You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

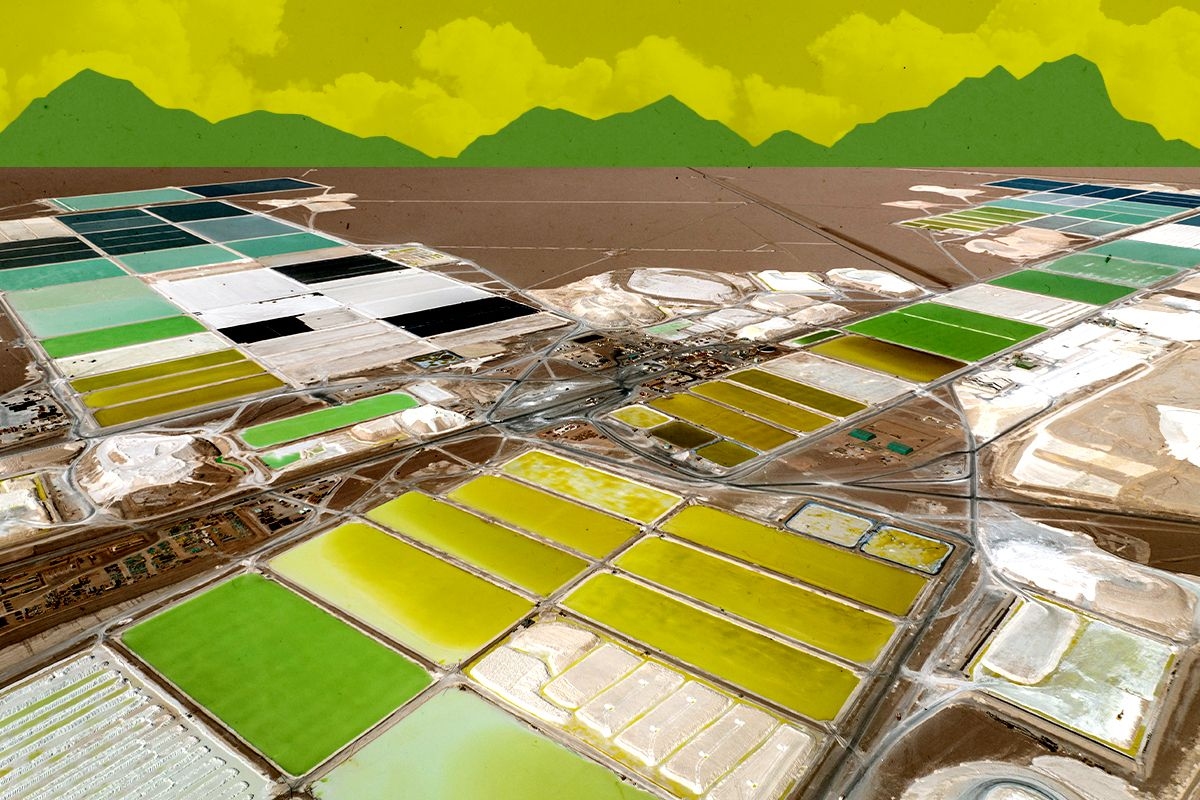

Thea Riofrancos, a professor of political science at Providence College, discusses her new book, Extraction, and the global consequences of our growing need for lithium.

We cannot hope to halt or even slow dangerous climate change without remaking our energy systems, and we cannot remake our energy systems without environmentally damaging projects like lithium mines.

This is the perplexing paradox at the heart of Extraction: The Frontiers of Green Capitalism, a new book by political scientist and climate activist Thea Riofrancos, coming out September 23, from Norton.

Riofrancos, a professor at Providence College, has spent much of her academic career studying mining and oil production in Latin America. In Extraction, she traces the lithium boom of the past five or so years, as the aims of the Global North and Global South began to resemble an inverted mirror. Countries in the latter group that have long been sites of mineral extraction — with little economic benefit — are now seeking to manufacture the more lucrative high tech products further down the supply chain. Meanwhile, after decades of offshoring, Europe and the U.S. suddenly want to bring mining back home in pursuit of “green dominance,” she writes. All of this is happening against the backdrop of China’s geopolitical rise, the war in Ukraine, the COVID-19 pandemic, and worsening effects of climate change.

