You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Can solar plus storage fix one of the thorniest problems of the energy transition?

To talk about renewable energy these days is to talk about power lines. “No transition without transmission” has become something of a mantra among a legion of energy wonks. And following the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, which contains a massive pot of subsidies for non-carbon-emitting power but little in the way of delivering it, legislative and regulatory attention has turned to getting that power from where it’s sunny and windy to where it’s needed.

Hardly a day goes by in which some industry group or environmental nonprofit isn’t assaulting the inboxes of climate journalists like myself with another study or white paper stressing the need for more transmission. But I’ve also recently noticed a newer group of advocates popping up: the battery stans.

Now, virtually everyone in the renewable energy space loves talking about the massive growth and potential of batteries to store power generated by renewables for when it’s needed most. Here the Inflation Reduction Act’s honeypot of subsidies and the long economic trends are working together. The price of batteries really is falling dramatically, and their deployment has been ramped up.

For most people, batteries are a complement to transmission upgrades. But to a much smaller group, the falling prices of solar and batteries may obviate the need for transmission expansion entirely.

Let’s start with the more mild case. As Duncan Campbell, Vice President at Scale Microgrids told me, “If you go deep on power grid expansion modeling studies, they all assume an enormous build-out of transmission well beyond what we’ve done in the past and I think demonstrated to be well beyond the current institutional capacity.” In other words, you can pencil in as much transmission build-out as you want, but the chances we’ll actually do it seem at least short of certain. “It’s quite reasonable to suggest when doing something super ambitious that it’s a good idea to have a diversified approach,” he said.

That diversified approach, for Campbell, includes storage and generation both on the transmission part of the grid — like utility-scale storage paired with solar arrays — and on the distribution side of the grid, like rooftop solar and garage batteries. The latter two examples can also work together as a “virtual power plant” to modulate consumption based on when power is most expensive or cheap and even sometimes send power back to the grid at times of stress.

“At the end of the day it seems undeniably prudent to think about what solutions are going to complement large-scale transmission build-out if we want to meet these goals. Otherwise it’s a concentrated approach that carries a lot of risks,” Campbell told me. “Technologically, VPPs and DER [distributed energy resources] can help. Especially in those worst situations.”

This balanced approach would not actually face much opposition from advocates for a substantial transmission build-out, even if sometimes this “debate” — especially on Twitter, I’m sorry, especially on X — can get polarized and contentious.

“They’re complementary, not competitive,” Ric O’Connell, the executive director of GridLab, told me. “Transmission moves energy around in space, storage moves around in time. You need both.”

O’Connell pointed out that storage in some cases could be thought of a transmission asset, something analogous to the wires and poles that move electricity, where power could be moved on very short time frames to help out with extremely high levels of demand, a lack of generation, or transmission congestion. We’ve seen this already in Texas, where storage has helped take the bite out of extremely high demand recently, and in California, where it has helped alleviate the rapid disappearance of solar power every evening.

“The shorter duration storage stuff is working to address congestion and streamline transmission operations. In that sense you can put it in the same category as a grid enhancing technology,” O’Connell said.

While nearly everyone I talked to was eager to say that storage and transmission could complement each other, even if some leaned on transmission more and others were more bullish on storage and distributed energy, there was one person who actually did represent a clear and polarizing view: Casey Handmer.

Handmer is a Cal Tech trained physicist who used to write software for the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and founded Terraform Industries, an early stage start up that’s looking to develop the “Terraformer,” a solar-powered factory that would create synthetic natural gas. Immodestly, he “aims to displace the majority of fossil hydrocarbon production by 2035.”

More modestly, he describes himself as “effectively a puffed up blogger who runs a pre-revenue (i.e. default dead) startup in an area peripheral (at best) to grid issues,” but is nonetheless, again, immodestly “pretty confident that my analysis is correct,” he told me in an email.

“My views on this matter are unconventional, even controversial. Arguably this is my spiciest hot take on the future of energy,” he wrote on his blog.

He thinks that the falling price of solar and batteries will make large-scale transmission investments unnecessary.

