You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Since July 4, the federal government has escalated its assault on wind development to previously unimaginable heights.

The Trump administration is widening its efforts to restrict wind power, proposing new nationwide land use restrictions and laying what some say is the groundwork for targeting wind facilities under construction or even operation.

Since Trump re-entered the White House, his administration has halted wind energy leasing, stopped approving wind projects on federal land or in federal waters, and blocked wind developers from getting permits for interactions with protected birds, putting operators that harm a bald eagle or endangered hawk at risk of steep federal fines or jail time.

For the most part, however, projects either under construction or already operating have been spared. With a handful of exceptions — the Lava Ridge wind farm in Idaho, the Atlantic Shores development off the coast of New Jersey and the Empire Wind project in the New York Bight — most projects with advanced timelines appeared to be safe.

But that was then. In the past week, a series of Trump administration actions has presented fresh threats to wind developers seeking everyday sign-offs for things that have never before presented a potential problem. Renewables developers and their supporters say the rush of actions is intended to further curtail investment in wind after Congress earlier this summer drastically curtailed tax breaks for wind and solar.

“I don’t think they even care if it’ll stand judicial review,” Erik Schlenker-Goodrich, executive director of the Western Environmental Law Center, told me. “It’s just going to chill anyone with limited capital from going to [an] agency.”

First up: The Transportation Department last Tuesday declared that it would now call for a national 1.2-mile property setback — that is, a mandatory distance requirement — for all wind facilities near railroads and highways.

When it announced the move, the DOT claimed it had “recently discovered” that the Biden administration had “overruled a safety recommendation for dozens of wind energy projects” related to radio frequencies near transportation corridors, suggesting the federal government would soon be stepping in to rectify the purported situation. To try and support this claim, the agency released a pair of Biden-era letters from a DOT spectrum policy office related to Prairie Heritage, a Pattern Energy wind project in Illinois, one recommending action due to radio issues and a subsequent analysis that no longer raised concerns.

Citing these, the DOT stated that political officials had overruled the concerns of safety experts and called on Congress to investigate. It also suggested that “33 projects have been uncovered where the original safety recommendation was rescinded.” DOT couldn’t be reached for comment in time for publication. Pattern Energy declined to comment.

Buried in this announcement was another reveal: DOT said that it would instruct the Federal Aviation Administration to “thoroughly evaluate proposed wind turbines to ensure they do not pose a danger to aviation” — a signal that a once-routine FAA height clearance required for almost every wind turbine could now become a hurdle for the entire sector.

At the same time, the Department of the Interior unveiled a twin set of secretarial orders that went beyond even its edict of just the week before, requiring that all permits for wind and solar go through high-level political screening.

First, also on Tuesday, the department released a mega-order claiming the Biden administration “chose to misapply” the law in approving offshore wind projects and calling on nearly every branch of the agency to review “any regulations, guidance, policies, and practices” related to a host of actions that occur before and after a project receives its final record of decision, including right-of-way authorizations, land use plan amendments and revisions, and environmental and wildlife permit and analyses. Among its many directives, the order instructed Interior staff to prepare a report on fully-approved offshore wind projects that may have impacts on “military readiness.” It also directed the agency’s top lawyer to review all “pending litigation” against a wind or solar project approval and identify cases where the agency could withdraw or rescind it.

Then came Friday. As I scooped for Heatmap, Interior will no longer permit a wind project on federal land if it would produce less energy per acre than a coal, gas, or nuclear facility at the same site. This happens to be a metric where wind typically performs worse than its more conventional counterparts; that being the case, this order could amount to a targeted and de facto ban on wind on federal property.

Taken in sum, it’s difficult not to read this series of orders as a message to the entire wind industry: Avoid the federal government at all costs, if you can help it.

What does the future of wind development look like in the U.S. if you have to work around the feds at every turn? “It’s a good question,” John Hensley, senior vice president for markets and policy analysis at the American Clean Power Association, told me this afternoon. The challenge is that “as we see more and more of these crop up, it becomes more and more difficult to move these projects forward — and, somewhat equally important, it becomes difficult to find the financing to develop these projects.”

“If the financing community is unwilling to take on that risk then the money dries up and these projects have a lower likelihood of happening,” Hensley said, adding: “We haven’t reached the threshold where all activity has ground to a stop, but it certainly has pushed companies to re-evaluate their portfolios and think about where they do have this regulatory risk, and it pushes the financing community to do the same. It’s just putting more barriers in place to move these projects forward.”

Anti-wind activists, meanwhile, see these orders as a map to the anti-renewables Holy Grail: forcibly decommissioning projects that are already in service.

On the same day as the mega-order, the coastal vacation town of Nantucket, Massachusetts, threatened legal action against Vineyard Wind, the offshore wind project that experienced a construction catastrophe during the middle of last year’s high tourist season, sending part of a turbine blade and shards of fiberglass into the waters just offshore. The facility is still partially under construction, but is already sending electrons to the grid. Less than 24 hours later, the Texas Public Policy Foundation, a conservative legal group tied to other lawsuits against offshore wind projects, filed a petition to the Interior Department requesting that it reconsider prior permits for Vineyard Wind and halt operations.

