This article is exclusively

for Heatmap Plus subscribers.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

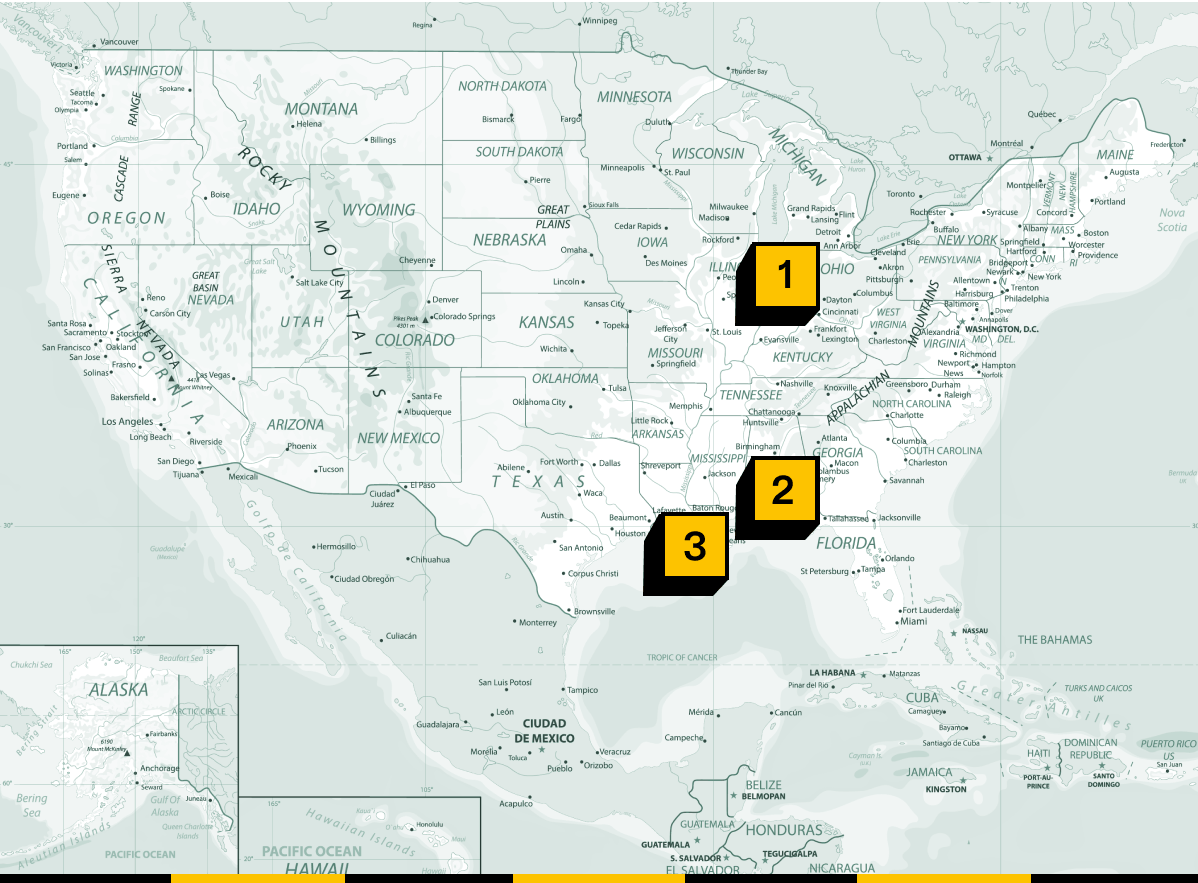

1. Marion County, Indiana — State legislators made a U-turn this week in Indiana.

2. Baldwin County, Alabama — Alabamians are fighting a solar project they say was dropped into their laps without adequate warning.

3. Orleans Parish, Louisiana — The Crescent City has closed its doors to data centers, at least until next year.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

The proportion of voters who strongly oppose development grew by nearly 50%.

