You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

If it turns out to be a bubble, billions of dollars of energy assets will be on the line.

The data center investment boom has already transformed the American economy. It is now poised to transform the American energy system.

Hyperscalers — including tech giants such as Microsoft and Meta, as well as leaders in artificial intelligence like OpenAI and CoreWeave — are investing eyewatering amounts of capital into developing new energy resources to feed their power-hungry data infrastructure. Those data centers are already straining the existing energy grid, prompting widespread political anxiety over an energy supply crisis and a ratepayer affordability shock. Nothing in recent memory has thrown policymakers’ decades-long underinvestment in the health of our energy grid into such stark relief. The commercial potential of next-generation energy technologies such as advanced nuclear, batteries, and grid-enhancing applications now hinge on the speed and scale of the AI buildout.

But what happens if the AI boom buffers and data center investment collapses? It is not idle speculation to say that the AI boom rests on unstable financial foundations. Worse, however, is the fact that as of this year, the tech sector’s breakneck investment into data centers is the only tailwind to U.S. economic growth. If there is a market correction, there is no other growth sector that could pick up the slack.

Not only would a sudden reversal in investor sentiment make stranded assets of the data centers themselves, which will lose value as their lease revenue disappears, it also threatens to strand all the energy projects and efficiency innovations that data center demand might have called forth.

If the AI boom does not deliver, we need a backup plan for energy policy.

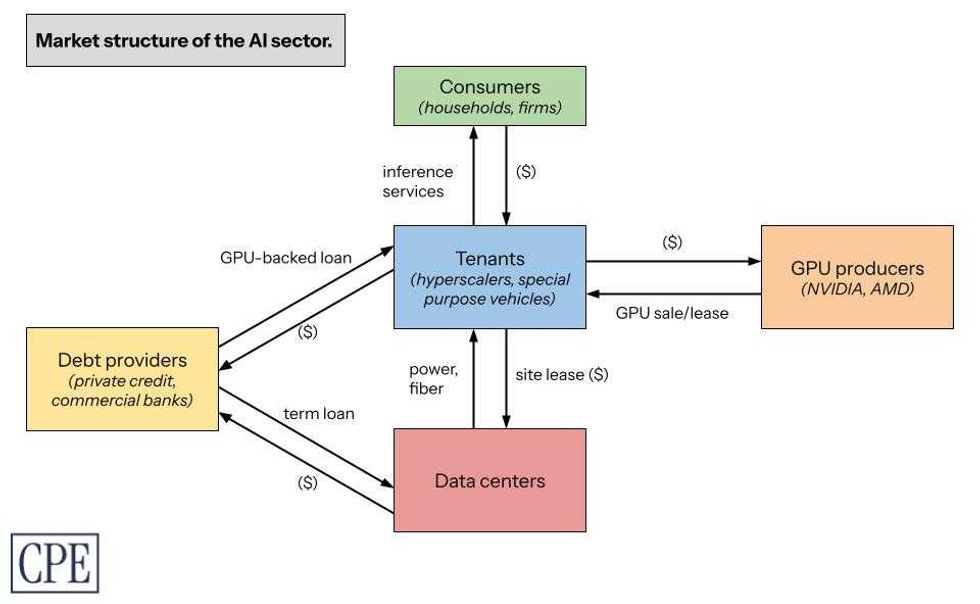

An analysis of the capital structure of the AI boom suggests that policymakers should be more concerned about the financial fundamentals of data centers and their tenants — the tech companies that are buoying the economy. My recent report for the Center for Public Enterprise, Bubble or Nothing, maps out how the various market actors in the AI sector interact, connecting the market structure of the AI inference sector to the economics of Nvidia’s graphics processing units, the chips known as GPUs that power AI software, to the data center real estate debt market. Spelling out the core financial relationships illuminates where the vulnerabilities lie.

First and foremost: The business model remains unprofitable. The leading AI companies ― mostly the leading tech companies, as well as some AI-specific firms such as OpenAI and Anthropic ― are all competing with each other to dominate the market for AI inference services such as large language models. None of them is returning a profit on its investments. Back-of-the-envelope math suggests that Meta, Google, Microsoft, and Amazon invested over $560 billion into AI technology and data centers through 2024 and 2025, and have reported revenues of just $35 billion.