The book also spends time with the indigenous communities and environmental defenders fighting the lithium industry in Chile, Portugal, and the American West. Riofrancos doesn’t shy away from difficult questions, such as whether there is such a thing as a “right place” for a lithium mine. But she’s optimistic that there’s a better path than the one we’re on now. “The energy transition has presented a fork in the road for the entire economic and social order,” she writes. Down one road, we entrench existing power structures. Down the other, we capitalize on the energy transition to create a more just society.

Green capitalism, Riofrancos argues, is an oxymoron. While we can’t avoid extraction, we can reduce the need for it, for example through better public transit, smaller EV batteries, and minerals recycling, she concludes.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Are there notable differences between lithium and the extraction of other natural resources?

Yes and no. Whether it’s copper or lithium or gold or cobalt — and even I would include hydrocarbons in this, to a degree — whether we look at the economics, the way that they have boom and bust cycles, the fact that governments, even neoliberal governments, tend to take a pretty concerted interest in extractive sectors within their jurisdiction, environmental concerns and direct forms of violence that are meted out at environmental defenders — no, it’s not different. Which should raise alarm bells because a lot of those dynamics are not positive.

What’s different, though, is that precisely because mining companies and host governments claim that the extraction of lithium is urgent and essential for the energy transition, what ends up happening is that these big claims are made — like, “We are now a sustainable mining company because we’re extracting lithium,” or, “This is part of our green industrial policy.” This toxic and dirty extractive sector is now greenified because of its role in the energy transition. On the one hand, that’s greenwashing. On the other, it’s an opening. When companies make those claims, it’s something to hold them accountable to.

I was somewhat surprised by the issues you describe with the way lithium mining is regulated in Chile — the companies do their own environmental monitoring, there’s a lack of transparent data, the brine they mine in the Atacama is not considered water under Chilean law, etc. It seems like the state could change a lot of this. Why hasn’t it?

States in the Global South, although not exclusively there, lack geological and hydrological data about their own territory. In ways that we can trace to colonialism and neocolonialism in terms of who controls the territory and who has knowledge about it, the actors that have the basic data about deposits, how they interact with water sources, all of that, are the companies. And so to even regulate these companies better, you first need to set up independent and objective sources of data collection — and that’s something that any state might struggle with, but especially in the Global South, given the kind of legacy under which these companies operated, with little oversight of the state.

The [U.S. Geological Survey] doesn’t exist everywhere in the world. Not every state has a surveying agency with that level of expertise. And even in the U.S., the USGS actually has quite partial knowledge of what’s here. And there are many examples of companies in the U.S. hiding proprietary knowledge from the government.

What about after Gabriel Boric became president in Chile, in 2022, and created this new public-private partnership between the mining giant SQM and the government. Wouldn’t that have given the Chilean government more visibility and more control?

I think in some ways he’s made strides. He has set aside many salt flats for conservation. A right wing government wouldn’t have done that. He also is inserting the state, via the state-owned copper company Codelco, entering into public-private partnerships with companies, including SQM. If all goes according to plan, that will help the state learn more about lithium extraction, or maybe even set up their own lithium company, which was the initial goal of this government.

I’ll just point out two things to show how this is difficult. According to indigenous communities and environmental activists that have been organizing around this, they were excluded from the initial moment where that memorandum of understanding between SQM and Codelco was signed, and so they felt like it was a reenactment of historic injuries by a government that they had cautiously supported or thought would be different. Now they’re back at the negotiating table and indigenous communities are being consulted again. But there was a critical moment where the MOU was signed and indigenous communities were not present, and actually learned about it from the media. These historic patterns are really hard to change because companies hold a lot of power.

Even a progressive government is balancing indigenous rights and ecological protection with a desire to not lose market share. Argentina is starting to catch up with Chile — is Chile still going to remain the number two producer globally? Does it need to change its regulations to attract more companies? This is the kind of double bind that Global South societies find themselves in.

You write about this tension between expanding extraction and minimizing environmental and community impacts. Do you believe there are actually ways to minimize these impacts?

Absolutely. You can do anything better. I believe in human ingenuity and science and figuring out how to improve processes. There are ways to extract using less water, using a smaller land footprint, using fewer polluting energy sources. One of the reasons emissions from mining are not insignificant is a lot of it happens off-grid, and for now, that means diesel generators or gasoline-powered mining vehicles, let alone the cargo ships that are shipping the stuff around the world. So we could think about localizing or regionalizing supply chains.

