You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

A little insulation goes a long way toward decarbonizing.

When you think about ways to decarbonize, your mind will likely go straight to shiny new machines — an electric vehicle, solar panels, or an induction stove, perhaps. But let’s not forget the low-tech, low-hanging fruit: your home itself.

Adding insulation, fixing any gaps, cracks or leaks where air can get out, and perhaps installing energy efficient windows and doors are the necessary first steps to decarbonizing at home — though you may also want to consider a light-colored “cool roof,” which reflects sunlight to keep the home comfortable, and electric panel and wiring upgrades to support broader electrification efforts.

Getting started on one or multiple of these retrofits can be daunting — there’s lingo to be learned, audits to be performed, and various incentives to navigate. Luckily, Heatmap is here to help.

Cora Wyent is the Director of Research at Rewiring America, where she conducts research and analysis on how to rapidly electrify the entire economy.

Joseph Lstiburek is the founding principal at the Building Science Corporation, a consulting firm focused on designing and constructing energy efficient, durable, and economic buildings.

Lucy de Barbaro is the founder and director of Energy Efficiency Empowerment, a Pittsburgh-based organization that seeks to transform the home renovation process and help low and middle-income homeowners make energy efficiency improvements.

Definitively, yes! When people hear the word “insulation” they often think of how it can protect them from the cold. And while it certainly does do that, insulation’s overall role is to slow the transfer of heat both out of your home when it’s chilly and into your home when it’s hot. That means you won’t need to use your air conditioning as much during those scorching summer days or your furnace as much when the temperatures drop.

Quite possibly! The most definitive way to know if your home could be improved by weatherization is by getting a home energy audit —- more on that below. While a specific level of insulation is required for all newly constructed homes, these codes and standards are updated frequently. So if you’re feeling uncomfortable in your living space, or if you think your heating and cooling bills are unusually high, it’s definitely worth seeing what an expert thinks. And if you’re interested in getting electric appliances like a heat pump or induction stove, some wiring upgrades will almost certainly be necessary.

Energy efficient appliances like electric heat pumps or induction stoves are fantastic ways to decarbonize your life, but serve a fundamentally different purpose than most of the upgrades that we’re going to talk about here. When you get better air sealing, insulation, windows, or doors, what you’re doing is essentially regulating the temperature of your home, making you less reliant on energy intensive heating and cooling systems. And while this can certainly lead to savings on your energy bill and a positive impact on the environment at large, these upgrades will also allow you to simply live more comfortably.

This is the starting point for making informed decisions about any energy efficiency upgrades that you’re considering. During a home energy audit, a certified auditor (sometimes also referred to as an energy assessor or rater or verifier) will inspect your home to identify both the highest-impact and most cost-effective upgrades you can make, including how much you stand to save on your energy bills by doing so.

Wyent told me checking with your local utility is a good place to start, as many offer low-cost audits. Even if your utility doesn’t do energy assessments, they may be able to point you in the direction of local auditors or state-level resources and directories. The Residential Energy Services Network also provides a directory of certified assessors searchable by location, as does the Department of Energy’s Energy Score program, though neither list is comprehensive.

Audits typically cost between $200 and $700 depending on your home’s location, size, and type, as well as the scope of the audit. Homeowners can claim 30% of the cost of their audit on their federal taxes, up to $150. To be eligible, make sure you find a certified home energy auditor. The DOE provides a list of recognized certification programs.

Important: Make sure the auditor performs both a blower door test and a thermographic inspection. These diagnostic tools are key to determining where air leakage and heat loss/gain is occurring.

Your energy audit isn’t the only thing eligible for a credit. The 25C Energy Efficient Home Improvement Credit allows homeowners to claim up to 30% of the cost of a variety of home upgrades, up to a combined total of $1,200 per year. This covers upgrading your insulation, windows, doors, skylights, electrical wiring, and/or electrical panel. Getting an energy audit is also included in this category.