To be sure, many new technology companies remain unprofitable for years ― including now-ubiquitous firms like Uber and Amazon. Profits are not the AI sector’s immediate goal; the sector’s high valuations reflect investors’ assumptions about future earnings potential. But while the losses pile up, the market leaders are all vying to maximize the market share of their virtually identical services ― a prisoner’s dilemma of sorts that forces down prices even as the cost of providing inference services continues to rise. Rising costs, suppressed revenues, and fuzzy measurements of real user demand are, when combined, a toxic cocktail and a reflection of the sector’s inherent uncertainty.

Second: AI companies have a capital investment problem. These are not pure software companies; to provide their inference services, AI companies must all invest in or find ways to access GPUs. In mature industries, capital assets have predictable valuations that their owners can borrow against and use as collateral to invest further in their businesses. Not here: The market value of a GPU is incredibly uncertain and, at least currently, remains suppressed due to the sector’s competitive market structure, the physical deterioration of GPUs at high utilization rates, the unclear trajectory of demand, and the value destruction that comes from Nvidia’s now-yearly release of new high-end GPU models.

The tech industry’s rush to invest in new GPUs means existing GPUs lose market value much faster. Some companies, particularly the vulnerable and debt-saddled “neocloud” companies that buy GPUs to rent their compute capacity to retail and hyperscaler consumers, are taking out tens of billions of dollars of loans to buy new GPUs backed by the value of their older GPU stock; the danger of this strategy is obvious. Others including OpenAI and xAI, having realized that GPUs are not safe to hold on one’s balance sheet, are instead renting them from Oracle and Nvidia, respectively.

To paper over the valuation uncertainty of the GPUs they do own, all the hyperscalers have changed their accounting standards for GPU valuations over the past few years to minimize their annual reported depreciation expenses. Some financial analysts don’t buy it: Last year, Barclays analysts judged GPU depreciation as risky enough to merit marking down the earnings estimates of Google (in this case its parent company, Alphabet), Microsoft, and Meta as much as 10%, arguing that consensus modeling was severely underestimating the earnings write-offs required.

Under these market dynamics, the booming demand for high-end chips looks less like a reflection of healthy growth for the tech sector and more like a scramble for high-value collateral to maintain market position among a set of firms with limited product differentiation. If high demand projections for AI technologies come true, collateral ostensibly depreciates at a manageable pace as older GPUs retain their marketable value over their useful life — but otherwise, this combination of structurally compressed profits and rapidly depreciating collateral is evidence of a snake eating its own tail.

All of these hyperscalers are tenants within data centers. Their lack of cash flow or good collateral should have their landlords worried about “tenant churn,” given the risk that many data center tenants will have to undertake multiple cycles of expensive capital expenditure on GPUs and network infrastructure within a single lease term. Data center developers take out construction (or “mini-perm”) loans of four to six years and refinance them into longer-term permanent loans, which can then be packaged into asset-backed and commercial mortgage-backed securities to sell to a wider pool of institutional investors and banks. The threat of broken leases and tenant vacancies threatens the long-term solvency of the leading data center developers ― companies like Equinix and Digital Realty ― as well as the livelihoods of the construction contractors and electricians they hire to build their facilities and manage their energy resources.

Much ink has already been spilled on how the hyperscalers are “roundabouting” each other, or engaging in circular financing: They are making billions of dollars of long-term purchase commitments, equity investments, and project co-development agreements with one another. OpenAI, Oracle, CoreWeave, and Nvidia are at the center of this web. Nvidia has invested $100 billion in OpenAI, to be repaid over time through OpenAI’s lease of Nvidia GPUs. Oracle is spending $40 billion on Nvidia GPUs to power a data center it has leased for 15 years to support OpenAI, for which OpenAI is paying Oracle $300 billion over the next five years. OpenAI is paying CoreWeave over the next five years to rent its Nvidia GPUs; the contract is valued at $11.9 billion, and OpenAI has committed to spending at least $4 billion through April 2029. OpenAI already has a $350 million equity stake in CoreWeave. Nvidia has committed to buying CoreWeave’s unsold cloud computing capacity by 2032 for $6.3 billion, after it already took a 7% stake in CoreWeave when the latter went public. If you’re feeling dizzy, count yourself lucky: These deals represent only a fraction of the available examples of circular financing.