The price declines in battery and solar will continue, allowing people and businesses to throw up solar wherever, pair it with batteries, to the point where solar is “5-15x” overbuilt. That would mean that solar wouldn’t need to be backed up by any kind of “clean firm” power, i.e. a source that can produce carbon-free electricity at any time, like nuclear power, pumped-hydro, green hydrogen, or natural gas with carbon capture and storage.

While extreme, his views are not so, so, so far off from other renewables maximalists, who view solar and battery price declines as essentially inexorable. If they’re right, resource adequacy issues (i.e. that it’s much more sunny in some places than others) could be overcome by just building more cheap solar and installing more batteries.

“Adding 12 hours of storage to the entire U.S. grid would not happen overnight, but on current trends would cost around $500 billion and pay for itself within a few years. This is a shorter timescale than the required manufacturing ramp, meaning it could be entirely privately funded. By contrast, upgrading the U.S. transmission grid could cost $7 trillion over 20 years,” Handmer wrote in July.

As for the case that transmission is needed to get solar power from where it’s sunnier (like southern Europe or the American Southwest) to where it isn’t (Northern Europe, the rest of America), Handmer argues this isn’t really a problem.

“Solar resource quality doesn't matter that much. Solar resource is much more evenly distributed than, say, oil,” he told me. “Almost all humans live close to where their grandparents were able to grow food to live, and crops only grow in places that are roughly equally sunny.” He also argued that “solar is about 1000x more productive in terms of energy produced per unit land used than agriculture,” so building it will be economically compelling in huge swathes of the world.

As he acknowledges, his view is pretty lonely. He seems to yada-yada away what developments in battery technology would be needed to make this all work (although presumably ever-cheapening solar could just charge more lithium-ion batteries). One estimate suggests that to have “the greatest impact on electricity cost and firm generation,” battery storage would have to extend out to 100 hours — about 25X more than they do now.

This is where I say what you’re already thinking. This combination of technofuturism, contrarianism, work experience in the space industry and comfort with back-of-the-envelope math to make strong assertions makes Handmer sound like — and I mean this in the most value-neutral, descriptive way possible — another proponent of the rooftop solar, home battery, electric car future: Elon Musk. (Handmer used to work at the Musk-inspired Hyperloop One).

When I asked him why he’s an admitted outlier on this, he chalked it up to “anchoring bias in the climate space ... before solar and batteries got cheap, analyses showed that increasing the size of the grid was the best way to counter wind intermittency. But when the assumptions and data change, the results change too. The future of electricity is local. As a physicist, I was trained to take unusual observations to their utmost conclusion.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

A test drive provided tantalizing evidence that a great, cheap EV is possible for the U.S.

Midway through the tortuous test drive over the mountains to Malibu, as the new Chevrolet Bolt EV ably zipped through a series of sharp canyon corners, I couldn’t help but think: Who would want to kill this car?

Such is life for the Bolt. Chevy revived the budget electric car after its fans howled when it killed the first version in 2023. But by the time the car press assembled last week for the official test drive of Bolt 2.0, the new car already had an expiration date: General Motors said it would end the production run next summer. This is a shame for a variety of reasons. Among the most important: The new Bolt, which starts just under $30,000 and is soon to start arriving at Chevy dealerships, shows that the cheap EV for the masses is really, almost there.

The 2027 Bolt comes with a 65 kilowatt-hour lithium iron phosphate battery that’s rated to deliver 262 miles of range. That’s not bad for an economy car, given that lots of more expensive EVs came with ranges in the low 200s just a couple of years ago.

Charging speed, the big bugaboo with the original Bolt, is fixed. The glacial 50-kilowatt speed has risen to 150 kilowatts, allowing the car to charge from 10% to 80% in about 25 minutes. That pales in comparison to the 350-kilowatt Hyundai touts for some of its EVs, but it makes the Bolt road trip an acceptable experience, not a slog. Crucially, the new Bolt comes with the NACS port and will seamlessly plug-and-charge at many charging stations, including Tesla’s.