The question is, how do we get companies to change their practices? They might do it if a regulator tells them they have to, if civil society puts so much pressure on them that it just becomes reputational harm if they don’t do it, if perhaps activist shareholders ask or tell the company to change its practices.

But the company, if it’s a shareholder-owned company, has one main obligation, which is to maximize the value of their shares. Changing your technological setup and your physical plant arrangement is costly, and it may not immediately produce more profits. And so you have to think about, what are the crude economic dynamics that keep companies on a particular technological path in terms of how they do their physical operations? And then think, using the power of policy, of economics, of consumer pressure, whatever it is, how to get them to make a decision that may not be in their immediate shareholder interest.

One theme in the book is that countries in the West are making a case for domestic mining by arguing that it will be greener than mining in the Global South. Is there any evidence for that? What’s the logic?

This was honestly one of the most surprising things in my research as someone that primarily has worked in Latin America. I heard some rumblings — and this was in 2019, before the pandemic — of EU officials wanting to onshore. It confused me because mining is toxic, it’s low value-added. And what I learned is that it had come to a point where Western policymakers saw the whole supply chain as a domain of geostrategic power.

And then, probably some people really feel this way, and other people are using it as nice rhetoric, but Western policymakers also started to come to the idea that it would be more “responsible” to mine in the West. This is in no small part due to the fact that the mining industry has deservedly gotten a lot of negative coverage for, in some cases, outright killing people. In other cases, you have an avalanche that destroys a village. You have water contamination. There are issues around forced labor, how the Uyghurs are treated in China. So there was a lot of bad press on the industry. I think they thought, We can solve a few problems at once. We can increase our geopolitical power by having domestic supply chains for the most important 21st century technologies, and we can also make the claim to consumers, regulators, and the media that this is better if you care about responsible, ethical, green mining.

The reality is, of course, more complex than that. Our mining law in the U.S. that governs hard rock mining on public lands is from 1872, which tells you everything you need to know. It’s extremely out of date with the modern mining industry and the scale of harm that mining poses, and it also literally was implemented during the westward expansion and dispossession of indigenous peoples to serve that end.

In fact, countries in Latin America tend to have better — on paper — governance of mining than the U.S., though they may not have the state capacity to always implement it. In Europe, there’s even more dependence on imports. A lot of the European countries have almost no regulations on the books for basic things like, how do you deal with mining waste? And so in the Global North, what we have to fight for is a mining governance regime and a set of legal codes and regulations that is up to date.

This book is pretty critical of the way communities have been treated in the lithium boom so far. What are some of the ways community engagement can be done better?

We see better outcomes when communities are organized, when they actually identify as a community, have some meetings, maybe set up a group to coordinate themselves. Like, who’s going to go to the public hearing? Who’s going to contact a lawyer? Who’s going to contact the water expert? Because communities need a lot of outside help. The companies have lawyers, they have experts, they probably have friends in government. A lot of lawyers and experts that companies hire used to work for the government, and they know these processes inside out, and so the community needs to be as or more organized. They’re already on the losing end of a power imbalance.

In a way, none of this is about what companies can do, because I presume that companies are responsive to pressure. Multinationals, insofar as they’re shareholder-owned, their main goal is to maximize value, and that’s it. It’s that simple. And so in order to get them to behave differently towards communities, outside forces need to take a role. The first outside force is the community itself. A second is, how involved is the government? And how objective and public-serving is the government? Where governments take a more objective role and help protect the baseline rights of communities, make sure that those rights are not being violated by companies, help distribute more culturally sensitive and appropriate information about the mine, we could get better outcomes that way.

You had activists tell you, “I support lithium mining, but this is the wrong place for it.” Do you think there is such a thing as a right or wrong place, or even a better or worse place for a lithium mine?

This was honestly the most vexing question that I had to contemplate in my own research. I often think about how these communities are called NIMBYs, and there’s two reasons that’s a really inappropriate term. First of all, the “my backyard” — not every person has private property, or that’s not their stake in the matter. It’s not about, this is going to decrease the value of my property, or this is going to disrupt my ocean view. It’s about the land that they have a deep relationship with.