These companies are all betting on each others’ growth; their growth projections and purchase commitments are all dependent on their peers’ growth projections and purchase commitments. Optimistically, this roundabouting represents a kind of “risk mutualism,” which, at least for now, ends up supporting greater capital expenditures. Pessimistically, roundabouting is a way for these companies to pay each other for goods and services in any way except cash — shares, warrants, purchase commitments, token reservations, backstop commitments, and accounts receivable, but not U.S. dollars. The second any one of these companies decides it wants cash rather than a commitment is when the music stops. Chances are, that company needs cash to pay a commitment of its own, likely involving a lender.

Lenders are the final piece of the puzzle. Contrary to the notion that cash-rich hyperscalers can finance their own data center buildout, there has been a record volume of debt issuance this year from companies such as Oracle and CoreWeave, as well as private credit giants like Blue Owl and Apollo, which are lending into the boom. The debt may not go directly onto hyperscalers’ balance sheets, but their purchase commitments are the collateral against which data center developers, neocloud companies like CoreWeave, and private credit firms raise capital. While debt is not inherently something to shy away from ― it’s how infrastructure gets built ― it’s worth raising eyebrows at the role private credit firms are playing at the center of this revenue-free investment boom. They are exposed to GPU financing and to data center financing, although not the GPU producers themselves. They have capped upside and unlimited downside. If they stop lending, the rest of the sector’s risks look a lot more risky.

A market correction starts when any one of the AI companies can’t scrounge up the cash to meet its liabilities and can no longer keep borrowing money to delay paying for its leases and its debts. A sudden stop in lending to any of these companies would be a big deal ― it would force AI companies to sell their assets, particularly GPUs, into a potentially adverse market in order to meet refinancing deadlines. A fire sale of GPUs hurts not just the long-term earnings potential of the AI companies themselves, but also producers such as Nvidia and AMD, since even they would be selling their GPUs into a soft market.

For the tech industry, the likely outcome of a market correction is consolidation. Any widespread defaults among AI-related businesses and special purpose vehicles will leave capital assets like GPUs and energy technologies like supercapacitors stranded, losing their market value in the absence of demand ― the perfect targets for a rollup. Indeed, it stands to reason that the tech giants’ dominance over the cloud and web services sectors, not to mention advertising, will allow them to continue leading the market. They can regain monopolistic control over the remaining consumer demand in the AI services sector; their access to more certain cash flows eases their leverage constraints over the longer term as the economy recovers.

A market correction, then, is hardly the end of the tech industry ― but it still leaves a lot of data center investments stranded. What does that mean for the energy buildout that data centers are directly and indirectly financing?

A market correction would likely compel vertically integrated utilities to cancel plans to develop new combined-cycle gas turbines and expensive clean firm resources such as nuclear energy. Developers on wholesale markets have it worse: It’s not clear how new and expensive firm resources compete if demand shrinks. Grid managers would have to call up more expensive units less frequently. Doing so would constrain the revenue-generating potential of those generators relative to the resources that can meet marginal load more cheaply — namely solar, storage, peaker gas, and demand-response systems. Combined-cycle gas turbines co-located with data centers might be stranded; at the very least, they wouldn’t be used very often. (Peaker gas plants, used to manage load fluctuation, might still get built over the medium term.) And the flight to quality and flexibility would consign coal power back to its own ash heaps. Ultimately, a market correction does not change the broader trend toward electrification.

A market correction that stabilizes the data center investment trajectory would make it easier for utilities to conduct integrated resource planning. But it would not necessarily simplify grid planners’ ability to plan their interconnection queues — phantom projects dropping out of the queue requires grid planners to redo all their studies. Regardless of the health of the investment boom, we still need to reform our grid interconnection processes.

The biggest risk is that ratepayers will be on the hook for assets that sit underutilized in the absence of tech companies’ large load requirements, especially those served by utilities that might be building power in advance of committed contracts with large load customers like data center developers. The energy assets they build might remain useful for grid stability and could still participate in capacity markets. But generation assets built close to data center sites to serve those sites cheaply might not be able to provision the broader energy grid cost-efficiently due to higher grid transport costs incurred when serving more distant sources of load.