Bolt comes with a single motor that delivers 210 horsepower and 169 pound-feet of torque — not eye-popping numbers. But because all of an electric car’s torque is available at any time, the Bolt feels livelier as it accelerates away from a start compared to an equivalent combustion-powered economy car. It huffs and puffs just a tad trying to accelerate uphill on California’s mountain highways, sure, but Bolt has enough oomph to have some fun without getting you into trouble. And in a world of white cars, Bolt comes in honest-to-goodness colors. Red. Blue. Yellow!

The tech features are the same story — that is, plenty good for the price. Many Bolt loyalists are incensed that Chevy killed off Apple Carplay and Android Auto integration in the new car, forcing drivers to rely on what’s built in. For those who can get over the disappointment, what is built into Bolt’s 11-inch touchscreen is pretty good, starting with Google Maps integration for navigation. Its method for displaying charging stations — and allowing the driver to filter them by plug style, provider, and other factors — isn’t quite up to the Silicon Valley seamlessness of a Rivian, but is easier to use than what a lot of legacy car companies put in their EVs. (The fabulous Kia EV9 three-row SUV I tested just before the Bolt is superior in just about every way except this.)

The Bolt even has a few features you wouldn’t expect at the entry level. The surround vision recorder for storing footage from the car’s camera is a first for a GM vehicle, Chevy says. The brand is also making a big to-do over the Super Cruise hands-free driving feature since the Bolt is now the least expensive car to get it, though adding all that tech takes the basic LT version of the Bolt up from $29,000 to more than $35,000, which is the starting price for the bigger Chevy Equinox EV.

With so much going right for this vehicle, why preemptively kill it? The most obvious factor is the Trump White House. Chevrolet had always called the Bolt’s return a limited run, but the fact that its production run might last for just a year and a half is a direct result of Trump tariffs: GM wants to make gas-powered Buick crossovers, currently made in China, at the Kansas factory that builds the Bolt.

And the loss last year of the federal incentive to buy an EV is particularly punitive for the Bolt. With $7,500 shaved off the price, the Chevy EV would have been cost-competitive with the cheapest new gas cars, like the Hyundai Elantra or Toyota Corolla. Without it, Bolt is closer in price to a larger vehicle like the Toyota RAV4. When Chevy can’t make the case that its EV is as cheap as any other small car you might be looking at, it must sell a car like Bolt on its down-the-road value: very little routine maintenance, no buying gasoline during a period of wartime oil shocks, and so on. That’s a tougher task, and perhaps explains why GM was so quick to move on.

Still, there’s clearly something bigger at stake here for GM. The American car companies’ pivot back to the short-term profitability of petroleum, exemplified by the Bolt-Buick affair, comes as the rest of the world continues to embrace EVs. Headlines lately have wondered whether China’s ascent combined with America’s yoyo-ing on electric power could lead to Detroit’s outright demise, leaving the U.S. auto industry with scraps as someone else’s superior EVs take over the world.

In this light, Chevy’s own market data on Bolt is especially jarring. Of the nearly 200,000 Bolts on the road from the car’s previous generation, 75% percent of those drivers came from other car companies to GM, and 72% remained loyal to GM. In other words, the new Bolt is set to build on General Motors’ status as the top EV-seller in America behind Tesla by expanding the established base of customers who love Chevy electric cars. That is what’s being tossed aside to increase quarterly profits.

Maybe the Bolt will surprise its maker, again. Even if a groundswell of enthusiasm for the new car isn’t enough to save it from extinction, perhaps it will prove to GM to give the budget EV yet another go-around when the market shifts yet again.

Current conditions: Spring-like temperatures have arrived in New York City, with a high of 62 degrees Fahrenheit today • The death toll from the flooding in Nairobi, Kenya, has risen to at least 42 • Heavy rain in Peru threatens landslides amid what’s already been a deadly wet season.