While $1,200 is the max amount you can claim for all retrofits combined, certain renovations come with their own specific limitations. Let’s break it down:

State and local incentives:

Depending on where you live, there may be additional state and local incentives, and we suggest asking your contractor what you are eligible for. But since incentive programs change frequently, it’s a good idea to do your own research too. Get acquainted with Energy Star, a joint program run by the Environmental Protection Agency and the DOE which provides information on energy efficient products, practices, and standards. On Energy Star’s website, you can search by zip code for utility rebates that can help you save on insulation, windows, and electrical work.

“Starting by looking at your local utility programs can be a great resource too, because utilities offer rebates or incentives for weatherizing your home or installing a new roof,” said Wyent.

Everyone wants to minimize the number of times they break open or drill into their walls. To that end, it’s useful to plan out all the upgrades you might want to get done over the next five to 10 years to figure out where efficiency might fit in.

Some primary examples: Installing appliances like a heat pump, induction stove, or Level 2 EV charger (all of which you can read more about in our other guides) often require electrical upgrades. Even if you don’t plan to get any of these new appliances now, pre-wiring your home to prepare for their installation (with the exception of a heat pump — see our heat pump guide for more info on that) will save you money later on.

De Barbaro also notes that if you’re planning to repaint your walls anytime soon, this would also be a convenient time to add insulation, as that involves drilling holes which then need to be patched and repainted anyway. Likewise, if you were already planning to replace your home’s siding, this would be a natural time to insulate. Finally, if you’re planning to get a heat pump in the coming years, getting better insulation now will ensure this system is maximally effective.

Conversely, if you’re cash-strapped, spreading out electrical and weatherization upgrades over the course of a few years allows you to claim the full $1,200 tax credit every year. Whether those tax savings are enough to cover the added contractor time and clean-up costs, though, will depend on the particulars of your situation.

“Come in with a plan and talk to the contractor about everything that you want to do in the future, not just immediately,” said Wyent.

Unlike solar installers, which are often associated with large regional and national companies, the world of weatherization and electrical upgrades is often much more localized, meaning you’ll need to do a bit of legwork to verify that the contractors and installers you come across are reliable.

Wyent told me she typically starts by asking friends, family, and neighbors for references, as well as turning to Google and Yelp reviews. Depending on where you live and what type of work you want done, your local utility may also offer incentives for weatherization and electrification upgrades, and can possibly provide a list of prescreened contractors who are licensed and insured for this type of work.

These questions will help you vet contractors and gain a better understanding of their process regardless of the type of renovation you’re pursuing.

Common wisdom says you should always get three quotes. But that doesn’t mean you should automatically choose the cheapest option. Lstiburek says the old adage applies: “If it sounds too good to be true, it's probably too good to be true.” Be sure that your contractors and installers are properly licensed and insured and read the fine print of your contract. Beyond this, how to find qualified professionals and what to ask largely depends on the type of upgrade you are pursuing. So let’s break it down, starting with the biggest bang for your buck.

Air sealing and insulating your home is usually the number one way to increase its energy efficiency. Energy Star says nine out of 10 homes are underinsulated, and many also have significant air leaks. In general, homes lose more heating and cooling energy through walls and attics than through windows and doors, so air sealing and adding insulation in key areas should be your first priority.

“People don't realize how collectively, small holes everywhere add up. So on average here in Pennsylvania, typically those holes would add up to the surface of three sheets of paper, continuously open to the outdoors,” said de Barbaro.

Determining where air is escaping is the purpose of the blower door test and the thermographic inspection, so after your energy audit you should have a good idea of where to begin with these retrofits. This guide from the Department of Energy is a great resource on all the places in a home one might consider insulating.

Choosing an insulation type:

Every home is different, and the type of insulation you choose will depend on a number of factors including where you’re insulating, whether that area is finished or unfinished, what R-Value is right for your climate, and your budget. You can check out this comprehensive list of different insulation types to learn about their respective advantages and use cases. But when it comes to attic rafters and exterior walls, De Barbaro said that one option rises above the rest.

“The magic word here is dense-packed cellulose insulation!” De Barbaro told me.

This type of insulation (which falls under the “loose fill and blown-in” category) is made from recycled paper products, meaning it has very low embodied carbon emissions. It’s also cheap and effective. For exterior walls and attic rafters, be sure to avoid loose-fill cellulose, as that can settle and become less effective over time — although for attic floors, loose-fill works well. Both are installed by drilling holes into the wall or floor space and blowing the insulation in under pressure.