These energy projects need not be albatrosses.

Many of these data centers being planned are in the process of securing permits and grid interconnection rights. Those interconnection rights are scarce and valuable; if a data center gets stranded, policymakers should consider purchasing those rights and incentivizing new businesses or manufacturing industries to build on that land and take advantage of those rights. Doing so would provide offtake for nearby energy assets and avoid displacing their costs onto other ratepayers. That being said, new users of that land may not be able to pay anywhere near as much as hyperscalers could for interconnection or for power. Policymakers seeking to capture value from stranded interconnection points must ensure that new projects pencil out at a lower price point.

Policymakers should also consider backstopping the development of critical and innovative energy projects and the firms contracted to build them. I mean this in the most expansive way possible: Policymakers should not just backstop the completion of the solar and storage assets built to serve new load, but also provide exigent purchase guarantees to the firms that are prototyping the flow batteries, supercapacitors, cooling systems, and uninterruptible power systems that data center developers are increasingly interested in. Without these interventions, a market correction would otherwise destroy the value of many of those projects and the earnings potential of their developers, to say nothing of arresting progress on incredibly promising and commercializable technologies.

Policymakers can capture long-term value for the taxpayer by making investments in these distressed projects and developers. This is already what the New York Power Authority has done by taking ownership and backstopping the development of over 7 gigawatts of energy projects ― most of which were at risk of being abandoned by a private sponsor.

The market might not immediately welcome risky bets like these. It is unclear, for instance, what industries could use the interconnection or energy provided to a stranded gigawatt-scale data center. Some of the more promising options ― take aluminum or green steel ― do not have a viable domestic market. Policy uncertainty, tariffs, and tax credit changes in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act have all suppressed the growth of clean manufacturing and metals refining industries like these. The rest of the economy is also deteriorating. The fact that the data center boom is threatened by, at its core, a lack of consumer demand and the resulting unstable investment pathways is itself an ironic miniature of the U.S. economy as a whole.

As analysts at Employ America put it, “The losses in a [tech sector] bust will simply be too large and swift to be neatly offset by an imminent and symmetric boom elsewhere. Even as housing and consumer durables ultimately did well following the bust of the 90s tech boom, there was a one- to two-year lag, as it took time for long-term rates to fall and investors to shift their focus.” This is the issue with having only one growth sector in the economy. And without a more holistic industrial policy, we cannot spur any others.

Questions like these ― questions about what comes next ― suggest that the messy details of data center project finance should not be the sole purview of investors. After all, our exposure to the sector only grows more concentrated by the day. More precisely mapping out how capital flows through the sector should help financial policymakers and industrial policy thinkers understand the risks of a market correction. Political leaders should be prepared to tackle the downside distributional challenges raised by the instability of this data center boom ― challenges to consumer wealth, public budgets, and our energy system.

This sparkling sector is no replacement for industrial policy and macroeconomic investment conditions that create broad-based sources of demand growth and prosperity. But in their absence, policymakers can still treat the challenge of a market correction as an opportunity to think ahead about the nation’s industrial future.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Europeans have been “snow farming” for ages. Now the U.S. is finally starting to catch on.

February 2015 was the snowiest month in Boston’s history. Over 28 days, the city received a debilitating 64.8 inches of snow; plows ran around the clock, eventually covering a distance equivalent to “almost 12 trips around the Equator.” Much of that plowed snow ended up in the city’s Seaport District, piled into a massive 75-foot-tall mountain that didn’t melt until July.

The Seaport District slush pile was one of 11 such “snow farms” established around Boston that winter, a cutesy term for a place that is essentially a dumpsite for snow plows. But though Bostonians reviled the pile — “Our nightmare is finally over!” the Massachusetts governor tweeted once it melted, an event that occasioned multiple headlines — the science behind snow farming might be the key to the continuation of the Winter Olympics in a warming world.