It only took a week. But, as I told you might happen sooner than later, oil prices surged past $100 per barrel for the first time since 2022 as the war against Iran continues. The latest hit to the global market came when Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates started cutting production over the weekend at key oil fields as shipments through the Strait of Hormuz ground to a halt. In a post on his Truth Social network, President Donald Trump said prices “will drop rapidly when the destruction of the Iran nuclear threat is over,” calling the rise “a very small price to pay for U.S.A.” In response, oil analyst Rory Johnston said Trump’s statement would only spur on the market craziness. “No one who has any idea how the oil market works is buying it — all this does is make it seem like Trump believes it, which means the base case length of this disruption is growing ever-longer,” he wrote. “Tick. Tock.”

The war’s effect on energy markets isn’t just an oil story. As Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote, it’s also a natural gas story. Similarly, as Matthew wrote last week, the winners of the market chaos run the gamut from coal to solar panels.

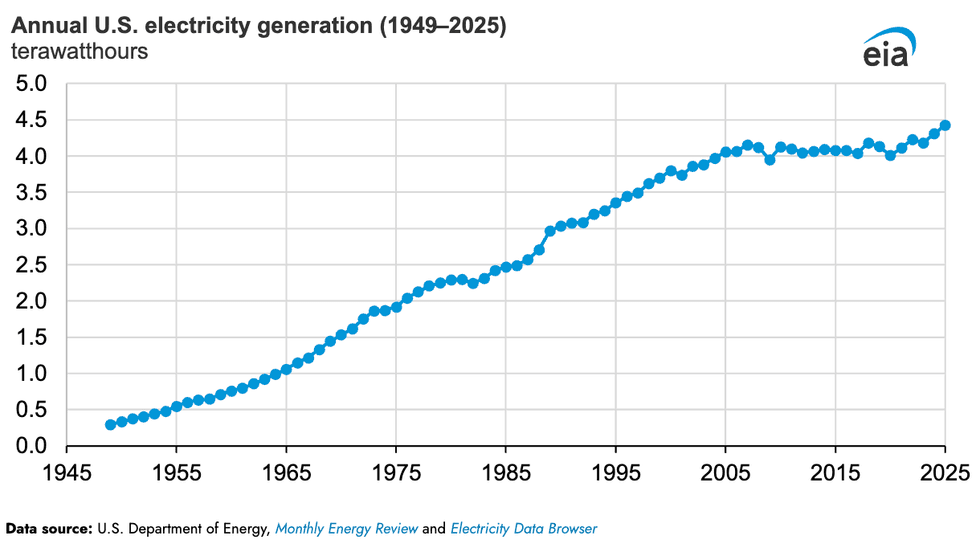

The numbers are in. Last year, the United States generated 4,430 terawatt-hours of electricity. That’s up 2.8% from 2024, which previously had been the highest annual total in the Energy Information Administration’s record books, which date back to 1949. Residential electricity sales grew 2.2%, while commercial surged by 2.9% and industrial rose by just 0.7%.

France produced a record 521.1 terawatt-hours of low-carbon electricity in 2025 as upgrades to existing nuclear reactors allowed the fleet to produce more power, according to data from the grid operator RTE. The latest report is not yet public on RTE’s website, but NucNet reviewed the findings. The electricity mix has largely remained steady for the last two years. France first achieved a 95% low-carbon grid back in 2024, RTE data shows.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

Qcells has resumed solar panel assembly at its plant in Cartersville, Georgia, following a series of delays. By the end of this year, the South Korean-owned company said it plans to add the capacity to pump out 3.3 gigawatts of ingots, wafers, and cells per year. “We are proud to be back to work manufacturing the American-made energy the country needs right now,” Marta Stoepker, head of communications at Qcells, said in a statement. “Like any company, hurdles have and will occur, which requires us to adapt and be nimble, but our overall goal remains the same — to build a complete American solar supply chain.” The moves comes as MAGA warms to solar power as part of a broader “renewables thaw” that Heatmap’s Jael Holzman reported is part of a legal strategy.

Roughly two hours away, SK Battery America laid off nearly 1,000 workers at its factory northeast of Atlanta as automakers cool on electric vehicles. Friday marked the last working day for 958 employees, according to a federal filing the Associated Press reviewed.