We recommend discussing all of these options with your contractor, but here are the other materials you’re most likely to come across:

In addition to asking friends, family, and your local utility for contractor recommendations, Energy Star specifically recommends these additional resources where you can find licensed and insured contractors for insulation work.

While air sealing and insulation should definitely be number one on your weatherization checklist, plenty of heat gets lost through windows, doors, and skylights, as well. Single pane glass is a particularly poor insulator, and while fewer houses these days have it, upgrading to double or triple pane windows or skylights can be a big energy saver. Likewise, steel or fiberglass doors are much better insulators than traditional wooden doors.

But be warned: These can be pricey upgrades. The cost of installing windows alone ranges from hundreds of dollars up to $1,500 per window, and many homes have ten or more. It’s unlikely you’ll fully recoup the outlay through your energy savings, so before going about these retrofits, be sure that you’ve taken care of the easy stuff first.

Once you’ve done your research, it’s time to schedule a consultation with an installer, who can help you refine your project needs, discuss design and installation options, and provide you with a quote.

“So if you pick a Marvin window, make sure that you have a Marvin certified installer in your location, installing the Marvin window according to the Marvin instructions.” said Lstiburek.

Insulating your attic floor or your roof rafters is the best way to ensure that your home is sealed off from the elements. But if you live in a hot climate and need a new roof anyway (most last 25 to 50 years), then you might consider getting a cool roof, which can be made from a variety of materials and installed on almost any slope. However, they won’t lead to energy efficiencies in all geographies, so be sure to do your research beforehand!

Last but certainly not least is a retrofit that’s a little different from the rest. Unlike getting insulation, new windows, or a new roof, upgrading your wiring or electric panel doesn’t lead to greater energy efficiency by regulating the temperature of your home. What it does instead is enable greater energy efficiency by making it possible to operate an increasing number of electrified appliances and devices in your house.

For example, getting an electric or induction stove or dryer, a standard heat pump, a heat pump water heater, or an electric vehicle charger will require that you add new electric circuits to support these devices. And as these new loads add up, you may need to install a larger electric panel to support it all.

After sourcing electrician recommendations from family and friends, a good place to turn is Rewiring America’s contractor directory network. (Rewiring America is also a sponsor of Decarbonize Your Life.)Networks in your area can then provide you with a list of qualified electricians.

“Most people are really only using somewhere around 40% of what their current panels space. So you can actually add a fair amount of new circuits to your existing panel and upgrade your wiring while not having to upgrade your panel at all,” Wyent said.

Once you have three quotes in hand, all that’s left to do is evaluate your options, choose a contractor or installer, and sign a contract. Cost will likely be a major factor in the decision, but you’ll also want to ensure that the cheapest quote doesn’t mean corners will be cut. Here’s what to look out for.

Pay close attention to warranties. This applies both to the warranty for the work being performed and to the warranties for the products themselves. If an installation job or a product is well priced but comes with a short warranty, this should give you pause.

Avoid “same day signing specials.” If you’re being rushed into signing a contract, this is also a bad sign. Be sure to read the fine print — most cost estimates should be good for a few weeks at minimum.

Get specific. Your quotes should specify the type of work being performed, the scope of the work, cost (broken down by materials, labor, permits, and other expenses), payment method, and a tentative timeline for completion. A quote is much less formal than a contract, so if some of this information isn’t provided up front, don’t hesitate to ask for clarification so that you can make apples-to-apples comparisons between different contractors.

When you get a contract in hand, double check that:

Then it’s time to sign, sit back, and enjoy the soothing sounds of hammering, drilling, insulation blowing, and wire tinkering, content in knowing that you’re decarbonizing your home down to its very bones!

Now that you’re living comfortably in a maximally energy efficient home, you’re probably wondering when you’ll start seeing all those incentives you researched pay off. First off, know that you must wait until all renovations are complete and paid for to claim your federal tax credit. That means that even if you purchased new windows this year, if you have them installed in 2025, you’ll file for a tax credit with your 2025 return. Here’s how to go about it.

For state and local incentives, check the website for your local utility as well your local and state government and energy office to see what documentation is required. When in doubt, keep all of your records and receipts!