David Stevenson, a former Trump adviser who now works with the offshore wind opponent Caesar Rodney Institute, told me he thinks the Interior order laid out a pathway to reconsider approvals. “Many of us who have been plaintiffs in various lawsuits have suggested to the Secretary of the Interior that there are flaws, and the flaws are spelled out in the lawsuits to the permit process.”

Nick Krakoff, a senior attorney with the pro-climate action Conservation Law Foundation, had an identical view to Stevenson’s. “I’m certainly not aware of this ever being done before,” he told me, noting that the Biden administration paused new oil and gas leases but didn’t do a “systematic review” of a sector to find “ways to potentially undo prior permitting decisions.”

Democrats in Congress have finally started speaking up about this. Last week four Democrats — led by Martin Heinrich, the top Democrat on the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee — sent a letter to Interior Secretary Doug Burgum arguing that the secretarial orders would delay any decision related to renewable energy in general, “no matter how routine.” A Democratic staffer on the committee, who requested anonymity to speak candidly about the letter, told me privately that “fear is where this is headed.”

“They’re just building a record that will ultimately allow them to not approve future projects, and potentially deny projects that have already been approved,” the staffer said. ”They have all these new hoops they have to go through, and if they’re saying these things aren’t in the public interest, it’s not hard to see where they are going.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

1. Marion County, Indiana — State legislators made a U-turn this week in Indiana.

2. Baldwin County, Alabama — Alabamians are fighting a solar project they say was dropped into their laps without adequate warning.

3. Orleans Parish, Louisiana — The Crescent City has closed its doors to data centers, at least until next year.

A conversation with Emily Pritzkow of Wisconsin Building Trades

This week’s conversation is with Emily Pritzkow, executive director for the Wisconsin Building Trades, which represents over 40,000 workers at 15 unions, including the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, the International Union of Operating Engineers, and the Wisconsin Pipe Trades Association. I wanted to speak with her about the kinds of jobs needed to build and maintain data centers and whether they have a big impact on how communities view a project. Our conversation was edited for length and clarity.

So first of all, how do data centers actually drive employment for your members?

From an infrastructure perspective, these are massive hyperscale projects. They require extensive electrical infrastructure and really sophisticated cooling systems, work that will sustain our building trades workforce for years – and beyond, because as you probably see, these facilities often expand. Within the building trades, we see the most work on these projects. Our electricians and almost every other skilled trade you can think of, they’re on site not only building facilities but maintaining them after the fact.

We also view it through the lens of requiring our skilled trades to be there for ongoing maintenance, system upgrades, and emergency repairs.

What’s the access level for these jobs?

If you have a union signatory employer and you work for them, you will need to complete an apprenticeship to get the skills you need, or it can be through the union directly. It’s folks from all ranges of life, whether they’re just graduating from high school or, well, I was recently talking to an office manager who had a 50-year-old apprentice.

These apprenticeship programs are done at our training centers. They’re funded through contributions from our journey workers and from our signatory contractors. We have programs without taxpayer dollars and use our existing workforce to bring on the next generation.

Where’s the interest in these jobs at the moment? I’m trying to understand the extent to which potential employment benefits are welcomed by communities with data center development.

This is a hot topic right now. And it’s a complicated topic and an issue that’s evolving – technology is evolving. But what we do find is engagement from the trades is a huge benefit to these projects when they come to a community because we are the community. We have operated in Wisconsin for 130 years. Our partnership with our building trades unions is often viewed by local stakeholders as the first step of building trust, frankly; they know that when we’re on a project, it’s their neighbors getting good jobs and their kids being able to perhaps train in their own backyard. And local officials know our track record. We’re accountable to stakeholders.

We are a valuable player when we are engaged and involved in these sting decisions.

When do you get engaged and to what extent?

Everyone operates differently but we often get engaged pretty early on because, obviously, our workforce is necessary to build the project. They need the manpower, they need to talk to us early on about what pipeline we have for the work. We need to talk about build-out expectations and timelines and apprenticeship recruitment, so we’re involved early on. We’ve had notable partnerships, like Microsoft in southeast Wisconsin. They’re now the single largest taxpayer in Racine County. That project is now looking to expand.

When we are involved early on, it really shows what can happen. And there are incredible stories coming out of that job site every day about what that work has meant for our union members.

To what extent are some of these communities taking in the labor piece when it comes to data centers?

I think that’s a challenging question to answer because it varies on the individual person, on what their priority is as a member of a community. What they know, what they prioritize.

Across the board, again, we’re a known entity. We are not an external player; we live in these communities and often have training centers in them. They know the value that comes from our workers and the careers we provide.

I don’t think I’ve seen anyone who says that is a bad thing. But I do think there are other factors people are weighing when they’re considering these projects and they’re incredibly personal.

How do you reckon with the personal nature of this issue, given the employment of your members is also at stake? How do you grapple with that?

Well, look, we respect, over anything else, local decision-making. That’s how this should work.

We’re not here to push through something that is not embraced by communities. We are there to answer questions and good actors and provide information about our workforce, what it can mean. But these are decisions individual communities need to make together.