A wave energy startup hoping to harness one of the trickier sources of renewable power just broke a record with its latest pilot project. Last month, Eco Wave Power deployed its EWP-EDF One technology Jaffa Port in Israel. The pilot test lasted nine days last month under moderate conditions with daily average wave heights between one and two meters. Throughout the test, the project generated about 2,000 kilowatthours of electricity. “Not only did we continue stable production during moderate wave conditions, but we also experienced the highest waves recorded at our site to date,” Inna Braverman, Eco Wave Power’s chief executive, said in a statement to the trade publication Offshore Energy. “Achieving record average and peak power production during 3-meter wave events provides meaningful validation of our technology’s performance potential as we scale toward commercial projects.”

Scientists discovered a molecular trick used by a unique group of plants to convert sunlight into food. Hornworts are the only known land plant that possesses internal compartments that concentrate carbon dioxide similarly to algae. A new study by researchers at the Boyce Thompson Institute, Cornell University, and the University of Edinburgh suggests that genes from the plants could be used to breed more resistant crops such as wheat. “This research shows that nature has already tested solutions we can learn from,” said Fay-Wei Li, a co-author of the study, said in a statement. “Our job is to understand those solutions well enough to apply them where they're needed most — in the crops that feed the world.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct the added manufacturing capacity at Qcells’ Cartersville plant.

Much of the world is once again asking whether fossil fuels are as reliable as they thought — not because power plants are tripping off or wellheads are freezing up, but because terawatts’ worth of energy are currently stuck outside the Strait of Hormuz in oil tankers and liquified natural gas carriers.

The current crisis in many ways echoes the 2022 energy cataclysm, kicked off when Russia invaded Ukraine. Then, oil, gas, and commodity prices immediately spiked across the globe, forcing Europe to reorient its energy supplies away from Russian gas and leaving developing countries in a state of energy poverty as they could not afford to import suddenly dear fuels.

“It just shows once again the risk of being dependent on imported fossil fuels, whether it’s oil, gas, LNG, or coal. It’s an incredibly fragile system that most of the world depends on,” Nick Hedley, an energy transition research analyst at Zero Carbon Analytics, told me. “Most people are at risk from these shocks.”

Countries suddenly competing once again for scarce gas and oil will have to make tough decisions about their energy systems, with consequences for both their economies and the global climate. In the short run, it is likely that many countries will make a dash for energy security and seek to keep their existing systems running, either paying a premium for LNG or turning to coal. In the long run, however, this moment of energy scarcity could provide yet another reason to turn towards renewables and electrification using solar panels and batteries.

The immediate economic risks may be most intense to Iran’s east.

About 90% of LNG from Qatar goes to Asia, with Qatar serving as essentially the sole supplier of LNG to some countries. Even if there’s more LNG available from non-Qatari sources, many poorer Asian countries are likely to lose out to richer countries in Europe or East Asia that can outbid them for the cargoes.

For countries like Pakistan and Bangladesh, “The result is demand destruction, not aggressive spot purchasing,” according to Kpler, the trade analytics service.

LNG supply is “critical” for Asia — roughly a fifth of Asia’s power can be traced back to LNG from the Middle East, Morgan Stanley analysts wrote in a note to clients Thursday.

In its absence, coal usage will likely tick up in the power sector, leading to declining air quality locally and higher emissions of greenhouse gases globally. “For uninterrupted power, coal remains the key alternative to LNG and there is flex capacity available in South Asia, which has seen new coal plants open,” the Morgan Stanley analysts wrote.

In India, the government is considering implementing an emergency directive to coal-fired power plants to “boost generation and to plan fuel procurement to meet peak summer demand,” sources told Argus Media.

Anne-Sophie Corbeau, global research scholar at the Columbia University Center on Global Energy Policy, told me that she does “expect to see some coal switching,” and that she has “already seen an increase in coal prices.” Benchmarks have already risen to their highest level in at least two years, according to the Financial Times.

This likely coal surge comes as two of the world’s most coal-hungry economies — namely India and China — saw their electricity generation from coal power drop in 2025, the first time that’s happened in both countries at once in around 50 years, according to an analysis by Lauri Myllyvirta of the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air. In much of the rich world, by contrast, coal consumption has been falling for decades.