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Heron Power and DG Matrix each score big funding rounds, plus news for heat pumps and sustainable fashion.

While industries with major administrative tailwinds such as nuclear and geothermal have been hogging the funding headlines lately, this week brings some variety with news featuring the unassuming but ever-powerful transformer. Two solid-state transformer startups just announced back-to-back funding rounds, promising to bring greater efficiency and smarter services to the grid and data centers alike. Throw in capital supporting heat pump adoption and a new fund for sustainable fashion, and it looks like a week for celebrating some of the quieter climate tech solutions.

Transformers are the silent workhorses of the energy transition. These often-underappreciated devices step up voltage for long-distance electricity transmission and step it back down so that it can be safely delivered to homes and businesses. As electrification accelerates and data centers race to come online, demand for transformers has surged — more than doubling since 2019 — creating a supply crunch in the U.S. that’s slowing the deployment of clean energy projects.

Against this backdrop, startup Heron Power just raised a $140 million Series B round co-led by Andreessen Horowitz and Breakthrough Energy Ventures to build next-generation solid state transformers. The company said its tech will be able to replace or consolidate much of today’s bulky transformer infrastructure, enabling electricity to move more efficiently between low-voltage technologies like solar, batteries, and data centers and medium-voltage grids. Heron’s transformers also promise greater control than conventional equipment, using power electronics and software to actively manage electricity flows, whereas traditional transformers are largely passive devices designed to change voltage.

This new funding will allow Heron to build a U.S.manufacturing facility designed to produce around 40 gigawatts of transformer equipment annually; it expects to begin production there next year. This latest raise follows quickly on the heels of its $38 million Series A round last May, reflecting hunger among customers for more efficient and quicker to deploy grid infrastructure solutions. Early announced customers include the clean energy developer Intersect Power and the data center developer Crusoe.

It’s a good time to be a transformer startup. DG Matrix, which also develops solid-state transformers, closed a $60 million Series A this week, led by Engine Ventures. The company plans to use the funding to scale its manufacturing and supply chain as it looks to supply data centers with its power-conversion systems.

Solid-state transformers — which use semiconductors to convert and control electricity — have been in the research and development phase for decades. Now they’re finally reaching the stage of technical maturity needed for commercial deployment, driving a surge in activity across the industry. DG Matrix’s emphasis is on creating flexible power conversion solutions, marketing its product as the world’s first “multi-port” solid-state transformer capable of managing and balancing electricity from multiple different sources at once.

“This Series A marks our transition from breakthrough technology to scaled infrastructure deployment,” Haroon Inam, DG Matrix’s CEO, said in a statement. “We are working with hyperscalers, energy companies, and industrial customers across North America and globally, with multiple gigawatt-class datacenters in the pipeline.” According to TechCrunch, data centers make up roughly 90% of DG Matrix’s current customer base, as its transformers can significantly reduce the space data centers require for power conversion.

Zero Homes, a digital platform and marketplace that helps homeowners manage the heat pump installation process, just announced a $16.8 million Series A round led by climate tech investor Prelude Ventures. The company’s free smartphone app lets customers create a “digital twin” of their home — a virtual model that mirrors the real-world version, built from photos, videos, and utility data. This allows homeowners to get quotes, purchase, and plan for their HVAC upgrade without the need for a traditional in-person inspection. The company says this will cut overall project costs by 20% on average.

Zero works with a network of vetted independent installers across the U.S., with active projects in California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Illinois. As the startup plans for national expansion, it’s already gained traction with some local governments, partnering with Chicago on its Green Homes initiative and netting $745,000 from Colorado’s Office of Economic Development to grow its operations in Denver.

Climactic, an early-stage climate tech VC, launched a new hybrid fund called Material Scale, aimed at helping sustainable materials and apparel startups navigate the so-called “valley of death” — the gap between early-stage funding and the later-stage capital needed to commercialize. As Climactic’s cofounder Josh Fesler explained on LinkedIn, the fund is designed to cover the extra costs involved with sustainable production, bridging the gap between the market price of conventional materials and the higher price of sustainable materials.