The number of cities capable of hosting the Winter Games is shrinking due to climate change. Of 93 currently viable host locations, only 52 will still have reliable winter conditions by the 2050s, researchers found back in 2024. In fact, over the 70 years since Cortina d’Ampezzo first hosted the Olympic Games in 1956, February temperatures in the Dolomites have warmed by 6.4 degrees Fahrenheit, according to Climate Central, a nonprofit climate research and communications group. Italian organizers are expected to produce more than 3 million cubic yards of artificial snow this year to make up for Mother Nature’s shortfall.

But just a few miles down the road from Bormio — the Olympic venue for the men’s Alpine skiing events as well as the debut of ski mountaineering next week — is the satellite venue of Santa Caterina di Valfurva, which hasn’t struggled nearly as much this year when it comes to usable snow. That’s because it is one of several European ski areas that have begun using snow farming to their advantage.

Like Ruka in Finland and Saas-Fee in Switzerland, Santa Caterina plows its snow each spring into what is essentially a more intentional version of the Great Boston Snow Pile. Using patented tarps and siding created by a Finnish company called Snow Secure, the facilities cover the snow … and then wait. As spring turns to summer, the pile shrinks, not because it’s melting but because it’s becoming denser, reducing the air between the individual snowflakes. In combination with the pile’s reduced surface area, this makes the snow cold and insulated enough that not even a sunny day will cause significant melt-off. (Neil DeGrasse Tyson once likened the phenomenon to trying to cook an entire potato with a lighter; successfully raising the inner temperature of a dense snowball, much less a gigantic snow pile, requires more heat.)

Shockingly little snow melts during storage. Snow Secure reports a melt rate of 8% to 20% on piles that can be 50,000 cubic meters in size, or the equivalent of about 20 Olympic swimming pools. When autumn eventually returns, ski areas can uncover their piles of farmed snow and spread it across a desired slope or trail using snowcats, specialized groomers that break up and evenly distribute the surface. For Santa Caterina, the goal was to store enough to make a nearly 2-mile-long cross-country trail — no need to wait for the first significant snowfall of the season, which creeps later and later every year.

“In many places, November used to be more like a winter month,” Antti Lauslahti, the CEO of Snow Secure, told me. “Now it’s more like a late-autumn month; it’s quite warm and unpredictable. Having that extra few weeks is significant. When you cannot open by Thanksgiving or Christmas, you can lose 20% to 30% of the annual turnover.”

Though the concept of snow farming is not new — Lauslahti told me the idea stems from the Finnish tradition of storing snow over the summer beneath wood chips, once a cheap byproduct of the local logging industry — the company's polystyrene mat technology, which helps to reduce summer melt, is. Now that the technique is patented, Snow Secure has begun expanding into North America with a small team. The venture could prove lucrative: Researchers expect that by the end of the century, as many as 80% of the downhill ski areas in the U.S. will be forced to wait until after Christmas to open, potentially resulting in economic losses of up to $2 billion.

While there have been a few early adopters of snow farming in Wisconsin, Utah, and Idaho, the number of ski areas in the United States using the technique remains surprisingly low, especially given its many other upsides. In the States, the most common snow management system is the creation of artificial snow, which is typically water- and energy-intensive. Snow farming not only avoids those costs — which can also have large environmental tolls, particularly in the water-strapped West — but the super-dense snow farming produces is “really ideal” for something like the Race Centre at Canada’s Sun Peaks Resort, where top athletes train. Downhill racers “want that packed, harder, faster snow,” Christina Antoniak, the area’s director of brand and communications, told me of the success of the inaugural season of snow farming at Sun Peaks. “That’s exactly what stored snow produced for that facility.”

The returns are greatest for small ski areas, which are also the most vulnerable to climate change. While the technology is an investment — Antoniak ballparked that Sun Peaks spent around $185,000 on Snow Secure’s siding — the money goes further at a smaller park. At somewhere like Park City Mountain in Utah, stored snow would cover only a small portion of the area’s 140 miles of skiable routes. But it can make a major difference for an area down the road like the Soldier Hollow Nordic Center, which has a more modest 20 miles of cross-country trails.

In fact, the 2025-2026 winter season will be the Nordic Center’s first using Snow Secure’s technology. Luke Bodensteiner, the area’s general manager and chief of sport, told me that alpine ski areas are “all very curious to see how our project goes. There is a lot of attention on what we do, and if it works out satisfactorily, we might see them move into it.”