The second thing is, I don’t think most of the people that call these communities NIMBYs would really want to live next to a large-scale mine, either. They are just enormous scars on the landscape. I understand that they are necessary, to some degree, to provide for the technologies that we enjoy, including life-saving and planet-saving technology. Even in my perfect world, where everyone is riding an electric bus or bike or walking around, some lithium is still needed in the near term. In the future, we could conceivably enter into a circular economy, but we don’t have the level of feedstock for that yet.

So the question remains, where are we going to mine? I don’t have an easy answer to that, but I will say that in the entire process of land use planning, the corporation is the protagonist. In the U.S., a place that I think most political scientists would say has more state capacity than a country in Africa or Latin America, we do not use that capacity to proactively plan land use. I think it would make sense to really rearrange the process such that governments plan with substantial community input, and then corporations, if we want to have private corporations doing this, get the ability to compete for contracts. I know that would be a big lift to change that policy dynamic, but I think we need to have the conversation.

You write a lot about this difficult dance between supply and demand in mining. What are you seeing right now in how the lithium industry is reacting to Trump’s dismantling of EV policy?

With Trump, it’s particularly interesting and bizarre because on the list of fast-tracked mines, you have several lithium mines and some lithium processing along with other “critical minerals.” He really wants to expand mining, to the point that the Pentagon is now the No. 1 investor in our only rare earth mine in the U.S. They bought 15% of MP Materials’ shares, the company that manages the Mountain Pass mine. And so Trump is fast-tracking mines, he’s sending huge amounts of public money to financially underwrite these mining companies. But yet, he’s destroying demand for rare earths. He loves to talk about AI and military tech — that’s a small slice of demand. It’s really about wind turbines and electric vehicle motors. That’s really where the demand is. With lithium, it’s even clearer.

That all seems like a recipe for prices to crash.

The thing is, they already had crashed because of a supply glut. But at the same time, the market will likely pick back up because we’re seeing so much action elsewhere in the world. It’s very easy to focus on the U.S., especially because the U.S. government is such a basket case right now. But if we zoom out, there’s been a bunch of recent reporting, including in Heatmap, on how rapidly the energy transition is going in other parts of the world, with China playing an enormous role not only on the trade side, but also in foreign direct investment, in setting up solar and EV manufacturing hubs in the Global South.

And so I think that Trump can dismantle EVs as much as he wants in the U.S., and that’s a shame given that transportation is our most polluting sector. I mean, that pains me as a climate activist. But the world is bigger than the U.S.

The last thing I’ll say — and this is another interesting contradiction — in the Big, Beautiful Bill, it’s not across the board against all green technologies. There’s this distinction that conservatives increasingly like to make called “clean, firm power.” So they put nuclear, geothermal, and battery storage in that. Now, battery storage, what is that made of? Lithium. So in a weird way, they like lithium mining, they like batteries for storage, they just don’t like electric vehicles. We’re still going to have lithium demand in the U.S., and lots of individual people will still buy electric cars, and blue states will still procure them for their public fleets. He’s not going to kill the market. He’s just going to slow its growth, primarily by making it less affordable for working and middle class people.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

The proportion of voters who strongly oppose development grew by nearly 50%.

During his State of the Union address Tuesday night, President Donald Trump attempted to stanch the public’s bleeding support for building the data centers his administration says are necessary to beat China in the artificial intelligence race. With “many Americans” now “concerned that energy demand from AI data centers could unfairly drive up their electricity bills,” Trump said, he pledged to make major tech companies pay for new power plants to supply electricity to data centers.

New polling from energy intelligence platform Heatmap Pro shows just how dramatically and swiftly American voters are turning against data centers.

Earlier this month, the survey, conducted by Embold Research, reached out to 2,091 registered voters across the country, explaining that “data centers are facilities that house the servers that power the internet, apps, and artificial intelligence” and asking them, “Would you support or oppose a data center being built near where you live?” Just 28% said they would support or strongly support such a facility in their neighborhood, while 52% said they would oppose or strongly oppose it. That’s a net support of -24%.

When Heatmap Pro asked a national sample of voters the same question last fall, net support came out to +2%, with 44% in support and 42% opposed.

The steep drop highlights a phenomenon Heatmap’s Jael Holzman described last fall — that data centers are "swallowing American politics,” as she put it, uniting conservation-minded factions of the left with anti-renewables activists on the right in opposing a common enemy.

