You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

And four more things we learned from Tesla’s Q1 earnings call.

Tesla doesn’t want to talk about its cars — or at least, not about the cars that have steering wheels and human drivers.

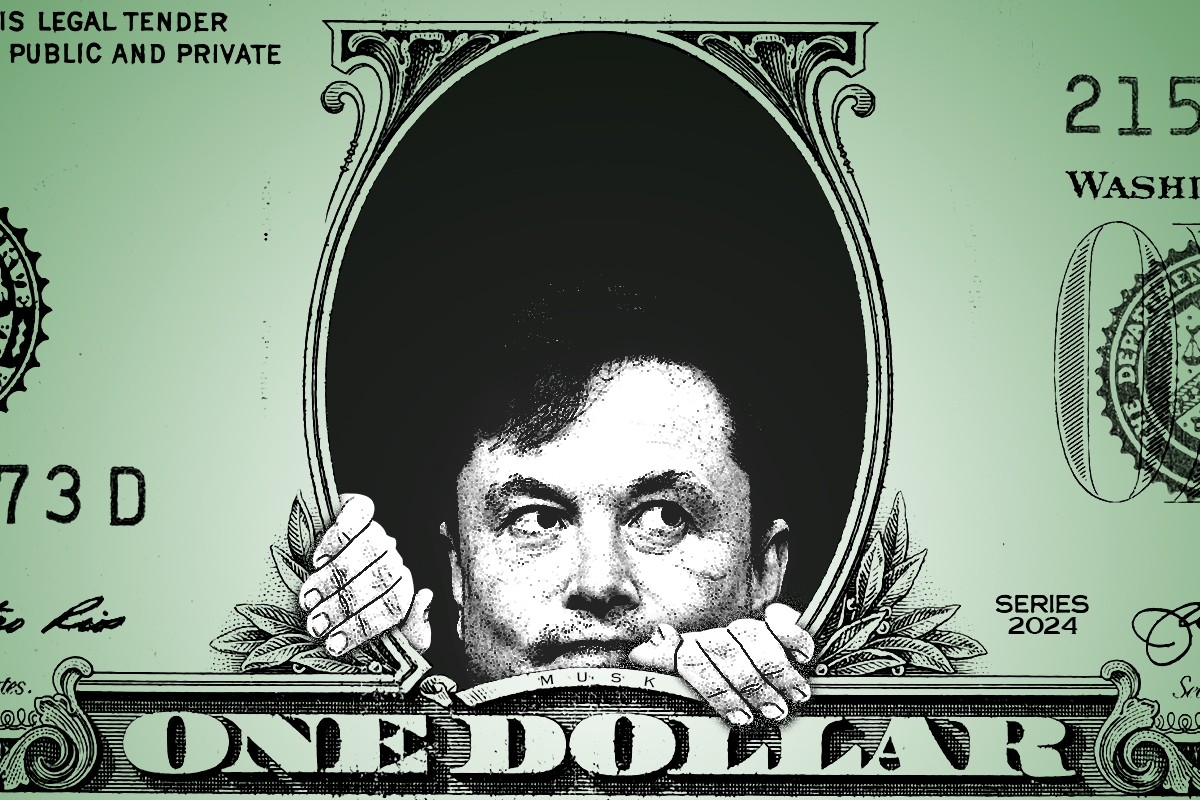

Despite weeks of reports about Tesla’s manufacturing and sales woes — price cuts, recalls, and whether a new, cheaper model would ever come to fruition — CEO Elon Musk and other Tesla executives devoted their quarterly earnings call largely to the company's autonomous driving software. Musk promised that the long-awaited program would revolutionize the auto industry (“We’re putting the actual ‘auto’ in automobile,” as he put it) and lead to the “biggest asset appreciation in history” as existing Tesla vehicles got progressively better self-driving capabilities.

In other Tesla news, car sales are falling, and a new, cheaper vehicle will not be constructed on an all-new platform and manufacturing line, which would instead by reserved for a from-the-ground-up autonomous vehicle.

Here are five big takeaways from the company's earnings and conference call.

The company reported that its “total automotive revenues” came in at $17.4 billion in the first quarter, down 13% from a year ago. Its overall revenues of $21.3 billion, meanwhile, were down 9% from a year ago. The earnings announcement included a number of explanations for the slowdown, which was even worse than Wall Street analysts had expected.