Structured as a “hybrid debt-equity platform,” the fund allows Climactic’s investors to either take a traditional equity stake in materials startups or provide them with capital in the form of loans. TechCrunch reports that the fund’s initial investments will come from an $11 million special purpose vehicle, a separate entity created to fund a small set of initial investments that sits outside Material Scale’s main investing pool.

The fashion industry accounts for roughly 10% of global emissions. “These days there are many alt materials startups that have moved through science and structural risk, have venture funding, credible supply chains and most importantly can achieve market price and positive gross margins just with scale,” Fesler wrote in his LinkedIn post. “They just need the capital to grow into their rightful commercial place.”

Clean energy stocks were up after the court ruled that the president lacked legal authority to impose the trade barriers.

The Supreme Court struck down several of Donald Trump’s tariffs — the “fentanyl” tariffs on Canada, Mexico, and China and the worldwide “reciprocal” tariffs ostensibly designed to cure the trade deficit — on Friday morning, ruling that they are illegal under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act.

The actual details of refunding tariffs will have to be addressed by lower courts. Meanwhile, the White House has previewed plans to quickly reimpose tariffs under other, better-established authorities.

The tariffs have weighed heavily on clean energy manufacturers, with several companies’ share prices falling dramatically in the wake of the initial announcements in April and tariff discussion dominating subsequent earnings calls. Now there’s been a sigh of relief, although many analysts expected the Court to be extremely skeptical of the Trump administration’s legal arguments for the tariffs.

The iShares Global Clean Energy ETF was up almost 1%, and shares in the solar manufacturer First Solar and the inverter company Enphase were up over 5% and 3%, respectively.

First Solar initially seemed like a winner of the trade barriers, however the company said during its first quarter earnings call last year that the high tariff rate and uncertainty about future policy negatively affected investments it had made in Asia for the U.S. market. Enphase, the inverter and battery company, reported that its gross margins included five percentage points of negative impact from reciprocal tariffs.

Trump unveiled the reciprocal tariffs on April 2, a.k.a. “liberation day,” and they have dominated decisionmaking and investor sentiment for clean energy companies. Despite extensive efforts to build an American supply chain, many U.S. clean energy companies — especially if they deal with batteries or solar — are still often dependent on imports, especially from Asia and specifically China.

In an April earnings call, Tesla’s chief financial officer said that the impact of tariffs on the company’s energy business would be “outsized.” The turbine manufacturer GE Vernova predicted hundreds of millions of dollars of new costs.

Companies scrambled and accelerated their efforts to source products and supplies from the United States, or at least anywhere other than China.

Even though the tariffs were quickly dialed back following a brutal market reaction, costs that were still being felt through the end of last year. Tesla said during its January earnings call that it expected margins to shrink in its energy business due to “policy uncertainty” and the “cost of tariffs.”

Current conditions: More than a foot of snow is blanketing the California mountains • With thousands already displaced by flooding, Papua New Guinea is facing more days of thunderstorms ahead • It’s snowing in Ulaanbaatar today, and temperatures in the Mongolian capital will plunge from 31 degrees Fahrenheit to as low as 2 degrees by Sunday.

We all know the truisms of market logic 101. Precious metals surge when political volatility threatens economic instability. Gun stocks pop when a mass shooting stirs calls for firearm restrictions. And — as anyone who’s been paying attention to the world over the past year knows — oil prices spike when war with Iran looks imminent. Sure enough, the price of crude hit a six-month high Wednesday before inching upward still on Thursday after President Donald Trump publicly gave Tehran 10 to 15 days to agree to a peace deal or face “bad things.” Despite the largest U.S. troop buildup in the Middle East since 2003, the American military action won’t feature a ground invasion, said Gregory Brew, the Eurasia Group analyst who tracks Iran and energy issues. “It will be air strikes, possibly commando raids,” he wrote Thursday in a series of posts on X. Comparisons to Iraq “miss the mark,” he said, because whatever Trump does will likely wrap up in days. The bigger issue is that the conflict likely won’t resolve any of the issues that make Iran such a flashpoint. “There will be no deal, the regime will still be there, the missile and nuclear programs will remain and will be slowly rebuilt,” Brew wrote. “In six months, we could be back in the same situation.”