The results of this latest Heatmap Pro poll aren’t an outlier, either. Poll after poll shows surging public antipathy toward data centers as populists at both ends of the political spectrum stoke outrage over rising electricity prices and tech giants struggle to coalesce around a single explanation of their impacts on the grid.

“The hyperscalers have fumbled the comms game here,” Emmet Penney, an energy researcher and senior fellow at the right-leaning Foundation for American Innovation, told me.

A historian of the nuclear power sector, Penney sees parallels between the grassroots pushback to data centers and the 20th century movement to stymie construction of atomic power stations across the Western world. In both cases, opponents fixated on and popularized environmental criticisms that were ultimately deemed minor relative to the benefits of the technology — production of radioactive waste in the case of nuclear plants, and as seems increasingly clear, water usage in the case of data centers.

Likewise, opponents to nuclear power saw urgent efforts to build out the technology in the face of Cold War competition with the Soviet Union as more reason for skepticism about safety. Ditto the current rhetoric on China.

Penney said that both data centers and nuclear power stoke a “fear of bigness.”

“Data centers represent a loss of control over everyday life because artificial intelligence means change,” he said. “The same is true about nuclear,” which reached its peak of expansion right as electric appliances such as dishwashers and washing machines were revolutionizing domestic life in American households.

One of the more fascinating findings of the Heatmap Pro poll is a stark urban-rural divide within the Republican Party. Net support for data centers among GOP voters who live in suburbs or cities came out to -8%. Opposition among rural Republicans was twice as deep, at -20%. While rural Democrats and independents showed more skepticism of data centers than their urbanite fellow partisans, the gap was far smaller.

That could represent a challenge for the Trump administration.

“People in the city are used to a certain level of dynamism baked into their lives just by sheer population density,” Penney said. “If you’re in a rural place, any change stands out.”

Senator Bernie Sanders, the democratic socialist from Vermont, has championed legislation to place a temporary ban on new data centers. Such a move would not be without precedent; Ireland, transformed by tax-haven policies over the past two decades into a hub for Silicon Valley’s giants, only just ended its de facto three-year moratorium on hooking up data centers to the grid.

Senator Josh Hawley, the Missouri Republican firebrand, proposed his own bill that would force data centers off the grid by requiring the complexes to build their own power plants, much as Trump is now promoting.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, you have Republicans such as Mississippi Governor Tate Reeves, who on Tuesday compared halting construction of data centers to “civilizational suicide.”

“I am tempted to sit back and let other states fritter away the generational chance to build. To laugh at their short-sightedness,” he wrote in a post on X. “But the best path for all of us would be to see America dominate, because our foes are not like us. They don’t believe in order, except brutal order under their heels. They don’t believe in prosperity, except for that gained through fraud and plunder. They don’t think or act in a way I can respect as an American.”

Then you have the actual hyperscalers taking opposite tacks. Amazon Web Services, for example, is playing offense, promoting research that shows its data centers are not increasing electricity rates. Claude-maker Anthropic, meanwhile, issued a de facto mea culpa, pledging earlier this month to offset all its electricity use.

Amid that scattershot messaging, the critical rhetoric appears to be striking its targets. Whether Trump’s efforts to curb data centers’ impact on the grid or Reeves’ stirring call to patriotic sacrifice can reverse cratering support for the buildout remains to be seen. The clock is ticking. There are just 36 weeks until the midterm Election Day.

The public-private project aims to help realize the president’s goal of building 10 new reactors by 2030.

The Department of Energy and the Westinghouse Electric Company have begun meeting with utilities and nuclear developers as part of a new project aimed at spurring the country’s largest buildout of new nuclear power plants in more than 30 years, according to two people who have been briefed on the plans.

The discussions suggest that the Trump administration’s ambitious plans to build a fleet of new nuclear reactors are moving forward at least in part through the Energy Department. President Trump set a goal last year of placing 10 new reactors under construction nationwide by 2030.

The project aims to purchase the parts for 8 gigawatts to 10 gigawatts of new nuclear reactors, the people said. The reactors would almost certainly be AP1000s, a third-generation reactor produced by Westinghouse capable of producing up to 1.1 gigawatts of electricity per unit.

