established base of customers who love Chevy electric cars. That is what’s being tossed aside to increase quarterly profits.

Maybe the Bolt will surprise its maker, again. Even if a groundswell of enthusiasm for the new car isn’t enough to save it from extinction, perhaps it will prove to GM to give the budget EV yet another go-around when the market shifts yet again.

Current conditions: Spring-like temperatures have arrived in New York City, with a high of 62 degrees Fahrenheit today • The death toll from the flooding in Nairobi, Kenya, has risen to at least 42 • Heavy rain in Peru threatens landslides amid what’s already been a deadly wet season.

It only took a week. But, as I told you might happen sooner than later, oil prices surged past $100 per barrel for the first time since 2022 as the war against Iran continues. The latest hit to the global market came when Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates started cutting production over the weekend at key oil fields as shipments through the Strait of Hormuz ground to a halt. In a post on his Truth Social network, President Donald Trump said prices “will drop rapidly when the destruction of the Iran nuclear threat is over,” calling the rise “a very small price to pay for U.S.A.” In response, oil analyst Rory Johnston said Trump’s statement would only spur on the market craziness. “No one who has any idea how the oil market works is buying it — all this does is make it seem like Trump believes it, which means the base case length of this disruption is growing ever-longer,” he wrote. “Tick. Tock.”

The war’s effect on energy markets isn’t just an oil story. As Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote, it’s also a natural gas story. Similarly, as Matthew wrote last week, the winners of the market chaos run the gamut from coal to solar panels.

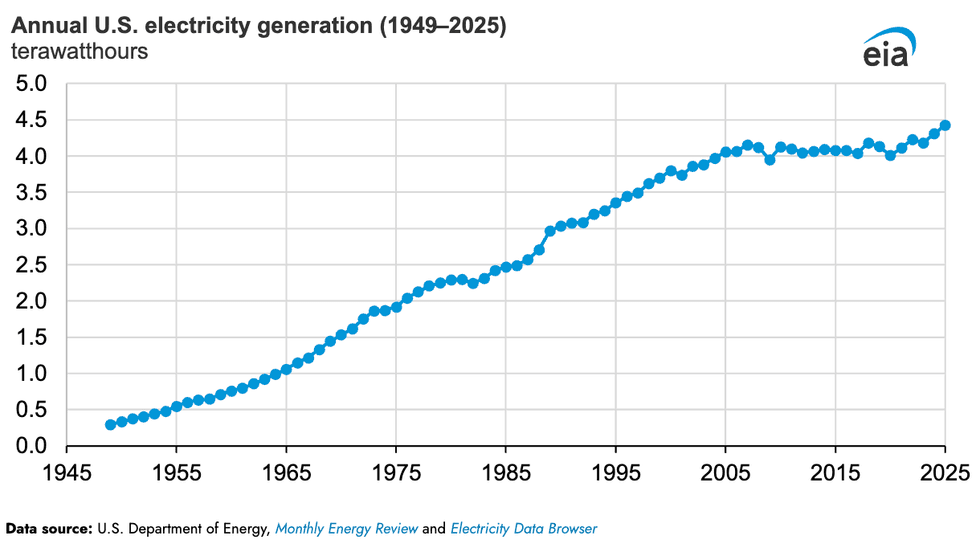

The numbers are in. Last year, the United States generated 4,430 terawatt-hours of electricity. That’s up 2.8% from 2024, which previously had been the highest annual total in the Energy Information Administration’s record books, which date back to 1949. Residential electricity sales grew 2.2%, while commercial surged by 2.9% and industrial rose by just 0.7%.

France produced a record 521.1 terawatt-hours of low-carbon electricity in 2025 as upgrades to existing nuclear reactors allowed the fleet to produce more power, according to data from the grid operator RTE. The latest report is not yet public on RTE’s website, but NucNet reviewed the findings. The electricity mix has largely remained steady for the last two years. France first achieved a 95% low-carbon grid back in 2024, RTE data shows.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

Qcells has resumed solar panel assembly at its plant in Cartersville, Georgia, following a series of delays. By the end of this year, the South Korean-owned company said it plans to add the capacity to pump out 3.3 gigawatts of ingots, wafers, and cells per year. “We are proud to be back to work manufacturing the American-made energy the country needs right now,” Marta Stoepker, head of communications at Qcells, said in a statement. “Like any company, hurdles have and will occur, which requires us to adapt and be nimble, but our overall goal remains the same — to build a complete American solar supply chain.” The moves comes as MAGA warms to solar power as part of a broader “renewables thaw” that Heatmap’s Jael Holzman reported is part of a legal strategy.

Roughly two hours away, SK Battery America laid off nearly 1,000 workers at its factory northeast of Atlanta as automakers cool on electric vehicles. Friday marked the last working day for 958 employees, according to a federal filing the Associated Press reviewed.

A wave energy startup hoping to harness one of the trickier sources of renewable power just broke a record with its latest pilot project. Last month, Eco Wave Power deployed its EWP-EDF One technology Jaffa Port in Israel. The pilot test lasted nine days last month under moderate conditions with daily average wave heights between one and two meters. Throughout the test, the project generated about 2,000 kilowatthours of electricity. “Not only did we continue stable production during moderate wave conditions, but we also experienced the highest waves recorded at our site to date,” Inna Braverman, Eco Wave Power’s chief executive, said in a statement to the trade publication Offshore Energy. “Achieving record average and peak power production during 3-meter wave events provides meaningful validation of our technology’s performance potential as we scale toward commercial projects.”

Scientists discovered a molecular trick used by a unique group of plants to convert sunlight into food. Hornworts are the only known land plant that possesses internal compartments that concentrate carbon dioxide similarly to algae. A new study by researchers at the Boyce Thompson Institute, Cornell University, and the University of Edinburgh suggests that genes from the plants could be used to breed more resistant crops such as wheat. “This research shows that nature has already tested solutions we can learn from,” said Fay-Wei Li, a co-author of the study, said in a statement. “Our job is to understand those solutions well enough to apply them where they're needed most — in the crops that feed the world.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct the added manufacturing capacity at Qcells’ Cartersville plant.