Among the reasons Tesla cited for the disappointing results were arson at its Berlin factory, the obstruction to Red Sea shipping due to Houthi attacks from Yemen, plus a global slowdown in electric vehicle sales “as many carmakers prioritize hybrids over EVs.” The combined effects of these unfortunate events led the company to undertake a well-publicized series of price cuts and other sweeteners for buyers, which dug further into Tesla’s bottom line. Tesla’s chief financial officer, Vaibhav Taneja, said that the company’s free cash flow was negative more than $2 billion, largely due to a “mismatch” between its manufacturing and actual sales, which led to a buildup of car inventory.

The bad news was largely expected — the company’s shares had fallen 40% so far this year leading up to the first quarter earnings, and the past few weeks have featured a steady drumbeat of bad news from the automaker, including layoffs and a major recall. The company’s profits of $1.1 billion were down by more than 50%, short of Wall Street’s expectations — and yet still, Tesla shares were up more than 10% in after-hours trading following the shareholder update and earnings call.

The strange thing about Tesla is that it makes the overwhelming majority of its money from selling cars, but has become the world’s most valuable car company thanks to investors thinking that it’s more of an artificial intelligence company. It’s not uncommon for Tesla CEO Elon Musk and his executives to start talking about their Full Self-Driving technology and autonomous driving goals when the company’s existing business has hit a rough patch, and today was no exception.

Tesla’s value per share was about 33 times its earnings per share by the end of trading on Monday, comparable to how investors evaluate software companies that they expect to grow quickly and expand profitability in the future. Car companies, on the other hand, tend to have much lower valuations compared to their earnings — Ford’s multiple is 12, for instance, and GM’s is 6.

Musk addressed this gap directly on the company’s earnings call. He said that Tesla “should be thought of as an AI/robotics company,” and that “if you value Tesla as an auto company, that’s the wrong framework.” To emphasize just how much the company is pivoting around its self-driving technology, Musk said that “if somebody believes Tesla is not going to solve autonomy they should not be an investor in the company.”

One reason investors value Tesla so differently relative to its peers is that they do, actually, expect the company will make a lot of money using artificial intelligence. No doubt with that in mind, executives made sure to let everyone know that its artificial intelligence spending was immense: The company’s free cash flow may have been negative more than $2 billion, but $1 billion of that was in spending on AI infrastructure. The company also said that it had “increased AI training compute by more than 130%” in the first quarter.

“The future is not only electric, but also autonomous,” the company’s investor update said. “We believe scaled autonomy is only possible with data from millions of vehicles and an immense AI training cluster. We have, and continue to expand, both.”

Musk described the company’s FSD 12 self-driving software as “profound” and said that “it’s only a matter of time before we exceed the reliability of humans, and not much time at that.”

The biggest open question about Tesla is what would happen with its long-promised Model 2, a sub-$30,000 EV that would, in theory, have mass appeal. Reuters reported that the project had been cancelled and that Tesla was instead devoting its resources to another long-promised project, a self-driving ride-hailing vehicle called the “robotaxi.”

Musk tweeted that Reuters was “lying” but never directly denied the report or identified what was wrong with it, instead saying that the robotaxi would be unveiled in August. He later followed up to say that “going balls to the wall for autonomy is a blindingly obvious move. Everything else is like variations on a horse carriage.”

Before the call, Wall Street analysts were begging for a confirmation that newer, cheaper models besides a robotaxi were coming.

“If Tesla does not come out with a Model 2 the next 12 to 18 months, the second growth wave will not come,” Wedbush Securities analyst Dan Ives wrote in a note last week. “Musk needs to recommit to the Model 2 strategy ALONG with robotaxis but it CANNOT be solely replaced by autonomy.”

Anyone who expected to get their answers on today’s call, though, was likely kidding themselves.

Tesla announced today it had updated its planned vehicle line-up to “accelerate the launch of new models ahead of our previously communicated start of production in the second half of 2025,” and that “these new vehicles, including more affordable models, will utilize aspects of the next generation platform as well as aspects of our current platforms.” Musk added on the company’s earnings call that a new model would not be “contingent on any new factory or massive new production line.”

Some analysts attributed the share pricing popping after hours to this line, although it’s unclear just how new this new car would be.

Tesla’s shareholder update indicated that any new, cheaper vehicle would not necessarily be entirely new nor unlock massive new savings through an all-new production process. “This update may result in achieving less cost reduction than previously expected but enables us to prudently grow our vehicle volumes in a more capex efficient manner during uncertain times,” the update said.