The AP1000 is the only third-generation reactor successfully deployed in the United States. Two AP1000 reactors were completed — and powered on — at Plant Vogtle in eastern Georgia earlier this decade. Fifteen other units are operating or under construction worldwide.

Representatives from Westinghouse and the Energy Department did not respond to requests for comment.

The project would use government and private financing to buy advanced reactor equipment that requires particularly long lead times, the people said. It would seek to lower the cost of the reactors by placing what would essentially be a single bulk order for some of their parts, allowing Westinghouse to invest in and scale its production efforts. It could also speed up construction timelines for the plants themselves.

The department is in talks with four to five potential partners, including utilities, independent power producers, and nuclear development companies, about joining the project. Under the plan, these utilities or developers would agree to purchase parts for two new reactors each. The program would be handled in part by the department’s in-house bank, the Loan Programs Office, which the Trump administration has dubbed the Office of Energy Dominance Financing.

This fleet-based approach to nuclear construction has succeeded in the past. After the oil crisis struck France in the 1970s, the national government responded by planning more than three-dozen reactors in roughly a decade, allowing the country to build them quickly and at low cost. France still has some of the world’s lowest-carbon electricity.

By comparison, the United States has built three new nuclear reactors, totaling roughly 3.5 gigawatts of capacity, since the year 2000, and it has not significantly expanded its nuclear fleet since 1990. The Trump administration set a goal in May to quadruple total nuclear energy production — which stands at roughly 100 gigawatts today — to more than 400 gigawatts by the middle of the century.

The Trump administration and congressional Republicans have periodically announced plans to expand the nuclear fleet over the past year, although details on its projects have been scant.

Senator Dave McCormick, a Republican of Pennsylvania, announced at an energy summit last July that Westinghouse was moving forward with plans to build 10 new reactors nationwide by 2030.

In October, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick announced a new deal between the U.S. government, the private equity firm Brookfield Asset Management, and the uranium company Cameco to deploy $80 billion in new Westinghouse reactors across the United States. (A Brookfield subsidiary and Cameco have jointly owned Westinghouse since it went bankrupt in 2017 due to construction cost overruns.) Reuters reported last month that this deal aimed to satisfy the Trump administration’s 2030 goal.

While there have been other Republican attempts to expand the nuclear fleet over the years, rising electricity demand and the boom in artificial intelligence data centers have brought new focus to the issue. This time, Democratic politicians have announced their own plans to boost nuclear power in their states.

In January, New York Governor Kathy Hochul set a goal of building 4 gigawatts of new nuclear power plants in the Empire State.

In his State of the State address, Governor JB Pritzker of Illinois told lawmakers last week that he hopes to see at least 2 gigawatts of new nuclear power capacity operating in his state by 2033.

Meeting Trump’s nuclear ambitions has been a source of contention between federal agencies. Politico reported on Thursday that the Energy Department had spent months negotiating a nuclear strategy with Westinghouse last year when Lutnick inserted himself directly into negotiations with the company. Soon after, the Commerce Department issued an announcement for the $80 billion megadeal, which was big on hype but short on details.

The announcement threw a wrench in the Energy Department’s plans, but the agency now seems to have returned to the table. According to Politico, it is now also “engaging” with GE Hitachi, another provider of advanced nuclear reactors.

On nuclear tax credits, BLM controversy, and a fusion maverick’s fundraise

Current conditions: A third storm could dust New York City and the surrounding area with more snow • Floods and landslides have killed at least 25 people in Brazil’s southeastern state of Minas Gerais • A heat dome in Western Europe is pushing up temperatures in parts of Portugal, Spain, and France as high as 15 degrees Celsius above average.

The Department of Energy’s in-house lender, the Loan Programs Office — dubbed the Office of Energy Dominance Financing by the Trump administration — just gave out the largest loan in its history to Southern Company. The nearly $27 billion loan will “build or upgrade over 16 gigawatts of firm reliable power,” including 5 gigawatts of new gas generation, 6 gigawatts of uprates and license renewals for six different reactors, and more than 1,300 miles of transmission and grid enhancement projects. In total, the package will “deliver $7 billion in electricity cost savings” to millions of ratepayers in Georgia and Alabama by reducing the utility giant’s interest expenses by over $300 million per year. “These loans will not only lower energy costs but also create thousands of jobs and increase grid reliability for the people of Georgia and Alabama,” Secretary of Energy Chris Wright said in a statement.