During his State of the Union address Tuesday night, President Donald Trump attempted to stanch the public’s bleeding support for building the data centers his administration says are necessary to beat China in the artificial intelligence race. With “many Americans” now “concerned that energy demand from AI data centers could unfairly drive up their electricity bills,” Trump said, he pledged to make major tech companies pay for new power plants to supply electricity to data centers.

New polling from energy intelligence platform Heatmap Pro shows just how dramatically and swiftly American voters are turning against data centers.

Earlier this month, the survey, conducted by Embold Research, reached out to 2,091 registered voters across the country, explaining that “data centers are facilities that house the servers that power the internet, apps, and artificial intelligence” and asking them, “Would you support or oppose a data center being built near where you live?” Just 28% said they would support or strongly support such a facility in their neighborhood, while 52% said they would oppose or strongly oppose it. That’s a net support of -24%.

When Heatmap Pro asked a national sample of voters the same question last fall, net support came out to +2%, with 44% in support and 42% opposed.

The steep drop highlights a phenomenon Heatmap’s Jael Holzman described last fall — that data centers are "swallowing American politics,” as she put it, uniting conservation-minded factions of the left with anti-renewables activists on the right in opposing a common enemy.

The results of this latest Heatmap Pro poll aren’t an outlier, either. Poll after poll shows surging public antipathy toward data centers as populists at both ends of the political spectrum stoke outrage over rising electricity prices and tech giants struggle to coalesce around a single explanation of their impacts on the grid.

“The hyperscalers have fumbled the comms game here,” Emmet Penney, an energy researcher and senior fellow at the right-leaning Foundation for American Innovation, told me.

A historian of the nuclear power sector, Penney sees parallels between the grassroots pushback to data centers and the 20th century movement to stymie construction of atomic power stations across the Western world. In both cases, opponents fixated on and popularized environmental criticisms that were ultimately deemed minor relative to the benefits of the technology — production of radioactive waste in the case of nuclear plants, and as seems increasingly clear, water usage in the case of data centers.

Likewise, opponents to nuclear power saw urgent efforts to build out the technology in the face of Cold War competition with the Soviet Union as more reason for skepticism about safety. Ditto the current rhetoric on China.

Penney said that both data centers and nuclear power stoke a “fear of bigness.”

“Data centers represent a loss of control over everyday life because artificial intelligence means change,” he said. “The same is true about nuclear,” which reached its peak of expansion right as electric appliances such as dishwashers and washing machines were revolutionizing domestic life in American households.

One of the more fascinating findings of the Heatmap Pro poll is a stark urban-rural divide within the Republican Party. Net support for data centers among GOP voters who live in suburbs or cities came out to -8%. Opposition among rural Republicans was twice as deep, at -20%. While rural Democrats and independents showed more skepticism of data centers than their urbanite fellow partisans, the gap was far smaller.

That could represent a challenge for the Trump administration.

“People in the city are used to a certain level of dynamism baked into their lives just by sheer population density,” Penney said. “If you’re in a rural place, any change stands out.”

Senator Bernie Sanders, the democratic socialist from Vermont, has championed legislation to place a temporary ban on new data centers. Such a move would not be without precedent; Ireland, transformed by tax-haven policies over the past two decades into a hub for Silicon Valley’s giants, only just ended its de facto three-year moratorium on hooking up data centers to the grid.

Senator Josh Hawley, the Missouri Republican firebrand, proposed his own bill that would force data centers off the grid by requiring the complexes to build their own power plants, much as Trump is now promoting.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, you have Republicans such as Mississippi Governor Tate Reeves, who on Tuesday compared halting construction of data centers to “civilizational suicide.”

“I am tempted to sit back and let other states fritter away the generational chance to build. To laugh at their short-sightedness,” he wrote in a post on X. “But the best path for all of us would be to see America dominate, because our foes are not like us. They don’t believe in order, except brutal order under their heels. They don’t believe in prosperity, except for that gained through fraud and plunder. They don’t think or act in a way I can respect as an American.”

Then you have the actual hyperscalers taking opposite tacks. Amazon Web Services, for example, is playing offense, promoting research that shows its data centers are not increasing electricity rates. Claude-maker Anthropic, meanwhile, issued a de facto mea culpa, pledging earlier this month to offset all its electricity use.