Ensuring a reliable start to the ski season is no small thing for a local economy; jobs and travel plans rely on an area being open when it says it will be. But for the Soldier Hollow Nordic Center, the stakes are even higher: The area is one of the planned host venues of the 2034 Salt Lake City Winter Games. “Based on historical weather patterns, our goal is to be able to make all the snow that we need for the entire Olympic trail system in two weeks,” Bodensteiner said, adding, “We envision having four or five of these snow piles around the venue in the summer before the Olympic Games, just to guarantee — in a worst case scenario — that we’ve got snow on the venue.”

Antoniak, at Canada’s Sun Peaks, also told me that their area has been a bit of a “guinea pig” when it comes to snow farming. “A lot of ski areas have had their eyes on Sun Peaks and how [snow farming is] working here,” she told me. “And we’re happy to have those conversations with them, because this is something that gives the entire industry some more resiliency.”

Of course, the physics behind snow farming has a downside, too. The same science saving winter sports is also why that giant, dirty pile of plowed snow outside your building isn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

Current conditions: A train of three storms is set to pummel Southern California with flooding rain and up to 9 inches mountain snow • Cyclone Gezani just killed at least four people in Mozambique after leaving close to 60 dead in Madagascar • Temperatures in the southern Indian state of Kerala are on track to eclipse 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

What a difference two years makes. In April 2024, New York announced plans to open a fifth offshore wind solicitation, this time with a faster timeline and $200 million from the state to support the establishment of a turbine supply chain. Seven months later, at least four developers, including Germany’s RWE and the Danish wind giant Orsted, submitted bids. But as the Trump administration launched a war against offshore wind, developers withdrew their bids. On Friday, Albany formally canceled the auction. In a statement, the state government said the reversal was due to “federal actions disrupting the offshore wind market and instilling significant uncertainty into offshore wind project development.” That doesn’t mean offshore wind is kaput. As I wrote last week, Orsted’s projects are back on track after its most recent court victory against the White House’s stop-work orders. Equinor's Empire Wind, as Heatmap’s Jael Holzman wrote last month, is cruising to completion. If numbers developers shared with Canary Media are to be believed, the few offshore wind turbines already spinning on the East Coast actually churned out power more than half the time during the recent cold snap, reaching capacity factors typically associated with natural gas plants. That would be a big success. But that success may need the political winds to shift before it can be translated into more projects.