Of the robotaxi, meanwhile, the company said it will “continue to pursue a revolutionary ‘unboxed’ manufacturing strategy,” indicating that just the ride-hailing vehicle would be built entirely on a new platform.

Musk also discussed how a robotaxi network could work, saying that it would be a combination of Tesla-operated robotaxis and owners putting their own cars into the ride-hailing fleet. When asked directly about its schedule for a $25,000 car, Musk quickly pivoted to discussing autonomy, saying that when Teslas are able to self-drive without supervision, it will be “the biggest asset appreciation in history,” as existing Teslas became self-driving.

When asked whether any new vehicles would “tweaks” or “new models,” Musk dodged the question, saying that they had said everything they had planned to say on the new cars.

One bright spot on the company’s numbers was the growth in its sales of energy systems, which are tilting more and more toward the company’s battery offerings.

Tesla said it deployed just over 4 gigawatts of energy storage in the first quarter of the year, and that its energy revenue was up 7% from a year ago. Profits from the business more than doubled.

Tesla’s energy business is growing faster than its car business, and Musk said it will continue to grow “significantly faster than the car business” going forward.

Revenues from “services and others,” which includes the company’s charging network, was up by a quarter, as more and more other electric vehicle manufacturers adopt Tesla’s charging standard.

Another speculative Tesla project is Optimus, which the company describes as a “general purpose, bi-pedal, humanoid robot capable of performing tasks that are unsafe, repetitive or boring.” Like many robotics projects, the most the public has seen of Optimus has been intriguing video content, but Musk said that it was doing “factory tasks in the lab” and that it would be in “limited production” in a factory doing “useful tasks” by the end of this year. External sales could begin “by the end of next year,” Musk said.

But as with any new Tesla project, these dates may be aspirational. Musk described them as “just guesses,” but also said that Optimus could “be more valuable than everything else combined.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

The attacks on Iran have not redounded to renewables’ benefit. Here are three reasons why.

The fragility of the global fossil fuel complex has been put on full display. The Strait of Hormuz has been effectively closed, causing a shock to oil and natural gas prices, putting fuel supplies from Incheon to Karachi at risk. American drivers are already paying more at the pump, despite the United States’s much-vaunted energy independence. Never has the case for a transition to renewable energy been more urgent, clear, and necessary.

So despite the stock market overall being down, clean energy companies’ shares are soaring, right?

Wrong.

First Solar: down over 1% on the day. Enphase: down over 3%. Sunrun: down almost 8%; Tesla: down around 2.5%.

Why the slump? There are a few big reasons:

Several analysts described the market action today as “risk-off,” where traders sell almost anything to raise cash. Even safe haven assets like U.S. Treasuries sold off earlier today while the U.S. dollar strengthened.

“A lot of things that worked well recently, they’re taking a big beating,” Gautam Jain, a senior research scholar at the Columbia University Center on Global Energy Policy, told me. “It’s mostly risk aversion.”

Several trackers of clean energy stocks, including the S&P Global Clean Energy Transition Index (down 3% today) or the iShares Global Clean Energy ETF (down over 3%) have actually outperformed the broader market so far this year, making them potentially attractive to sell off for cash.

And some clean energy stocks are just volatile and tend to magnify broader market movements. The iShares Global Clean Energy ETF has a beta — a measure of how a stock’s movements compare with the overall market — higher than 1, which means it has tended to move more than the market up or down.

Then there’s the actual news. After President Trump announced Tuesday afternoon that the United States Development Finance Corporation would be insuring maritime trade “for a very reasonable price,” and that “if necessary” the U.S. would escort ships through the Strait of Hormuz, the overall market picked up slightly and oil prices dropped.

It’s often said that what makes renewables so special is that they don’t rely on fuel. The sun or the wind can’t be trapped in a Middle Eastern strait because insurers refuse to cover the boats it arrives on.

But what renewables do need is cash. The overwhelming share of the lifetime expense of a renewable project is upfront capital expenditure, not ongoing operational expenditures like fuel. This makes renewables very sensitive to interest rates because they rely on borrowed money to get built. If snarled supply chains translate to higher inflation, that could send interest rates higher, or at the very least delay expected interest rate cuts from central banks.

Sustained inflation due to high energy prices “likely pushes interest rate cuts out,” Jain told me, which means higher costs for renewables projects.