Amid that scattershot messaging, the critical rhetoric appears to be striking its targets. Whether Trump’s efforts to curb data centers’ impact on the grid or Reeves’ stirring call to patriotic sacrifice can reverse cratering support for the buildout remains to be seen. The clock is ticking. There are just 36 weeks until the midterm Election Day.

NineDot Energy’s nine-fiigure bet on New York City is a huge sign from the marketplace.

Battery storage is moving full steam ahead in the Big Apple under new Mayor Zohran Mamdani.

NineDot Energy, the city’s largest battery storage developer, just raised more than $430 million in debt financing for 28 projects across the metro area, bringing the company’s overall project pipeline to more than 60 battery storage facilities across every borough except Manhattan. It’s a huge sign from the marketplace that investors remain confident the flashpoints in recent years over individual battery projects in New York City may fail to halt development overall. In an interview with me on Tuesday, NineDot CEO David Arfin said as much. “The last administration, the Adams administration, was very supportive of the transition to clean energy. We expect the Mamdani administration to be similar.”

It’s a big deal given that a year ago, the Moss Landing battery fire in California sparked a wave of fresh battery restrictions at the local level. We’ve been able to track at least seven battery storage fights in the boroughs so far, but we wouldn’t be surprised if the number was even higher. In other words, risk remains evident all over the place.

Asked where the fears over battery storage are heading, Arfin said it's “really hard to tell.”

“As we create more facts on the ground and have more operating batteries in New York, people will gain confidence or have less fear over how these systems operate and the positive nature of them,” he told me. “Infrastructure projects will introduce concern and reasonably so – people should know what’s going on there, what has been done to protect public safety. We share that concern. So I think the future is very bright for being able to build the cleaner infrastructure of the future, but it's not a straightforward path.”

In terms of new policy threats for development, local lawmakers are trying to create new setback requirements and bond rules. Sam Pirozzolo, a Staten Island area assemblyman, has been one of the local politicians most vocally opposed to battery storage without new regulations in place, citing how close projects can be to residences, because it's all happening in a city.

“If I was the CEO of NineDot I would probably be doing the same thing they’re doing now, and that is making sure my company is profitable,” Pirozzolo told me, explaining that in private conversations with the company, he’s made it clear his stance is that Staten Islanders “take the liability and no profit – you’re going to give money to the city of New York but not Staten Island.”

But onlookers also view the NineDot debt financing as a vote of confidence and believe the Mamdani administration may be better able to tackle the various little bouts of hysterics happening today over battery storage. Former mayor Eric Adams did have the City of Yes policy, which allowed for streamlined permitting. However, he didn’t use his pulpit to assuage battery fears. The hope is that the new mayor will use his ample charisma to deftly dispatch these flares.

“I’d be shocked if the administration wasn’t supportive,” said Jonathan Cohen, policy director for NY SEIA, stating Mamdani “has proven to be one of the most effective messengers in New York City politics in a long time and I think his success shows that for at least the majority of folks who turned out in the election, he is a trusted voice. It is an exercise that he has the tools to make this argument.”

City Hall couldn’t be reached for comment on this story. But it’s worth noting the likeliest pathway to any fresh action will come from the city council, then upwards. Hearings on potential legislation around battery storage siting only began late last year. In those hearings, it appears policymakers are erring on the side of safety instead of blanket restrictions.

The week’s most notable updates on conflicts around renewable energy and data centers.

1. Wasco County, Oregon – They used to fight the Rajneeshees, and now they’re fighting a solar farm.

2. Worcester County, Maryland – The legal fight over the primary Maryland offshore wind project just turned in an incredibly ugly direction for offshore projects generally.

3. Manitowoc County, Wisconsin – Towns are starting to pressure counties to ban data centers, galvanizing support for wider moratoria in a fashion similar to what we’ve seen with solar and wind power.

4. Pinal County, Arizona – This county’s commission rejected a 8,122-acre solar farm unanimously this week, only months after the same officials approved multiple data centers.

.