At the same time energy insecurity may tempt countries to stoke their coal fleet, the past few years have also offered examples of huge deployments of solar in some of the countries most affected by high fossil fuel prices, leading some energy analysts to be guardedly optimistic about how the world could respond to the latest energy crisis.

In the developing world especially, the need to import oil for gasoline and natural gas for electricity generation weighs on the terms of trade. Countries become desperate to export goods in exchange for hard currency to pay for essential fuel imports, which are then often subsidized for consumers, weighing on government budgets. But at least for electricity and transportation, there are increasingly alternatives to expensive, imported fossil fuels.

“This is the first oil and gas crisis-slash-pricing scare in which clean alternatives to oil and gas are fully price-competitive,” Isaac Levi, an analyst at CREA, told me. “Looking at the solar booms, we can expect this to boost clean energy deployment in a major way, and that will be the more significant and durable impact.”

The most cited example for this kind of rapid emergency solar uptake is Pakistan, which has experienced one of the fastest solar conversions in history and expects this year to see a fifth of its electricity come from solar, according to the World Resources Institute.

The country was already under pressure from the rising price of energy following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, when it was forced to hike fuel and power prices and cut subsidies as part of a deal with the International Monetary Fund. From 2021 to 2024, Pakistan’s share of generation from solar more than tripled thanks to the growing glut of inexpensive Chinese solar panels that were locked out of the rich world — especially the United States — by tariffs.

“Countries which are heavily dependent on fossil fuel imports are once more feeling very nervous,” Kingsmill Bond, an energy strategist at the clean energy think tank Ember, told me. “The interesting thing is we have two answers: renewables and electrification. If you want quick results, you put solar panels up quickly.”

Other examples of fast transitions have been in transportation, particularly electric cars.

Ethiopia banned the import of internal combustion vehicles due to worries about the high costs of oil imports and fuel subsidies. EVs make up some 8% of the cars on the road in the East African country, up from virtually zero a few years ago. In Asia, Nepal executed a similar push-pull as part of a government effort to reduce both imports and smog; about five years later, over three-quarters of new car sales in the country were electric.

But getting all the ducks in a row for a green transition has proven difficult in both the rich world and the developing world. Few countries have been able to electrify their economies while also powering them cheaply and cleanly. Ethiopia and Nepal are two examples of electrifying demand for power, particularly transportation. But while the two countries are poor compared to much of the world, they are rich in water and elevation, giving them plentiful firm, non-carbon-emitting electricity generation.

Pakistan, on the other hand, is far from being able to, say, synthesize fertilizers at scale with renewable power. In addition to being a power source, natural gas is also a crucial input in industrial fertilizer manufacturing. Faced with spiking costs, fertilizer plants in Pakistan are shutting down, imperiling future food supplies. All the cheap Chinese solar panels and BYD cars in the world can’t feed a chemical plant.

What remains to be seen is whether this crisis will be severe and enduring enough to lead to a fundamental rethinking about the global energy supply — what kind of energy countries want and where they will get it.

“Energy security crises produce the same structural response: the search for sources that do not require crossing borders and global chokepoints,” Jeff Currie, a longtime commodities analyst, and James Stavridis, a retired admiral and NATO’s former Supreme Allied Commander, argued in an analysis for The Carlyle Group. “Solar, wind, and nuclear are children of the 1970s oil shocks — with growth driven by security, not environmentalism.”

While the United States is not unaffected by the unfolding energy crisis — gasoline prices have spiked over $0.25 per gallon in the past week, and diesel prices have spiked $0.40 — its resilience comes from both its domestic oil and gas production and its solar, wind, and nuclear fleets. Much of this electricity generation and power production can be traced back in some respect to those 1970s oil shocks.

In 2024, the United States imported 17% of its primary energy supply, according to the Energy Information Administration, compared to a peak of 34% in 2006 and the lowest since 1985. Today, Asia still imports 35%, and Europe 60%, Bond told me.

“That’s massive levels of dependency in a fragile world,” Bond said. “It’s a question of security.”