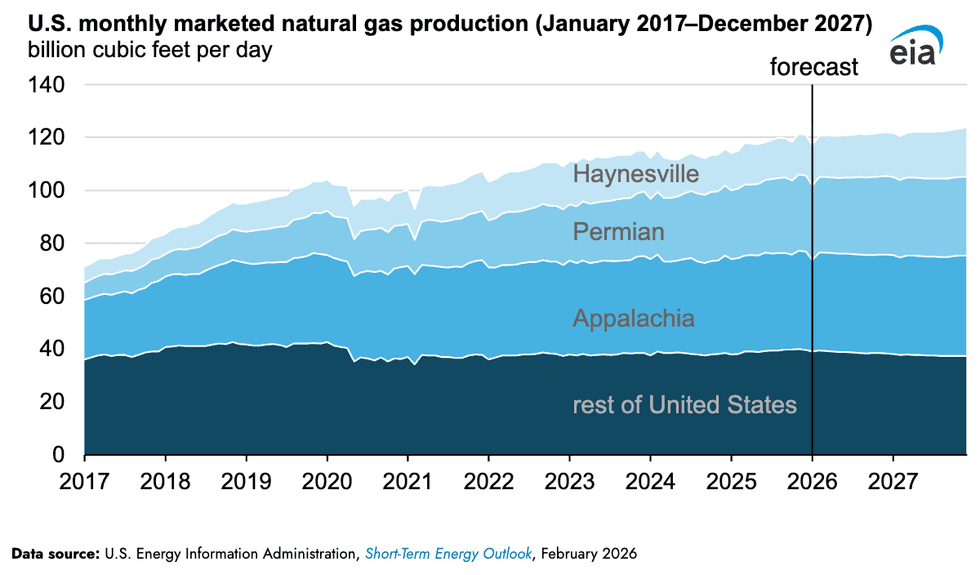

President Donald Trump’s “drill, baby, drill” isn’t moving American oil extractors, whose output is set to contract this year amid a global glut keeping prices low. But production of natural gas is set to hit a record high in 2026, and continue upward next year. The Energy Information Administration’s latest short-term energy outlook expects natural gas production to surge 2% this year to 120.8 billion cubic feet per day, from 118 billion in 2025 — then surge again next year to 122.3 billion cubic feet. Roughly 69% of the increased output is set to come from Appalachia, Louisiana’s Haynesville area, and the Texas Permian regions. Still, a lot of that gas is flowing to liquified natural gas exports, which Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin explained could raise prices.

The U.S. nuclear industry has yet to prove that microreactors can pencil out without the economies of scale that a big traditional reactor achieves. But two of the leading contenders in the race to commercialize the technology just crossed major milestones. On Friday, Amazon-backed X-energy received a license from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to begin commercial production of reactor fuel high-assay low-enriched uranium, the rare but potent material that’s enriched up to four times higher than traditional reactor fuel. Due to its higher enrichment levels, HALEU, pronounced HAY-loo, requires facilities rated to the NRC’s Category II levels. While the U.S. has Category I facilities that handle low-enriched uranium and Category III facilities that manage the high-grade stuff made for the military, the country has not had a Category II site in operation. Once completed, the X-energy facility will be the first, in addition to being the first new commercial fuel producer licensed by the NRC in more than half a century.

On Sunday, the U.S. government airlifted a reactor for the first time. The Department of Defense transported one of Valar Atomics’ 5-megawatt microreactors via a C-17 from March Air Reserve Base in California to Hill Air Force Base in Utah. From there, the California-based startup’s reactor will go to the Utah Rafael Energy Lab in Orangeville, Utah, for testing. In a series of posts on X, Isaiah Taylor, Valar’s founder, called the event “a groundbreaking unlock for the American warfighters.” His company’s reactor, he said, “can power 5,000 homes or sustain a brigade-scale” forward operating base.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

After years of attempting to sort out new allocations from the dwindling Colorado River, negotiators from states and the federal government disbanded Friday without a plan for supplying the 40 million people who depend on its waters. Upper-basin states Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and New Mexico have so far resisted cutting water usage when lower-basin states California, Arizona, and Nevada are, as The Guardian put it, “responsible for creating the deficit” between supply and demand. But the lower-basin states said they had already agreed to substantial cuts and wanted the northern states to share in the burden. The disagreement has created an impasse for months; negotiators blew through deadlines in November and January to come up with a solution. Calling for “unprecedented cuts” that he himself described as “unbelievably harsh,” Brad Udall, senior water and climate research scientist at Colorado State University’s Colorado Water Center, said: “Mother Nature is not going to bail us out.”

In a statement Friday, Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum described “negotiations efforts” as “productive” and said his agency would step in to provide guidelines to the states by October.

Europe’s “regulatory rigidity risks undermining the momentum of the hydrogen economy. That, at least, is the assessment of French President Emmanuel Macron, whose government has pumped tens of billions of euros into the clean-burning fuel and promoted the concept of “pink hydrogen” made with nuclear electricity as the solution that will make energy technology take off. Speaking at what Hydrogen Insight called “a high-level gathering of CEOs and European political leaders,” Macron, who is term-limited in next year’s presidential election, said European rules are “a crazy thing.” Green hydrogen, the version of the fuel made with renewable electricity, remains dogged by high prices that the chief executive of the Spanish oil company Repsol said recently will only come down once electricity rates decrease. The Dutch government, meanwhile, just announced plans to pump 8 billion euros, roughly $9.4 billion, into green hydrogen.

Kazakhstan is bringing back its tigers. The vast Central Asian nation’s tiger reintroduction program achieved record results in reforesting an area across the Ili River Delta and Southern Balkhash region, planting more than 37,000 seedlings and cuttings on an area spanning nearly 24 acres. The government planted roughly 30,000 narrow-leaf oleaster seedlings, 5,000 willow cuttings, and about 2,000 turanga trees, once called a “relic” of the Kazakh desert. Once the forests come back, the government plans to eventually reintroduce tigers, which died out in the 1950s.