What sorts of communities are welcoming these projects, from your perspective?

That’s another challenging question because I think we only have a few to go off of here.

I would say more information earlier on the better. That’s true in any case, but especially with this. For us, when we go about our day-to-day activities, that is how our most successful projects work. Good communication. Time to think things through. It is very early days, so we have some great success stories we can point to but definitely more to come.

The number of data centers opposed in Republican-voting areas has risen 330% over the past six months.

It’s probably an exaggeration to say that there are more alligators than people in Colleton County, South Carolina, but it’s close. A rural swath of the Lowcountry that went for Trump by almost 20%, the “alligator alley” is nearly 10% coastal marshes and wetlands, and is home to one of the largest undeveloped watersheds in the nation. Only 38,600 people — about the population of New York’s Kew Gardens neighborhood — call the county home.

Colleton County could soon have a new landmark, though: South Carolina’s first gigawatt data center project, proposed by Eagle Rock Partners.

That’s if it overcomes mounting local opposition, however. Although the White House has drummed up data centers as the key to beating China in the race for AI dominance, Heatmap Pro data indicate that a backlash is growing from deep within President Donald Trump’s strongholds in rural America.

According to Heatmap Pro data, there are 129 embattled data centers located in Republican-voting areas. The vast majority of these counties are rural; just six occurred in counties with more than 1,000 people per square mile. That’s compared with 93 projects opposed in Democratic areas, which are much more evenly distributed across rural and more urban areas.

Most of this opposition is fairly recent. Six months ago, only 28 data centers proposed in low-density, Trump-friendly countries faced community opposition. In the past six months, that number has jumped by 95 projects. Heatmap’s data “shows there is a split, especially if you look at where data centers have been opposed over the past six months or so,” says Charlie Clynes, a data analyst with Heatmap Pro. “Most of the data centers facing new fights are in Republican places that are relatively sparsely populated, and so you’re seeing more conflict there than in Democratic areas, especially in Democratic areas that are sparsely populated.”

All in all, the number of data centers that have faced opposition in Republican areas has risen 330% over the past six months.

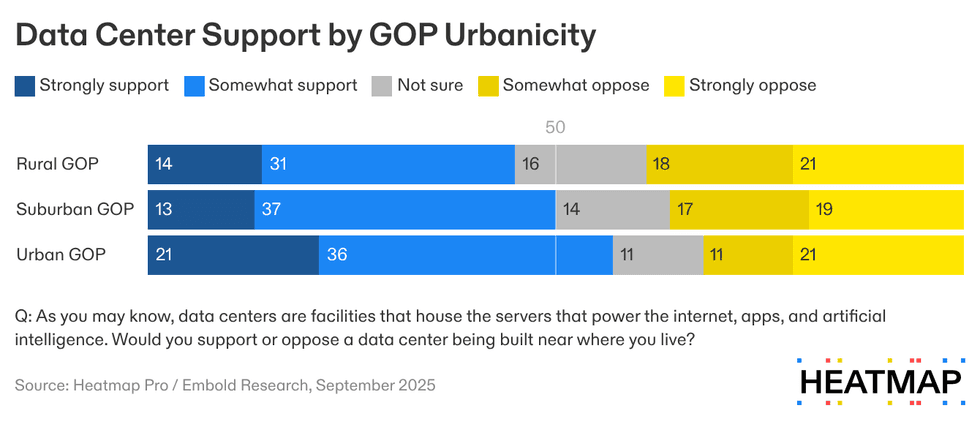

Our polling reflects the breakdown in the GOP: Rural Republicans exhibit greater resistance to hypothetical data center projects in their communities than urban Republicans: only 45% of GOP voters in rural areas support data centers being built nearby, compared with nearly 60% of urban Republicans.

Such a pattern recently played out in Livingston County, Michigan, a farming area that went 61% for President Donald Trump, and “is known for being friendly to businesses.” Like Colleton County, the Michigan county has low population density; last fall, hundreds of the residents of Howell Township attended public meetings to oppose Meta’s proposed 1,000-acre, $1 billion AI training data center in their community. Ultimately, the uprising was successful, and the developer withdrew the Livingston County project.

Across the five case studies I looked at today for The Fight — in addition to Colleton and Livingston Counties, Carson County, Texas; Tucker County, West Virginia; and Columbia County, Georgia, are three other red, rural examples of communities that opposed data centers, albeit without success — opposition tended to be rooted in concerns about water consumption, noise pollution, and environmental degradation. Returning to South Carolina for a moment: One of the two Colleton residents suing the county for its data center-friendly zoning ordinance wrote in a press release that he is doing so because “we cannot allow” a data center “to threaten our star-filled night skies, natural quiet, and enjoyment of landscapes with light, water, and noise pollution.” (In general, our polling has found that people who strongly oppose clean energy are also most likely to oppose data centers.)

Rural Republicans’ recent turn on data centers is significant. Of 222 data centers that have faced or are currently facing opposition, the majority — 55% —are located in red low-population-density areas. Developers take note: Contrary to their sleepy outside appearances, counties like South Carolina’s alligator alley clearly have teeth.