Over in Utah, meanwhile, the state government is seeking the authority to speed up its own deployment of nuclear reactors as electricity demand surges in the desert state. In a letter to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission dated November 10 — but which E&E News published this week — Tim Davis, the executive director of Utah’s Department of Environmental Quality, requested that the federal agency consider granting the state the power to oversee uranium enrichment, microreactor licensing, fuel storage, and reprocessing on its own. All of those sectors fall under the NRC’s exclusive purview. At least one program at the NRC grants states limited regulatory primacy for some low-level radiological material. While there’s no precedent for a transfer of power as significant as what Utah is requesting, the current administration is upending norms at the NRC more than any other government since the agency’s founding in 1975.

Building a new nuclear plant on a previously undeveloped site is already a steep challenge in electricity markets such as New York, California, or the Midwest, which broke up monopoly utilities in the 1990s and created competitive auctions that make decade-long, multibillion-dollar reactors all but impossible to finance. A growing chorus argues, as Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote, that these markets “are no longer working.” Even in markets with vertically-integrated power companies, the federal tax credits meant to spur construction of new reactors would make financing a greenfield plant is just as impossible, despite federal tax credits meant to spur construction of new reactors. That’s the conclusion of a new analysis by a trio of government finance researchers at the Center for Public Enterprise. The investment tax credit, “large as it is, cannot easily provide them with upfront construction-period support,” the report found. “The ITC is essential to nuclear project economics, but monetizing it during construction poses distinct challenges for nuclear developers that do not arise for renewable energy projects. Absent a public agency’s ability to leverage access to the elective payment of tax credits, it is challenging to see a path forward for attracting sufficient risk capital for a new nuclear project under the current circumstances.”

Steve Pearce, Trump’s pick to lead the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management, wavered when asked about his record of pushing to sell off federal lands during his nomination hearing Wednesday. A former Republican lawmaker from New Mexico, Pearce has faced what the public lands news site Public Domain called “broad backlash from environmental, conservation, and hunting groups for his record of working to undermine public land protections and push land sales as a way to reduce the federal deficit.” Faced with questions from Democratic senators, Pearce said, “I’m not so sure that I’ve changed,” but insisted he didn’t “believe that we’re going to go out and wholesale land from the federal government.” That has, however, been the plan since the start of the administration. As Heatmap’s Jeva Lange wrote last year, Republicans looked poised to use their trifecta to sell off some of the approximately 640 million acres of land the federal government owns.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

At Tuesday’s State of the Union address, as I told you yesterday, Trump vowed to force major data center companies to build, bring, or buy their own power plants to keep the artificial intelligence boom from driving up electricity prices. On Wednesday, Fox News reported that Amazon, Google, Meta, Microsoft, xAI, Oracle, and OpenAI planned to come to the White House to sign onto the deal. The meeting is set to take place sometime next month. Data centers are facing mounting backlash. Developers abandoned at least 25 data centers last year amid mounting pushback from local opponents, Heatmap's Robinson Meyer recently reported.

Shine Technologies is a rare fusion company that’s actually making money today. That’s because the Wisconsin-based firm uses its plasma beam fusion technology to produce isotopes for testing and medical therapies. Next, the company plans to start recycling nuclear waste for fresh reactor fuel. To get there, Shine Technologies has raised $240 million to fund its efforts for the next few years, as I reported this morning in an exclusive for Heatmap. Nearly 63% of the funding came from biotech billionaire Patrick Soon-Shiong, who will join the board. The capital will carry the company through the launch of the world’s largest medical isotope producer and lay the foundations of a new business recycling nuclear waste in the early 2030s that essentially just reorders its existing assembly line.

Vineyard Wind is nearly complete. As of Wednesday, 60 of the project’s 62 turbines have been installed off the coast of Massachusetts. Of those, E&E News reported, 52 have been cleared to start producing power. The developer Iberdrola said the final two turbines may be installed in the next few days. “For me, as an engineer, the farm is already completed,” Iberdrola’s executive chair, Ignacio Sánchez Galán, told analysts on an earnings call. “I think these numbers mean the level of availability is similar for other offshore wind farms we have in operation. So for me, that is completed.”