In this special episode, Rob goes over the repeal of the “endangerment finding” for greenhouse gases with Harvard Law School’s Jody Freeman.

President Trump has opened a new and aggressive war on the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to limit climate pollution. Last week, the EPA formally repealed its scientific determination that greenhouse gases endanger human health and the environment.

On this week’s episode of Shift Key, we find out what happens next.

Rob is joined by Jody Freeman, the director of the Environmental and Energy Law Program at Harvard Law School, to discuss the Trump administration’s war on the endangerment finding. They chat about how the Trump administration has already changed its argument since last summer, whether the Supreme Court will buy what it’s selling, and what it all means for the future of climate law.

They also talk about whether the Clean Air Act has ever been an effective tool to fight greenhouse gas pollution — and whether the repeal could bring any upside for states and cities.

Shift Key is hosted by Robinson Meyer, the founding executive editor of Heatmap News.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Here is an excerpt from our conversation:

Jody Freeman: The scientific community, you know, filed comments on this proposal and just knocked all of the claims in the report out of the box, and made clear how much evidence not only there was in 2009, for the endangerment finding, but much more now. And they made this very clear. And the National Academies of Science report was excellent on this. So they did their job. They reflected the state of the science and EPA has dropped any frontal attack on the science underlying the endangerment finding.

Now, it’s funny. My reaction to that is like twofold. One, like, yay science, right? Go science. But two is, okay, well, now the proposal seems a little less crazy, right? Or the rule seems a little less crazy. But I still think they had to fight back on this sort of abuse of the scientific record. And now it is the statutory arguments based on the meaning of these words in the law. And they think that they can get the Supreme Court to bite on their interpretation.

And they’re throwing all of these recent decisions that the Supreme Court made into the argument to say, look what you’ve done here. Look what you’ve done there. You’ve said that agencies need explicit authority to do big things. Well, this is a really big thing. And they characterize regulating transportation sector emissions as forcing a transition to EVs. And so to characterize it as this transition unheralded, you know, and they need explicit authority, they’re trying to get the court to bite. And, you know, they might succeed, but I still think some of these arguments are a real stretch.

Robinson Meyer: One thing I would call out about this is that while they’ve taken the climate denialism out of the legal argument, they cannot actually take it out of the political argument. And even yesterday, as the president was announcing this action — which, I would add, they described strictly in deregulatory terms. In fact, they seemed eager to describe it not as an environmental action, not as something that had anything to do with air and water, not even as a place where they were. They mentioned the Green New Scam, quote-unquote, a few times. But mostly this was about, oh, this is the biggest deregulatory action in American history.

It’s all about deregulation, not about like something about the environment, you know, or something about like we’re pushing back on those radicals. It was ideological in tone. But even in this case, the president couldn’t help himself but describe climate change as, I think the term he used is a giant scam. You know, like even though they’ve taken, surgically removed the climate denialism from the legal argument, it has remained in the carapace that surrounds the actual ...

Freeman: And I understand what they say publicly is, you know, deeply ideological sounding and all about climate is a hoax and all that stuff. But I think we make a mistake … You know, we all get upset about the extent to which the administration will not admit physics is a reality, you know, and science is real and so on. But, you know, we shouldn’t get distracted into jumping up and down about that. We should worry about their legal arguments here and take them seriously.

You can find a full transcript of the episode here.

Mentioned:

From Heatmap: The 3 Arguments Trump Used to Gut Greenhouse Gas Regulations

Previously on Shift Key: Trump’s Move to Kill the Clean Air Act’s Climate Authority Forever

Rob on the Loper Bright case and other Supreme Court attacks on the EPAThis episode of Shift Key is sponsored by ...

This episode of Shift Key is sponsored by ...

Accelerate your clean energy career with Yale’s online certificate programs. Explore the 10-month Financing and Deploying Clean Energy program or the 5-month Clean and Equitable Energy Development program. Use referral code HeatMap26 and get your application in by the priority deadline for $500 off tuition to one of Yale’s online certificate programs in clean energy. Learn more at cbey.yale.edu/online-learning-opportunities.

Music for Shift Key is by Adam Kromelow.