California, Colorado, and Washington led 10 other states in suing the Trump administration this week over the Department of Energy’s termination of billions in federal funding for clean energy and infrastructure projects. In a lawsuit filed in federal court in San Francisco, the states accuse the agency of using a “nebulous and opaque” review process to justify slashing billions in funding that was already awarded. “These aren’t optional programs — these are investments approved by bipartisan majorities in Congress,” California Attorney General Rob Bonta said at a press conference announcing the lawsuit, according to Courthouse News Service. “The president doesn’t get to cancel them simply because he disagrees with them. California won’t allow President Trump and his administration to play politics with our economy, our energy grid and our jobs.”

Get Heatmap AM directly in your inbox every morning:

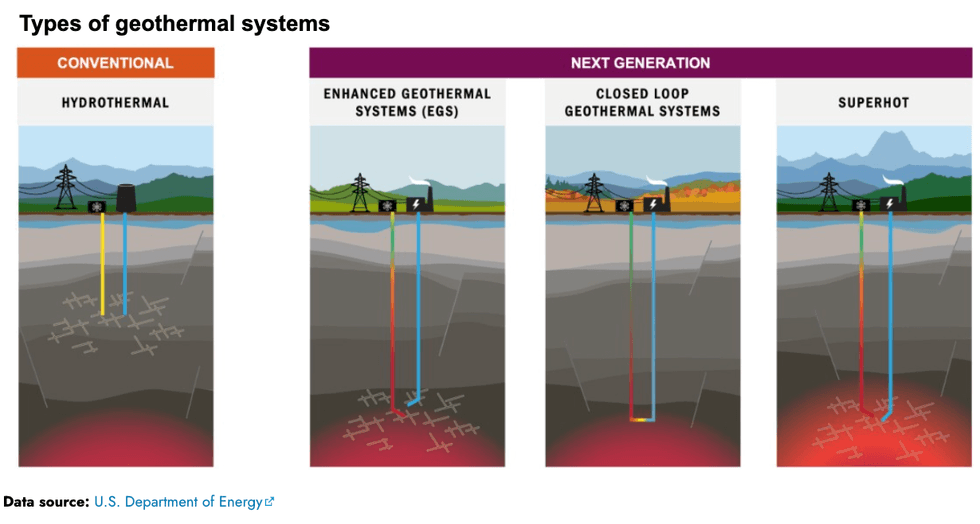

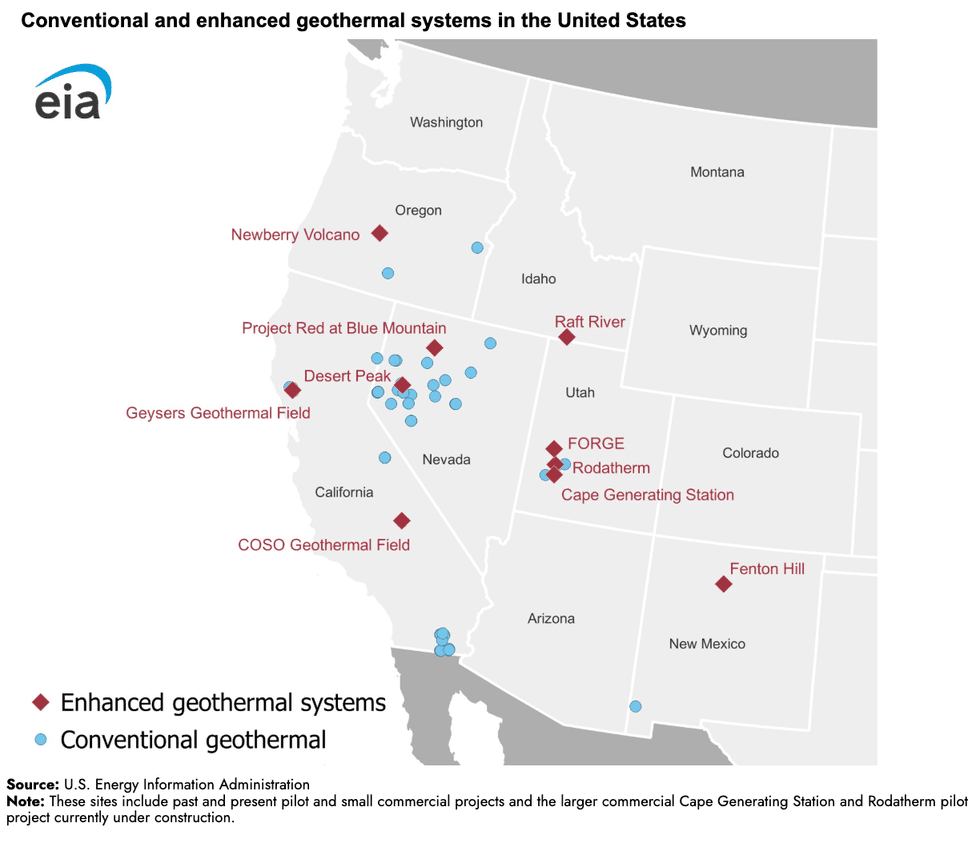

If you’re looking for a sign of the coming geothermal energy boom in the U.S., consider this: There is now a double-digit number of next-generation projects underway, according to an overview the Energy Information Administration published Thursday. For the past century, geothermal energy has relied upon finding and tapping into suitably hot underground reservoirs of water. But a new generation of “enhanced” geothermal companies is using modern drilling techniques to harness heat from dry rocks.

If you’re looking for a thorough overview of the technology, Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote the definitive 101 explainer here. But a few represent some of the earliest experiments in enhanced geothermal, including the Fenton Hill in New Mexico, established in the 1970s, which was the world’s first successful project to use the technology.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

When Exxon Mobil announced plans in December to scale back its spending on low-carbon investments, the oil giant justified the move in part on all the carbon capture and storage projects poised to come online this year that would vault the company ahead of its rivals. This week, Exxon Mobil started transporting and storing captured carbon dioxide at its latest facility in Louisiana. The New Generation Gas Gathering facility on the western edge of the state’s Gulf Coast is the company’s second CCS project in Louisiana. Known as NG3, the project is set to remove 1.2 million tons of CO2 per year from gas streams headed to export markets on the coast. The Carbon Herald reported that two additional CCS projects are set to start up operations this year.