While in the long run it may make sense to respond to an oil or natural gas supply shock by diversifying your energy supply into renewables, political leaders often opt to try to maintain stability, even if it’s very expensive.

“The moment you start thinking about energy security, renewables jump up as a priority,” Jain said. “Most countries realize how important it is to be independent of the global supply chain. In the long term it works in favor of renewables. The problem is the short term.”

In the short term, governments often try to mitigate spiking fuel prices by subsidizing fossil fuels and locking in supply contracts to reinforce their countries’ energy supplies. Renewables may thereby lose out on investment that might more logically flow their way.

The other issue is that the same fractured supply chain that drives up oil and gas prices also affects renewables, which are still often dependent on imports for components. “Freight costs go up,” Jain said. “That impacts clean energy industry more.”

As for the Strait of Hormuz, Trump said the Navy would start escorting ships “as soon as possible.”

“It is difficult to imagine more arbitrary and capricious decisionmaking than that at issue here.”

A federal court shot down President Trump’s attempt to kill New York City’s congestion pricing program on Tuesday, allowing the city’s $9 toll on cars entering downtown Manhattan during peak hours to remain in effect.

Judge Lewis Liman of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York ruled that the Trump administration’s termination of the program was illegal, writing, “It is difficult to imagine more arbitrary and capricious decisionmaking than that at issue here.”

So concludes a fight that began almost exactly one year ago, just after Trump returned to the White House. On February 19, 2025, the newly minted Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy sent a letter to Kathy Hochul, the governor of New York, rescinding the federal government’s approval of the congestion pricing fee. President Trump had expressed concerns about the program, Duffy said, leading his department to review its agreement with the state and determine that the program did not adhere to the federal statute under which it was approved.

Duffy argued that the city was not allowed to cordon off part of the city and not provide any toll-free options for drivers to enter it. He also asserted that the program had to be designed solely to relieve congestion — and that New York’s explicit secondary goal of raising money to improve public transit was a violation.

Trump, meanwhile, likened himself to a monarch who had risen to power just in time to rescue New Yorkers from tyranny. That same day, the White House posted an image to social media of Trump standing in front of the New York City skyline donning a gold crown, with the caption, "CONGESTION PRICING IS DEAD. Manhattan, and all of New York, is SAVED. LONG LIVE THE KING!"

New York had only just launched the tolling program a month earlier after nearly 20 years of deliberation — or, as reporter and Hell Gate cofounder Christopher Robbins put it in his account of those years for Heatmap, “procrastination.” The program was supposed to go into effect months earlier before, at the last minute, Hochul tried to delay the program indefinitely, claiming it was too much of a burden on New Yorkers’ wallets. She ultimately allowed congestion pricing to proceed with the fee reduced from $15 during peak hours to $9, and thereafter became one of its champions. The state immediately challenged Duffy’s termination order in court and defied the agency’s instruction to shut down the program, keeping the toll in place for the entirety of the court case.

In May, Judge Liman issued a preliminary injunction prohibiting the DOT from terminating the agreement, noting that New York was likely to succeed in demonstrating that Duffy had exceeded his authority in rescinding it.

After the first full year the program was operating, the state reported 27 million fewer vehicles entering lower Manhattan and a 7% boost to transit ridership. Bus speeds were also up, traffic noise complaints were down, and the program raised $550 million in net revenue.

The final court order issued Tuesday rejected Duffy’s initial arguments for terminating the program, as well as additional justifications he supplied later in the case.

“We disagree with the court’s ruling,” a spokesperson for the Transportation Department told me, adding that congestion pricing imposes a “massive tax on every New Yorker” and has “made federally funded roads inaccessible to commuters without providing a toll-free alternative.” The Department is “reviewing all legal options — including an appeal — with the Justice Department,” they said.

Current conditions: A cluster of thunderstorms is moving northeast across the middle of the United States, from San Antonio to Cincinnati • Thailand’s disaster agency has put 62 provinces, including Bangkok, on alert for severe summer storms through the end of the week • The American Samoan capital of Pago Pago is in the midst of days of intense thunderstorms.

We are only four days into the bombing campaign the United States and Israel began Saturday in a bid to topple the Islamic Republic’s regime. Oil prices closed Monday nearly 9% higher than where trading started last Friday. Natural gas prices, meanwhile, spiked by 5% in the U.S. and 45% in Europe after Qatar announced a halt to shipments of liquified natural gas through the Strait of Hormuz, which tapers at its narrowest point to just 20 miles between the shores of Iran and the United Arab Emirates. It’s a sign that the war “isn’t just an oil story,” Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote yesterday. Like any good tale, it has some irony: “The one U.S. natural gas export project scheduled to start up soon is, of all things, a QatarEnergy-ExxonMobil joint venture.” Heatmap’s Robinson Meyer further explored the LNG angle with Eurasia Group analyst Gregory Brew on the latest episode of Shift Key.

At least for now, the bombing of Iranian nuclear enrichment sites hasn’t led to any detectable increase in radiation levels in countries bordering Iran, the International Atomic Energy Agency said Monday. That includes the Bushehr nuclear power plant, the Tehran research reactor, and other facilities. “So far, no elevation of radiation levels above the usual background levels has been detected in countries bordering Iran,” Director General Rafael Grossi said in a statement.

Financial giants are once again buying a utility in a bet on electricity growth. A consortium led by BlackRock subsidiary Global Infrastructure Partners and Swedish private equity heavyweight EQT announced a deal Monday to buy utility giant AES Corp. The acquisition was valued at more than $33 billion and is expected to close by early next year at the latest. “AES is a leader in competitive generation,” Bayo Ogunlesi, the chief executive officer of BlackRock’s Global Infrastructure Partners, said in a statement. “At a time in which there is a need for significant investments in new capacity in electricity generation, transmission, and distribution, especially in the United States of America, we look forward to utilizing GIP’s experience in energy infrastructure investing, as well as our operational capabilities to help accelerate AES’ commitment to serve the market needs for affordable, safe and reliable power.” The move comes almost exactly a year after the infrastructure divisions at Blackstone, the world’s largest alternative asset manager, bought the Albuquerque-based utility TXNM Energy in an $11.5 billion gamble on surging power demand.

China’s output of solar power surpassed that of wind for the first time last year as cheap panels flooded the market at home and abroad. The country produced nearly 1.2 million gigawatt-hours of electricity from solar power in 2025, up 40% from a year earlier, according to a Bloomberg analysis of National Bureau of Statistics data published Saturday. Wind generation increased just 13% to more than 1.1 gigawatt-hours. The solar boom comes as Beijing bolsters spending on green industry across the board. China went from spending virtually nothing on fusion energy development to investing more in one year than the entire rest of the world combined, as I have previously reported. To some, China is — despite its continued heavy use of coal — a climate hero, as Heatmap’s Katie Brigham has written.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

Canada and India have a longstanding special friendship on nuclear power. Both countries — two of the juggernauts of the 56-country Commonwealth of Nations — operate fleets that rely heavily on pressurized heavy water reactors, a very different design than the light water reactors that make up the vast majority of the fleets in Europe and the United States. Ottawa helped New Delhi build its first nuclear plants. Now the two countries have renewed their atomic ties in what the BBC called a “landmark” deal Monday. As part of the pact, India signed a nine-year agreement with Canada’s largest uranium miner, Cameco, to supply fuel to New Delhi’s growing fleet of seven nuclear plants. The $1.9 billion deal opens a new market for Canada’s expanding production of uranium ore and gives India, which has long worried about its lack of domestic deposits, a stable supply of fuel.

India, meanwhile, is charging ahead with two new reactors at the Kaiga atomic power station in the southwestern state of Karnataka. The units are set to be IPHWR-700, natively designed pressurized heavy water reactors. Last week, the Nuclear Power Corporation of India poured the first concrete on the new pair of reactors, NucNet reported Monday.

The Spanish refiner Moeve has decided to move forward with an investment into building what Hydrogen Insight called “a scaled-back version” of the first phase of its giant 2-gigawatt Andalusian Green Hydrogen Valley project. Even in a less ambitious form, Reuters pegged the total value of the project at $1.2 billion. Meanwhile in the U.S., as I wrote yesterday, is losing major projects right as big production facilities planned before Trump returned to office come online.

Speaking of building, the LEGO Group is investing another $2.8 million into carbon dioxide removal. The Danish toymaker had already pumped money into carbon-removal projects overseen by Climate Impact Partners and ClimeFi. At this point, LEGO has committed $8.5 million to sucking planet-heating carbon out of the atmosphere, where it circulates for centuries. “As the program expands, it is helping to strengthen our understanding of different approaches and inform future decision-making on how carbon removal may complement our wider climate goals,” Annette Stube, LEGO’s chief sustainability officer, told Carbon Herald.