CCS got a big boost in October when Google agreed to back construction of a gas-fired power plant built with carbon capture tech from the ground up. The plant, which Matthew noted at the time would be the first of its kind at a commercial scale, is sited near a well where captured carbon can be injected. Senate Democrats, meanwhile, are reportedly probing the Trump administration’s decision to redirect CCS funding to coal plants.

In 2019, Maine expanded its Net Energy Billing program to subsidize construction of commercial-scale solar farms across the state. “And it worked,” Maine Public Radio reported last July when the state passed a law to phase out the funding, “too well, some argue.” In 2025 alone, ratepayers in the state were on the hook for $234 million to support the program. Solar companies sued, arguing that the abrupt cut to state support had unfairly deprived them of funding. But this week U.S. District Judge Stacey Neumann denied a motion the owners of dozens of solar farms filed requesting an injunction.

That isn’t to say things aren’t looking sunny for solar in Maine. On the contrary, just yesterday the developer Swift Current Energy secured $248 million in project financing for a 122-megawatt solar farm and the Poland Spring water company went on statewide TV to show off the new panels on its bottling plant. The federal outlook isn’t as bright at the moment. As Heatmap’s Jael Holzman reported in December, the solar industry was begging Congress for help to end the Trump administration’s permitting blockade on new projects on federal lands.

The Trump-stumping country music star John Rich is continuing his crusade against the Tennessee Valley Authority. Months after blocking construction of a gas plant in his neighborhood, Rich personally pressed TVA CEO Don Moul to reroute a transmission line, posting a video Thursday of farmers who opposed the federal utility’s use of the right of way process to push through the project. Rich said Moul “personally told me as of this morning” TVA will put the effort on hold. The left-wing energy writer and Heatmap contributor Fred Stafford summed it up this way on X: “MAGA NIMBY rises, Dark Abundance falls. TVA ratepayers will be paying more for a rerouted transmission project because this country music star threw his support behind a local farmer who refuses to allow the transmission line to cross his land.”